The Effects of Illegitimate Tasks on Task Crafting and Cyberloafing: The Role of Stress Mindset and Stress Appraisal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Interactive Effects of Illegitimate Tasks and Stress Mindset on Cognitive Appraisal

2.2. Primary Appraisals and Secondary Appraisals

2.3. Moderated Mediating Effects

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3. Testing the Hypotheses

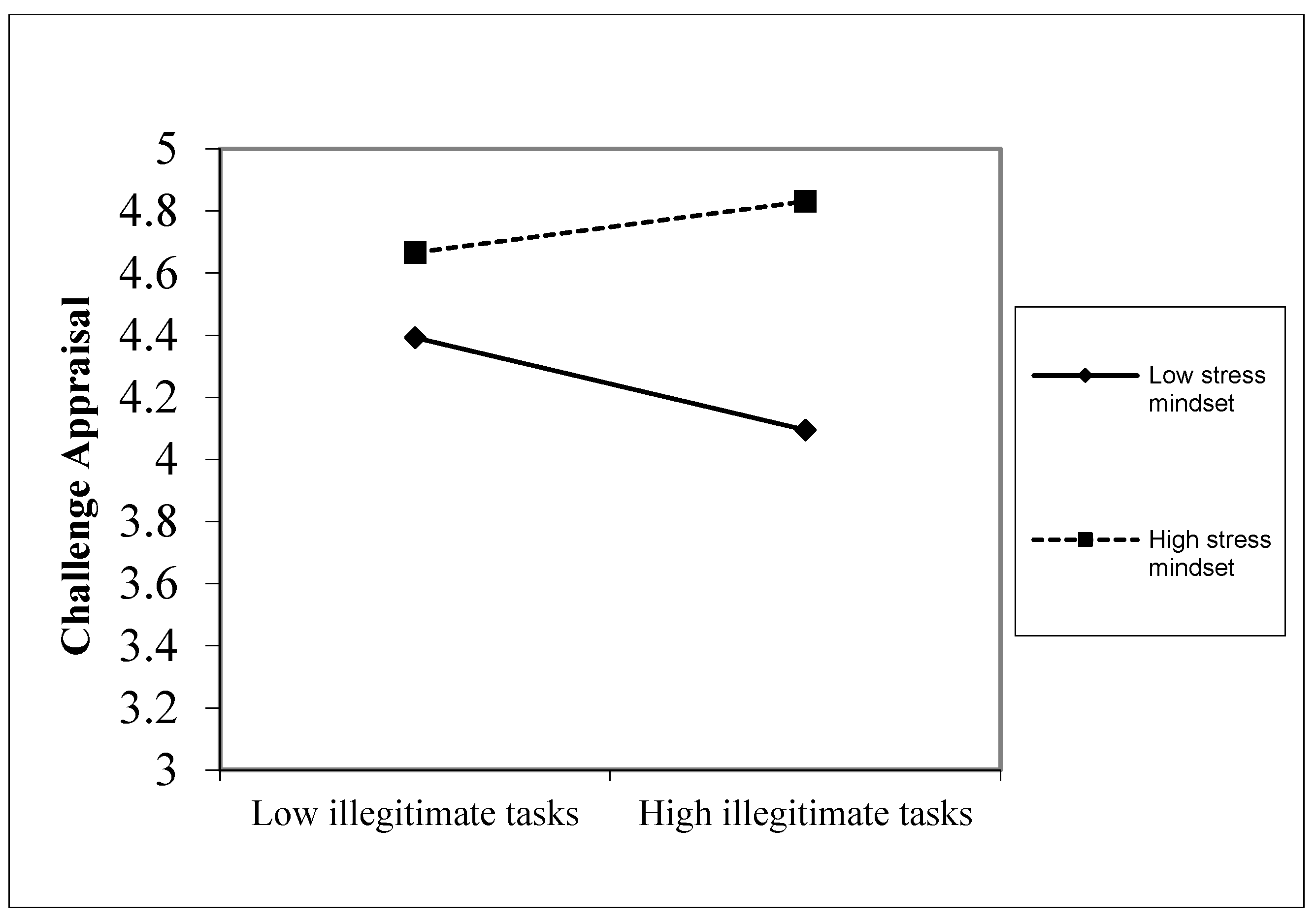

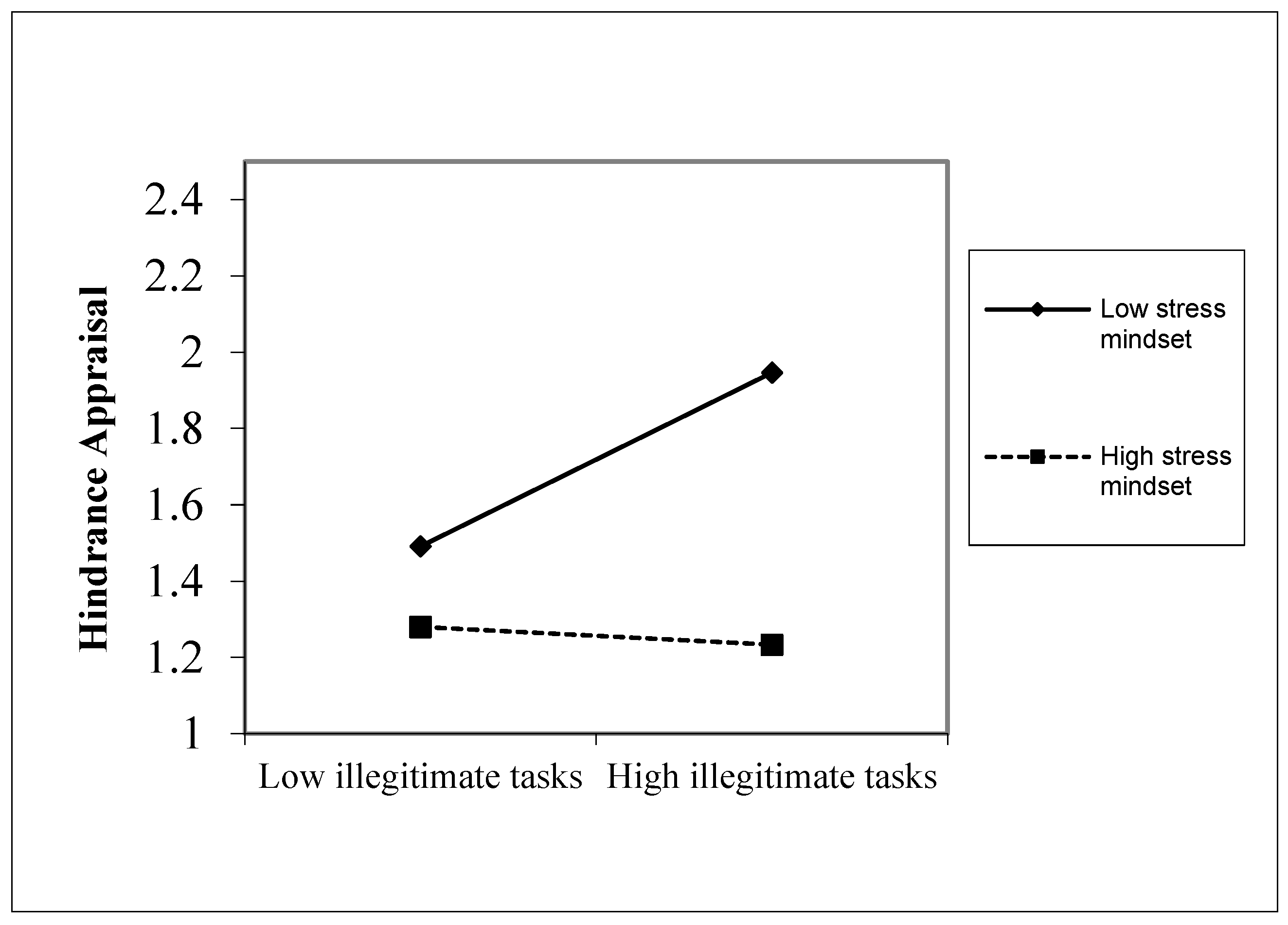

4.3.1. Moderating Effects

4.3.2. Direct Effects Test

4.3.3. Moderated Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement

| Scales | Items |

|---|---|

| The Bern Illegitimate Task Scale [7] | Unreasonable tasks: Do you have work tasks to take care of which you believe … 1. … should be done by someone else? 2. … are going too far and should not be expected from you? 3. …put you into an awkward position? 4. …are unfairly required of you? Unnecessary tasks: Do you have work tasks to take care of which keep you wondering if… 5. …they have to be done at all? 6. … they would not exist (or could be done with less effort), if things were organized differently? 7. …they make sense at all? 8. …they just exist because some people simply demand to have it this way? |

| Stress Mindset Measure [13] | 1. The effects of stress are negative and should be avoided. (Reverse) 2. Experiencing stress facilitates my learning and growth. 3. Experiencing stress depletes my health and vitality. (Reverse) 4. Experiencing stress enhances my performance and productivity. 5. Experiencing stress inhibits my learning and growth. (Reverse) 6. Experiencing stress improves my health and vitality. 7. Experiencing stress debilitates my performance and productivity. (Reverse) 8. The effects of stress are positive and should be utilized. |

| Challenge appraisal [40] | Challenge appraisal: 1. Working to fulfill the demands of my job helps to improve my personal growth and well-being. 2. I feel the demands of my job challenge me to achieve personal goals and accomplishment. 3. In general, I feel that my job promotes my personal accomplishment. Hindrance appraisal: |

| Hindrance appraisal [40] | 1. Working to fulfill the demands of my job thwarts my personal growth and well-being. 2. I feel the demands of my job constrain my achievement of personal goals and development. 3. In general, I feel that my job hinders my personal accomplishment. |

| Task crafting [59] | 1. You introduce new approaches to improve your work. 2. You change the scope or types of tasks that you complete at work. 3. You introduce new work tasks that you think better suit your skills or interests. 4. You choose to take on additional tasks at work. 5. You give preference to work tasks that suit your skills or interests. |

| Cyberloafing [60] | I use the internet at work to… 1. Visit websites and digital newspapers to seek personal information. 2. Download software or files for personal or family use. 3. Visit the website of my bank to consult my current account. 4. Read or send personal (non-professional) emails. 5. Surf the net and so escape a little. |

References

- Semmer, N.K.; Jacobshagen, N.; Meier, L.L.; Elfering, A. Occupational stress research: The Stress-As-Offense-To-Self Perspective. In Occupational Health Psychology: European Perspectives on Research, Education and Practice; McIntyre, S., Houdmont, J., Eds.; Nottingham University Press: Nottingham, UK, 2007; Volume 2, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Semmer, N.K.; Jacobshagen, N.; Meier, L.L.; Elfering, A.; Beehr, T.A.; Kaelin, W.; Tschan, F. Illegitimate tasks as a source of work stress. Work Stress 2015, 29, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Kuvaas, B. Illegitimate tasks: A systematic literature review and agenda for future research. Work Stress 2023, 37, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, E.M.; Meier, L.L.; Igic, I.; Elfering, A.; Spector, P.E.; Semmer, N.K. You want me to do what? Two daily diary studies of illegitimate tasks and employee well-being. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Zhang, H.; Yang, S.; Yu, Z.; Guo, M. Do Illegitimate Tasks Lead to Work Withdrawal Behavior among Generation Z Employees in China? The Role of Perceived Insider Status and Overqualification. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Peng, Y. The performance costs of illegitimate tasks: The role of job identity and flexible role orientation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 100, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N.K.; Tschan, F.; Meier, L.L.; Facchin, S.; Jacobshagen, N. Illegitimate Tasks and Counterproductive Work Behavior. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 59, 70–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, F. It is not only what you do, but why you do it: The role of attribution in employees? Emotional and behavioral responses to illegitimate tasks. J. Vocat. Behav. 2023, 142, 103860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G.; Wang, H.-J. Ethical human resource management mitigates the positive association between illegitimate tasks and employee unethical behaviour. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, L.L.; Semmer, N.K. Illegitimate tasks as assessed by incumbents and supervisors: Converging only modestly but predicting strain as assessed by incumbents, supervisors, and partners. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, J.R.; Beehr, T.A.; Love, K. Extending the challenge-hindrance model of occupational stress: The role of appraisal. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, A.J.; Salovey, P.; Achor, S. Rethinking Stress: The Role of Mindsets in Determining the Stress Response. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 716–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casper, A.; Sonnentag, S.; Tremmel, S. Mindset matters: The role of employees’ stress mindset for day-specific reactions to workload anticipation. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 798–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hajj, R.; Vongas, J.G.; Jamal, M.; ElMelegy, A.R. The essential impact of stress appraisals on work engagement. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, W.; Fu, M. Promoting or Prohibiting? Investigating How Time Pressure Influences Innovative Behavior under Stress-Mindset Conditions. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, H.; Gao, R.; Teng, R.; Zhao, J.; Yue, L.; Li, F.; Liao, Q. The costs and opportunities of overload: Exploring the double-edged sword effect of unreasonable tasks on thriving at work. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 13742–13756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Freiburger, K.J.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Rosen, C.C. Laying the Foundation for the Challenge–Hindrance Stressor Framework 2.0. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 165–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, N.K.; Tschan, F.; Jacobshagen, N.; Beehr, T.A.; Elfering, A.; Kaelin, W.; Meier, L.L. Stress as Offense to Self: A Promising Approach Comes of Age. Occup. Health Sci. 2019, 3, 205–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.S.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Vogel, R.M.; Mawritz, M.B.; Keating, D.J. Can You Handle the Pressure? The Effect of Performance Pressure on Stress Appraisals, Self-Regulation, and Behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepine, J.A.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Lepine, M.A. A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor-hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilby, C.J.; Sherman, K.A.; Wuthrich, V. Towards understanding interindividual differences in stressor appraisals: A systematic review. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 135, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hou, L. An Actor-Partner Interdependence Model of Work Challenge Stressors and Work-Family Outcomes: The Moderating Roles of Dual-Career Couples’ Stress Mindsets. J. Bus. Psychol. 2021, 36, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, J.J.; Disselhorst, R. Should we be “challenging” employees?: A critical review and meta-analysis of the challenge-hindrance model of stress. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Shin, K.; Hwang, J. Too much may be a bad thing: The difference between challenge and hindrance job demands. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 6180–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Palmer, J.C.; Halliday, C.S.; Blass, F.R. The role of stress mindsets and coping in improving the personal growth, engagement, and health of small business owners. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 1310–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, J.P.; Crum, A.J.; Goyer, J.P.; Marotta, M.E.; Akinola, M. Optimizing stress responses with reappraisal and mindset interventions: An integrated model. Anxiety Stress Coping 2018, 31, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntz, J.; Dormann, C.; Kronenwett, M. Supervisors’ relational transparency moderates effects among employees’ illegitimate tasks and job dissatisfaction: A four-wave panel study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minei, E.M.; Eatough, E.M.; Cohen-Charash, Y. Managing Illegitimate Task Requests Through Explanation and Acknowledgment: A Discursive Leadership Approach. Manag. Commun. Q. 2018, 32, 374–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebschmann, N.A.; Sheets, E.S. The right mindset: Stress mindset moderates the association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. Anxiety Stress Coping 2020, 33, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Braucks, J.; Baethge, A.; Dormann, C.; Vahle-Hinz, T. Get Even and Feel Good? Moderating Effects of Justice Sensitivity and Counterproductive Work Behavior on the Relationship between Illegitimate Tasks and Self-Esteem. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Connor-Smith, J. Personality and Coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing Coping Strategies—A Theoretically Based Approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor-Smith, J.K.; Flachsbart, C. Relations between personality and coping: A meta-analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 1080–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliese, P.D.; Edwards, J.R.; Sonnentag, S. Stress and Well-Being at Work: A Century of Empirical Trends Reflecting Theoretical and Societal Influences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searle, B.J.; Auton, J.C. The merits of measuring challenge and hindrance appraisals. Anxiety Stress Coping 2015, 28, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, H. Stressors and Stressor Appraisals: The Moderating Effect of Task Efficacy. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S.; Fritz, C. Work characteristics, challenge appraisal, creativity, and proactive behavior: A multi-level study. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espedido, A.; Searle, B.J. Proactivity, stress appraisals, and problem-solving: A cross-level moderated mediation model. Work Stress 2021, 35, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Crawford, E.R.; Rich, B.L. Turning Their Pain to Gain: Charismatic Leader Influence on Follower Stress Appraisal and Job Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1036–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Bindl, U.K.; Strauss, K. Making Things Happen: A Model of Proactive Motivation. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.L.; Bell, K.; Gagne, M.; Carey, K.; Hilpert, T. Collateral damage associated with performance-based pay: The role of stress appraisals. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hooff, M.L.M.; van Hooft, E.A.J. Dealing with daily boredom at work: Does self-control explain who engages in distractive behaviour or job crafting as a coping mechanism? Work Stress 2023, 37, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Lin, H.; Kong, Y. Challenge or hindrance? How and when organizational artificial intelligence adoption influences employee job crafting. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 113987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Teng, R.; Song, J. Linking employees’ challenge-hindrance appraisals toward AI to service performance: The influences of job crafting, job insecurity and AI knowledge. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 975–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J.D.; Perrewe, P.L. The AAA (appraisals, attributions, adaptation) model of job stress: The critical role of self-regulation. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 4, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrewé, P.L.; Zellars, K.L. An examination of attributions and emotions in the transactional approach to the organizational stress process. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Huang, Y.; Bodla, A.A.; Zou, X. The Interactive Effect of Stressor Appraisals and Personal Traits on Employees? Procrastination Behavior: The Conservation of Resources Perspective. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 781–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askew, K.; Buckner, J.E.; Taing, M.U.; Ilie, A.; Bauer, J.A.; Coovert, M.D. Explaining cyberloafing: The role of the theory of planned behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V.K.G. The IT way of loafing on the job: Cyberloafing, neutralizing and organizational justice. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaz, A.; Sheikh, A. Cyberloafing and job burnout: An investigation in the knowledge-intensive sector. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindek, S.; Krajcevska, A.; Spector, P.E. Cyberloafing as a coping mechanism: Dealing with workplace boredom. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anden, S.A.; Kessler, S.R.; Pindek, S.; Kleinman, G.; Spector, P.E. Is cyberloafing more complex than we originally thought? Cyberloafing as a coping response to workplace aggression exposure. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Nie, Q.; Chen, X. Managing hospitality employee cyberloafing: The role of empowering leadership. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 108, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, Y.; Hai, M.; Wang, W.; Niu, B. Challenge-hindrance stressors and cyberloafing: A perspective of resource conservation versus resource acquisition. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Mei, W.; Liu, L.; Ugrin, J.C. The bright and dark sides of social cyberloafing: Effects on employee mental health in China. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Slemp, G.R.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. The job crafting questionnaire: A new scale to measure the extent to which employees engage in job crafting. Int. J. Wellbeing 2013, 3, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P.; Verano-Tacoronte, D.; Ding, J.-M.T. Do current anti-cyberloafing disciplinary practices have a replica in research findings? A study of the effects of coercive strategies on workplace Internet misuse. Internet Res. 2006, 16, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- David, E.M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Farh, J.-L.; Lin, X.; Zhou, F. Is ‘be yourself’ always the best advice? The moderating effect of team ethical climate and the mediating effects of vigor and demand-ability fit. Hum. Relat. 2021, 74, 437–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntz, J.; Dormann, C. Moderating effects of appreciation on relationships between illegitimate tasks and intrinsic motivation: A two-wave shortitudinal study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2020, 29, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindek, S.; Demircioglu, E.; Howard, D.J.; Eatough, E.M.; Spector, P.E. Illegitimate tasks are not created equal: Examining the effects of attributions on unreasonable and unnecessary tasks. Work Stress 2019, 33, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostel, E.; Syrek, C.J.; Antoni, C.H. Turnover Intention as a Response to Illegitimate Tasks: The Moderating Role of Appreciative Leadership. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2018, 25, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Toich, M.J.; Ozkum, S.B. Trait Activation Theory: A Review of the Literature and Applications to Five Lines of Personality Dynamics Research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2021, 8, 199–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makikangas, A.; Minkkinen, J.; Muotka, J.; Mauno, S. Illegitimate tasks, job crafting and their longitudinal relationships with meaning of work. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 1330–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, Z. Craft it if you cannot avoid it: Job crafting alleviates the detrimental effects of illegitimate tasks on employee health. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 7924–7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Parker, S.K. Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.E.; Eatough, E.M.; Wald, D.R. Feeling insulted? Examining end-of-work anger as a mediator in the relationship between daily illegitimate tasks and next-day CWB. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lam, L.W.; Zhu, J.N.Y.; Zhao, S. Doing It Purposely? Mediation of moral Disengagement in the Relationship between Illegitimate Tasks and Counterproductive Work Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 179, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, D.S.; Bryan, C.J.; Gross, J.J.; Murray, J.S.; Krettek Cobb, D.; Santos, P.H.F.; Gravelding, H.; Johnson, M.; Jamieson, J.P. A synergistic mindsets intervention protects adolescents from stress. Nature 2022, 607, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crum, A.J.; Akinola, M.; Martin, A.; Fath, S. The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety Stress Coping 2017, 30, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyer, J.P.; Akinola, M.; Grunberg, R.; Crum, A.J. Thriving Under Pressure: The Effects of Stress-Related Wise Interventions on Affect, Sleep, and Exam Performance for College Students from Disadvantaged Backgrounds. Emotion 2022, 22, 1755–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, A.J.; Santoro, E.; Handley-Miner, I.; Smith, E.N.; Evans, K.; Moraveji, N.; Achor, S.; Salovey, P. Evaluation of the “Rethink Stress” Mindset Intervention: A Metacognitive Approach to Changing Mindsets. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2023, 152, 2603–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoll, M.; Goetz, M.; Adriasola, E.; Al-Atwi, A.A.; Arenas, A.; Atitsogbe, K.A.; Barrett, S.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Blanco, N.D.; Bogilovic, S.; et al. International differences in employee silence motives: Scale validation, prevalence, and relationships with culture characteristics across 33 countries. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 619–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Eatough, E.M.; Ford, M.T. Relationships between illegitimate tasks and change in work-family outcomes via interactional justice and negative emotions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 104, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six-factor model (IT, SM, CA, HA, TC, and CY) | 830.620 | 449 | 1.850 | 0.055 | 0.056 | 0.904 | 0.894 |

| Five-factor model (IT, SM, CA + HA, TC, and CY) | 858.477 | 454 | 1.891 | 0.056 | 0.058 | 0.898 | 0.889 |

| Five-factor model (IT, SM, CA, HA, and TC + CY) | 1076.830 | 454 | 2.372 | 0.069 | 0.074 | 0.843 | 0.829 |

| Five-factor model (IT + SM, CA, HA, CY, and TC) | 1626.906 | 454 | 3.583 | 0.095 | 0.107 | 0.705 | 0.678 |

| Four-factor model (IT + SM, CA + HA, TC, and CY) | 1650.336 | 458 | 3.603 | 0.096 | 0.107 | 0.700 | 0.675 |

| Three-factor model (IT + SM, CA + TC, and HA + CY) | 1887.003 | 461 | 4.093 | 0.104 | 0.120 | 0.641 | 0.614 |

| Two-factor model (IT + SM + CA + HA, and TC + CY) | 2022.411 | 463 | 4.368 | 0.109 | 0.116 | 0.608 | 0.580 |

| One-factor model (IT + SM + CA + HA + TC + CY) | 2249.619 | 464 | 4.848 | 0.116 | 0.114 | 0.551 | 0.520 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | ||||||||

| 2. Age | −0.026 | - | |||||||

| 3. Education | −0.054 | −0.163 ** | - | ||||||

| 4. Illegitimate tasks | 0.019 | −0.223 *** | −0.016 | - | |||||

| 5. Stress mindset | −0.109 | 0.151 * | 0.015 | −0.333 *** | - | ||||

| 6. Challenge appraisal | −0.092 | 0.098 | −0.046 | −0.274 *** | 0.582 *** | - | |||

| 7. Hindrance appraisal | 0.054 | −0.134 * | 0.087 | 0.337 *** | −0.495 *** | −0.698 *** | - | ||

| 8. Task crafting | −0.042 | 0.122 * | 0.094 | −0.313 *** | 0.509 *** | 0.525 *** | −0.398 *** | - | |

| 9. Cyberloafing | 0.050 | −0.268 *** | −0.025 | 0.483 *** | −0.292 *** | −0.316 *** | 0.361 *** | −0.375 *** | - |

| Mean | 1.59 | 31.00 | 3.03 | 2.45 | 3.84 | 4.31 | 1.70 | 3.68 | 2.17 |

| SD | 0.49 | 6.94 | 0.57 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.68 |

| Challenge Appraisal | Hindrance Appraisal | Task Crafting | Cyberloafing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE |

| Intercepts | 4.496 *** | 0.153 | 1.885 *** | 0.163 | 0.669 | 0.438 | 1.885 *** | 0.163 |

| Controls | ||||||||

| Gender | −0.039 | 0.043 | −0.026 | 0.059 | 0.009 | 0.062 | 0.083 | 0.067 |

| Age | 0.000 | 0.003 | −0.007 * | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.005 | −0.01 * | 0.005 |

| Education | −0.027 | 0.028 | 0.012 | 0.038 | 0.124 * | 0.056 | 0.002 | 0.053 |

| Independent variable | ||||||||

| Illegitimate tasks | −0.046 | 0.034 | 0.131 ** | 0.043 | −0.148 ** | 0.050 | 0.353 *** | 0.057 |

| Mediators | ||||||||

| Challenge appraisal | 0.577 *** | 0.075 | ||||||

| Hindrance appraisal | 0.266 ** | 0.085 | ||||||

| Moderator | ||||||||

| Stress mindset | 0.349 *** | 0.057 | −0.318 *** | 0.067 | ||||

| Interaction | ||||||||

| Illegitimate tasks * Stress mindset | 0.223 *** | 0.056 | −0.245 *** | 0.065 | ||||

| R2 | 0.149 *** | 0.028 | 0.246 *** | 0.042 | 0.265 *** | 0.021 | 0.323 *** | 0.040 |

| Path | Estimate | SE | Bootstrap 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illegitimate tasks → challenge appraisal | 0.223 *** | 0.056 | [0.088, 0.303] |

| High stress mindset (+1 SD) | 0.116 ** | 0.037 | [0.047, 0.191] |

| Low stress mindset (−1 SD) | −0.208 ** | 0.065 | [−0.313, −0.065] |

| Illegitimate tasks → hindrance appraisal | −0.245 *** | 0.065 | [−0.341, −0.096] |

| High stress mindset (+1 SD) | −0.047 | 0.056 | [−0.155, 0.062] |

| Low stress mindset (−1 SD) | 0.309 *** | 0.072 | [0.154, 0.423] |

| Paths | Estimate | SE | Bootstrap 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illegitimate tasks → challenge appraisal → task crafting | |||

| Low stress mindset (−1 SD) | −0.120 *** | 0.034 | [−0.176, −0.053] |

| Medium stress mindset | −0.027 | 0.019 | [−0.061, 0.011] |

| High stress mindset (+1 SD) | 0.067 ** | 0.022 | [0.030, 0.116] |

| Difference (high vs. low stress mindset) | 0.187 *** | 0.042 | [0.106, 0.250] |

| Illegitimate tasks → hindrance appraisal → cyberloafing | |||

| Low stress mindset (−1 SD) | 0.082 * | 0.033 | [0.029, 0.162] |

| Medium stress mindset | 0.035 * | 0.017 | [0.009, 0.083] |

| High stress mindset (+1 SD) | −0.012 | 0.015 | [−0.048, 0.013] |

| Difference (high vs. low stress mindset) | −0.095 * | 0.038 | [−0.183, −0.031] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Q.; Xie, Y. The Effects of Illegitimate Tasks on Task Crafting and Cyberloafing: The Role of Stress Mindset and Stress Appraisal. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070600

Ma Q, Xie Y. The Effects of Illegitimate Tasks on Task Crafting and Cyberloafing: The Role of Stress Mindset and Stress Appraisal. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):600. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070600

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Qian, and Yuxuan Xie. 2024. "The Effects of Illegitimate Tasks on Task Crafting and Cyberloafing: The Role of Stress Mindset and Stress Appraisal" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070600

APA StyleMa, Q., & Xie, Y. (2024). The Effects of Illegitimate Tasks on Task Crafting and Cyberloafing: The Role of Stress Mindset and Stress Appraisal. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070600