Why We Share: A Systematic Review of Knowledge-Sharing Intentions on Social Media

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Media as a Tool for Knowledge Sharing

1.2. Challenges in Knowledge Sharing on Social Media

1.3. Current Psychology

2. Methodology

2.1. Review Protocol

2.2. Formulation of the Study Question

2.3. Question Search Strategy

2.4. Quality Appraisal

2.5. Data Extraction and Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Journal Landscape

3.2. Research Method

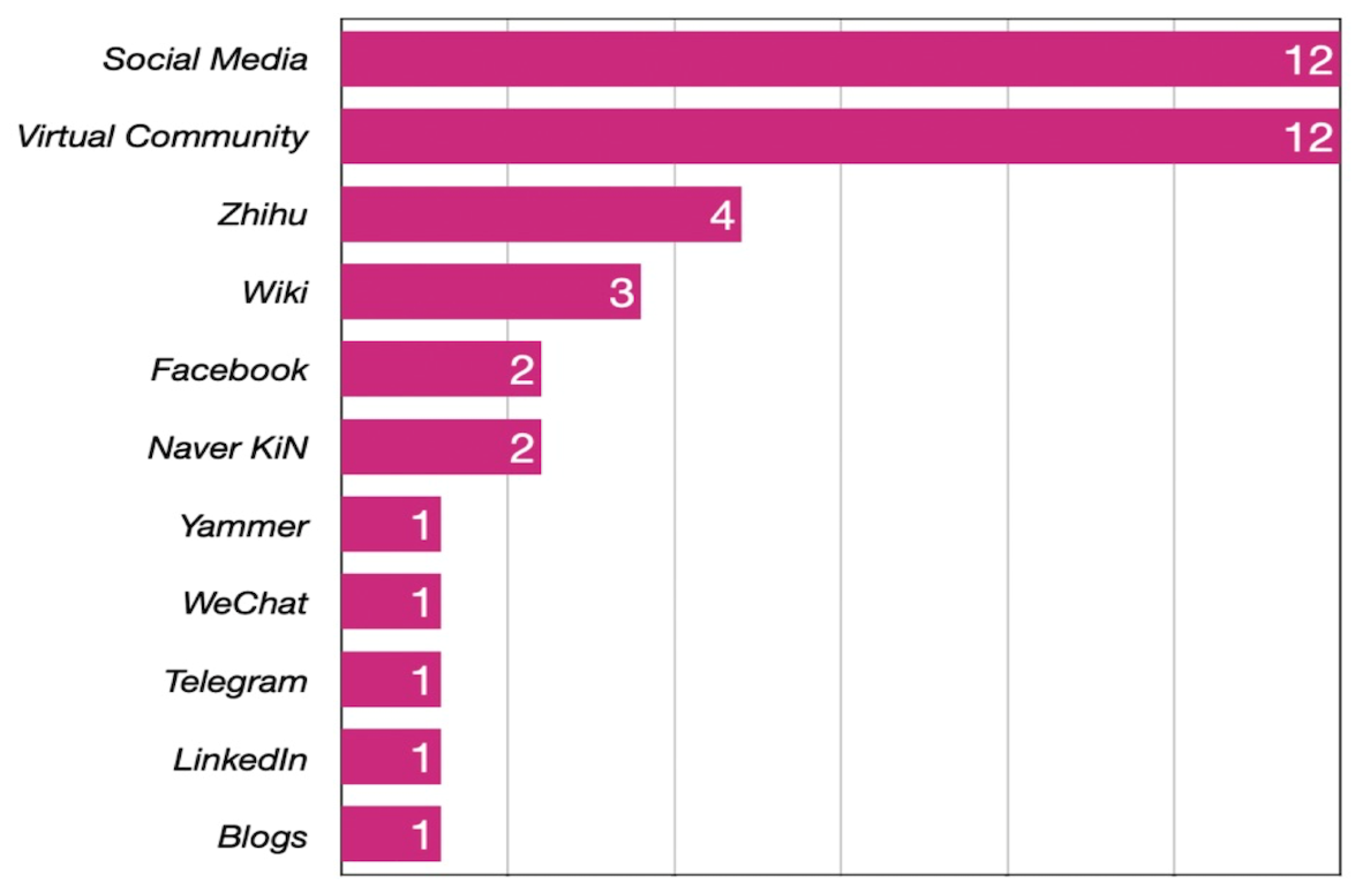

3.3. Usage of Social Media

3.4. Theories Lens

4. Conceptual Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Psychological Factors

5.2. Technology Factors

5.3. Environmental Factors

5.4. Social Factors

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Question Search Strategy

Appendix A.1. Stage 1: Identification

Appendix A.2. Stage 2: Screening

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Timeline | 2015–2023 | 2014 and earlier |

| Document type | Articles (with empirical data) | Books, article summaries, prefaces, interviews, news, reviews, etc. |

| Full-text acquisition | Full text available | Full text not available |

| Language | English | Non-English |

| Research objective | Directly answered the research question | Unrelated research purposes |

Appendix A.3. Stage 3: Eligibility

Appendix B. Quality Appraisal

| Study ID | RD | QA1 | QA2 | QA3 | QA4 | QA5 | NF | IR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [23] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [36] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [41] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [44] | QD | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [45] | QD | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [46] | QD | √ | X | √ | C | √ | 3/5 | √ |

| [58] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [59] | QD | √ | X | √ | X | √ | 3/5 | √ |

| [60] | QD | √ | X | √ | C | √ | 3/5 | √ |

| [61] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [62] | QD | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [63] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [64] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [65] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [66] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [67] | QD | √ | C | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [68] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [69] | QD | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [70] | QD | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [71] | MM | X | √ | √ | C | √ | 3/5 | √ |

| [72] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [73] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [74] | QD | √ | C | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [75] | QD | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [76] | QD | √ | X | √ | X | √ | 3/5 | √ |

| [77] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [78] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [79] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [80] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [81] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [82] | QD | √ | C | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [83] | QD | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [84] | QD | √ | X | √ | X | √ | 3/5 | √ |

| [85] | QD | √ | C | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [86] | QD | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [87] | QD | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [88] | QD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 5/5 | √ |

| [89] | MM | √ | √ | √ | C | √ | 4/5 | √ |

| [90] | QD | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | 4/5 | √ |

References

- Onyeagam, O.; Nwaki, W.; Obonadhuze, B.; Zakariyau, M. The Impact of Knowledge Management Practices on the Survival and Sustenance of Construction Organisations. CSID J. Infrastruct. Dev. 2020, 3, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilker, J. Data vs. Information vs. Knowledge: What Are The Differences? Available online: https://tettra.com/article/data-information-knowledge/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Oranga, J. Tacit Knowledge Transfer and Sharing: Characteristics and Benefits of Tacit & Explicit Knowledge. J. Account. Res. Util. Financ. Digit. Assets 2023, 2, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J.R. Tacit vs. Explicit Knowledge as Antecedents for Organizational Change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 1123–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, D.I.; Toulson, P. Is It Possible to Share Tacit Knowledge Using Information and Communication Technology Tools? Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2021, 70, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.P. Emerging Technologies: Factors Influencing Knowledge Sharing. World J. Educ. Res. 2022, 9, 68–74. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4066078 (accessed on 5 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.S.; Jian, Z.; Akram, U.; Akram, Z.; Tanveer, Y. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Team Creativity: The Roles of Team Psychological Safety and Knowledge Sharing. Pers. Rev. 2022, 51, 2404–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, I.; Khan, J.; Zada, M.; Zada, S.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Contreras-Barraza, N. Linking Ethical Leadership to Followers’ Knowledge Sharing: Mediating Role of Psychological Ownership and Moderating Role of Professional Commitment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 841590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.A.; Khurshid, M.M. Factors Impacting the Behavioral Intention to Use Social Media for Knowledge Sharing: Insights from Disaster Relief Practitioners. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 18, 269–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawnih, A.; Yaseen, H.; Al-Adwan, A.S.; Alsoud, R.; Jaber, O.A. Factors Influencing Social Media Adoption Among SMEs During COVID-19 Crisis. J. Manag. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2021, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Deng, Q.; Liu, W. Knowledge Sharing of Health Technology among Clinicians in Integrated Care System: The Role of Social Networks. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 926736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, P.; Liu, J.M.; Zhang, X.F. Achieving Popularity to Attract More Patients via Free Knowledge Sharing in the Online Health Community. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Dong, M. The Influence of Network Location on Knowledge Hiding from the Perspective of Lifelong Education. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 4881775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salimi, G.; Heidari, E.; Mehrvarz, M.; Safavi, A.A. Impact of Online Social Capital on Academic Performance: Exploring the Mediating Role of Online Knowledge Sharing. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 6599–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, S.; Andreu, L.; Campo, S. Knowledge Sharing Among Tourists via Social Media: A Comparison Between Facebook and TripAdvisor. Int. J. Tourism Res. 2017, 19, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, A.; Marine-Roig, E. Searching and Sharing of Information in Social Networks During the Different Stages of a Trip. Cuad. De Tur. 2018, 42, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, P.Y.; Evans, N.; Liu, C.Z.; Choo, K.-K.R. Understanding Factors Influencing Employees’ Consumptive and Contributive Use of Enterprise Social Networks. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 1357–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.S.; Ayambila, S.N.; Lukman, S. An Empirical Investigation of the Impact of Social Media Tool Usage on Employees Work Performance among Ghana Commercial Bank Workers: The Moderating Role of Social Media Usage Experience. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 20, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, S.; Taylor, C.R. Social Media and International Advertising: Theoretical Challenges and Future Directions. Int. Mark. Rev. 2013, 30, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidi, A.; Jusoh, Y.Y.; Abdullah, R.H.; Jabar, M.A.; Khalefa, M.S. Leveraging Social Media Technology for Uncovering Tacit Knowledge Sharing in an Organizational Context. In Proceedings of the 2015 9th Malaysian Software Engineering Conference (MySEC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 16–17 December 2015; pp. 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L.G.; Lee, J. Intrinsically Motivating Employees’ Online Knowledge Sharing: Understanding the Effects of Job Design. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichner, T.; Grünfelder, M.; Maurer, O.; Jegeni, D. Twenty-Five Years of Social Media: A Review of Social Media Applications and Definitions from 1994 to 2019. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzori, M.; Koutrika, G.; Pes, B.; Tanca, L. Special Issue on “Data Exploration in the Web 3.0 Age”. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 112, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, D.I.; Cuellar, S. Knowledge sharing and innovation: A systematic review. Knowl. Process Manag. 2020, 27, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R. Using data sciences in digital marketing: Framework, methods, and performance metrics. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Leng, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, K. A hierarchical blockchain-enabled federated learning algorithm for knowledge sharing in internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 3975–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayne. 13 Types of Social Media You Should Be Using in 2023; Invideo: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Petrosyan, A. Number of Internet and Social Media Users Worldwide as of January 2024; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, S.J. Daily Time Spent on Social Networking by Internet Users Worldwide from 2012 to 2023; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meltwater. DIGITAL 2023. In We Are Social & Meltwater; Meltwater: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Y.A.; Ahmad, M.N.; Ahmad, N.; Zakaria, N.H. Social media for knowledge-sharing: A systematic literature review. Telem. Inform. 2019, 37, 72–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamlath, S.; Wilson, T. Dimensions of student-to-student knowledge sharing in universities. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2022, 20, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.L.; Yan, X.; Tan, Y.; Sun, S.X. Shared Minds: How Patients Use Collaborative Information Sharing via Social Media Platforms. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2019, 28, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Gutiérrez, D.; Fernández-Betancort, H.; Santana-Talavera, A. Talking to Others: Analysing Tourists’ Communications on Cultural Heritage Experiences. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Barreda, A.; Okumus, F.; Nusair, K. Consumer Perception of Knowledge-Sharing in Travel-Related Online Social Networks. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-M. Four-Dimensional Model: A Literature Review in Online Organisational Knowledge Sharing. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2021, 51, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Khan, A.N. What Followers Are Saying about Transformational Leaders Fostering Employee Innovation via Organisational Learning, Knowledge Sharing and Social Media Use in Public Organisations? Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 101391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Hajli, M. Seeking and sharing health information on social media: A net valence model and cross-cultural comparison. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 126, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuori, V.; Okkonen, J. Knowledge sharing motivational factors of using an intra-organizational social media platform. J. Knowl. Manag. 2012, 16, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shi, W. A Predictive Model of the Knowledge-Sharing Intentions of Social Q&A Community Members: A Regression Tree Approach. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2022, 38, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Lin, C.; Qin, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhou, Z. Impact of monetary and non-monetary social functions on users’ knowledge-sharing intentions in online social Q&A communities. Internet Res. 2023, 33, 1422–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C. Exploring member’s knowledge sharing intention in online health communities: The effects of social support and overload. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Paul, J.; Sharma, R.R. The virality of advertising content. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 374–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, M. Cross-Cultural Examination of Music Sharing Intentions on Social Media: A Comparative Study in China and the United States. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Macura, B.; Whaley, P.; Pullin, A.S. ROSES Reporting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses: Pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ. Evid. 2018, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Samah, A.A.; Kamarudin, S. Speaking of the devil: A systematic literature review on community preparedness for earthquakes. Nat. Hazards 2021, 108, 2393–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, N.S.; Othman, A.; Nor, A.M. A Systematic Literature Review on the Development of Halal Tourism: Review Protocol Guided by Roses. Russ. Law J. 2023, 11, 2139–2153. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.H.; Hasan, N.A.; Muthokhir, A.R.; Pierewan, A.C. The Essential Characteristics of Knowledge Transfer Program: A review. Environ.-Behav. Proc. J. 2022, 7, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Krauss, S.E.; Samsuddin, S.F. A systematic review on Asian’s farmers’ adaptation practices towards climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemming, K.; Booth, A.; Garside, R.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Noyes, J. Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: Clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e000882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L.G. Community’s knowledge need and knowledge sharing in Wikipedia. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 912–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, B.; Sarrion, M.; Motiani, M.; O’Sullivan, S.; Chandwani, R. Exploration of factors affecting the use of Web 2.0 for knowledge sharing among healthcare professionals: An Indian perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 25, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Social media as a tool of knowledge sharing in academia: An empirical study using valance, instrumentality and expectancy (VIE) approach. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2531–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Malik, A.; Sharma, P. How to motivate employees to engage in online knowledge sharing? Differences between posters and lurkers. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 1811–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S. Understanding relationship commitment and continuous knowledge sharing in online health communities: A social exchange perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 26, 592–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.Z.; Barbera, E.; Rasool, S.F.; Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P.; Mohelská, H. Adoption of social media-based knowledge-sharing behaviour and authentic leadership development: Evidence from the educational sector of Pakistan during COVID-19. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. Active users’ knowledge-sharing continuance on social Q&A sites: Motivators and hygiene factors. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 70, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. Dual paths to continuous online knowledge sharing: A repetitive behavior perspective. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 72, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Oh, S.E. Individual characteristics influencing the sharing of knowledge on social networking services: Online identity, self-efficacy, and knowledge sharing intentions. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Shi, W. The influence of the community climate on users’ knowledge-sharing intention: The social cognitive theory perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 41, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.M.; Hsu, M.H.; Lee, Y.J. Factors Influencing Knowledge-Sharing Behavior in Virtual Communities: A Longitudinal Investigation. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2015, 32, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Pradas, S.; Hernández-García, Á.; Fernández-Cardador, P. Acceptance of corporate blogs for collaboration and knowledge sharing. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2017, 34, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, C.; Peng, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y. User willingness toward knowledge sharing in social networks. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.Y.M.; Tang, B.; Chau, K.W. Sustainable construction safety knowledge sharing: A partial least square-structural equation modeling and a feedforward neural network approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.Y.; Lai, H.M.; Chou, Y.C. Knowledge-sharing intention in professional virtual communities: A comparison between posters and lurkers. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 66, 2494–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, K.F.; Tan, F.B. The mediating role of trust and commitment on members’ continuous knowledge sharing intention: A commitment-trust theory perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Lai, M.C.; Yang, S.W. Factors influencing physicians’ knowledge sharing on web medical forums. Health Inf. J. 2016, 22, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.Y.; Lee, H.; Hovav, A. The effect of individual’s cultural values and social capital on knowledge sharing in web-based communication environment. J. Mod. Proj. Manag. 2016, 4, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.H. Developing an antecedent model of knowledge sharing intention in virtual communities. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2017, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Gong, Y. Social capital, motivations, and knowledge sharing intention in health Q&A communities. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1536–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, B. A glimpse into the virtual community of practice (CoP): Knowledge sharing in the Wikipedia community. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2018, 11, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Kwak, M.; Shin, S.K. A Calculus of Virtual Community Knowledge Intentions: Anonymity and Perceived Network-Structure. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2018, 58, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Guo, K. Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: A network perspective. Libr. Hi Tech. 2021, 39, 1174–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, A.; Baral, R. Enterprise social network (ESN) systems and knowledge sharing: What makes it work for users? VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2020, 50, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, M.; Saghafi, F.; Aghayi, E. A multidimensional model of knowledge sharing behavior in mobile social networks. Kybernetes. 2019, 48, 906–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemadi, R.; Hon, C.K.H.; Murphy, G.; Manley, K. The use of social media for work-related knowledge sharing by construction professionals. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2020, 16, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.A. Users’ intention to share knowledge using wiki in virtual learning community. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 2020, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-L.; Yin, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, X. The differential effects of trusting beliefs on social media users’ willingness to adopt and share health knowledge. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y. The Sustainability of Knowledge-Sharing Behavior Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior in Q&A Social Network Community. Complexity 2021, 2021, 1526199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Lan, Y.; Luo, X.; Li, H. The effect of commitment on knowledge sharing: An empirical study of virtual communities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Q.A.; Chen, J.V.; Nguyen, T.H.T. Continuance use of enterprise social network sites as knowledge sharing platform: Perspectives of tasks-technology fit and expectation disconfirmation theory. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. Stud. 2021, 12, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, N.; Kazemi, F.; Masoomi, E. Determinants of entrepreneurial knowledge and information sharing in professional virtual learning communities created using mobile messaging apps. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2021, 11, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Qaisar, N.; Kanwal, S. Factors affecting students’ knowledge sharing over social media and individual creativity: An empirical investigation in Pakistan. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QuickBooks, C.T. Understanding Consumer Behaviour: The Four Factors. Available online: https://quickbooks.intuit.com/ca/resources/marketing/four-factors-consumer-behaviormarketing/ (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Deng, H.; Duan, S.X.; Wibowo, S. Digital technology driven knowledge sharing for job performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 404–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausczik, Y.; Huang, X. Knowledge generation and sharing in online communities: Current trends and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Filieri, R.; Gorton, M. Continuance intention of online technologies: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 102315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reem, M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sara, N.R.W. Sustainability Indicators in Hotels: A Systematic Literature Review. Asia-Pac. J. Innov. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 11, 149–178. [Google Scholar]

- Clarivate. We Are the Web of Science. Available online: https://clarivate.com/products/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-workflow-solutions/webofscience-platform/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Dasí-Rodríguez, S. The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1023–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Journal | Total Number of Selected Articles (%) | Indexed by WoS | WoS Quartile | Indexed by Scopus | Scopus Quartile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of Knowledge Management | 6 (15%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| Aslib Journal of Information Management | 2 (5%) | √ | Q3 | √ | Q2 |

| Behavior and Information Technology | 2 (5%) | √ | Q2 | √ | Q1 |

| International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction | 2 (5%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| Information Systems Management | 2 (5%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| Sustainability | 2 (5%) | √ | Q2 | √ | Q1 |

| Architectural Engineering and Design Management | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q2 | √ | Q1 |

| Asian Journal of Business and Accounting | 1 (2.5%) | √ | - | √ | Q3 |

| Complexity | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q2 | √ | Q2 |

| Health Informatics Journal | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q3 | √ | Q2 |

| International Journal of Information Management | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management | 1 (2.5%) | - | - | √ | Q2 |

| Internet Research | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| International Journal of Knowledge Management Education | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies | 1 (2.5%) | √ | - | √ | Q3 |

| International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education | 1 (2.5%) | √ | - | √ | Q2 |

| Information Processing and Management | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| Journal of Computer Information Systems | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q3 | √ | Q1 |

| Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research | 1 (2.5%) | √ | - | - | - |

| Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q2 | √ | Q1 |

| Journal of Modern Project Management | 1 (2.5%) | - | - | √ | Q3 |

| Kybernetes | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q3 | √ | Q2 |

| Library Hi Tech | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q2 | √ | Q2 |

| Management Decision | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q3 | √ | Q1 |

| PLoS ONE | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q2 | √ | Q1 |

| Technological Forecasting and Social Change | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| Tourism Management | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q1 | √ | Q1 |

| Universal Access in the Information Society | 1 (2.5%) | √ | Q3 | √ | Q2 |

| VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems | 1 (2.5%) | - | - | √ | Q1 |

| Conceptual/Theoretical Framework | Study ID | No. |

|---|---|---|

| Theory of Planned Behavior 1 | [9,61,65,66,72,86] | 6 |

| Technology Acceptance Model 1 | [9,45,69,70,72] | 5 |

| Social Cognitive Theory 1 | [41,67,75,77] | 4 |

| Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motives 1 | [46,61,74,77] | 4 |

| Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 1 | [63,81,83,84] | 4 |

| Theory of Reasoned Action 1 | [59,65,90] | 3 |

| Task-Technology Fit Theory 1 | [88] | 1 |

| Expectation Confirmation Theory 1 | [65] | 1 |

| Information Systems Continuous Use Model 1 | [73] | 1 |

| Valance, Instrumentality and Expectancy 1 | [60] | 1 |

| Expectation Disconfirmation Theory 1 | [88] | 1 |

| Social Exchange Theory 2 | [59,62,74,87] | 4 |

| Commitment Trust Theory 2 | [62,73] | 2 |

| Commitment Model 2 | [87] | 1 |

| Social Identity Theory 2 | [66] | 1 |

| Social Influence Theory 2 | [76] | 1 |

| Stimulus–Organism–Response Framework 2 | [26] | 1 |

| Utility Interdependence 2 | [58] | 1 |

| Not utilizing a conceptual framework | [36,44,64,68,71,78,79,80,82,85] | 10 |

| Study ID | Key Issues | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| [9] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and interpersonal trust |

| [23] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Social capital and social identity |

| [36] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Belief in integrity and perceived ease of use |

| [41] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Enjoyment, fairness, identification, and reciprocity |

| [44] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Subjective well-being |

| [45] | Advertisement-sharing intention | Advertisement content likeability |

| [46] | Music-sharing intention | Perceived enjoyment, self-presentation, relationship development, social identity, social presence, face risk, and perceived total benefit |

| [58] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Community’s need for knowledge, foregone benefit of free riding, knowledge codification effort, and level of knowledge |

| [59] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Attitude |

| [60] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Importance of knowledge exchange, perceived usefulness of social media, and experience using social media |

| [61] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control |

| [62] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Relationship commitment |

| [63] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence |

| [64] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Satisfaction |

| [65] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Satisfaction |

| [66] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Personal online identity, web-specific self-efficacy, and knowledge-creating self-efficacy |

| [67] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Outcome expectations and community climate |

| [68] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Commitment, trust, and knowledge-sharing self-efficacy |

| [69] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Perceived usefulness, managerial support, and altruism |

| [70] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Trust |

| [71] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Leader membership exchange, perceived organisation support, Homan Proposition (Concern for others), and institutional factors |

| [72] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Attitude and perceived behavioral control |

| [73] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Affective commitment, satisfaction, and trust |

| [74] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Attitude |

| [75] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Social capital |

| [76] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Subjective norm, group norm, and social identity |

| [77] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation |

| [78] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Community trust and community identification |

| [79] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Virtual network connectivity |

| [80] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Community attachment |

| [81] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Performance expectancy and hedonic motivation |

| [82] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Trust, reciprocity, altruism, and reputation |

| [83] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Performance expectancy and self-efficacy |

| [84] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and attitude |

| [85] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Source credibility, content credibility, and institution-based trust |

| [86] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Material reward and self-efficacy |

| [87] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Affective commitment and normative commitment |

| [88] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Knowledge-related task–technology fit, satisfaction, and knowledge self-efficacy |

| [89] | Knowledge-sharing intention | Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use |

| [90] | Knowledge-sharing behavior | Attitude, subjective norms, and enjoyment in helping others |

| Psychological Factors | Study ID | No. |

|---|---|---|

| Trust | [9,68,70,73,78,82,85] | 7 |

| Attitude | [9,59,61,72,74,84,90] | 7 |

| Self-efficacy | [66,68,83,86,88] | 5 |

| Satisfaction | [64,65,73,88] | 4 |

| Commitment | [62,68,73,87] | 4 |

| Perceived behavioral control | [9,61,72] | 3 |

| Altruism 1 | [69,82,90] | 3 |

| Perceived enjoyment 1 | [41,46,81] | 3 |

| Identification 1 | [41,66] | 2 |

| Perceived benefit 1 | [46,58] | 2 |

| Intrinsic motivation 1 | [77] | 1 |

| Extrinsic motivation 1 | [77] | 1 |

| Reciprocity 1 | [82] | 1 |

| Belief in integrity 1 | [37] | 1 |

| Self-presentation 1 | [46] | 1 |

| Material reward 1 | [86] | 1 |

| Concern for others 1 | [71] | 1 |

| Relationship development 1 | [46] | 1 |

| Reputation 1 | [82] | 1 |

| Importance of knowledge exchange 2 | [60] | 1 |

| Level of knowledge 2 | [58] | 1 |

| Source credibility 2 | [85] | 1 |

| Content credibility 2 | [85] | 1 |

| Knowledge codification effort 2 | [58] | 1 |

| Advertisement content likeability 2 | [45] | 1 |

| Technology Factors | Study ID | No. |

|---|---|---|

| Performance expectancy | [63,67,81,83,84] | 5 |

| Perceived usefulness | [60,69,89] | 3 |

| Effort expectancy | [63,84] | 2 |

| Perceived ease of use | [36,89] | 2 |

| Knowledge-related task–technology fit | [88] | 1 |

| Virtual network connectivity | [79] | 1 |

| Face risk | [46] | 1 |

| Experience using social media | [60] | 1 |

| Environmental Factors | Study ID | No. |

|---|---|---|

| Group norm | [76] | 1 |

| Community climate | [67] | 1 |

| Community’s need for knowledge | [58] | 1 |

| Community identification | [78] | 1 |

| Community attachment | [80] | 1 |

| Institutional factors | [71] | 1 |

| Managerial support | [69] | 1 |

| Perceived organization support | [71] | 1 |

| Leader membership exchange | [71] | 1 |

| Fairness | [41] | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, J.; Noor, S.M. Why We Share: A Systematic Review of Knowledge-Sharing Intentions on Social Media. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080636

Hu J, Noor SM. Why We Share: A Systematic Review of Knowledge-Sharing Intentions on Social Media. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):636. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080636

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Jia, and Shuhaida Md Noor. 2024. "Why We Share: A Systematic Review of Knowledge-Sharing Intentions on Social Media" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080636

APA StyleHu, J., & Noor, S. M. (2024). Why We Share: A Systematic Review of Knowledge-Sharing Intentions on Social Media. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080636