Family Support, Resilience, and Life Goals of Young People in Residential Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlation among Family Support, Resilience, and Goal Setting

3.2. Variance in Family Support, Resilience, and the Goal-Setting Process According to Sex and Family Participation in LP

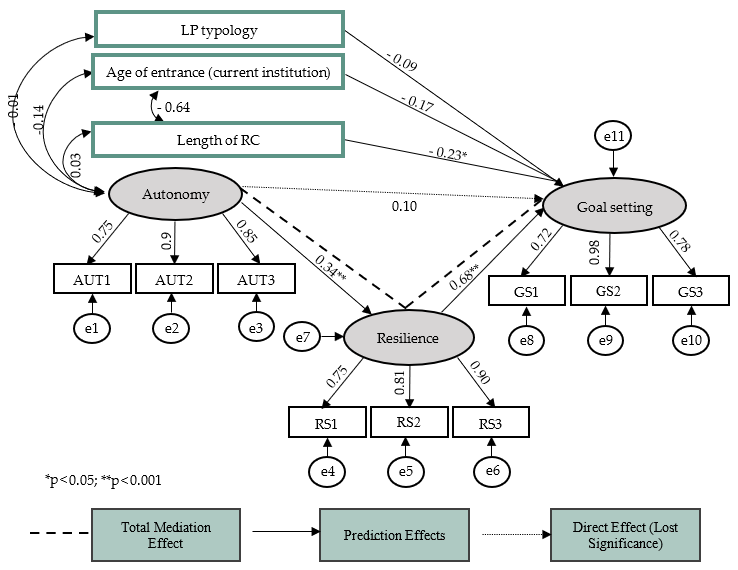

3.3. Mediating Effect of Resilience on the Relationship between Family Support (Autonomy) and Goal Setting

4. Discussion

Practical Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development, 2nd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss (Vol. 1: Attachment), 2nd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969; pp. 1–401. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment in Adulthood. Stricture, Dynamics, and Change, 1st ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maurović, I.; Liebenberg, L.; Ferić, M. A review of family resilience: Understanding the concept and operationalization challenges to inform research and practice. Child Care Pract. 2020, 26, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, C.P.; Matos, P.M. Adolescents in institutional care: Significant adults, resilience and well-being. Child Youth Care Forum 2015, 44, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzi, S.; Pace, C.S. Multiple facets of attachment in residential care, late adopted, and community adolescents: An interview-based comparative study. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2022, 24, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsells, M.À.; Pastor, C.; Mateos, A.; Vaquero, E.; Urrea, A. Exploring the needs of parents for achieving reunification: The views of foster children, birth family and social workers in Spain. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 48, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulimani-Aidan, Y. Future expectations as a source of resilience among young people leaving care. Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 1111–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecompte, V.; Pascuzzo, K.; Hélie, S. A look inside family reunification for children with attachment difficulties: An exploratory study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 154, 107140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovers, A.; Blankestein, A.; Van der Rijken, R.; Scholte, R.; Lange, A. Treatment outcomes of a shortened secure residential stay combined with multisystemic therapy: A pilot study. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2019, 63, 2654–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.S.; Calheiros, M.M.; Carvalho, H.; Magalhães, E. Organizational social context and psychopathology of youth in residential care: The intervening role of youth–caregiver relationship quality. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 71, 564–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells Bailón, M.A.; Mateos Inchaurrondo, A.; Urrea Monclús, A.; Vaquero Tió, E. Positive parenting support during family reunification. Early Child Dev. Care 2018, 188, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palareti, L.; Berti, C. Relational climate and effectiveness of residential care: Adolescent perspectives. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2010, 38, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto de Segurança Social, I.P. CASA 2021-Relatório de Caracterização Anual da Situação de Acolhimento das Crianças e Jovens. Instituto de Segurança Social, I.P. 2022. Available online: https://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/13200/Relatório+CASA_2021/d6eafa7c-5fc7-43fc-bf1d-4afb79ea8f30 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Mota, C.P.; Oliveira, I. O suporte social e a personalidade são significativos para os objetivos de vida de adolescentes de diferentes configurações familiares? Anal. Psicol. 2017, 35, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Snyder, C.R. Handbook of Hope: Theory, Measures, and Applications, 1st ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sulimani-Aidan, Y.; Schwartz-Tayri, T.; Melkman, E. Future expectations of adolescents: The role of mentoring, family engagement, and sense of belonging. Youth Soc. 2020, 53, 1001–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ahn, H.; Bright, C.L. Family involvement meetings: Engagement, facilitation, and child and family goals. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 79, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.; de Haan, A.D.; Kuiper, C.H.; Harder, A.T. Family-centred practice and family outcomes in residential youth care: A systematic review. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2024, 29, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, E.J.S.; Cavalcante, L.I.C.; Pedroso, J.S. Rede de apoio social e afetivo de adolescentes em acolhimento institucional e de seus familiares. Psicol. Argum. 2022, 40, 1751–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, S.; Wright, A.C.; McLean, L.; Buratti, S. Trauma-informed family contact practice for children in out-of-home care. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 1837–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, R.H. Depressed outpatients’s life contexts, amount of treatment and treatment outcome. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1990, 178, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, V.; Boyd, L.M. Factors associated with perceptions of family belonging among adolescents. J. Marriage Fam. 2016, 78, 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasli, F.; Aslantürk, H. Examining the family belonging of adults with institutional care experience in childhood. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berástegui, A.; Pitillas, C. What does it take for early relationships to remain secure in the face of adversity? Attachment as a unit of resilience. In Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change, 1st ed.; Ungar, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Fleury, M.J.; Xiang, Y.T.; Li, M.; D’arcy, C. Resilience and protective factors among people with a history of child maltreatment: A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson-Arad, B.; Navaro-Bitton, I. Resilience among adolescents in foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 59, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M.; Magalhães, E.; Baptista, J. Adolescents’ resilience in residential care: A systematic review of factors related to healthy adaptation. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 15, 819–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M.; Magalhães, E.; Calheiros, M.M.; Macdonald, D. Quality of relationships between residential staff and youth: A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekes, N.; Gingras, I.; Philippe, F.L.; Koestner, R.; Fang, J. Parental autonomy-aupport, intrinsic life goals, and well-being among adolescents in China and north America. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, E.K.; Gebhardt, W.A.; Garnefski, N. Adolescent goal content and pursuit: A review of the literature from the past 16 years. Rev. Dev. 2008, 28, 421–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sandoval, Y.; Aragón, C.; Verdugo, L. Future expectations of adolescents in Residential Care: The role of self-perceptions. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 143, 106686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenne, R.L.; Man, T. Self-Regulation. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology. The Social Bases of Health Behavior, 1st ed.; Coen, L.M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 4, pp. 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulimani-Aidan, Y. To dream the impossible dream: Care leavers’ challenges and barriers in pursuing their future expectations and goals. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 81, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, P.; Ortiz-Bermúdez, A.U.; Rodríguez-Mora, A.; Verdugo, L.; Śanchez-Sandoval, Y. Future expectations of adolescents from different social contexts. An. Psicol. 2023, 39, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, N.; Nelson, L. Moving toward and away from others: Social orientations in emerging adulthood. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 58, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.I.; Cheng, C.L. Purpose profiles among Chinese adolescents: Association with personal characteristics, parental support, and psychological adjustment. J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 17, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liga, F.; Lo Coco, A.; Musso, P.; Inguglia, C.; Costa, S.; Lo Cricchio, M.G.; Ingoglia, S. Parental psychological control, autonomy support and Italian emerging adult’s psychosocial well-being: A cluster analytic approach. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 17, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maree, J.G.; Twigge, A. Career and self-construction of emerging adults: The value of life designing. Front. Psychol. 2016, 6, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellers, D.E.; Smith, E.G.; Izzo, C.V.; McCabe, L.A.; Nunno, M.A. Child feelings of safety in residential care: The supporting role of adult-child relationships. Resid. Treat. Child. Youth 2020, 37, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development; Lerner, R.M., Damon, W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 795–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Gómez-Mármol, A.; Conte Marín, L.; Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Future academic expectations and their relationship with motivation, satisfaction of psychological needs, responsibility, and school social climate: Gender and educational stage. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, C.P.; Gonçalves, T.; Carvalho, H.; Costa, M. The role of attachment in the life aspirations of Portuguese adolescents in residential care: The mediating effect of emotion regulation. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2022, 41, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeira, A.; Dekel, R. Adolescents’ self-image and its relationship with their perceptions of the future. Int. Soc. Work 2005, 48, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Teng, F.; Yang, W. Awareness of societal emphasis on appearance decreases women’s (but not men’s) career aspiration: A serial mediation model. Scand. J. Psychol. 2021, 62, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.; Matos, P.M.; Santos, B.; Carvalho, H.; Ferreira, T.; Mota, C.P. We stick together! COVID-19 and psychological adjustment in youth residential care. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 130, 105370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, E.; Serna, C.; Martínez, I.; Cruise, E. Parental attachment and peer relationships in adolescence: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrício, J.N.; Lopes, D.; Garrido, M.V.; Calheiros, M.M. The social image of families of children and youth in residential care: A characterization and comparison with mainstream families with different socioeconomic status. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 2146–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, C.; Santos, A.C.; Canha, L.; Matos, M.G.D. Resiliência na adolescência: Género e a idade fazem a diferença? J. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 10, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mota, C.P.; Gonçalves, T.; Carvalho, H.; Costa, M. Attachment, emotional regulation and perception of the institutional environment in adolescents in residential care context. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2023, 40, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babo, M.F.; Carvalho, H.; Santos, B.; Matos, P.M.; Mota, C.P. Affective relationships with caregivers, self-efficacy, and hope of adolescents in residential care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2024, 157, 107438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babo, F.; Mota, C.P.; Santos, B.; Matos, M.P.; Carvalho, H. I just know I am upset, and thats it!: The role of adolescents attachment, emotions, and relationship with caregivers in residential care. Child Abuse Rev. 2023, 33, e2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockting, W.O.; Miner, M.H.; Romine, R.E.S.; Hamilton, A.; Coleman, E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etherton, K.; Steele-Johnson, D.; Salvano, K.; Kovacs, N. Effects of resilience on student performance and well-being: The role of self-efficacy, self-set goals, and anxiety. J. Gen. Psychol. 2022, 149, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Soto, E.; Pereda, N.; Guilera, G. Poly-victimization, resilience, and suicidality among adolescents in child and youth-serving systems. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 106, 104500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I.; Augusto-Landa, J.M.; Quijano-López, R.; León, S.P. Self-concept as a mediator of the relationship between resilience and academic performance of university students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 747168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.X.; Yang, H.M.; Tong, K.K.; Wu, A.M. The prospective effect of life purpose on gambling disorder and psychological flourishing among college students. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, M.N. Development of Inventário de Percepção de Suporte Familiar (IPSF): Preliminary psychometrics studies. Psico USF 2005, 10, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, K.B.; Neal, D.J.; Collins, S.E. A psychometric analysis of the self-regulation questionnaire. Addict. Behav. 2004, 29, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Del Castillo, J.A.; Dias, P.C. Auto-regulação, resiliência e consumo de substâncias na adolescência: Contributos da adaptação do questionário reduzido de auto-regulação. Psicol. Saúd. Doenças 2009, 10, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nunes, F.; Mota, C.P.; Schoon, I.; Ferreira, T.; Matos, P.M. Sense of personal agency in adolescence and young adulthood: A preliminary assessment model. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2022, 196, 111754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, G.M.; Young, H.M. Development and psychometric evaluation of resilience scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1993, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, A.M.P.M.P.C.; Camarneiro, A.P. Validação da Resilience Scale de Wagnild e Young em contexto de acolhimento residencial de adolescentes. Rer. Enferm. Ref. 2018, 4, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 156–180. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Pawer Analisys for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 109–139. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, A.; Oliva, A.; Reina, M.C. Family relationships from adolescence to emerging adulthood: A longitudinal study. J. Fam. Issues 2015, 36, 2002–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerig, P.K. For better or worse: Intimate relationships as sources of risk or resilience for girls’ delinquency. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Låftman, S.B.; Modin, B. School-performance indicators and subjective health complaints: Are there gender differences? Sociol. Health Illn. 2012, 34, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peisch, V.; Dale, C.; Parent, J.; Burt, K. Parent socialization of coping and child emotion regulation abilities: A longitudinal examination. Fam. Proc. 2020, 59, 1722–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Blanc, N.; Senar-Morera, F.; Ros-Morente, A.; Filella-Guiu, G. Does emotional awareness lead to resilience? Sex-based differences in adolescence. Rev. Psicodidact. 2023, 28, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Martos, M.; Fernández-Sánchez, M.D.; Lopez-Zafra, E. Measurement invariance across sex and age in the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in a general Spanish population. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limura, S.; Taku, K. Gender differences in relationship between resilience and big five personality traits in Japanese adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 2018, 121, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurault, J.C.; Broc, G.; Crône, L.; Tedesco, A.; Brunel, L. Measuring the sense of agency: A French adaptation and validation of the sense of agency scale (F-SoAS). Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 584145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korlat, S.; Foerst, N.M.; Schultes, M.T.; Schober, B.; Spiel, C.; Kollmayer, M. Gender role identity and gender intensification: Agency and communion in adolescents’ spontaneous self-descriptions. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 19, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, K.; Venables, J.; Walsh, T. Supporting birth parents’ relationships with children following removal: A scoping review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 149, 106961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, A.B.; Del Valle, J.F. Las redes de apoyo social de los adolescentes acogidos en residencias de protección. Un análisis comparativo con población normativa. Psicothema 2003, 15, 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, J.E.; Mendonça, M.; Coimbra, S.; Fontaine, A.M. Family support in the transition to adulthood in Portugal–Its effects on identity capital development, uncertainty management and psychological well-being. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 1449–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Collins, W.A. Autonomy development during adolescence. In Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence, 1st ed.; Adams, G.R., Berzonsky, M., Eds.; Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I.; Cook, R. Can individual agency compensate for background disadvantage? Predicting tertiary educational attainment among males and females. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijbroek, B.; Strating, M.M.; Huijsman, R. Integrating family strengths in child protection goals. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Hu, N.; Yu, H.; Xiao, H.; Luo, J. Parenting style and adolescent mental health: The chain mediating effects of self-esteem and psychological inflexibility. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 738170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrens, K.R.; DuBois, D.L.; Garrison, M.; Spencer, R.; Richardson, L.P.; Lozano, P. Qualitative exploration of relationships with important non-parental adults in the lives of youth in foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurita, J.F. Recursos residenciales para menores. In Manual de Protección Infantil, 2nd ed.; Ochotorena, J.P., Madariaga, M.I.A., Eds.; Elsevier Masson: Madrid, Spain, 2000; pp. 393–445. [Google Scholar]

- Seginer, R. Future orientation in times of threat and challenge: How resilient adolescents construct their future. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2008, 32, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, J.R.; Batista, C.V.; Ribeiro, E.J.; Cordeiro, L. Projeto de vida em lares de infância e juventude: Perspectivas dos técnicos. J. Child Adol. Psychol. 2016, 7, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelaar, M.D.; Harder, A.T.; Kalverboer, M.E.; Post, W.J.; Knorth, E.J. Participation of youth in decision-making procedures during residential care: A narrative review. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2018, 23, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar-Schwartz, S. Parental availability of support and frequency of contact: The reports of youth in educational residential care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 101, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat, C. The child protection system from the perspective of young people: Messages from 3 studies. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family support | ||||

| 1. Autonomy | - | |||

| 2. Adaptation | 0.471 ** | - | ||

| 3. Resilience | 0.269 ** | 0.253 ** | - | |

| 4. Goal setting | 0.307 ** | 0.274 ** | 0.631 ** | - |

| M | 2.97 | 3.18 | 5.35 | 4.00 |

| SD | 0.830 | 0.789 | 0.987 | 0.780 |

| Variable | Sex | IC95% | Direction of Significant Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Male (n = 75) M ± SD | 2. Female (n = 49) M ± SD | |||

| Family support | ||||

| Autonomy | 3.03 ± 0.832 | 2.88 ± 0.826 | [−0.156; 0.447] | n.s. |

| Adaptation | 3.32 ± 0.796 | 2.97 ± 0.739 | [0.006; 0.629] | 1 > 2 |

| Resilience | 5.54 ± 0.897 | 5.06 ± 1.056 | [0.130; 0.830] | 1 > 2 |

| Goal setting | 4.15 ± 0.785 | 3.77 ± 0.718 | [0.111; 0.664] | 1 > 2 |

| Variables | Family Participation in the LP | IC95% | Direction of Significant Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Yes (n = 60) M ± SD | 2. No (n = 35) M ± SD | |||

| Family support | ||||

| Autonomy | 3.15 ± 0.802 | 2.91 ± 0.864 | [−0.108; 0.589] | n.s. |

| Adaptation | 3.46 ± 0.631 | 2.73 ± 0.891 | [0.380; 1.067] | 1 > 2 |

| Resilience | 5.65 ±0.933 | 5.17 ± 0.921 | [0.091; 0.875] | 1 > 2 |

| Goal setting | 4.17 ± 0.764 | 3.81 ± 0.825 | [0.035; 0.700] | 1 > 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alves, C.P.; Relva, I.C.; Costa, M.; Mota, C.P. Family Support, Resilience, and Life Goals of Young People in Residential Care. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070581

Alves CP, Relva IC, Costa M, Mota CP. Family Support, Resilience, and Life Goals of Young People in Residential Care. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):581. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070581

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlves, Cristina Peixoto, Inês Carvalho Relva, Mónica Costa, and Catarina Pinheiro Mota. 2024. "Family Support, Resilience, and Life Goals of Young People in Residential Care" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070581

APA StyleAlves, C. P., Relva, I. C., Costa, M., & Mota, C. P. (2024). Family Support, Resilience, and Life Goals of Young People in Residential Care. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070581