Meta-Analysis of Collaborative Inhibition Moderation by Gender, Membership, Culture, and Memory Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Gender

1.2. Membership

1.3. Cultural Research

1.4. Memory Monitoring Research

1.5. Existing Meta-Analyses

1.6. Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Coding of Moderator Variables

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

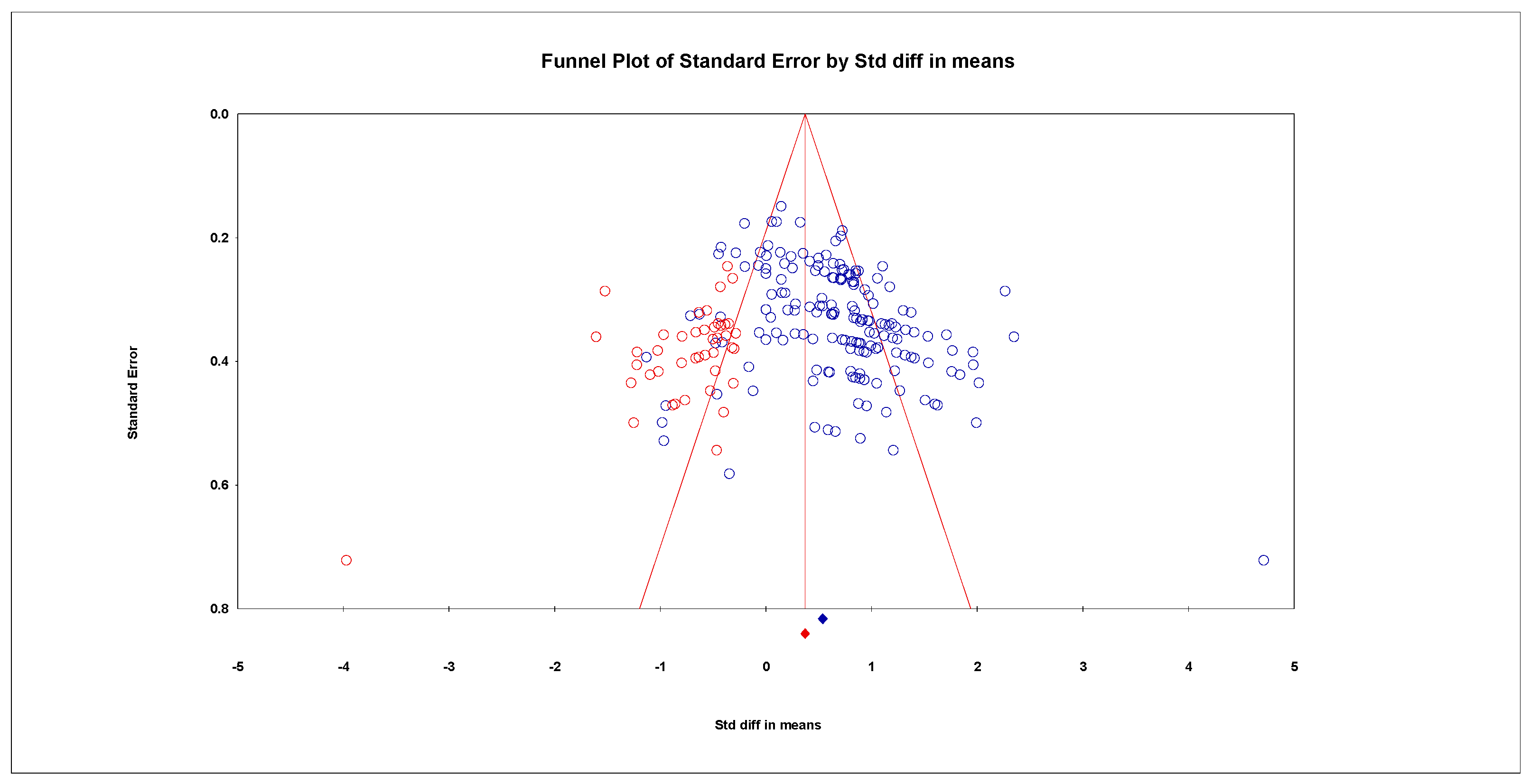

3.1. Main Pooled Results

3.2. Subgroup Analyses

- Collaborative pairing gender (n1 = 1261, n2 = 1280) had a significant moderating effect (QB = 15.08, p < 0.001), whereas opposite-sex (n1 = 228, n2 = 227) collaboration inhibition did not have a significant effect (p = 0.52). (Note: n1 represents the number of collaborative groups; n2 represents the number of nominal groups. the same below.)

- Membership (n1 = 1575, n2 = 1650) had a significant moderating effect (QB = 17.68, p < 0.001), with the highest collaboration inhibition effect observed in the strangers group (n1 = 472, n2 = 481, d = 0.75), followed by the acquaintances group (n1 = 758, n2 = 824, d = 0.45). The collaboration inhibition effect was not significant in the couple group (n1 = 148, n2 = 147, p = 0.45) or the friends group (n1 = 197, n2 = 198, p = 0.35).

- Cultural factors (n1 = 4265, n2 = 4313) had a significant moderating effect (QB = 11.53, p < 0.001), with a greater collaborative inhibition effect observed in Western culture (n1 = 4265, n2 = 4313, d = 0.76) than in Eastern culture (n1 = 2251, n2 = 2345, d = 0.47).

- Memory monitoring (n1 = 3773, n2 = 4313) had a significant moderating effect (QB = 18.47, p < 0.001). The collaborative inhibition effect was significant without the addition of memory monitoring (n1 = 3758, n2 = 3724, d = 0.66, p < 0.001), but it disappeared after the addition of memory monitoring (n1 = 507, n2 = 589, d = 0.14, p = 0.2).

3.3. Subgroup Analyses (Published Only)

- Collaborative pairing gender (n1 = 732, n2 = 729) had a significant moderating effect (QB = 12.61, p < 0.001), whereas opposite-sex (n1 = 228, n2 = 227) collaboration inhibition did not have a significant effect (p = 0.46).

- Membership (n1 = 976, n2 = 950) had a significant moderating effect (QB = 10.64, p < 0.05), with the highest collaboration inhibition effect observed in the strangers group (n1 = 645, n2 = 620, d = 0.7), followed by the acquaintances group (n1 = 159, n2 = 159, d = 0.59). The collaboration inhibition effect was not significant in the couple group (n1 = 148, n2 = 147, p = 0.45) and the friends group (n1 = 24, n2 = 24, p = 0.57).

- The moderating effect of cultural factors (n1 = 2751, n2 = 2703) was not significant (QB = 2.31, p = 0.13).

3.4. Relationship between the Year of Publication and Collaborative Inhibition

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Effects of Collaborative Inhibition

4.2. Moderating Effects of Collaborative Inhibition

4.2.1. Gender Facilitation

4.2.2. Transactive Memory System

4.3. Culture

4.4. Memory Monitoring

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Directions

4.6. The Year of Publication and Collaborative Inhibition

4.7. Innovations and Practical Significance

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meade, M.L.; Nokes, T.J.; Morrow, D.G. Expertise promotes facilitation on a collaborative memory task. Memory 2009, 17, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraiva, M.; Albuquerque, P.B.; Garrido, M.V. Collaborative inhibition effect: The role of memory task and retrieval method. Psychol. Res. 2023, 87, 2548–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weldon, M.S.; Bellinger, K.D. Collective memory: Collaborative and individual processes in remembering. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1997, 23, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whillock, S.R.; Meade, M.L.; Hutchison, K.A.; Tsosie, M.D. Collaborative inhibition in same-age and mixed-age dyads. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basden, B.H.; Basden, D.R.; Bryner, S.; Iii, R.L.T. A comparison of group and individual remembering: Does collaboration disrupt retrieval strategies? J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1997, 23, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cue, A.; Koppel, J.; Hirst, W. Silence Is Not Golden: A Case for Socially Shared Retrieval-Induced Forgetting. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Shi, J. Inhibitory process of collaborative inhibition: Assessment using an emotional stroop task. Psychol. Rep. 2020, 123, 300–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Z.; Duan, Y.; Chen, N.; Liu, W. How collaboration reduces memory errors: A meta-analysis review. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2023, 55, 1780–1792. [Google Scholar]

- Marion, S.B.; Thorley, C. A meta-analytic review of collaborative inhibition and postcollaborative memory: Testing the predictions of the retrieval strategy disruption hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B.; Williams, K.; Harkins, S. Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, M.S.; Blair, C.; Huebsch, P.D. Group remembering: Does social loafing underlie collaborative inhibition? J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2000, 26, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C. The Role of Social and Cognitive Factors in Collaborative Memory. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, J. Net effect of memory collaboration: How is collaboration affected by factors such as friendship, gender and age? Scand. J. Psychol. 2001, 42, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.B.; Keil, P.G.; Sutton, J.; Barnier, A.J.; McIlwain DJ, F. We remember, we forget: Collaborative remembering in older couples. Discourse Process. 2011, 48, 267–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, X.; Wu, J. The influence of members’ relationship on collaborative remembering. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2021, 53, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N. The Development of Collaborative Inhibition and Its Memory Monitoring. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, M.; Bäuml, K.-H.T. Joint contributions of collaborative facilitation and social contagion to the development of shared memories in social groups. Cognition 2023, 238, 105453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.H.; Jing, Y.M.; Yu, F.; Gu, R.L.; Zhou, X.Y.; Zhang, J.X.; Cai, H. Increasing individualism and decreasing collectivism? Cultural and psychological change around the globe. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 2068–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R. The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently... and Why; Simon and Schuster: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z. Developmental Characteristics of Learning Level Judgement and Its Feedback in Collaborative Memory of High School Students. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Developmental Characteristics of the Level of Judgement of the Degree of Learning in Collaborative Memory and Its Facilitatio. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; He, Y.; Shi, J. Clustering strategy in intellectually gifted children: Assessment using a collaborative recall task. Gift. Child Q. 2017, 61, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ming, W. A cross-sectional comparison of metamemory monitoring research. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 35, 1102–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, D.M. Transactive Memory: A Contemporary Analysis of the Group Mind. In Theories of Group Behavior; Mullen, B., Goethals, G.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.F.; Ouyang, H.Y.; Yu, L. The relationship between grandparenting and depression in Eastern and Western cultures: A meta-analysis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 30, 1981–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (RoB 2.0): Additional Considerations for Cross-Over Trials (20 October 2016). Available online: https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/archive-rob-2-0-cross-over-trials-2016 (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Li, Z.; Mo, L. Testing the sex facilitation hypothesis, does the gender of the audience really influence task performance? J. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 6, 1400–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Von Siemens, F. Team Production, Gender Diversity, and Male Courtship Behavior. CESifo Working Paper. 2015. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ces/ceswps/_5259.html (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Duan, H.; Yang, T.; Wang, X.; Kan, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, W. Is the creativity of lovers better? A behavioral and functional near-infrared spectroscopy hyperscanning study. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.C.; Spellman, B.A. On the Status of Inhibitory Mechanisms in Cognition: Memory Retrieval as a Model Case. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basden, B.H.; Basden, D.R.; Henry, S. Costs and benefits of collaborative remembering. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2000, 14, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-Y.; Blumen, H.M.; Congleton, A.R.; Rajaram, S. The role of group configuration in the social transmission of memory: Evidence from identical and reconfigured groups. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2014, 26, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.B.; Barnier, A.J.; Sutton, J. Shared encoding and the costs and benefits of collaborative Recall. J. Exp. Psychol.-Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2012, 39, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, O.; Andersson, J.; Rönnberg, J. Do elderly couples have a better prospective memory than other elderly people when they collaborate? Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2000, 14, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peker, M.; Tekcan A, İ. The role of familiarity among group members in collaborative inhibition and social contagion. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 40, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutchess, A.H.; Yoon, C.; Luo, T.; Feinberg, F.; Hedden, T.; Jing, Q.; Nisbett, R.E.; Park, D.C. Categorical Organization in Free Recall across Culture and Age. Gerontology 2006, 52, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Salvador, C.E. Cultural Psychology: Beyond East and West. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2024, 75, 495–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Liu, X.; Fang, G. A review of memory monitoring research. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 4, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R.R.; Einstein, G.O. Relational and item-specific information in memory. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1981, 20, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R.R. Precision in Memory Through Distinctive Processing. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, J.C.; Pigott, T.D.; Rothstein, H.R. How Many Studies Do You Need? A Primer on Statistical Power for Meta-Analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2010, 35, 215–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, N. Applied Meta-Analysis for Social Science Research; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, M. What is the minimum number of effect sizes required in meta-regression? An estimation based on statistical power and estimation precision. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 28, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trespidi, C.; Barbui, C.; Cipriani, A. Why it is important to include unpublished data in systematic reviews. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2011, 20, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dahlström, Ö.; Danielsson, H.; Emilsson, M.; Andersson, J. Does retrieval strategy disruption cause general and specific collaborative inhibition? Memory 2011, 19, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, S.J.; Rajaram, S. Exploring the relationship between retrieval disruption from collaboration and recall. Memory 2011, 19, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.R.; Pentz, C.; Reysen, M.B. The joint influence of collaboration and part-set cueing. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2014, 67, 1977–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, A.; Guo, B. Benefits and detriments of social collaborative memory in turn-taking and directed forgetting. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2023, 130, 1040–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subgroup | Heterogeneity | Dimension | k | d | 95% CI | Bilateral Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QB | df | p | Lower | Upper | z | p | ||||

| Collaborative pairing gender | 15.08 | 1 | <0.001 | |||||||

| same-sex | 40 | 0.64 | 0.45 | 0.83 | 6.65 | <0.001 | ||||

| opposite-sex | 15 | −0.11 | −0.44 | 0.22 | −0.65 | 0.52 | ||||

| Membership | 17.68 | 3 | <0.001 | |||||||

| couple | 9 | −0.19 | −0.69 | 0.31 | −0.75 | 0.45 | ||||

| friends | 8 | 0.18 | −0.20 | 0.55 | 0.93 | 0.35 | ||||

| acquaintances | 21 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.63 | 4.71 | <0.001 | ||||

| strangers | 46 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.93 | 8.06 | <0.001 | ||||

| Culture | 11.53 | 1 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Eastern culture | 90 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.60 | 6.85 | <0.001 | ||||

| Western culture | 95 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 14.90 | <0.001 | ||||

| Memory monitoring | 18.47 | 1 | <0.001 | |||||||

| no | 173 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 14.24 | <0.001 | ||||

| yes | 12 | 0.14 | −0.08 | 0.36 | 1.27 | 0.20 | ||||

| Subgroup | Heterogeneity | Dimension | k | d | 95% CI | Bilateral Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QB | df | p | Lower | Upper | z | p | ||||

| Collaborative pairing gender | 12.61 | 1 | <0.001 | |||||||

| same-sex | 24 | 0.70 | 0.40 | 1 | 4.56 | <0.001 | ||||

| opposite-sex | 15 | −0.11 | −0.44 | 0.22 | −0.65 | 0.52 | ||||

| Membership | 10.64 | 3 | <0.05 | |||||||

| couple | 9 | −0.19 | −0.69 | 0.31 | −0.75 | 0.45 | ||||

| friends | 2 | 0.22 | −0.53 | 0.97 | 0.57 | 0.57 | ||||

| acquaintances | 8 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 0.99 | 4.71 | <0.001 | ||||

| strangers | 30 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.95 | 5.5 | <0.001 | ||||

| Culture | 2.31 | 1 | 0.13 | |||||||

| Eastern culture | 42 | 0.54 | 0.28 | 0.80 | 4.01 | <0.001 | ||||

| Western culture | 93 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 14.62 | <0.001 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, X.; Zhao, B.; Tang, W.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, X. Meta-Analysis of Collaborative Inhibition Moderation by Gender, Membership, Culture, and Memory Monitoring. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090763

Luo X, Zhao B, Tang W, Xiao Q, Liu X. Meta-Analysis of Collaborative Inhibition Moderation by Gender, Membership, Culture, and Memory Monitoring. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(9):763. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090763

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Xiaochun, Boyao Zhao, Weihai Tang, Qian Xiao, and Xiping Liu. 2024. "Meta-Analysis of Collaborative Inhibition Moderation by Gender, Membership, Culture, and Memory Monitoring" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 9: 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090763

APA StyleLuo, X., Zhao, B., Tang, W., Xiao, Q., & Liu, X. (2024). Meta-Analysis of Collaborative Inhibition Moderation by Gender, Membership, Culture, and Memory Monitoring. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090763