Psychological Well-Being of Young Athletes with Physical Disabilities: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Elegibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategies

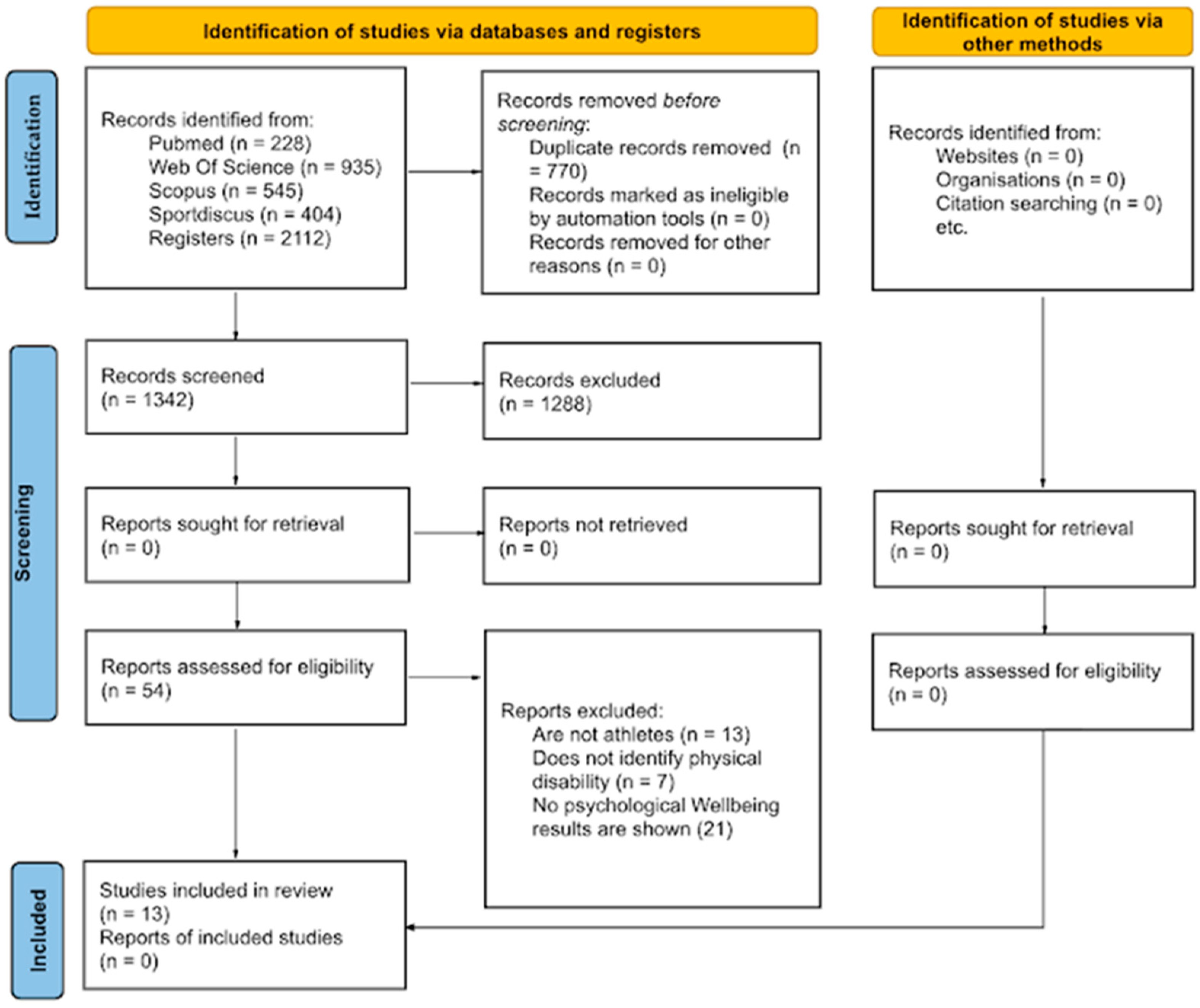

2.4. Section Process

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Items

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Search Process

3.2. Data Extraction and Synthesis

| Author/Year | Objective | Participants, Age Mean, and Sport Modality | Specific Factors of the PWB | Other Factors | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goraczko et al., (2021) [31] | Analyzing self-efficacy and quality of life in athletes with physical disabilities | Athletes with physical disabilities Age mean: 39.5 (n = 16) Not specified | Psychological dimension of QOL | General Self-Efficacy Scale | Athletes who practice more sports have a higher PWB |

| Calheiros et al., (2020) [24] | To analyze the relationship between QoL and lifestyle in athletes with physical disabilities | Athletes with physical disabilities (n = 150) Age mean: 35.07 ± 9.45 Wheelchair Handball | Psychological dimension of VC | Not applicable | The greater the sport practice, the greater the PWB |

| Campbell, (1995) [19] | To analyze the differences in PWB in athletes with congenital and acquired physical disabilities | Athletes with congenital disability (n = 50) Athletes with an acquired disability (n = 43) Age mean: 25.9 (>17 years) Wheelchair sports | Environmental dominance (2) | Mental strength Trait anxiety Self-esteem | Athletes with acquired disability show higher PWB, have higher levels of mastery. |

| Campbell and Jones, (1994) [32] | To analyze the PWB in athletes and non-athletes and to analyze according to the level of according to the level of competition | Athletes with disabilities (n = 72) Non-athletes with disabilities (n = 29) Age mean: 32 (>17 years) Wheelchair sports | Environmental dominance (2) | Mental strength Trait anxiety Self-esteem | Sportsmen have higher mastery than non-athletes. The higher the level of competition, the higher the mastery |

| Nemček et al., (2020) [33] | To analyze the subjective perception of QoL in subjects with physical disabilities, athletes and non-athletes | Competitive athletes (n = 26) Recreational athletes (n = 45) Non-sportsmen (n = 59) Age mean: 24.4 ± 1.9 Boccia | Psychological dimension | Subjective quality of life | There is no difference in PWB between athletes and non-athletes |

| Jooste and Kubayi (2018) [34] | To analyze the levels of PWB shown by athletes with physical disability in Wheelchair Basketball | Athletes with disability (n = 16) Age mean: 32.13 ± 6.62 Wheelchair Basketball | (1) Autonomy (2) Mastery of the environment (3) Personal growth (4) Positive relationships (5) Life purpose (6) Self-acceptance | Subjective Vitality | Athletes show positive PWB values. The most valued dimensions: Personal growth (3) and Acceptance (6). |

| Yazicioglu et al., (2012) [26] | To compare the levels of QoL and Satisfaction with life between athletes and non-athletes with physical disabilities | Athletes (n = 30) Non-athletes (n = 30) Age: >18 years Not specified | Psychological dimension of QOL | Satisfaction with life | Athletes have higher levels of PWB |

| Medina et al., (2013) [35] | To analyze the relationship between PWB and type of sport practice in people with physical disability of neurological origin | Competitive sport group (n = 40) Age mean: 37.6 ± 15.6 Wheelchair Basketball, Tennis, Athletics and Boccia | Self-control/Mastery of the environment (2) | Not applicable | Athletes present higher levels of PWB and lower levels of anxiety and depression. |

| Yazici Gulay et al., (2022) [26] | To analyze the QOL of athletes and non-athletes with physical disabilities | Non-athletes (n = 19) Athletes: (n = 17) Boccia (n = 9) Wheelchair Basketball (n = 8) Age mean: 31.57 ± 10.15 | Psychological dimension of QOL | Mobility Index Functional Independence Measurement Trunk impairment scale | Athletes have a higher psychological domain than non-athletes, and among sports, Boccia players have higher levels than wheelchair basketball players. |

| Zelenka et al., (2017) [22] | Analizar el efecto del Rugby en silla de ruedas sobre la CV de personas con lesión medular | Non-sportsmen (n = 16) Athletes (n = 20) Age mean: 32.5 ± 8.46 Wheelchair rugby | Psychological dimension of QoL | Not applicable | No difference between athletes and non-athletes |

| Trujillo Santana et al., (2022) [36] | Describe the PWB of high-performance athletes with and without disabilities | Athletes without disabilities (n = 31) Athletes with disability (n = 34) Age mean: 19.71 ± 1.96 Not specified | (2) Mastery of the environment Social links Projects Acceptance | Mental strength Subjective Vitality | Athletes show positive PWB values |

| Ciampolini et al., (2018) [37] | To compare the perception of QOL of Boccia, athletics, and wheelchair tennis athletes | Boccia (n = 41) Athletics (n = 14) Wheelchair Tennis (n = 31) Age mean: 39.35 ± 11.57 | Psychological dimension of VC | Not applicable | Athletes have higher PWB than Boccia or wheelchair tennis players. |

| Nowak et al., (2022) [25] | To analyze the relationship between QoL and health satisfaction with the sport level of athletes with physical disabilities | Amateur athletes (n = 126) Professional athletes (n = 66) Age mean: 34.48 ± 8.79 Wheelchair basketball Wheelchair rugby Rowing Individual sports | Psychological dimension of QOL | Not applicable | Amateur athletes have higher CVs and satisfaction than competitive athletes. Among sport types, wheelchair basketball athletes have higher satisfaction and CV than rugby and rowing players. |

3.3. Measurement Tools and Specific Dimensions Used to Measure PWB

| PWB Factors Analyzed | PWB Tool (Items and Reliability) | Other Factors Analyzed (Those That Are Related to PWB) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy (1) | Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWBS) [38] | Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS) [39] | [34] |

| Mastery of the environment (2) | |||

| Personal growth (3) | |||

| Social bonds (4) | |||

| Projects (5) | |||

| Acceptance (6) | |||

| Mastery of the environment (2) | Psychological Wellbeing Scale BIEPS [40] | Mental Toughness Inventory (MTI) [41] | [36] |

| Acceptance (6) | |||

| Social bonds (4) | |||

| Projects (5) | |||

| Mastery of the environment/self-control (2) | Psychological well-being index (PWBI) [42] | Not applicable | [35] |

| Mastery of the environment (2) | Mastery [43] | Profile of Mood States (POMS) [44] | [19,32] |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [45] | |||

| Self-Esteem Scale [46] | |||

| Psychological dimension (CVd2) | World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQoL-BREF) [47] | Not applicable | [22,24,25,38] |

| Satisfaction with life [48] | [26] | ||

| Subjective quality of life [49] | [33] | ||

| Self-efficacy [50] | [31] | ||

| World Health Organization Quality of Life Disability (WHOQOL-DIS) [51] | Rivermead Mobility Index (RMI) [52] Measurement of Functional Independence (MIF) [53] Scale trunk impairment (TIS) [54] | [26] |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Puce, L.; Okwen, P.M.; Yuh, M.N.; Akah Ndum Okwen, G.; Pambe Miong, R.H.; Kong, J.D.; Bragazzi, N.L. Well-being and quality of life in people with disabilities practicing sports, athletes with disabilities, and para-athletes: Insights from a critical review of the literature. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1071656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Children and Youth with Disabilities, Fact Sheet 2021; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/es/comunicados-prensa/casi-240-millones-ninos-con-discapacidad-mundo-segun-analisis-estadistico (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Fernández-López, J.A.; Fernández-Fidalgo, M.; Geoffrey, R.; Stucki, G.; Cieza, A. Funcionamiento y discapacidad: La Clasificación Internacional del Funcionamiento (CIF). Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2009, 83, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Han, A.; Nguyen, M.C. The contribution of physical and social activity participation to social support and happiness among people with physical disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 14, 100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olasagasti-Ibargoien, J.; Castañeda-Babarro, A.; León-Guereño, P.; Uria-Olaizola, N. Barriers to Physical Activity for Women with Physical Disabilities: A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán Hernández, R.; Anderson Quiñonez, J.; Arenas, J.; Urrea, Á.M.; Barbosa-Granados, S.; Aguirre Loaiza, H. Características Psicológicas en Deportistas con Discapacidad Física Psychological (Characteristics in athletes with physical disability). Retos 2021, 40, 351–358. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, R.; Miller, E.K.; Kraus, E.; Fredericson, M. Impact of adaptive sports participation on quality of life. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2019, 27, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Pay, A. Análisis de la producción científica sobre el tenis en silla de ruedas. Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. Act. Física Deporte 2019, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero-Duque, M.F. Concepciones sobre la motivación para la práctica de actividades físico-deportivas en personas con discapacidad física. Rev. Científica Espec. Cienc. Cult. Física Deporte 2022, 19, 156–178. [Google Scholar]

- Jaarsma, E.A.; Dijkstra, P.U.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Dekker, R. Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Foster, C.; Lai, B.; McBride, C.B.; Ng, K.; Pratt, M.; Shirazipour, C.H.; Smith, B.; Vásquez, P.M.; et al. Participation of people living with disabilities in physical activity: A global perspective. Lancet 2021, 398, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, C.; Barton, J.; Orbell, S.; Andrews, L. Psychological benefits of outdoor physical activity in natural versus urban environments: A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2022, 14, 1037–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaenes, J.C.; Alarcón, D.; Trujillo, M.; Méndez-Sánchez, M.d.P.; León-Guereño, P.; Wilczyńska, D. A Moderated Mediation Model of Wellbeing and Competitive Anxiety in Male Marathon Runners. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 800024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, C. Well-being in competitive sports-The feel-good factor? A review of conceptual considerations of well-being. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2011, 4, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwueze, F.C.; Agbaje, O.S.; Umoke, P.C.I.; Ozoemena, E.L. Relationship Between Physical Activity Levels and Psychological Well-Being Among Male University Students in South East, Nigeria: A Cross-Sectional Study. Am. J. Mens. Health 2021, 15, 15579883211008337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Boylan, J.M.; Kirsch, J.A. Eudaimonic and hedonic well-being: An integrative perspective with linkages to sociodemographic factors and health. In Measuring Well-Being: Interdisciplinary Perspectives from the Social Sciences and the Humanities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 92–135. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351056903_Eudaimonic_and_Hedonic_Well-Being_An_Integrative_Perspective_with_Linkages_to_Sociodemographic_Factors_and_HealthAn_Integrative_Perspective_with_Linkages_to_Sociodemographic_Factors_and_Health (accessed on 3 March 2014).

- Campbell, E. Psychological well-being of participants in wheelchair sports: Comparison of individuals with congenital and acquired disabilities. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1995, 81, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretti, G.; Mirandola, D.; Sgambati, E.; Manetti, M.; Marini, M. Survey on Psychological Well-Being and Quality of Life in Visually Impaired Individuals: Dancesport vs. Other Sound Input-Based Sports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, A.; Iuliano, E.; Aquino, G.; Fiorilli, G.; Battaglia, C.; Giombini, A.; Calcagno, G. Psychological well-being and social participation assessment in visually impaired subjects playing Torball: A controlled study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenka, T.; Kudlácek, M.; Wittmannová, J. Quality of life of wheelchair rugby players. Eur. J. Adapt. Phys. Act. 2017, 10, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles Pérez, M.F. Evaluación del uso de Redes Sociales y su Influencia en el Bienestar Psicológico en Población Universitaria; Universidad de Extremadura: Badajoz, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=290129 (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Calheiros, D.d.S.; Cavalcante Neto, J.L.; de Melo, F.A.P.; Munster, M.d.A.v. The Association between Quality of Life and Lifestyle of Wheelchair Handball Athletes. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2020, 32, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.A.; Kolbowicz, M.; Sochacki, A.; Król, P.; Nowak, L.; Kotarska, K. The relationships between the performance level and type of sport and the quality of life and health satisfaction of the disabled who practice sport. Acta Kinesiol. 2022, 16, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazicioglu, K.; Yavuz, F.; Goktepe, A.S.; Tan, A.K. Influence of adapted sports on quality of life and life satisfaction in sport participants and non-sport participants with physical disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2012, 5, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, D.R.; Malone, L.A. Quality of life and psychological affect related to sport participation in children and youth athletes with physical disabilities: A parent and athlete perspective. Disabil. Health J. 2016, 9, 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Higgins, J.P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, C.; Glanville, J.; Briscoe, S.; Littlewood, A.; Marshall, C.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Noel-Storr, A.; Rader, T.; Shokraneh, F.; Thomas, J.; et al. Searching for and Selecting Studies; Wiley Online Library: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goraczko, A.; Zurek, A.; Lachowicz, M.; Kujawa, K.; Zurek, G. Is self-efficacy related to the quality of life in elite athletes after spinal cord injury? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, E.; Jones, G. Psychological Well-Being in Wheelchair Sport Participants and Nonparticipants. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 1994, 11, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemček, D.; Wittmannová, J.; Javanainen-Levonen, T.; Lubkowska, W. Subjective Perception of Life Quality Among Men with Physical Disabilities with Different Sport Participation Level. Acta Fac. Educ. Phys. Univ. Comen. 2020, 60, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooste, J.; Kubayi, A.N. Perceived coach leadership style and psychological well-being among South African national male wheelchair basketball players. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.; Chamarro, A.; Parrado, E. Efectividad de la aplicación de ultrasonido terapéutico y ejercicio de estiramiento a músculos isquiotibiales en niños con parálisis cerebral tipo diparesia espástica leve. Rehabilitacion 2013, 47, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Santana, T.; Maestre-Baidez, M.; Preciado-Gutierrez, K.Y.; Ortin-Montero, F.J.; López-Fajardo, A.D.; López-Morales, J.L. Bienestar psicológico, fortalezas y vitalidad subjetiva en deportistas con discapacidad. Retos 2022, 45, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampolini, V.; Pinto, M.G.; De Sousa, G.R.; Silva, D.A.S.; Galatti, L.R. Do athletes with physical disabilities perceive their quality of life similarly when involved in different Paralympic Sports? Mot. Rev. Educ. Fis. 2018, 24, e101873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.; Keyes, M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostic, T.J.; Rubio, D.M.; Hood, M. A validation of the subjective vitality scale using structural equation modeling. Soc. Indic. Res. 2000, 52, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casullo, M.M.; Solano, A.C. Evaluación del bienestar psicológico en estudiantes adolescentes argentinos. Rev. Psicol. 2000, 18, 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gucciardi, D.F.; Hanton, S.; Gordon, S.; Mallett, C.J.; Temby, P. The Concept of Mental Toughness: Tests of Dimensionality, Nomological Network, and Traitness. J. Personal. 2015, 83, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, X.; Gutiérrez, F.; Wiklund, I.; Alonso, J. Validity and reliability of the Spanish Version of the Psychological General Well-Being Index. Qual. Life Res. 1996, 5, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Schooler, C. The Structure of Coping. J. Health Soc. Behavior. 1978, 19, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, D.M.; Lorr, M.; Droppleman, L.F. Manual Profile of Mood States; Educational and Industrial Testing Service: San Diego, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R. Manual for the State’Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton Univer Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Development of the World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannotti, M.; Pringuey, D. A method for quality of life assessment in psychiatry: The S-QUA-L-A (Subjective QUAlity of Life Analysis). Qual. Live News Letter. 1992, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherer, M.; Maddux, J.E.; Mercandante, B.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Jacobs, B.; Rogers, R.W. The self-efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychol. Rep. 1982, 51, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M.J.; Green, A.M. Development of the WHOQOL disabilities module. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collen, F.M.; Wade, D.T.; Robb, G.F.; Bradshaw, C.M. The Rivermead mobility index: A further development of the Rivermead motor assessment. Int. Disabil. Stud. 1991, 13, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küçükdeveci, A.; Yavuzer, G.; Elhan, A.; Sonel, B.; Tennant, A. Adaptation of the Functional Independence Measure for use in Turkey. Clin. Rehabil. 2001, 15, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyden, G.; Nuyens, G.; Nieuwboer, A.; Van Asch, P.; Ketelaer, P.; De Weerdt, W. Reliability and validity of trunk assessment for people with multiple sclerosis. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dierendonck, D.; Lam, H. Interventions to enhance eudaemonic psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review with Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-being. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2022, 15, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román Ross, M.I.; Jorge, E. Dimensiones del Bienestar Psicológico en usuarios que asisten a un Taller de Musicoterapia de un Hospital Polivalente de la ciudad de Córdoba. Aproximaciones desde la Psicología Positiva. Rev. Electrónica Psicol. Iztacala 2021, 24, 347–372. [Google Scholar]

- Casullo, M.; Solano, C.; Cruz, M.; González, R.; Maganto, C.; Martín, M.; Pérez, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Sánchez, L.; y Torres, G.; et al. Evaluación del Bienestar Psicológico en Iberoamérica, 1st ed.; Paidós, Ed.; Cuadernos de Evaluación Psicológica: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 27–65. [Google Scholar]

- Figuerola-Escoto, R.P.; Luna, D.; Lezana-Fernández, M.A.; Meneses-González, F. Psychometric properties of the psychological well-being scale for adults (BIEPS-A) in a Mexican sample. Rev. CES Psicol. 2021, 14, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rojas, S.M.; Ruiz-Roa, S.L. Psychological well-being in nurses performing renal replacement therapy in times of COVID-19 pandemic. Enferm. Nefrol. 2022, 25, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, S.; Malhotra, R. The filial piety paradox: Receiving social support from children can be negatively associated with quality of life. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 303, 114996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giolo-Melo, C.; Pacheco, R.T.B. Physical Activity, Public Policy, Health Promotion, Sociability and Leisure: A Study on Gymnastics Groups in a Brazilian City Hall. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.S.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, H.X.; Wang, H.F.; Yang, Y.H.; Gao, Y.; Fu, C.W.; Chen, G.; Lu, J. Preliminary validation study of the WHO quality of life (WHOQOL) scales for people with spinal cord injury in Mainland China. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2022, 45, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, C.M.; Dzewaltowski, D.A.; French, R. Self-efficacy and psychological well-being of wheelchair tennis participants and wheelchair nontennis participants. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 1990, 7, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.A. Physical Disabilities: A Psychological Approach; Harper & Row Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mira, T.; Costa, A.M.; Jacinto, M.; Diz, S.; Monteiro, D.; Rodrigues, F.; Matos, R.; Antunes, R. Well-Being, Resilience and Social Support of Athletes with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baretta, D.; Greco, A.; Steca, P. Understanding performance in risky sport: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and sensation seeking in competitive freediving. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 117, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, D.R.; Martin, J.J. The relationships among sport self-perceptions and social well-being in athletes with physical disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2014, 7, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, D.R.; Martin, J.J. Athletic identity, affect, and peer relations in youth athletes with physical disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2010, 3, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrajo, E.; Azanza, G.; Urquijo, I. An adaptation of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire for the sports environment. Rev. Psicol. Deporte/J. Sport Psychol. 2022, 31, 176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Jiménez, M.T.; Saiz Galdós, J.; Montero Arredondo, M.T.; Navarro Bayón, D. Adaptación de la Escala Multidimensional de Apoyo Social Percibido en población con trastorno mental grave. Rev. Asoc. Española Neuropsiquiatr. 2017, 37, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrángolo, G.; Simkin, H.; Azzollini, S.C. Evidencia de validez de la Escala Multidimensional de Apoyo Social Percibido (EMASP) en población adulta Argentina. Rev. CES Psicol. 2022, 15, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrón Vallejo, E. Variables Psicológicas Relevantes en el Deporte Adaptado; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2017; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/48178 (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- León-Guereño, P.; Tapia-Serrano, M.A.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A. The relationship of recreational runners’ motivation and resilience levels to the incidence of injury: A mediation model. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogles, B.M.; Masters, K. A typology of marathon runners based on cluster analysis of motivations Spirituality and Health View project. J. Sport Behav. 2003, 26, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- León-Pérez, J.M.; Antino, M.; León-Rubio, J.M. Adaptation of the short version of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-12) into Spanish/Adaptación al español de la versión reducida del Cuestionario de Capital Psicológico (PCQ-12). Rev. Psicol. Soc. 2017, 32, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, F.; Martin, J. Gritty, hardy, resilient, and socially supported: A replication study. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 13, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.H.; Jang, C.Y.; O’Sullivan, D.; Oh, H. Applications of psychological skills training for Paralympic table tennis athletes. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2018, 14, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, A.; Reza, S.H.; Ahmadi, F.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Safari, M.A.; Keshazarz, M.H.; Ramsbottom, R. Investigating the Relationship between Big Five Personality Traits and Sports Performance among Disabled Athletes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8072824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Articles Found | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | Wos | Scopus | Sportdiscus | |

| 1-“Psychological well-being” OR “Psychological well-being” AND sport AND disabil * | 6 | 554 | 106 | 49 |

| 2-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND state of mind | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 3-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND anxiety | 21 | 31 | 82 | 32 |

| 4-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND self-esteem | 19 | 32 | 0 | 20 |

| 5-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND environment | 40 | 83 | 186 | 74 |

| 6-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND self-perception | 5 | 14 | 28 | 14 |

| 7-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND quality of life | 110 | 170 | 7 | 170 |

| 8-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND social relations * | 4 | 8 | 17 | 10 |

| 9-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND psychological disorders | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 10-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND depression | 22 | 42 | 114 | 33 |

| 11-Physic * AND disab * AND sport AND subjective vitality | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Total without duplicates | 1342 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zabala-Dominguez, O.; Lázaro Fernández, Y.; Rubio Florido, I.; Olasagasti-Ibargoien, J. Psychological Well-Being of Young Athletes with Physical Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090822

Zabala-Dominguez O, Lázaro Fernández Y, Rubio Florido I, Olasagasti-Ibargoien J. Psychological Well-Being of Young Athletes with Physical Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(9):822. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090822

Chicago/Turabian StyleZabala-Dominguez, Olatz, Yolanda Lázaro Fernández, Isabel Rubio Florido, and Jurgi Olasagasti-Ibargoien. 2024. "Psychological Well-Being of Young Athletes with Physical Disabilities: A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 9: 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090822

APA StyleZabala-Dominguez, O., Lázaro Fernández, Y., Rubio Florido, I., & Olasagasti-Ibargoien, J. (2024). Psychological Well-Being of Young Athletes with Physical Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090822