1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) represents a neurodegenerative disease that impacts physical, cognitive, visual and sensory functioning. Neurological symptoms like numbness or tingling, weakness of the limbs, imbalance, spasticity and visual problems are frequently encountered. Along with these, patients often deal with urinary and intestinal dysfunctions, fatigue, cognitive impairment, and emotional distress. The prevalence of MS is estimated at 35.9 per 100,000, often occurring in comorbidity with emotional disorders such as depression and/or anxiety [

1]. Sad mood, fear, irritability, psychomotor agitation, apathy, muscle tension and sleeping problems, accompanied by worries and ruminations related to the uncertainty of the disease’s progression, denote specific psychological difficulties encountered by MS patients. These may result in a wide range of negative consequences such as repeated hospitalizations, suicidal ideation, polypharmacy, unemployment and poor quality of interpersonal relationships. The vicious circle of dysfunctionality is further amplified through engagement in unhealthy coping strategies like avoidance, isolation, alcohol consumption and treatment non-adherence [

2].

Based on its clinical manifestation, MS has several subtypes. Relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) represents the most frequent subtype, characterized by acute attacks followed by complete recovery and no progression between relapses. The main symptoms consist of vision problems, neuropathy, unpleasant skin sensations, mental and physical tiredness, executive function deficits, grief, worry, fear of disease progression and anxious and depressive symptoms. Over time, the majority of patients diagnosed with RRMS will develop the secondary progressive MS (SPMS) subtype. This transition is explained by the debilitating progression of neurological symptoms with or without attacks. In addition to these common symptoms, patients experience significant walking difficulties, bladder and bowel problems, increased fatigue, cognitive impairment, depression and anxiety, sleeping problems and interpersonal difficulties. Primary progression MS (PPMS) is described as the progression of clinical manifestations with minimal improvements from the illness’s onset, representing the rarest subtype [

3].

The co-occurrence of depression and anxiety is more frequent in patients with MS than in the general population [

4]. The prevalence of clinical depressive and anxiety symptoms in MS patients ranges between 25 and 35% and between 21 and 35%, respectively [

5,

6], predominantly impacting the female gender [

6]. Considering the subtypes of MS, the prevalence of depression and anxiety proved to be higher in progressive MS (PMS) (19.13% and 24.07%) as compared with the relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) type (15.78% and 21.40%) [

5].

The comorbidity between MS and major depressive disorder can be explained using the biopsychosocial model [

7]. In this regard, neurobiological factors, such as brain injuries, cortical atrophies, and the progressive loss of gray matter in the limbic basal ganglion structures could be associated with depression [

8,

9]. A correlation between depressive symptoms and the treatment of MS with interferon beta (INFβ), such as INFβ-1a or INFβ-1b, has also been established [

10]. Due to its immuno-modulatory properties, INFβ was the first disease modifying therapy used for treating RRMS with excellent results in reducing relapses and brain lesions, while also slowing down the disability [

11]. Throughout the disease’s course, the occurrence of depression and anxiety could also be influenced by several social factors including age, education, marital and employment status, perceived limited social support and the quality of relationships, in addition to MS-specific symptoms and progression [

12]. Specifically, the clinical picture characterized by fatigue and depression as main symptoms that are often interacting make it difficult to differentiate between these two conditions [

13]. The most frequently cited psychological determinants of depression are learned helplessness, self-esteem, cognitive distortions, attributional style, negative affective memory errors, dysfunctional attitudes and high stress levels [

14,

15]. Moreover, in correlation with depression, the duration of disability and prolonged illness are the main factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts, which occur with a higher frequency in MS patients than the general population [

16]. As far as it is known, there is an overlap between MS symptoms and depression and/or anxiety [

6]. In these circumstances, underdiagnosed depression and/or anxiety may reduce treatment compliance, worsening symptoms and disability and negatively impacting the general health status and quality of life [

17,

18].

The efficiency of different psychological interventions for reducing depressive and anxiety disorders was the subject of many studies conducted in this area. Therefore, alongside pharmacological treatments [

19], psychological interventions like psychoeducation, supportive listening, counseling, cognitive behavioral therapies, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy and internet-based problem-solving therapy are recommended due to their effectiveness in the treatment of depression and anxiety symptoms associated with MS [

20,

21]. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapies (CBTs) are among the most effective psychological interventions, presenting medium treatment effects on the reduction of psychopathology, relying on protocols between 5 and 12 sessions or more [

22]. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) represents a type of talking therapy developed by Aron T. Beck in the 1960s as a structured, collaborative, shot-term and present-focused approach for helping clients manage their problems by changing their unhelpful patterns of thinking and behaving. Since then, this therapy has been adapted to various disorders and specific populations through changing some of its characteristics, except for the theoretical model [

23]. Hence, over time, cognitive behavioral interventions proved to be effective in reducing depression and anxiety symptoms linked to medical conditions [

24,

25,

26].

Beck’s cognitive theory postulates that the emergence of negative emotions is not directly determined by external events but by the way in which that person thinks and interprets those events, through negative automatic thoughts (NATs). According to Beck’s cognitive theory, NATs represent evaluative patterns of thinking (e.g., “I am no good”; “My future is hopeless”) mostly occurring at a pre-conscious level, characterized by reality distortion and rigidity, which are directly responsible for the occurrence of dysfunctional emotions and unhelpful behaviors [

23]. In conjunction with NATs, dysfunctional attitudes, described as cognitive distortions and profound beliefs about the self and the world (e.g., “Asking for help is a sign of weakness”; “The world is a dangerous place”), are maladaptive psychological mechanisms that predict clinical symptoms of depression and anxiety [

27]. Likewise, irrational beliefs refer to a set of cognitive distortions and assumptions accountable for an inappropriate sense of reality, leading to dysfunctional negative emotions. These are described as “should” statements (e.g., “I must feel better”), personalization (e.g., ”Failing to keep my job is my fault”), dichotomous thinking (e.g., ”I am a failure because I ‘ve got sick”), overgeneralization (e.g., “All people are bad”). Therefore, these beliefs are divided into the following subtypes: demandingness, awfulizing/catastrophizing, self-downing/global evaluation and low frustration tolerance [

28]. In this regard, CBT uses a series of specific techniques for helping patients develop an adaptive response for different stressful life situations [

23]. Cognitive techniques like Socratic questions, cognitive restructuring, behavioral experiments, and behavioral techniques (behavioral activation, exposure, relaxation, problem solving) are used to increase one’s self-efficacy, control and functional attitude.

To date, a series of observational studies have identified positive correlations between depression, anxiety and dysfunctional psychological mechanisms in patients with MS [

15,

29]. However, there is insufficient evidence regarding the effect of CBT interventions on these dysfunctional psychological mechanisms.

Despite their positive outcomes on the mental health status of MS patients, CBT interventions have also presented shortcomings resulting in problematic accessibility or increased dropout rates in face-to-face interventions, given the difficulties related to mobility issues and other specific MS symptoms. These limitations have led to the development of several computerized CBT programs to facilitate the access of MS patients to psychological treatments [

30,

31]. However, following a generalized psychological program is often challenging for MS patients, since it is not developed to respond to their needs resulting from the interaction between disease symptoms and psychosocial factors. Also, the motivation to complete computerized modules is typically lower due to the therapist’s absence throughout the changing process. Thus, dropout rates are typically higher in computerized CBT programs in comparison with face-to-face CBT sessions [

32].

Ultra-brief psychological interventions represent an alternative to full-length treatments, compacting core CBT techniques in up to five sessions, aiming to maximize efficiency, while also reducing the treatment duration. A typical session lasts between 15 and 45 min, involving a partially guided or unguided format [

33]. A recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated that a guided ultra-brief treatment for depression and anxiety was equivalent to a standard-length treatment, leading to a significant decrease in depressive and anxiety symptoms at both post-test and 9-week follow-up assessments. In this study, the ultra-brief intervention consisted of an online lesson that could be accessed by participants throughout one month [

34]. Single-session interventions (SSIs) are a specific type of well-structured ultra-brief treatment consisting of a unique session for developing the necessary cognitive, emotional and behavioral skills to manage psychological difficulties [

35]. In a meta-analysis, Odgers et al. (2022) compared the efficiency of a single session to multi-session exposure for specific phobias, concluding that both approaches were equally effective. More than that, single-session exposure was found to be more time- and cost-effective [

36]. Therefore, CBT SSIs could serve as an alternative to classical and computerized CBT programs for treating depression and anxiety in MS, facilitating treatment access especially for those individuals who face serious mobility difficulties or live in areas with poor availability of mental health services, such as rural places. For example, at a 3-month assessment, an SSI using a group CBT program for pain management had comparable outcomes with an eight-session CBT intervention for reducing the intensity of pain catastrophizing, as well as depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with chronic pain conditions [

37].

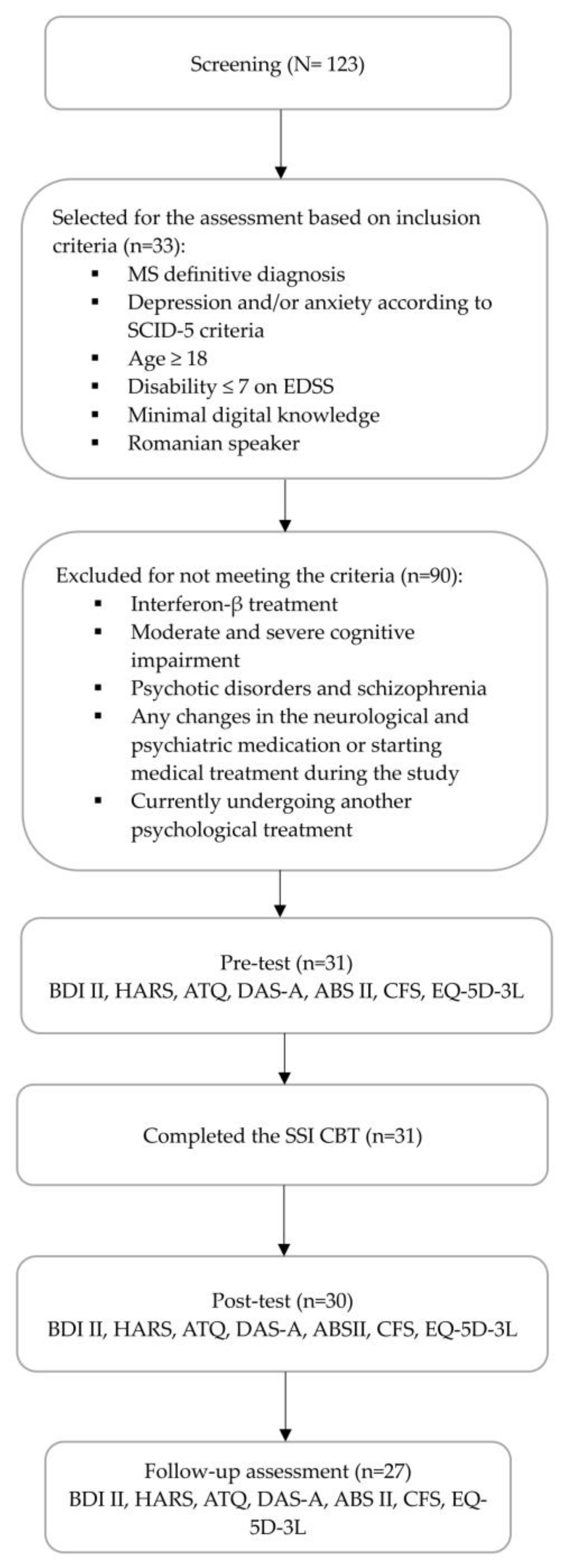

Attempts to identify the best approaches for improving physical and mental health, as well as overall quality of life, are ongoing in research on the effectiveness of psychological interventions for MS patients. In this context, the main goal of the present study is to test the effectiveness and feasibility of an online CBT SSI tailored to MS patients. In contrast to the common ultra-brief approach, the particularities of this intervention consist in the higher length of the session and permanent therapist guidance. The first hypothesis states that there are positive correlations between depression, anxiety and dysfunctional psychological mechanisms. The second hypothesis is that the CBT SSI would be associated with a substantial decrease in depression and anxiety. Moreover, there is a scarcity of studies exploring the effects of CBT beyond symptoms and focusing on the dysfunctional psychological mechanisms involved in the onset of depression and anxiety in patients with MS. For this reason, the third hypothesis of this study is that the CBT SSI would decrease irrational beliefs, NATs and dysfunctional attitudes as main dysfunctional psychological mechanisms. In addition, based on previous findings indicating a strong correlation between psychopathology and core MS symptoms, the fourth hypothesis of our research is that the CBT SSI would improve fatigue levels and perceived health status.

As far as we know, this is the first study investigating the impact of a psychological intervention on the reduction in dysfunctional psychological mechanisms in MS patients, reinforcing the role of these processes into the CBT framework.

3. Results

The sample included 31 MS patients with a mean age of 42.3 years (SD = 12.2). The percentage of females was 74.20% and the large majority, 90.30%, were diagnosed with RRMS. In the sample, 38.70% of the patients had minimal depression, 22,58% had mild depression, 25.80% scored for moderate depression and 12.90% were severely depressed. As for the intensity of anxiety symptoms, 9.67% presented mild intensity, 41.93% were moderately anxious and 48.39% of scores indicated moderate to severe levels of anxiety. Additionally, 41% of the patients were already retired, while 38.70% declared that they were employed. More than half of the patients were married. The sociodemographic and medical characteristics of participants included in this study are presented in

Table 1.

Table 2 presents the results of the correlation between variables indicating clinical symptoms and dysfunctional psychological mechanisms during the pre-test, post-test and follow-up assessments. All variables presented a normal distribution. Statistically significant positive correlations between symptom variables and all investigated psychological mechanisms were observed during the pre-test and follow-up assessments. Despite this, the correlations between anxiety and ABS II-DEM, ABS II-ach and DAS-A, as well as between depression and ABS II-DEM, ABS II- AWF and ABS II-ach were not statistically significant during post-test screening.

Table 3 illustrates the descriptive statistics and pairwise comparisons for all the variables of the pre-test mean with the means measured during post-test and follow-up screening. All variables were normally distributed at each of the three timepoints, with values for skewness falling in the −2–+2 interval and in the −7–+7 interval for kurtosis.

Table 4 presents the results from the post-test assessment. The table includes unstandardized regression estimates, confidence intervals, variance parameters for random effects and the proportion of variance explained by fixed effects (marginal r2) and by both random and fixed effects (conditional r2). The presented coefficients reflect results when controlling for covariates. We obtained a significant effect of time for all variables in the expected direction. Regarding the first objective, after the CBT SSI was implemented in our study, depressive B = −7.58, 95%CI (−12.84, −2.31),

p < 0.01 and anxiety symptoms B = −15.17 [−18.31, −12.02], with

p < 0.001 reduced from the pre-test to post-test period.

Table 5 presents the results from follow-up screening. From the pre-test to the follow-up period, both depression, with B = −8.08, 95%CI [−13.60, −2.56] and

p < 0.001, and anxiety symptoms, with B = −19.45, 95%CI [−22.88, −16.03] and

p < 0.001, were reduced, reaching the same statistical significance. The effects measured during the follow-up assessment were not significant for the variables ABS-DEM, ABS-SDG, ABS-LFT, ABS-re, ABS-ap, ABS-IR, DAS-A, ABS-R, DAS-A and CFS. The effect of time remained significant for all the other measures.

Table 6 presents the estimated marginal means. These results reflect the mean and the standard error estimated at the three timepoints when controlling for covariates.

Some effects of covariates and interactions between covariates and time were significant. These results are presented in

Table 7. For the purpose of conciseness, we report only the effects of covariates that were significant.

4. Discussion

The results of our study showed that an SSI based on CBT was efficient for improving the subjective health status of MS patients with mild to moderate anxiety and depression symptoms. These results are in accordance with previous studies highlighting an overall improvement in functional outcomes in chronic medical conditions following an SSI using a CBT framework [

71]. Also, this emphasizes that a brief intervention targeting the main difficulties of MS patients might resemble the effects of full-length CBT protocols in this specific population.

Regarding the first hypothesis, a significant correlation between depression, anxiety, NATs, irrational beliefs and dysfunctional attitudes was observed for all measurements. In other words, the reduction in dysfunctional psychological mechanisms is directly linked to a decrease in depressive and anxiety symptoms. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have identified the same correspondence between emotional distress and dysfunctional psychological mechanisms [

15,

29,

72,

73]. Moreover, some of these studies demonstrated the moderating effects of dysfunctional attitudes in the relation between negative life events and depression, as well as the mediating effect of NATs on depressive and anxiety symptoms [

72]. Likewise, Batmaz (2015) highlighted the predictive role of dysfunctional attitudes in the recurrence of MDD episodes [

74]. During post-test screening, the positive correlations between dysfunctional attitudes, NATs and depressive symptoms were preserved. We consider this to be justified through the lens of previous investigations that underlined the central role of NATs and dysfunctional attitudes in the onset of depression [

55]. Also, secondary irrational beliefs like self-downing/global evaluation and low frustration tolerance were particularly associated with depressive thoughts [

55,

73]; therefore, the expected relationship with depressive symptoms was maintained. Furthermore, the interaction between NATs and anxiety during the post-test assessment was maintained, as expected. Indeed, these psychological mechanisms were found to mediate anxiety symptoms. At the same time, the predictive role of dysfunctional attitudes was not significant for anxiety [

75,

76]. On the other hand, awfulizing and low frustration tolerance as irrational beliefs were associated with anxiety in particular [

55]. We believe this justifies the maintenance of correlations. In contrast, we consider that the absence of statistically significant correlations between demandingness, irrational beliefs, depression and anxiety could be understood through the nature of anxiety and depression in MS, which should be explored in further studies. Nevertheless, the correlations obtained between the follow-up measurements could be explained by the lasting effects of practicing the cognitive and behavioral techniques established in the action plan during the SSI, along with other contextual factors that were not assessed. Therefore, we assume that the routine evaluation of dysfunctional psychological mechanisms, along with the assessment of clinical symptoms, would be beneficial for preventing the onset of clinical distress.

As for the second hypothesis, the CBT SSI implemented in our study was efficient in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms. These results are aligned with the literature on the benefits of brief CBT interventions for alleviating depression and anxiety symptoms in chronic diseases [

37,

77]. Moreover, this outcome was preserved from the post-test assessment to the follow-up screening, in terms of both depression and anxiety. In the same way, past analyses underlined the lasting positive effects of short CBT interventions for psychological adjustment [

37,

78]. A strength of our investigation was the use of both self-reports and clinician-rated instruments for the assessment of psychopathology, indicating similar results at both temporal points. In our opinion, the observed benefits could be related to the integrative nature of the intervention that combined cognitive and behavioral techniques, adapting them to the specificity of MS. Also, using psychoeducation is known to improve the clinical picture in patients with chronic medical conditions.

The third hypothesis of our study regarding the involvement of dysfunctional psychological mechanisms in depression and/or anxiety was only partially confirmed. In this respect, we noticed that irrational beliefs were reduced after the CBT SSI. More specifically, the level of irrational beliefs decreased when measured during the both post-test and follow-up screenings. These results can be explained through the fact that the CBT SSI only addressed “cold cognitions”, which are generally considered a type of surface-level thinking [

79].

Interestingly, although the intensity of NATs remained unmodified in terms of the post-test screening, it reduced significantly during the follow-up period. We consider that this discrepancy related to the intensity of NATs between the two assessments could be the result of the patients’ willingness to follow the personalized action plan consisting of cognitive, behavioral and mindfulness techniques until the follow-up assessment.

Another explanation could be attributed to NATs’ description as “hot cognitions” (i.e., evaluative, less conscious, unmotivating and mostly negative thoughts) that trigger and exacerbate emotional, behavioral and physiological dysfunctional reactions. Therefore, the identification and modification of NATs’ contents and significations require a longer duration for the development of a more adaptative behavioral response to internal and external events [

23,

80]. Our results are consistent with the study of Troeung et al. (2014), observing a statistically significant reduction in negative thinking related to depression and anxiety disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease after adjusting a CBT protocol to the specific nature of this condition [

81]. Another possible explanation is the integrative nature of the protocol, which incorporated mindfulness and CBT techniques guiding patients to become more self-efficient and self-controlled in accepting and tolerating negative emotions in order to cope with the disease’s course [

82]. Moreover, among the therapeutic processes involved throughout the session for alleviating symptom intensity, we have mentioned cognitive restructuring, emotion regulation, collaboration and the action plan [

83]. Likewise, studies on the mechanisms/processes of action in CBT have outlined the role of the cognitive dimension for facilitating change in these approaches [

84,

85]. At the same time, the NAT level was influenced by the interactive effects between the intervention and degree of cognitive impairment. These results reinforce the idea that the negative thinking styles found in depression and anxiety positively correlate with memory, information processing and executive functioning deficits in MS [

86].

Dysfunctional attitudes are the only mechanisms that did not decrease after the CBT SSI. We consider that challenging dysfunctional attitudes would require multiple psychotherapeutic sessions, together with other specific cognitive behavioral strategies, since they constitute the core beliefs of the cognitive triad.

Concerning the fourth hypothesis, the positive effect of the intervention on health alone has been confirmed. This finding stresses the role of cognitive and behavioral techniques for lifestyle change, facilitating physical and mental wellbeing in MS patients. In terms of perceived health, several quality-of-life components increased, including mobility, engaging in daily activities, self-care, lack of pain and psychological well-being. This is in accordance with other studies that proved the importance of CBT in the clinical management of long-term medical conditions [

87]. In line with previous investigations, disability scores predicted the intervention’s impact on aspects related to quality of life in patients with MS [

88].

In contrast to findings regarding previous CBT protocols that were associated with a decrease in fatigue levels as a result of emotional distress alleviation, our intervention did not achieve the same outcome. An explanation could be related to the shortness of our intervention. For example, a meta-analysis conducted by Van der Akker et al. (2016) showed that although the level of fatigue improved in MS patients who pursued a CBT intervention consisting of four to eight sessions, the fatigue level started to increase shortly after the end of the psychotherapeutic process [

89]. Another argument relies on the multifactorial origin of fatigue in MS, which points to the necessity of diverse interventional approaches [

90].

Moreover, the findings of the present study could be influenced by the characteristics of the intervention provider. Possibly, expertise in the field of clinical work could facilitate protocol adjustment to aid the patients’ response to the psychological treatment. As a future direction, upcoming investigations could test the impact of the same protocol applied by therapists with different degrees of expertise.

Nonetheless, beyond the outcomes, this pilot study involves some limitations. One of the main constraints was related to the lack of a control group, which hinders the interpretability of the positive results obtained in this research. For this reason, comparisons between the effects of different protocol components and other confounds could not be performed. Another limitation is the small sample size, which does not allow the extrapolation of our findings to the entire population in the target group. Additionally, these results can be attributed only to the specific patient group included in our study, specifically to the RRMS type of MS, which represented the majority of our sample. Also, due to specific MS symptomatology, the length of the protocol could be demanding within a digital environment. Therefore, future studies could test the protocol in a face-to-face format. A limitation of the present protocol is that the cognitive strategies focused predominately on NATs and less on dysfunctional attitudes, given the brief duration of the intervention. Given the impossibility to address higher-order dysfunctional cognitive mechanisms and exposure techniques that particularly target anxiety disorders in a unique session, we assume that the SSI is feasible only for mild to moderate depressive and anxiety symptoms, which were present in our group. An important direction for future research would be to assess the benefits of this SSI CBT including a passive and active control group within rigorously conducted randomized controlled trials. This would allow for the comparative evaluation of different change mechanisms as a function of different covariates, permitting the development of a more personalized approach. Moreover, a larger sample size would be required for extrapolating the positive outcome of the SSI CBT with greater confidence. In addition, more studies analyzing the role of each intervention component for patients with specific MS characteristics would be necessary. Likewise, a larger diversity of cognitive techniques could increase the effectiveness of the SSI.

Clinical Implications

The protocol in the present study can be applied especially for MS patients with limited access to mental health services as a consequence of their socio-economic background and several demographic factors. Also, the use of brief CBT for reducing anxiety, depression and associated dysfunctional psychological mechanisms may promote compliance with medical treatments, ultimately improving the overall health status. At the same time, the action plan can serve as a useful tool for consolidating the skills acquired during the session. Furthermore, besides its application in ambulatory encounters, this digital intervention could be adapted for in-patient contexts, integrating this protocol within the standard treatment applied during hospitalization periods. A positive feature of the SSI is that it can be implemented by trained medical staff to improve the general care of MS patients as part of a holistic approach for preventing the development and exacerbation of psychopathology.