The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Mental Health in Chinese Undergraduates: The Mediating Roles of Self-Esteem and Interpersonal Trust

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Revised Meaning in Life Questionnaire (RMLQ)

2.3.2. Kessler10 Scale

2.3.3. Revised Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)

2.3.4. Interpersonal Trust Scale (ITS)

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. The Overall Mental Health of Chinese Undergraduates

3.2. Correlation Analysis of Investigated Variables

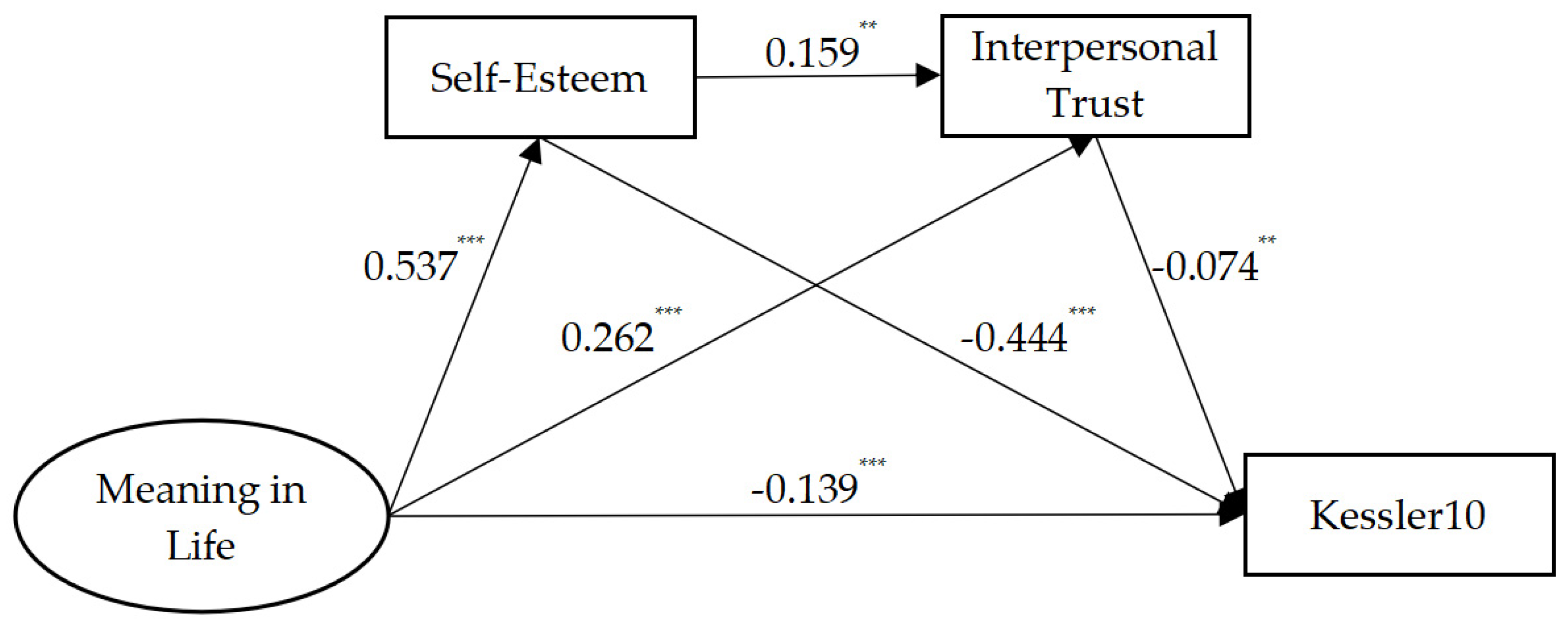

3.3. Testing the Multiple Mediating Effects

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Further Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheldon, E.; Simmonds-Buckley, M.; Bone, C.; Mascarenhas, T.; Chan, N.; Wincott, M.; Gleeson, H.; Sow, K.; Hind, D.; Barkham, M. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Mental Health Problems in University Undergraduate Students: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 287, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Oishi, S.; Kashdan, T.B. Meaning in Life across the Life Span: Levels and Correlates of Meaning in Life from Emerging Adulthood to Older Adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W. Toward a Unifying Theoretical and Practical Perspective on Well-Being and Psychosocial Adjustment. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 482–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Oishi, S.; Kesebir, S. Is a Life without Meaning Satisfying? The Moderating Role of the Search for Meaning in Satisfaction with Life Judgments. J. Posit. Psychol. 2011, 6, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.; Luciano, E.C. Self-Esteem, Narcissism, and Stressful Life Events: Testing for Selection and Socialization. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Lu, C.Y.; Shuai, M.Q.; Wenger, J.L.; Peng, C.H.; Wang, H. Meaning in Life among Chinese Undergraduate Students in the Post-Epidemic Period: A Qualitative Interview Study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1030148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth, U.; Robins, R.W.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Maes, J.; Schmitt, M. Low Self-Esteem Is a Risk Factor for Depressive Symptoms from Young Adulthood to Old Age. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2009, 118, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, C.; Richardson, T.; Maguire, N. Psychological Factors Associated with Financial Hardship and Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 77, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Diener, M. Cross-Cultural Correlates of Life Satisfaction and Self-Esteem. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfeld, P.; Brailovskaia, J.; Bieda, A.; Zhang, X.C.; Margraf, J. The Effects of Daily Stress on Positive and Negative Mental Health: Mediation through Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Xiao, H.; Chen, Y. Life Review for Chinese Older Adults in Nursing Homes: Cultural Acceptance and Its Effects. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Fung, H.H. Age Differences in Trust: An Investigation Across 38 Countries. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2013, 68, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, L.M.; Estrada, D.; Prada, S.I. Mental Health, Interpersonal Trust and Subjective Well-Being in a High Violence Context. SSM—Popul. Health 2019, 8, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, A.K.; Stanton, S.C.E.; Marshall, E.M. Social Network Structure and Combating Social Disconnection: Implications for Physical Health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P. Meaning in Life: One Link in the Chain From Religiousness to Well-Being. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the Meaning of Work: A Theoretical Integration and Review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrova, O.; Luhmann, M. Social Connectedness as a Source and Consequence of Meaning in Life. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillman, T.F.; Lambert, N.M.; Fincham, F.D.; Baumeister, R.F. Meaning as Magnetic Force: Evidence That Meaning in Life Promotes Interpersonal Appeal. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2011, 2, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Griffiths, M.D. The Relationship between Addictive Use of Social Media, Narcissism, and Self-Esteem: Findings from a Large National Survey. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, D.; Dong, Y. Self-Esteem and Problematic Smartphone Use Among Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model of Depression and Interpersonal Trust. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blairy, S.; Linotte, S.; Souery, D.; Papadimitriou, G.N.; Dikeos, D.; Lerer, B.; Kaneva, R.; Milanova, V.; Serretti, A.; Macciardi, F.; et al. Social Adjustment and Self-Esteem of Bipolar Patients: A Multicentric Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 79, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekierda, K.; Banik, A.; Park, C.L.; Luszczynska, A. Meaning in Life and Physical Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2017, 11, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shu, M. Mental health status, negative events and help-seeking behavior of college students: Based on the survey of the mental health status of college students in Jiangxi Province in the past ten years. Educ. Acad. Mon. 2013, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ge, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J. Applicability and generalizability of the revised meaning in life questionnaire: Based on classical test theory and multidimensional Rasch model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 23, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Slade, T. Interpreting Scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2001, 25, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, F.R.; Rosenberg, M.; McCord, J. Self-Esteem and Delinquency. J Youth Adolesc. 1978, 7, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. A New Scale for the Measurement of Interpersonal Trust1. J. Personal. 1967, 35, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, W. On the relationship between family socioeconomic status and Chinese undergraduates’ vocational selection anxiety under the context of the epidemic. J. Southwest China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 47, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, B. Effects of Mindfulness and Meaning in Life on Psychological Distress in Chinese University Students during the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Chained Mediation Model. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 53, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Xia, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, X. College Students’ Cyberloafing and the Sense of Meaning of Life: The Mediating Role of State Anxiety and the Moderating Role of Psychological Flexibility. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 905699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y. Thwarted Belongingness Hindered Successful Aging in Chinese Older Adults: Roles of Positive Mental Health and Meaning in Life. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 839125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Baumeister, R.F. Meaning in Life and Adjustment to Daily Stressors. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Strecher, V.J.; Kim, E.; Falk, E.B. Purpose in Life and Conflict-Related Neural Responses during Health Decision-Making. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Peng, J.; Gao, P.; Huang, H.; Cao, Y.; Zheng, L.; Miao, D. Relationship between Meaning in Life and Death Anxiety in the Elderly: Self-Esteem as a Mediator. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. The Relationship between Meaning in life and Resilience in Middle-aged adults: Mediating effect of Self-esteem. J. Digit. Converg. 2020, 18, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Deng, C.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Yang, J. Neural Processing of Personal, Relational, and Collective Self-Worth Reflected Individual Differences of Self-Esteem. J. Personal. 2022, 90, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelson, J.; Rollin, A.; Ridout, B.; Campbell, A. Internet-Delivered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Anxiety Treatment: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Xia, L.-X. The Relationship between Interpersonal Responsibility and Interpersonal Trust: A Longitudinal Study. Curr Psychol. 2019, 38, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, X.; Chi, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, J. Loneliness and Self-Esteem in Children and Adolescents Affected by Parental HIV: A 3-Year Longitudinal Study. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2019, 11, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manco, N.; Hamby, S. A Meta-Analytic Review of Interventions That Promote Meaning in Life. Am. J. Health Promot. 2021, 35, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Pi, Z.; Liu, R.; Li, X.; Wang, W. The Class Group Counseling on Life Education Improves Meaning in Life for Undergraduate Students. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 25345–25352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | N (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10–19 (very good mental health) | 422 (38.72%) | 14.96 | 2.99 |

| 20–24 (good mental health) | 292 (26.79%) | 21.86 | 1.39 |

| 25–29 (poor mental health) | 199 (18.26%) | 26.95 | 1.41 |

| 30–50 (very poor mental health) | 177 (16.24%) | 33.88 | 4.49 |

| Overall | 1090 (100%) | 22.07 | 7.36 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Kessler10 | 1 | |||

| 2. RMLQ | −0.318 *** | 1 | ||

| 3. RSES | −0.560 *** | 0.408 *** | 1 | |

| 4. ITS | −0.266 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.300 *** | 1 |

| Mean | 22.07 | 45.68 | 27.94 | 72.92 |

| SD | 7.36 | 9.77 | 4.50 | 8.48 |

| Path | Standardized Indirect Effect Value | Effect Amount | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Total effect | −0.589 | 100% | −0.789 | −0.389 |

| Direct effect | −0.204 | 34.63% | −0.353 | −0.054 |

| Total mediated effect | −0.386 | 65.53% | −0.494 | −0.278 |

| RMLQ → RSES → Kessler10 | −0.348 | 59.08% | −0.447 | −0.250 |

| RMLQ → ITS → Kessler10 | −0.028 | 4.75% | −0.052 | −0.005 |

| RMLQ → RESE → ITS→ Kessler10 | −0.009 | 1.53% | −0.018 | −0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, B.; Wang, A.; Ye, Y.; Liu, J.; Lin, L. The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Mental Health in Chinese Undergraduates: The Mediating Roles of Self-Esteem and Interpersonal Trust. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080720

Zhang B, Wang A, Ye Y, Liu J, Lin L. The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Mental Health in Chinese Undergraduates: The Mediating Roles of Self-Esteem and Interpersonal Trust. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):720. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080720

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Benyu, Anna Wang, Yuan Ye, Jiandong Liu, and Lihua Lin. 2024. "The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Mental Health in Chinese Undergraduates: The Mediating Roles of Self-Esteem and Interpersonal Trust" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080720

APA StyleZhang, B., Wang, A., Ye, Y., Liu, J., & Lin, L. (2024). The Relationship between Meaning in Life and Mental Health in Chinese Undergraduates: The Mediating Roles of Self-Esteem and Interpersonal Trust. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080720