Classification of Student Leadership Profiles in Diverse Governance Settings: Insights from Pisa 2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

Reflections of the Relationship between Leadership and Culture on Individuals

- According to the PISA 2022 data, do students have different leadership profiles?

- Do the leadership profiles exhibited by students vary between countries with different administrative styles and cultures?

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Data Collection Tools

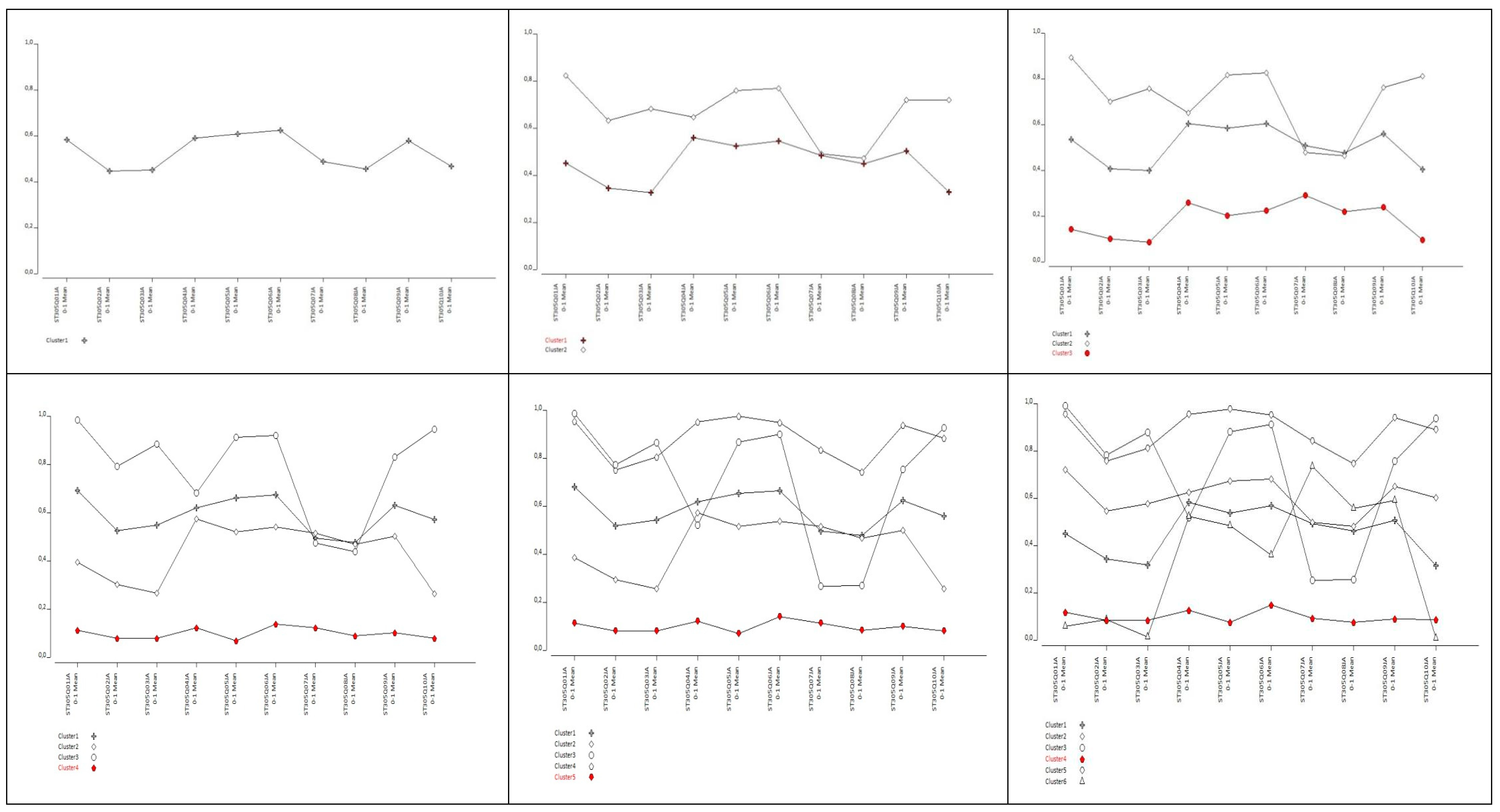

3. Findings

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Practical Implications

- Tailored leadership-development programs: The identification of different leadership profiles among students (e.g., “Moderate or Passive Leader Group”, “Strong Leader or Influential Group”, and “Avoidant or Discomfort with Leadership Group”) suggests the need for tailored leadership development programs in schools. Educators can design interventions that address the specific needs of each group, helping to nurture leadership potential across all students.

- Cultural sensitivity in leadership education: The observed variations in leadership profiles across countries highlight the importance of culturally sensitive approaches to leadership education. Educational policymakers should consider local cultural contexts when developing leadership curricula, ensuring that leadership concepts are relevant and applicable to students’ lived experiences.

- Governance and leadership skills: The apparent influence of national governance styles on student leadership profiles suggests that civic education and leadership training should incorporate understanding of governance systems. This could help students develop leadership skills that are both globally relevant and locally applicable.

- Early intervention: Given that this study focused on 15-year-old students, the results underscore the importance of early intervention in leadership development. Schools and educational systems should consider implementing leadership programs from an earlier age to foster these skills throughout a student’s educational journey.

- Cross-cultural leadership exchange: The diversity of leadership profiles across countries presents an opportunity for cross-cultural leadership exchange programs. Such initiatives could broaden students’ understanding of leadership and prepare them for leadership roles in an increasingly globalized world.

- Teacher training: Our findings imply a need for specialized teacher training in leadership education. Teachers should be equipped with the skills to identify different leadership tendencies in students and to nurture these appropriately.

- Assessment of leadership skills: The use of PISA data in this study suggests that standardized assessments could incorporate more comprehensive measures of leadership skills. This could provide valuable data for ongoing research and policy development in student leadership.

- Inclusive leadership education: The identification of an “Avoidant or Discomfort with Leadership Group” highlights the need for inclusive leadership education that addresses the barriers some students face in developing leadership skills.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Black, R.; Walsh, L.; Magee, J.; Hutchins, L.; Berman, N.; Groundwater-Smith, S. Student Leadership: A Review of Effective Practice; ARACY: Canberra, ACT, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gott, T.; Bauer, T.; Long, K. Student leadership today, professional employment tomorrow. New Dir. Stud. Leadersh. 2019, 2019, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eich, D. A grounded theory of high-quality leadership programs: Perspectives from student leadership development programs in higher education. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 15, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.M. Exploring instructional strategies in student leadership development programming. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2013, 6, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashkin, M.; Wren, J.T. Visionary Leadership. In The Leader’s Companion: Insights on Leadership through the Ages; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Seemiller, C. Assessing student leadership competency development. New Dir. Stud. Leadersh. 2016, 2016, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.J.; Rosenfield, D.; Gilbert, J.H.; Oandasan, I.F. Student leadership in interprofessional education: Benefits, challenges and implications for educators, researchers and policymakers. Med. Educ. 2008, 42, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimmock, C.; Walker, A. A cultural approach to leadership: Methodological issues. In Educational Leadership: Culture and Diversity; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, P.W.; Howell, J.P.; Hibino, S.; Lee, J.K.; Tate, U.; Bautista, A. Leadership in Western and Asian countries: Commonalities and differences in effective leadership processes across cultures. Leadersh. Q. 1997, 8, 233–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwairy, M. Culture and leadership: Personal and alternating values within inconsistent cultures. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 22, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euwema, M.C.; Wendt, H.; Van Emmerik, H. Leadership styles and group organizational citizenship behavior across cultures. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2007, 28, 1035–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogulu, U.D. Culturally-linked leadership styles. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2010, 31, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.I.; Wright, P.L. Leadership in the context of culture: An Egyptian perspective. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2004, 25, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, G.; Salmani, D.; Taatian, A. Survey of leadership styles in different cultures. Interdiscip. J. Manag. Stud. (Former. Known Iran. J. Manag. Stud.) 2010, 3, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Waldman, D.A.; Zhang, H. Strategic leadership across cultures: Current findings and future research directions. J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, B.; Moorman, H.; Nusche, D. Improving School Leadership; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; Volume 1, p. 578. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüş, S.; Şükrü Bellibaş, M.; Şen, S.; Hallinger, P. Finding the missing link: Do principal qualifications make a difference in student achievement? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2024, 52, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, T.; Teig, N. A systematic review of studies investigating the relationships between school climate and student outcomes in TIMSS, PISA, and PIRLS. In International Handbook of Comparative Large-Scale Studies in Education: Perspectives, Methods and Findings; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio Maia, J.; Rosa, V.; Mascarenhas, D.; Duarte Teodoro, V. Comparative indices of the education quality from the opinions of teachers and principals in TALIS 2018. Cogent Educ. 2022, 9, 2153418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teig, N.; Scherer, R.; Olsen, R.V. A systematic review of studies investigating science teaching and learning: Over two decades of TIMSS and PISA. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2022, 44, 2035–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKaabi, N.A.; Al-Maadeed, N.; Romanowski, M.H.; Sellami, A. Drawing lessons from PISA: Qatar’s use of PISA results. Prospects 2022, 54, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, L.; Saltelli, A.; Schnepf, S.V. Do PISA data justify PISA-based education policy? Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2017, 19, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białecki, I.; Jakubowski, M.; Wiśniewski, J. Education policy in Poland: The impact of PISA (and other international studies). Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.M.; Costa, E.; Gonçalves, C. Fifteen years looking at the mirror: On the presence of PISA in education policy processes (Portugal, 2000–2016). Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, M.; Martens, K. Towards an education approach à la finlandaise? French education policy after PISA. J. Educ. Policy 2012, 27, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, D.; Martens, K.; Teltemann, J. PISA and its consequences: Shaping education policies through international comparisons. Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautalin, M.; Alasuutari, P.; Vento, E. Globalisation of education policies: Does PISA have an effect? J. Educ. Policy 2019, 34, 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, A.; Zoido, P. The policies that shaped PISA, and the policies that PISA shaped. In The Handbook of Global Education Policy; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellar, S.; Lingard, B. Looking East: Shanghai, PISA 2009 and the reconstitution of reference societies in the global education policy field. Comp. Educ. 2013, 49, 464–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, N. The impact of OECD-PISA results on Japanese educational policy. Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldow, F. What PISA did and did not do: Germany after the ‘PISA-shock’. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2009, 8, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, J.; Dalle, A.; Dj, S.; Irmawati, I. PISA assessment on reading literacy competency: Evidence from students in urban, mountainous and island areas. J. Kependidikan: J. Has. Penelit. Dan Kaji. Kepustakaan Bid. Pendidik. Pengajaran Dan Pembelajaran 2023, 9, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopfenbeck, T.N.; Kjærnsli, M. Students’ test motivation in PISA: The case of Norway. Curric. J. 2016, 27, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrim, J.; Moss, G. The link between fiction and teenagers’ reading skills: International evidence from the OECD PISA study. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 45, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrim, J.; Lopez-Agudo, L.A.; Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O.D. The impact of test language on PISA scores. New evidence from Wales. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 48, 420–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavonen, J.; Laaksonen, S. Context of teaching and learning school science in Finland: Reflections on PISA 2006 results. J. Res. Sci. Teach. Off. J. Natl. Assoc. Res. Sci. Teach. 2009, 46, 922–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T.D.; Zeidler, D.L. Scientific literacy, PISA, and socioscientific discourse: Assessment for progressive aims of science education. J. Res. Sci. Teach. Off. J. Natl. Assoc. Res. Sci. Teach. 2009, 46, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, K. The PISA view of mathematical literacy in Indonesia. J. Math. Educ. 2011, 2, 95–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teig, N.; Scherer, R.; Kjærnsli, M. Identifying patterns of students’ performance on simulated inquiry tasks using PISA 2015 log-file data. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2020, 57, 1400–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, L. How does ICT use influence students’ achievements in math and science over time? Evidence from PISA 2000 to 2012. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2016, 12, 2431–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, S.; Karacay, G.; Dastmalchian, A.; Kabasakal, H. Organizational culture and leadership in Egypt, Iran, and Turkey: The contextual constraints of society and industry. Can. J. Adm. Sci./Rev. Can. Des Sci. De L’administration 2022, 39, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Resick, C.J.; Martin, G.S.; Keating, M.A.; Dickson, M.W.; Kwan, H.K.; Peng, C. What ethical leadership means to me: Asian, American, and European perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Does the transactional–transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, J.; Pieczonka, A.; Eisenring, M.; Mironski, J. Poland, a workforce in transition: Exploring leadership styles and effectiveness of Polish vs. Western expatriate managers. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2015, 20, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.; Ferreira, M.C.; Assmar EM, L.; Baris, G.; Berberoglu, G.; Dalyan, F.; Wong, C.C.; Hassan, A.; Hanke, K.; Boer, D. Organizational practices across cultures: An exploration in six cultural contexts. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2014, 14, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Cho, Y.; Froese, F.J.; Shin, M. The effect of leadership styles, rank, and seniority on affective organizational commitment: A comparative study of US and Korean employees. Cross Cult. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, P.; Crawford, J. The effect of organisational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction and organisational commitment: A cross-national comparison. J. Manag. Dev. 2004, 23, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, B.J. Role Theory: Expectations, Identities, and Behaviors; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Polzer, J.T. Role theory. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, M.P.; Shang, Y.; Richards, M.; Zhu, X. Two sides of the same coin? Leadership and organizational culture. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 975–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivers-Blackwell, S.L. Using role theory to examine determinants of transformational and transactional leader behavior. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2004, 10, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Sorensen, N.; Reber, R.; Chen, S.X. Connecting and separating mind-sets: Culture as situated cognition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arun, K.; Kahraman Gedik, N. Impact of Asian cultural values upon leadership roles and styles. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2022, 88, 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, S.; Freeman, B.; Tickner, A. How Connected Leadership Helps to Create More Agile and Customer-Centric Organizations in Asia. In The Palgrave Handbook of Leadership in Transforming Asia; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Park, J.H.; Kim, H.J. South Korean humanistic leadership. Cross Cult. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 27, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vliert, E. Climate, Affluence, and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, B.; Spencer, S.M.; Zhu, G. Thinking globally, leading locally: Chinese, Indian, and Western leadership. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 19, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, J. Constructing theory for leadership in intercultural contexts. J. Educ. Adm. 2007, 45, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Runde, C.; Nardon, L.; Steers, R.M. Looking beyond Western leadership models: Implications for global managers. Organ. Dyn. 2011, 40, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayman, R.; Chemers, M.M.; Fiedler, F. The contingency model of leadership effectiveness: Its levels of analysis. In Leadership: Understanding the Dynamics of Power and Influence in Organizations, 2nd ed.; Vecchio, R.P., Ed.; University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2007; pp. 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidan, M.; Dastmalchian, A. Managerial implications of the GLOBE project: A study of 62 societies. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2009, 47, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q. Navigating Educational Challenges in Cambodia: Insights from China’s Vocational Education Assistance Programs. Int. J. Educ. Humanit. 2024, 12, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhokar, J.; Brodbeck, F.; House, R. Culture and Leadership across the World; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1005–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P. Cultures of educational leadership: Researching and theorising common issues in different world contexts. In Cultures of Educational Leadership: Global and Intercultural Perspectives; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A. The impact of leadership on good governance in post civil war in Somalia. Int. Soc. Ment. Res. Think. J. 2021, 7, 2488–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Barthold, C.; Checchi, M.; Imas, M.; Smolović Jones, O. Dissensual leadership: Rethinking democratic leadership with Jacques Rancière. Organization 2022, 29, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastil, J. A definition and illustration of democratic leadership. Hum. Relat. 1994, 47, 953–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpia, H.; Devos, G. How distributed leadership can make a difference in teachers’ organizational commitment? A qualitative study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz-Niño, C.; Blanco-Encomienda, F.J. Participation in decision-making processes of community development agents: A study from Peru. Community Dev. J. 2019, 54, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. Giving peace a chance: Organizational leadership, empowerment, and peace. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2007, 28, 1077–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P.A. Democratic leadership: Drawing distinctions with distributed leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2004, 7, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, G.; Nayak, R.; Ngyyen, T. Review of research for two decades for women leadership in higher education around the world and in Vietnam: A comparative analysis. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 36, 640–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, S.; Donovan, T. Democracy, institutions and attitudes about citizen influence on government. Br. J. Political Sci. 2002, 32, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. To know democracy is to love it: A cross-national analysis of democratic understanding and political support for democracy. Political Res. Q. 2014, 67, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, W.H. Democracy, experience, and education: Promoting a continued capacity for growth. Phi Delta Kappan 2003, 84, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, J.M.; Ghani MF, A. International school leadership in Malaysia: Exploring teachers’ perspectives on leading in a culturally diverse environment. Malays. Online J. Educ. Manag. 2019, 7, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adıgüzel, Z.; Özçınar, M.F.; Karadal, H. Examination of the effects of authoritarian leadership on employees in production sector. Turk. Soc. 2020, 15, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barański, M. The political party system in Slovakia in the era of Mečiarism. The experiences of the young democracies of central European countries. East. Rev. 2020, 2020, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. ‘Staying in the Nationalist Bubble’: Social Capital, Culture Wars, and the COVID-19 Pandemic. M/C J. 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, O.; de Zavala, A.G. Collective narcissism and weakening of American democracy. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2021, 21, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, H. Study on authoritarian leader-member relationship. J. US-China Public Adm. 2015, 12, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.; Li, Y. Authoritarian leadership and nurse presenteeism: The role of workload and leader identification. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulova, F.; Anguelovski, I.; Argüelles, L.; Conill, J. A ‘fertile soil’for sustainability-related community initiatives: A new analytical framework. Environ. Plan. A 2017, 49, 2362–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, S.; Romera, Á.J.; Beskow, W.B.; Lovatt, S.J. Better simulation modelling to support farming systems innovation: Review and synthesis. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 51, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, K.V.S. Does competence make citizens tolerate undemocratic behavior? Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2022, 116, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passini, S.; Morselli, D. Disobeying an illegitimate request in a democratic or authoritarian system. Political Psychol. 2010, 31, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonovits, G.; McCoy, J.; Littvay, L. Democratic hypocrisy and out-group threat: Explaining citizen support for democratic erosion. J. Politics 2022, 84, 1806–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, H.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Meyer, K. The relationship between gender equality and democracy: A comparison of arab versus non-arab muslim societies. Sociology 2007, 41, 1151–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowers, K.; Hancock, G.M.; Neigel, A.; Cha, J.; Chong, I.; Durso, F.T.; Peres, S.C.; Stone, N.J.; Summers, B. HeForShe in HFE: Strategies for Enhancing Equality in Leadership for All Allies. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Sage, CA, USA, 28 October–1 November 2019; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 63, pp. 622–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Fidalgo, A. The face of the party: Party leadership selection, and the role of family and faith. Political Res. Q. 2021, 75, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastmalchian, A.; Javidan, M.; Alam, K. Effective leadership and culture in Iran: An empirical study. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 532–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.C. Chinese culture and leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2001, 4, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luschei, T.F.; Jeong, D.W. School governance and student achievement: Cross-national evidence from the 2015 PISA. Educ. Adm. Q. 2021, 57, 331–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T.; Haiyan, Q. Leadership and culture in Chinese education. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2000, 20, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oplatka, I.; Arar, K.H. Leadership for social justice and the characteristics of traditional societies: Ponderings on the application of western-grounded models. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2016, 19, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T.; Glover, D. School leadership models: What do we know? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2014, 34, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Gorgen, K. Successful School Leadership; Education Development Trust: Reading Berkshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Flessa, J.; Bramwell, D.; Fernandez, M.; Weinstein, J. School leadership in Latin America 2000–2016. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 182–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2005, 4, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, E.; Loeb, S. New thinking about instructional leadership. Phi Delta Kappan 2010, 92, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, R. Another fine mess you’ve gotten me into: Effective leadership in a difficult place. In The Art and Science of Working Together; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Sánchez, S.E.; Gibbons, J.L.; Grazioso MD, P.; Ureta Morales, F.J.; García de la Cadena, C. Social axioms mediate gender differences in gender ideologies among Guatemalan university students. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2022, 53, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, A. Trouble in Central America: Guatemala on the brink. J. Democr. 2010, 21, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. Guatemala: The Education Sector; Guatemala Poverty Assessment Program (GUAPA) of the World Bank: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sitha, C. The way forward for education reform in Cambodia. In The Political Economy of Schooling in Cambodia: Issues of Quality and Equity; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheang, T. Leading educational reconstruction in post-conflict Cambodia: Perspectives of primary school leaders. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 52, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.H.; Kitamura, Y.; Zimmerman, T. Privatization and Teacher Education in Cambodia: Implications for Equity; Open Society Foundations: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guadalupe, C.; León, J.; Cueto, S. Charting Progress in Learning Outcomes in Peru Using National Assessments; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Balarin, M. The slow development process of educational policies in Peru. In Examining Educational Policy in Latin America; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J. Making sense of distributed leadership: The case of peer assistance and review. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2004, 26, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodas Garay, C.D. La formación docente continua y los procesos de transformación educativa de Paraguay. Rev. Científica En Cienc. Soc. 2023, 5, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, L.R.; Wångby, M. The person-oriented approach: A short theoretical and practical guide. Eest. Haridusteaduste Ajakiri. Est. J. Educ. 2014, 2, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankaraš, M.; Vermunt, J.K.; Moors, G. Measurement equivalence of ordinal items: A comparison of factor analytic, item response theory, and latent class approaches. Sociol. Methods Res. 2011, 40, 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund-Gibson, K.; Choi, A.Y. Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2018, 4, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education; PISA, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2022 Results (Volume II): Learning During–and from–Disruption; PISA, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Educational Testing Service. Computer-Based Student Questionnaire for PISA 2022: Main Survey Version. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2022database/CY8_202111_QST_MS_STQ_CBA_NoNotes.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- OECD. PISA 2022 Database; OECD: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2022database/ (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Hagenaars, J.A.; McCutcheon, A.L. (Eds.) Applied Latent Class Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, S.T.; Collins, L.M.; Lemmon, D.R.; Schafer, J.L. PROC LCA: A SAS procedure for latent class analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.F. Latent Structure Analysis and Its Relation to Factor Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuaresma-Escobar, K.J. Nailing the situational leadership theory by synthesizing the culture and nature of principals’ leadership and roles in school. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2021, 5 (Suppl. S3), 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M. Culture and leadership across the world: The globe book of in-depth studies of 25 societies. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2012, 18, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, R.; Çoban, Ö. Leadership map of seven countries according to talis 2018. Int. J. Eurasian Educ. Cult. 2021, 6, 2166–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Wanasika, I.; Laiho, M. Cultural Differences in Communication and Leadership: A Comparison of Finland, Indonesia and USA. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance ECMLG 2022; Academic Publishing International: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Janićijević, N. The impact of national culture on leadership. Econ. Themes 2019, 57, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, N.B. Cultural influences on leadership: Western-dominated leadership and non-Western conceptualizations of leadership. Sociol. Anthropol. 2020, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmir, M.; Esfahani, M.; Emami, M. An investigation on leadership styles in different cultures. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. Forthcom. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2013, 3, 1491–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Congressional Research Service. Congressional Research Service. In Focus. 2023. Available online: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF12340.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Westendorff, R.E.A.; Mutch, C.; Mutch, N.T. When COVID-19 is only part of the picture: Caring pedagogy in higher education in Guatemala. Pastor. Care Educ. 2021, 39, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milian, M.; Walker, D. Bridges to bilingualism: Teachers’ roles in promoting Indigenous languages in Guatemala. FIRE Forum Int. Res. Educ. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.M.; Ashdown, B.K. When COVID affects the community: The response of a needs-based private school in Guatemala. Local Dev. Soc. 2020, 1, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, N.; Heneine, E.M.; MacDermod, C.M.; Perez, M.L.; Boyd, D.L. Assessment of Maya women’s knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs on sexually transmitted infections in Guatemala: A qualitative pilot study. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviedo Gasparico, L. The Guatemalan Education System: Realities and Challenges. In The Education Systems of the Americas; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M.C.; Burgin, X. Exploring the funds of knowledge with 108 Guatemalan teachers. Gist Educ. Learn. Res. J. 2019, 18, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, M.; Valdivia, M. Educational Challenges in Guatemala and Consequences for Human Capital and Development; Inter-American Dialogue: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Croissant, A. The Perils and Promises of Democratization through United Nations Transitional Authority–Lessons from Cambodia and East Timor. In War and Democratization; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, S.D.; Lamb, E.; Samet, O. Promoting democracy under electoral authoritarianism: Evidence from Cambodia. Comp. Political Stud. 2023, 56, 1029–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Un, K. Cambodia: Moving away from democracy? Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2011, 32, 546–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R. Peacebuilding, democratization, and political reconciliation in Cambodia. Asian J. Peacebuilding 2020, 8, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. Development through vocational education. the lived experiences of young people at a vocational education, training restaurant in Siem reap, Cambodia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, M.; Kobakhidze, M.N.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J. The hidden curriculum in a hidden marketplace: Relationships and values in Cambodia’s shadow education system. J. Curric. Stud. 2018, 50, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phin, C. Challenges of Cambodian teachers in contributing to human and social development: Are they well trained? Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2014, 4, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. Education reforms in Cambodia: Issues and concerns. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2007, 6, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağce, H.E. Parlamenter ve başkanlık sistemiyle yönetilen ülkelerde gelir dağılımı eşitsizliği ve yoksulluk. İnsan İnsan 2017, 4, 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarza Paredes, D.; Suarez Enciso, S. The Education System of Paraguay: Trends and Issues. In The Education Systems of the Americas; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beittel, J.S. Paraguay: In Brief; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brizuela, C. Paraguay: An overview In Education in South America; Schwartzman, S., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2015; pp. 363–383. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Public Governance Reviews: Paraguay: Pursuing National Development through Integrated Public Governance; OECD Public Governance Reviews; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miş, N.; Aslan, A.; Duran, H.; Ayvaz, M.E. Dünyada Başkanlık Sistemi Uygulamaları [2. Baskı]; Seta: Ankara, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, D.S. Peru: Democratic Forms, Authoritarian Practices. In Latin American Politics and Development, 5th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 228–258. [Google Scholar]

- de Mello, J.C. Democracia em crise: A política do caos no Peru contemporâneo em meio à potência cultural. Em Tempo de Histórias 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF Western Hemisphere Department. Peru: 2023 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Peru. IMF Staff Country Reports. 2023. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/03/24/Peru-2023-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-Statement-by-the-Executive-531362 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Valdivia, F.R.M. La descentralización centralista en el Perú: Entre la crisis y el crecimiento 1970–2014. Investig. Soc. 2015, 19, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.S.; Gracia, E.P.; Puño-Quispe, L.; Hurtado-Mazeyra, A. Quality and equity in the Peruvian education system: Do they progress similarly? Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 119, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arista, L.M.V.; Ramos, J.E.A.; Matienzo, M.S. The Education System of Peru. In The Education Systems of the Americas; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2021; p. 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueto, S.; León, J.; Miranda, A. Peru: Impact of socioeconomic gaps in educational outcomes. In Education in South America; Schwartzman, S., Ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 385–404. [Google Scholar]

| Item Code | Item Content | Response Range |

|---|---|---|

| ST305Q01JA | I am comfortable with taking the lead role in group. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| ST305Q02JA | I know how to convince others to do what I want. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| ST305Q03JA | I enjoy leading others. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| ST305Q04JA | I keep my opinions to myself in group discussions. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| ST305Q05JA | I speak up to others about things that matter to me. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| ST305Q06JA | I take the initiative when working with my classmates. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| ST305Q07JA | I wait for others to take a lead. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| ST305Q08JA | I find it hard to influence people. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| ST305Q09JA | I want to be in charge. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| ST305Q10JA | I like to be a leader in my class. | 1/2/3/4/5 |

| Model | BIC * | Number of Parameters | Classification Error | Class Sizes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 class | 387,863.05 | 40 | 0.0000 | - |

| 2 classes | 373,798.69 | 51 | 0.0748 | 0.65/0.35 |

| 3 classes | 366,710.96 | 62 | 0.0604 | 0.73/0.21/0.06 |

| 4 classes | 362,695.14 | 73 | 0.1155 | 0.50/0.38/0.08/0.04 |

| 5 classes | 360,680.68 | 84 | 0.1191 | 0.51/0.36/0.06/0.03/0.04 |

| 6 classes | 358,941.71 | 95 | 0.1321 | 0.45/0.41/0.05/0.03/0.03/0.03 |

| Item | Item Level | 2-Class Latent Model | 3-Class Latent Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 (0.6460) | Cluster 2 (0.3540) | Cluster 1 (0.7259) | Cluster 2 (0.2074) | Cluster 3 (0.0667) | ||

| (ST305Q01JA) I am comfortable with taking the role in a group. | Strongly disagree | 0.9833 | 0.0167 | 0.5047 | 0.0031 | 0.4922 |

| Disagree | 0.9672 | 0.0328 | 0.9040 | 0.0043 | 0.0917 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.8660 | 0.1340 | 0.9636 | 0.0194 | 0.0170 | |

| Agree | 0.5178 | 0.4822 | 0.7806 | 0.2115 | 0.0078 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.1302 | 0.8698 | 0.2414 | 0.7521 | 0.0065 | |

| (ST305Q02JA) I know how to convince others to do what I want. | Strongly disagree | 0.8694 | 0.1306 | 0.5724 | 0.0754 | 0.3522 |

| Disagree | 0.8424 | 0.1576 | 0.8897 | 0.0555 | 0.0548 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.6360 | 0.3640 | 0.8220 | 0.1695 | 0.0086 | |

| Agree | 0.4023 | 0.5977 | 0.6384 | 0.3576 | 0.0040 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.1516 | 0.8484 | 0.2547 | 0.7433 | 0.0019 | |

| (ST305Q03JA) I enjoy leading others. | Strongly disagree | 0.9254 | 0.0746 | 0.5886 | 0.0342 | 0.3772 |

| Disagree | 0.8925 | 0.1075 | 0.9140 | 0.0327 | 0.0534 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.6466 | 0.3534 | 0.8531 | 0.1421 | 0.0047 | |

| Agree | 0.3359 | 0.6641 | 0.6098 | 0.3870 | 0.0032 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.0776 | 0.9224 | 0.1528 | 0.8471 | 0.0001 | |

| (ST305Q04JA) I keep my opinions to myself in group discussions. | Strongly disagree | 0.7484 | 0.2516 | 0.3820 | 0.2000 | 0.4180 |

| Disagree | 0.7061 | 0.2939 | 0.7261 | 0.1737 | 0.1002 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.6840 | 0.3160 | 0.8093 | 0.1678 | 0.0229 | |

| Agree | 0.6524 | 0.3476 | 0.8084 | 0.1702 | 0.0215 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.4193 | 0.5807 | 0.5224 | 0.4487 | 0.0289 | |

| (ST305Q05JA) I speak up to others about things that matter to me. | Strongly disagree | 0.9257 | 0.0743 | 0.4192 | 0.0347 | 0.5461 |

| Disagree | 0.8840 | 0.1160 | 0.8647 | 0.0344 | 0.1009 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.7725 | 0.2275 | 0.8856 | 0.0878 | 0.0266 | |

| Agree | 0.5822 | 0.4178 | 0.7675 | 0.2182 | 0.0143 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.2859 | 0.7141 | 0.3962 | 0.5903 | 0.0135 | |

| (ST305Q06JA) I take the initiative when working with my classmates. | Strongly disagree | 0.9548 | 0.0452 | 0.3939 | 0.0150 | 0.5911 |

| Disagree | 0.9066 | 0.0934 | 0.8464 | 0.0245 | 0.1291 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.7746 | 0.2254 | 0.8903 | 0.0850 | 0.0246 | |

| Agree | 0.5934 | 0.4066 | 0.7735 | 0.2097 | 0.0168 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.2576 | 0.7424 | 0.3542 | 0.6296 | 0.0162 | |

| (ST305Q07JA) I wait for others to take the lead. | Strongly disagree | 0.5933 | 0.4067 | 0.3930 | 0.3276 | 0.2794 |

| Disagree | 0.6636 | 0.3364 | 0.7427 | 0.1938 | 0.0635 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.6570 | 0.3430 | 0.8117 | 0.1681 | 0.0202 | |

| Agree | 0.6729 | 0.3271 | 0.8042 | 0.1667 | 0.0291 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.5200 | 0.4800 | 0.5658 | 0.3610 | 0.0731 | |

| (ST305Q08JA) I find it hard to influence people. | Strongly disagree | 0.6242 | 0.3758 | 0.4068 | 0.2976 | 0.2956 |

| Disagree | 0.6797 | 0.3203 | 0.7628 | 0.1755 | 0.0616 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.6451 | 0.3549 | 0.7943 | 0.1849 | 0.0207 | |

| Agree | 0.6494 | 0.3506 | 0.7894 | 0.1885 | 0.0221 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.4975 | 0.5025 | 0.5732 | 0.3808 | 0.0461 | |

| (ST305Q09JA) I want to be in charge. | Strongly disagree | 0.8779 | 0.1221 | 0.4557 | 0.0713 | 0.4730 |

| Disagree | 0.8683 | 0.1317 | 0.8671 | 0.0527 | 0.0802 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.7061 | 0.2939 | 0.8356 | 0.1405 | 0.0239 | |

| Agree | 0.5642 | 0.4358 | 0.7478 | 0.2324 | 0.0197 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.3474 | 0.6526 | 0.4574 | 0.5164 | 0.0262 | |

| (ST305Q10JA) I like to be a leader in my class. | Strongly disagree | 0.9553 | 0.0447 | 0.6232 | 0.0171 | 0.3597 |

| Disagree | 0.9234 | 0.0766 | 0.9249 | 0.0156 | 0.0595 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.6702 | 0.3298 | 0.8903 | 0.1036 | 0.0060 | |

| Agree | 0.3192 | 0.6808 | 0.6013 | 0.3954 | 0.0033 | |

| Strongly agree | 0.0859 | 0.9141 | 0.1674 | 0.8291 | 0.0035 | |

| Country | 2-Class Latent Model | 3-Class Latent Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | |

| Cambodia | 0.8262 | 0.1738 | 0.8735 | 0.0595 | 0.0670 |

| Guatemala | 0.5763 | 0.4237 | 0.6504 | 0.2781 | 0.0715 |

| Paraguay | 0.5610 | 0.4390 | 0.6628 | 0.2691 | 0.0681 |

| Peru | 0.0004 | 0.9996 | 0.0028 | 0.9972 | 0.0000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Görgülü, D.; Coşkun, F.; Sipahioğlu, M.; Demir, M. Classification of Student Leadership Profiles in Diverse Governance Settings: Insights from Pisa 2022. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080718

Görgülü D, Coşkun F, Sipahioğlu M, Demir M. Classification of Student Leadership Profiles in Diverse Governance Settings: Insights from Pisa 2022. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):718. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080718

Chicago/Turabian StyleGörgülü, Deniz, Fatma Coşkun, Mete Sipahioğlu, and Mustafa Demir. 2024. "Classification of Student Leadership Profiles in Diverse Governance Settings: Insights from Pisa 2022" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080718

APA StyleGörgülü, D., Coşkun, F., Sipahioğlu, M., & Demir, M. (2024). Classification of Student Leadership Profiles in Diverse Governance Settings: Insights from Pisa 2022. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080718