Analysis of Factors Contributing to State Body Appreciation during Exercise

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Importance of Positive Body Image for Exercise Adherence

1.2. Factors Contributing to Body Appreciation during Exercise

1.3. The Importance of Body Appreciation, Body Surveillance, Enjoyment, and Mindfulness during Physical Activity for Exercise Adherence in Higher Body Mass Exercisers

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Setting and Procedures

2.3. Study Measures

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Contributing to Body Appreciation during Exercise

4.2. Analysis of Factors Contributing to Body Appreciation during Physical Activity in Exercisers of Different Exercise Experiences and Body Masses

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Posadzki, M.; Pieper, P.; Pajpai, D.; Makaruk, R.; Konsgen, H.; Neuhaus, N.; Semwal, A. Exercise/Physical Activity and Health Outcomes: An Overview of Cochrane Systematic Reviews. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.; Sarmento, H.; Martins, J.; Saboga Nunes, L. Prevalence of Physical Activity in European adults: Compliance with the World Health Organization’s Physical Activity Guidelines. Prev. Med. 2015, 1, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Llamas, A.; García-Mayor, J.; De la Cruz-Sánchez, E. How Europeans Move: A Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity and Sitting Time Paradox in the European Union. Public Health 2022, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitara, K.; Odani, S.; Demenagas, N.; Rachiotis, G.; Symvoulakis, E.; Vardavas, C. Prevalence and Correlates of Physical Inactivity in Adults across 28 European Countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabiston, C.M.; Pila, E.; Vani, M.; Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. Body Image, Physical Activity, and Sport: A Scoping Review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 1, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N.L. What Is and What Is Not Positive Body Image? Conceptual Foundations and Construct Definition. Body Image 2015, 14, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vani, M.F.; Murray, R.M.; Sabiston, C.M. Body Image and Physical Activity. In Essentials of Exercise and Sport Psychology: An Open Access Textbook; Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology: Hayward, CA, USA, 2021; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; Bassett-Gunter, R.L.; Conlin, C. Body Image and Exercise. In Oxford Handbook of Exercise Psychology; Acevedo, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Engeln, R.; Shavlik, M.; Daly, C. Tone it Down: How Fitness Instructors’ Motivational Comments Shape Women’s Body Satisfaction. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2018, 12, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, I.; Tiggemann, M. Objectification in Fitness Centers: Self-Objectification, Body Dissatisfaction, and Disordered Eating in Aerobic Instructors and Aerobic Participants. Sex Roles 2005, 53, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, E.L.; Schneider, J.; Gentili, C.; Tinoco, A.; Silva-Breen, H.; White, P.; LaVoi, N.M.; Diedrichs, P.C. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventions that Target the Intersection of Body Image and Movement among Girls and Women. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R. Associations between Body Appreciation and Disordered Eating in a Large Sample of Adolescents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulliard, Z.A.; Kauffman, A.A.; Fitterman-Harris, H.; Perry, J.E.; Ross, M.J. Examining Positive Body Image, Sport Confidence, Flow State, and Subjective Performance among Student Athletes and Non-Athletes. Body Image 2019, 28, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, K.J.; Tylka, T.L. Appearance-Based Exercise Motivation Moderates the Relationship between Exercise Frequency and Positive Body Image. Body Image 2014, 11, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, M.; Dittmar, H.; Banerjee, R.; Bond, R. ‘I Just Feel So Guilty’: The Role of Introjected Regulation in Linking Appearance Goals for Exercise with Women’s Body Image. Body Image 2017, 20, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J.; McClure, Z.; Tylka, T.L.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Body Appreciation and its Psychological Correlates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Body Image 2022, 42, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, K.J. Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of a State Version of the Body Appreciation Scale-2. Body Image 2016, 19, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Roberts, T.A. Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychol. Women Q. 1997, 21, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E.K.; Creswell, J.D. Mechanisms of Mindfulness Training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 1, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Williams, G.C.; Patrick, H.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and Physical Activity: The Dynamics of Motivation in Development and Wellness. Hell. J. Psychol. 2009, 6, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, D.A.; Tylka, T.L.; Rodgers, R.F.; Convertino, L.; Pennesi, J.L.; Parent, M.C.; Brown, T.A.; Compte, E.J.; Cook-Cottone, C.P.; Crerand, C.E.; et al. Pathways from Sociocultural and Objectification Constructs to Body Satisfaction among Men: The U.S. Body Project I. Body Image 2022, 41, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, E.A.; Zurbriggen, E.L.; Ward, L.M. Becoming an Object: A Review of Self-Objectification in Girls. Body Image 2020, 33, 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayeh, A.L.; Lewis, B.A. The Effect of Mirrors on Women’s State Body Image Responses to Yoga. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 35, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahalon, R.; Shnabel, N.; Becker, J.C. Experimental Studies on State Self-Objectification: A Review and an Integrative Process Model. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alleva, J.M.; Tylka, T.L. Body Functionality: A Review of the Literature. Body Image 2021, 36, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilchrist, J.D.; Pila, E.; Lucibello, K.M.; Sabiston, C.M.; Conroy, D.E. Body Surveillance and Affective Judgments of Physical Activity in Daily Life. Body Image 2021, 1, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; McEwan, D.; Rebar, A.L. Theories of Physical Activity Behaviour Change: A History and Synthesis of Approaches. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich-French, S.; Cox, A.E.; Huong, C. The State Mindfulness Scale for Physical Activity 2: Expanding the Assessment of Monitoring and Acceptance. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2022, 26, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Forge, R. Aligning Mind and Body: Exploring the Disciplines of Mindful Exercise. ACSM’s Health Fit. J. 2005, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.E.; Tylka, T.L. A Conceptual Model Describing Mechanisms for How Yoga Practice May Support Positive Embodiment. Eat. Disord. 2020, 28, 376–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankauskiene, R.; Baceviciene, M. Mindful Monitoring and Accepting the Body in Physical Activity Mediates the Associations between Physical Activity and Positive Body Image in a Sample of Young Physically Active Adults. Front. Sports Act Living 2024, 6, 1360145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.H.; Conroy, D.E. Mindfulness and Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Hierarchical Model of Mindfulness. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 18, 794–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thedinga, H.K.; Zehl, R.; Thiel, A. Weight Stigma Experiences and Self-Exclusion from Sport and Exercise Settings among People with Obesity. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 565. [Google Scholar]

- Lessard, L.M.; Puhl, R.M.; Himmelstein, M.S.; Pearl, R.L.; Foster, G.D. Eating and Exercise-Related Correlates of Weight Stigma: A Multinational Investigation. Obesity 2021, 29, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horenstein, A.; Kaplan, S.C.; Butler, R.M.; Heimberg, R.G. Social Anxiety Moderates the Relationship Between Body Mass Index and Motivation to Avoid Exercise. Body Image 2021, 36, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Lind, E. Exercise Does Not Feel the Same When You Are Overweight: The Impact of Self-Selected and Imposed Intensity on Affect and Exertion. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankauskiene, R.; Balciuniene, V.; Rutkauskaite, R.; Pajaujiene, S.; Baceviciene, M. Evaluating the Impact of the Nirvana Fitness and Functional Training Programmes on Young Women’s State Body Appreciation and its Correlates. Healthcare, 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- McKinley, N.M.; Hyde, J.S. The Objectified Body Consciousness Scale: Development and Validation. Psychol. Women Q. 1996, 20, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urvelyte, E. Studenčių Pozityvaus Kūno Vaizdo Skatinimo Intervencijos Veiksmingumas, Atsižvelgiant į Pozityvaus Kūno Vaizdo Modelio Komponentus (Effectiveness of Intervention to Enhance Positive Body Image in Female Students in Relation to the Components of the Positive Body Image Model). Ph.D. Thesis, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R.; Balciuniene, V. Mindfulness, Physical Activity and Sports Participation: Validity Evidence of the Lithuanian Translation of the State Mindfulness Scale for Physical Activity 2 in Physically Active Young Adults. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markland, D.; Tobin, V. A Modification to the Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire to Include an Assessment of Amotivation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2004, 26, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R. Self-Determined Motivation Mediates the Association between Self-Reported Availability of Green Spaces for Exercising and Physical Activity: An Explorative Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishner, D.A.; Cooter, A.B.; Zald, D.H. Addressing Measurement Limitations in Affective Rating Scales: Development of an Empirical Valence Scale. Cogn. Emot. 2008, 22, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Alam, M.K.; Rao, M.B. Sample Size Calculations in Simple Linear Regression: A New Approach. Entropy 2023, 25, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Coutts, J.J. Use Omega Rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for Estimating Reliability. But…. Commun. Methods Meas. 2020, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha when Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Methodological Issues and Strategies in Clinical Research, 4th ed.; A Power Primer; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; 279p. [Google Scholar]

- Kutner, M.H.; Nachtsheim, C.J.; Neter, J. Applied Linear Statistical Models, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, A.E.; Ullrich-French, S.; Cole, A.N.; D’Hondt-Taylor, M. The Role of State Mindfulness During Yoga in Predicting Self-Objectification and Reasons for Exercise. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 22, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeln, R.; Goldenberg, C.; Jenkins, M. Body Surveillance May Reduce the Psychological Benefits of Exercise. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 42, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, R.M.; Tylka, T.L.; McHilley, B.H.; Stump, K.N.P. Attunement with Exercise (AWE). In Handbook of Positive Body Image and Embodiment; Tylka, T.L., Piran, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Cottone, C.P. Incorporating Positive Body Image into the Treatment of Eating Disorders: A Model for Attunement and Mindful Self-Care. Body Image 2015, 14, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, J.E.; Thompson, J.K.; Levine, M.P. Development and Validation of the Physical Activity Body Experiences Questionnaire. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2019, 83, 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piran, N. The Experience of Embodiment Construct: Reflecting the Quality of Embodied Lives. In Handbook of Positive Body Image and Embodiment: Constructs, Protective Factors, and Interventions; Tylka, T.L., Piran, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tsafou, K.E.; Lacroix, J.P.; Van Ee, R.; Vinkers, C.D.; De Ridder, D.T. The Relation of Trait and State Mindfulness with Satisfaction and physical Activity: A Cross-Sectional Study in 305 Dutch Participants. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Kates, A. Can the Affective Response to Exercise Predict Future Motives and Physical Activity Behavior? A Systematic Review of Published Evidence. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Zenko, Z.; Vazou, S. Do You Find Exercise Pleasant or Unpleasant? The Affective Exercise Experiences (AFFEXX) Questionnaire. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 55, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Sun, S.; Zickgraf, H.F.; Lin, Z.; Fan, X. Meta-Analysis of Gender Differences in Body Appreciation. Body Image 2020, 33, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.E.; Ullrich-French, S.; French, B.F. Validity Evidence for the State Mindfulness Scale for Physical Activity. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2016, 20, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.E.; McMahon, A.K. Exploring Changes in Mindfulness and Body Appreciation During Yoga Participation. Body Image 2019, 29, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Stock, N.M.; Alleva, J.M.; Jankowski, G.S.; Piran, N.; Riley, S.; Calogero, R.; Clarke, A.; Rumsey, N.; Slater, A.; et al. Looking to the Future: Priorities for Translating Research to Impact in the Field of Appearance and Body Image. Body Image 2020, 32, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleva, J.M.; Tylka, T.L.; van Oorsouw, K.; Montanaro, E.; Perey, I.; Bolle, C.; Boselie, J.; Peters, M.; Webb, J.B. The Effects of Yoga on Functionality Appreciation and Additional Facets of Positive Body Image. Body Image 2020, 34, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | 144 (72.0) |

| Women | 56 (28.0) | |

| Age, years | m (SD), range | 30.0 (9.4), 18–57 |

| Body mass index, categorical | Normal | 102 (51.0) |

| Overweight | 68 (34.0) | |

| Obese | 30 (15.0) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | m (SD), range | 25.5 (4.1), 17.6–41.5 |

| Involvement in sports, categorical | ≤2 years | 92 (46.0) |

| >2 years | 100 (50.0) | |

| Not specified | 8 (4.0) | |

| Involvement in sports, years | m (SD), range | 4.8 (6.1), 0.5–41.0 |

| Type of exercise attended | Resistance exercise | 125 (62.5) |

| Cardiovascular training | 55 (27.5) | |

| Functional and interval training | 20 (10.0) | |

| Study Measures | Involvement in Sports | BMI, kg/m2 | Mean | 95% CI | Effect of BMI, ŋ2, p | Effect of Involvement, ŋ2, p | Interaction BMI × Involvement, ŋ2, p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Body Appreciation Scale | ≤2 years | <25.0 | 3.70 | 3.45–3.95 | 0.12, <0.001 | 0.15, <0.001 | 0.03, 0.014 |

| ≥25.0 | 2.69 | 2.41–2.96 | |||||

| >2 years | <25.0 | 4.14 | 3.88–4.40 | ||||

| ≥25.0 | 3.78 | 3.53–4.04 | |||||

| OBCS: State Body Surveillance | ≤2 years | <25.0 | 3.08 | 2.67–3.49 | 0.06, <0.001 | 0.09, <0.001 | 0.01, 0.249 |

| ≥25.0 | 4.09 | 3.64–4.54 | |||||

| >2 years | <25.0 | 2.38 | 1.96–2.81 | ||||

| ≥25.0 | 2.90 | 2.49–3.31 | |||||

| SMS-PA-2: Monitoring Mind | ≤2 years | <25.0 | 3.33 | 3.08–3.59 | 0.01, 0.101 | 0.03, 0.012 | 0.00, 0.985 |

| ≥25.0 | 3.11 | 2.83–3.39 | |||||

| >2 years | <25.0 | 3.67 | 3.41–3.94 | ||||

| ≥25.0 | 3.45 | 3.20–3.71 | |||||

| SMS-PA-2: Monitoring Body | ≤2 years | <25.0 | 3.95 | 3.72–4.18 | 0.08, <0.001 | 0.07, <0.001 | 0.04, 0.006 |

| ≥25.0 | 3.14 | 2.89–3.39 | |||||

| >2 years | <25.0 | 4.08 | 3.84–4.32 | ||||

| ≥25.0 | 3.94 | 3.71–4.17 | |||||

| SMS-PA-2: Accepting Mind | ≤2 years | <25.0 | 3.08 | 2.81–3.35 | 0.03, 0.017 | 0.05, 0.004 | 0.03, 0.028 |

| ≥25.0 | 2.42 | 2.12–2.72 | |||||

| >2 years | <25.0 | 3.19 | 2.91–3.47 | ||||

| ≥25.0 | 3.16 | 2.89–3.43 | |||||

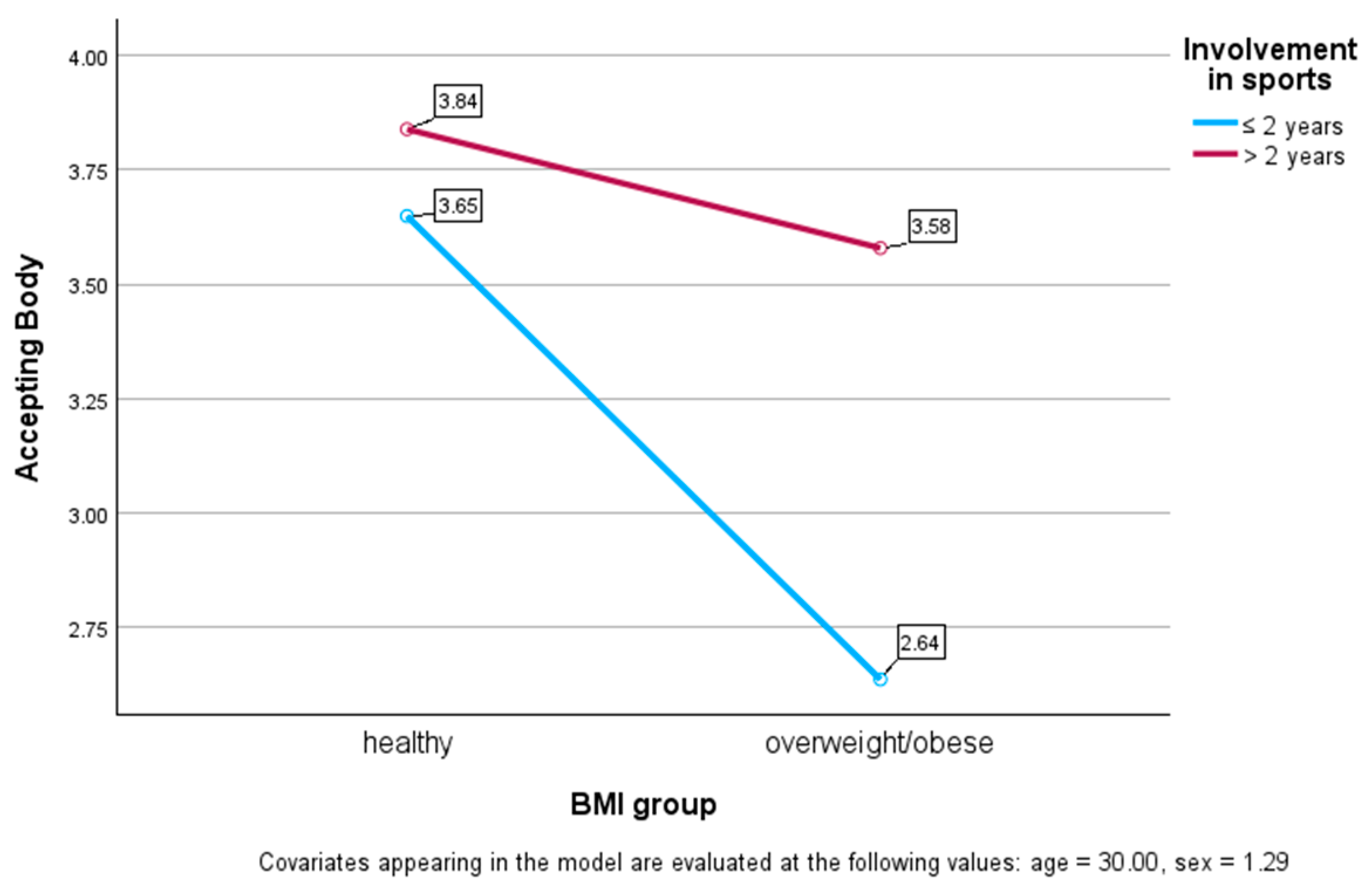

| SMS-PA-2: Accepting Body | ≤2 years | <25.0 | 3.65 | 3.36–3.94 | 0.09, <0.001 | 0.07, <0.001 | 0.03, 0.014 |

| ≥25.0 | 2.64 | 2.32–2.95 | |||||

| >2 years | <25.0 | 3.84 | 3.54–4.17 | ||||

| ≥25.0 | 3.58 | 3.29–3.87 | |||||

| State intrinsic exercise regulation | ≤2 years | <25.0 | 6.40 | 5.22–7.58 | 0.10, <0.001 | 0.10, <0.001 | 0.02, 0.035 |

| ≥25.0 | 2.27 | 0.97–3.57 | |||||

| >2 years | <25.0 | 7.90 | 6.67–9.13 | ||||

| ≥25.0 | 6.42 | 5.23–7.60 | |||||

| Pleasantness during exercise | ≤2 years | <25.0 | 4.11 | 3.84–4.37 | 0.08, <0.001 | 0.10, <0.001 | 0.04, 0.007 |

| ≥25.0 | 3.19 | 2.90–3.48 | |||||

| >2 years | <25.0 | 4.37 | 4.10–4.64 | ||||

| ≥25.0 | 4.20 | 3.94–4.46 |

| Study Measures | B | β | t | p | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||||

| Female sex | 0.25 | 0.11 | 1.46 | 0.147 | 1.18 |

| Age, years | 0.01 | 0.09 | 1.15 | 0.253 | 1.32 |

| Involvement in sports, years | 0.05 | 0.31 | 4.25 | <0.001 | 1.13 |

| Model summary: F = 10.03, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.14 | |||||

| Step 2 | |||||

| Female sex | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.74 | 0.460 | 1.24 |

| Age, years | 0.01 | 0.07 | 1.29 | 0.198 | 1.33 |

| Involvement in sports, years | 0.03 | 0.17 | 3.19 | 0.002 | 1.20 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | −0.06 | −0.22 | −4.33 | <0.001 | 1.08 |

| OBCS: State Body Surveillance | −0.41 | −0.62 | −11.98 | <0.001 | 1.17 |

| Model summary: F = 50.60, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.58, ∆R2 = 0.44, ∆p < 0.001 | |||||

| Step 3 | |||||

| Female sex | −0.11 | −0.05 | −0.91 | 0.366 | 1.36 |

| Age, years | 0.01 | 0.09 | 1.82 | 0.071 | 1.36 |

| Involvement in sports, years | 0.03 | 0.15 | 3.07 | 0.002 | 1.23 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | −0.04 | −0.16 | −3.52 | <0.001 | 1.12 |

| OBCS: State Body Surveillance | −0.27 | −0.41 | −7.24 | <0.001 | 1.72 |

| SMS-PA-2: Monitoring Mind | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.835 | 1.74 |

| SMS-PA-2: Monitoring Body | 0.15 | 0.12 | 1.94 | 0.054 | 2.13 |

| SMS-PA-2: Accepting Mind | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.932 | 1.82 |

| SMS-PA-2: Accepting Body | 0.26 | 0.27 | 3.77 | <0.001 | 2.78 |

| Model summary: F = 39.74, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.66, ∆R2 = 0.08, ∆p < 0.001 | |||||

| Step 4 | |||||

| Female sex | −0.10 | −0.04 | −0.86 | 0.390 | 1.37 |

| Age, years | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1.71 | 0.090 | 1.36 |

| Involvement in sports, years | 0.02 | 0.13 | 2.78 | 0.006 | 1.24 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | −0.03 | −0.12 | −2.82 | 0.005 | 1.15 |

| OBCS: State Body Surveillance | −0.23 | −0.35 | −6.52 | <0.001 | 1.81 |

| SMS-PA-2: Monitoring Mind | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.901 | 1.77 |

| SMS-PA-2: Monitoring Body | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.630 | 2.33 |

| SMS-PA-2: Accepting Mind | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.838 | 1.83 |

| SMS-PA-2: Accepting Body | 0.18 | 0.19 | 2.75 | 0.007 | 2.97 |

| State intrinsic exercise regulation | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1.90 | 0.059 | 2.70 |

| Pleasantness during exercise | 0.05 | 0.20 | 3.05 | 0.003 | 2.62 |

| Model summary: F = 39.48, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.71, ∆R2 = 0.05, ∆p < 0.001 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baceviciene, M.; Bliujute, K.; Jankauskiene, R. Analysis of Factors Contributing to State Body Appreciation during Exercise. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080690

Baceviciene M, Bliujute K, Jankauskiene R. Analysis of Factors Contributing to State Body Appreciation during Exercise. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):690. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080690

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaceviciene, Migle, Kristina Bliujute, and Rasa Jankauskiene. 2024. "Analysis of Factors Contributing to State Body Appreciation during Exercise" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080690

APA StyleBaceviciene, M., Bliujute, K., & Jankauskiene, R. (2024). Analysis of Factors Contributing to State Body Appreciation during Exercise. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080690