Harnessing Workplace Ostracism: Unleashing Proactive Behavior through Work Focus and Visionary Leadership

Abstract

I can’t change the direction of the wind, but I can adjust my sails to always reach my destination.—Jimmy Dean

1. Introduction

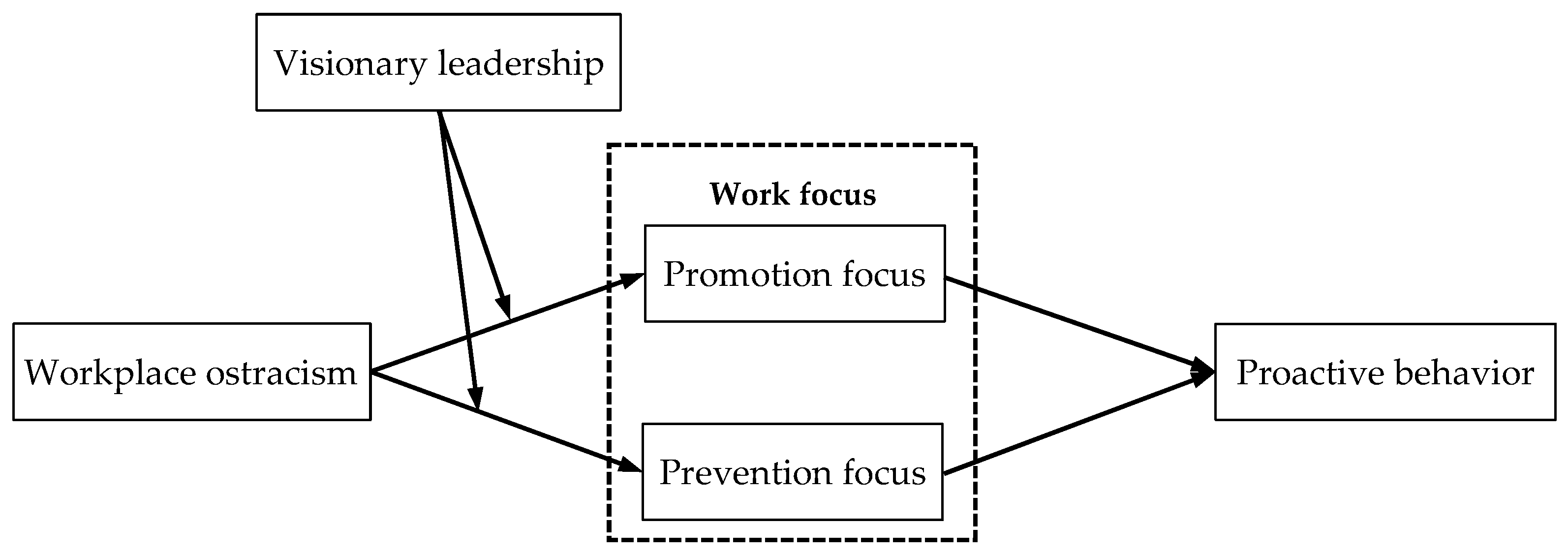

2. Theoretical Overview and Hypotheses

2.1. Regulatory Focus Theory

2.2. Workplace Ostracism and Work Focus

2.3. The Mediating Role of Work Focus between Workplace Ostracism and Proactive Behavior

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Visionary Leadership

2.5. The Moderated Mediation Model

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analyses

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.5. Common Method Bias

3.6. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficient

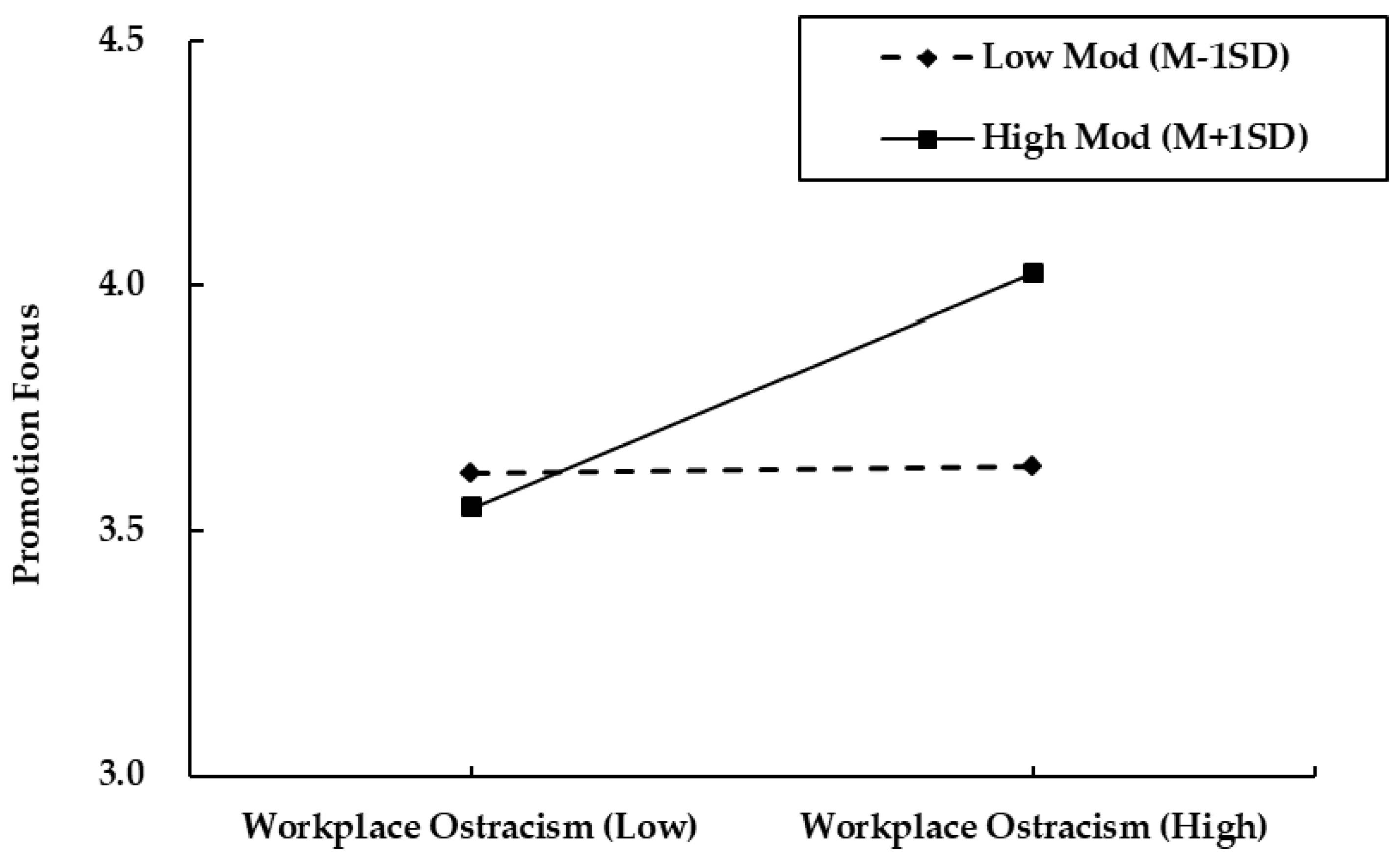

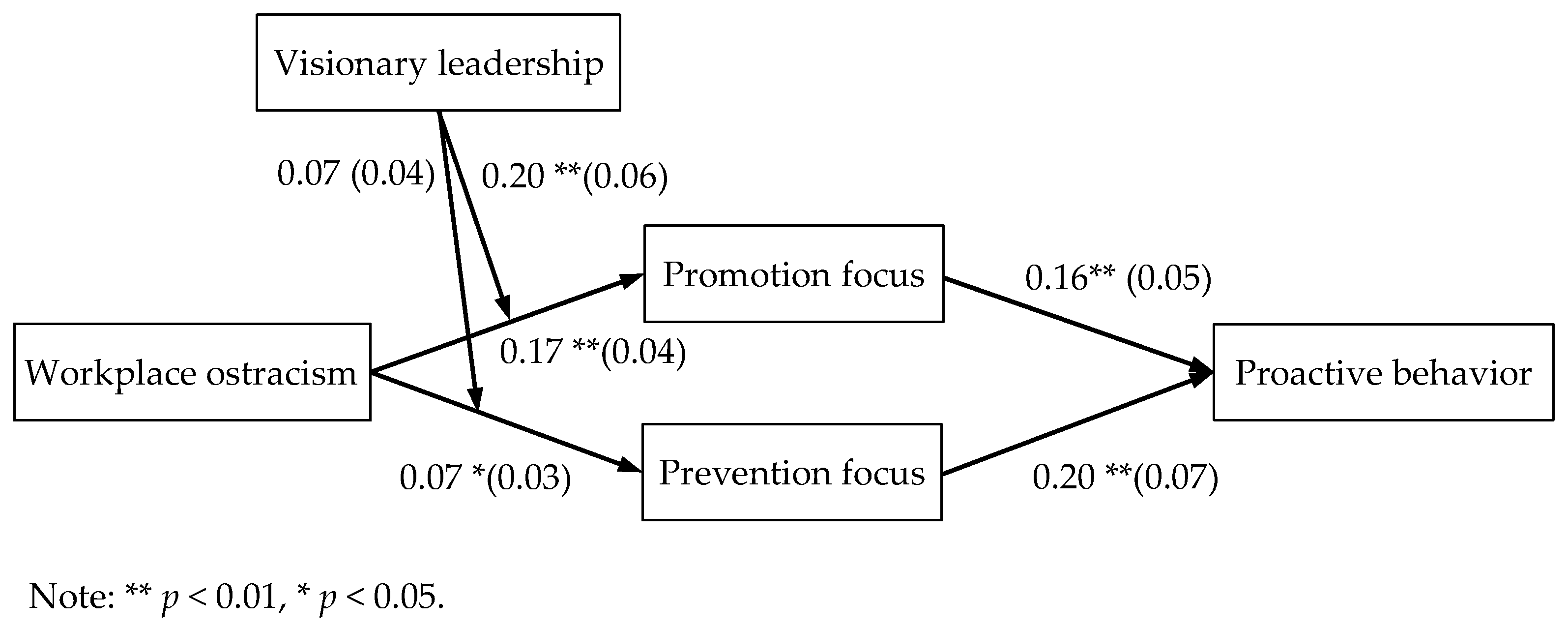

3.7. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, N.; Dhar, R.L. Workplace ostracism: A process model for coping and typologies for handling ostracism. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2024, 34, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.J.; Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Vogel, R.M. The cost of being ignored: Emotional exhaustion in the work and family domains. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, H.K.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Lee, C. Workplace ostracism and employee creativity: An integrative approach incorporating pragmatic and engagement roles. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Yuan, C. Workplace ostracism and helping behavior: A cross-level investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 190, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Liu, J.; Hui, C.; WU, R.R. The Effect of Workplace Ostracism on Proactive Behavior: The Self-Verification Theory Perspective. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2015, 47, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.K.; Iqbal, J.; Fatima, T.; Iqbal, S.M.J.; Jamal, W.N.; Nawaz, M.S. Why do I contribute to organizational learning when I am ostracized? A moderated mediation analysis. J. Manag. Organ. 2022, 28, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Liu, B.; Li, F.Y.; Wei, X. The Double-Edged Sword Effect of Workplace Ostracism on Employee Innovative Performance. Chin. J. Manag. 2020, 17, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.K.; Collins, C.G. Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Huang, X.; Robinson, S.L. When self-view is at stake: Responses to ostracism through the lens of self-verification theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 2281–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.Y.; Wu, Q.Q.; Hu, W.F. Impacts of Paradoxical Leadership Behavior on Employee Creativity. Manag. Rev. 2022, 34, 215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.T.; Zhang, Z.T.; Zhao, L.J. Does Time Pressure Promotes or Prohibits employees’ Innovation Behavior? A Moderated Double Path Model. Sci. Sci. Manag. Sci. Tech. 2020, 41, 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cruz, T.F.; Botella-Carrubi, D.; Martínez-Fuentes, C.M. Supervisor leadership style, employee regulatory focus, and leadership performance: A perspectivism approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipfelsberger, P.; Raes, A.; Herhausen, D.; Kark, R.; Bruch, H. Start with why: The transfer of work meaningfulness from leaders to followers and the role of dyadic tenure. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 1287–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, D.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Wisse, B. Focusing on followers: The role of regulatory focus and possible selves in visionary leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Waldman, D.A.; Balthazard, P.A.; Ames, J.B. Leader self-projection and collective role performance: A consideration of visionary leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2023, 34, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Fan, X.; Wang, Q. Linking visionary leadership to creativity at multiple levels: The role of goal-related processes. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 167, 114182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lee, C.; Hui, C.; Lin, W.; Brown, G.; Liu, J. Feeling possessive, performing well? Effects of job-based psychological ownership on territoriality, information exchange, and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 108, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, E.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1997, 69, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Van Dijk, D. Keep your head in the clouds and your feet on the ground: A multi-focal review of leadership-followership self-regulatory focus. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 509–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Higgins, E.T.; Low, M.B. Regulatory focus theory and the entrepreneurial process. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaj, K.; Chang, C.H.; Johnson, R.E. Regulatory focus and work-related outcomes: A review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 998–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamache, D.L.; Neville, F.; Bundy, J.; Short, C.E. Serving differently: CEO regulatory focus and firm stakeholder strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 1305–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.E.; Chang, C.H.; Yang, L.Q. Commitment and motivation at work: The relevance of employee identity and regulatory focus. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 226–245. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, D.L.; Brown, D.J.; Berry, J.W.; Lian, H. The development and validation of the Workplace Ostracism Scale. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1348–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ng, T.W.H.; Lam, S.S.K. Promotion- and prevention-focused coping: A meta-analytic examination of regulatory strategies in the work stress process. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 1296–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.; Mathmann, F.; Jin, H.S.; Higgins, E.T. How regulatory focus–mode fit impacts variety-seeking. J. Consum. Psychol. 2023, 33, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Long, L.R.; Zhang, Y. The Relationship between Newcomers’ I-deals and Coworkers’ Ostracism and Self-improvement: The Mediating Role of Envy and the Moderating Role of Organizational Overall Justice. Manag. Rev. 2021, 33, 234–244. [Google Scholar]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Phetvaroon, K.; Li, J. Left out of the office “tribe”: The influence of workplace ostracism on employee work engagement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2717–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.; Cogswell, J.; Smith, M.B. The antecedents and outcomes of workplace ostracism: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Williams, H.M.; Turner, N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A.; Talwar, S.; Masood, A.; Dhir, A. Does enterprise social media use promote employee creativity and well-being? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekman, D.R.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Pratt, M.G. Channeling identification: How perceived regulatory focus moderates the influence of organizational and professional identification on professional employees’ diagnosis and treatment behaviors. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 753–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, M.C.; Hoefsmit, N.; Van Ruysseveldt, J.; van Dam, K. Exploring proactive behaviors of employees in the prevention of burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3849–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, T.J. Structure Exploration and Scale Development on Employee’s Proactive Behavior. J. Technol. Econ. 2018, 37, 57–62+128. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, P.W.; Fischbach, A. A meta-analysis on promotion- and prevention-focused job crafting. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yang, F.; Li, Y.Q. Workplace ostracism: A review on mechanisms and localization development. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 25, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Wang, Y.; Liao, J. When is proactivity wise? A review of factors that influence the individual outcomes of proactive behavior. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idson, L.C.; Liberman, N.; Higgins, E.T. Distinguishing gains from nonlosses and losses from nongains: A regulatory focus perspective on hedonic intensity. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 36, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascareño, J.; Rietzschel, E.; Wisse, B. Envisioning innovation: Does visionary leadership engender team innovative performance through goal alignment? Creat. Innov. Manag. 2020, 29, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.W.; Zhang, P.C.; Zhu, Y.H.; Li, Y. How and When Does Visionary Leadership Promote Followers? Taking Charge? The Roles of Inclusion of Leader in Self and Future Orientation. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 1917–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouzes, J.M.; Posner, B.Z. Great Leadership Creates Great Workplaces; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, E.; Shemla, M.; van Knippenberg, D.; Scholz, F.A. A paradox perspective on the interactive effects of visionary and empowering leadership. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2019, 155, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M.J.; Kacmar, K.M.; Carlson, D.S.; Chonko, L.B.; Roberts, J.A. Regulatory focus as a mediator of the influence of initiating structure and servant leadership on employee behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.P.; Shi, K. The Structure and Measurement of Transformational Leadership in China. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2005, 37, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Huang, B.B.; Tang, D.D. Preliminary work for modeling questionnaire data. J. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 41, 204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.L.; Ye, B. Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, J.Y.; Yuan, M.; Chen, C.C. More pain, more change? The mediating role of presenteeism and the moderating role of ostracism. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 44, 902–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, X.; Muskat, B.; Leung, X.Y.; Liu, S. Employees’ self-esteem in psychological contract: Workplace ostracism and counterproductive behavior. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Yuan, L.; Wang, J.; Wan, Q. When the victims fight back: The influence of workplace ostracism on employee knowledge sabotage behavior. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 1249–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imada, H.; Hopthrow, T.; Abrams, D. The role of positive and negative gossip in promoting prosocial behavior. Evol. Behav. Sci. 2021, 15, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, X.; Shan, L.; Xue, Z.; Haiyan, Y. Does negative evaluation make you lose yourself? Effects of negative workplace gossip on workplace prosocial behavior of employee. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 13541–13554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khush, G.S.; McCouch, S.R.; Ronald, P.C. Remembering MS Swaminathan: An outstanding scientist and visionary leader. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2320944121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | Combination | χ2 | df | GFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model | WO, Pro, Pre, PB, VL | 1352.312 | 815 | 0.840 | 0.905 | 0.914 | 0.045 |

| Four-factor model | WO, VL, Pro+Pre, PB | 2108.120 | 854 | 0.745 | 0.788 | 0.799 | 0.067 |

| Three-factor model | WO+VL, Pro+Pre, PB | 2868.270 | 857 | 0.648 | 0.660 | 0.678 | 0.085 |

| Two-factor model | WO+VL, WF+PB | 3104.639 | 859 | 0.630 | 0.622 | 0.640 | 0.090 |

| One-factor model | WO+VL+WF+PB | 4741.053 | 860 | 0.452 | 0.347 | 0.378 | 0.118 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.500 | 0.501 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 1.490 | 0.570 | −0.203 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Education level | 3.200 | 0.614 | 0.052 | −0.177 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Work time | 1.840 | 0.919 | −0.133 * | 0.575 ** | −0.124 * | 1 | |||||

| 5. Workplace ostracism | 3.039 | 0.928 | −0.068 | 0.057 | −0.119 * | 0.011 | 1 | ||||

| 6. Prevention focus | 4.092 | 0.482 | 0.037 | −0.099 | −0.016 | −0.043 | 0.135 * | 1 | |||

| 7. Promotion focus | 3.708 | 0.726 | −0.047 | −0.039 | 0.028 | −0.052 | 0.216 ** | 0.269 ** | 1 | ||

| 8. Proactive behavior | 4.040 | 0.571 | −0.022 | −0.065 | 0.008 | −0.073 | −0.007 | 0.214 ** | 0.235 ** | 1 | |

| 9. Visionary leadership | 3.989 | 0.632 | −0.036 | −0.054 | 0.053 | −0.008 | 0.031 | 0.216 ** | 0.150 ** | 0.511 ** | 1 |

| Effect | Path | β | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | Workplace ostracism → Prevention focus | 0.070 | 0.030 | [0.012, 0.127] |

| Workplace ostracism → Promotion focus | 0.169 | 0.043 | [0.088, 0.251] | |

| Prevention focus → Proactive behavior | 0.200 | 0.067 | [0.066, 0.329] | |

| Promotion focus → Proactive behavior | 0.162 | 0.050 | [0.068, 0.267] | |

| Workplace ostracism → Proactive behavior | −0.046 | 0.038 | [−0.123, 0.030] | |

| Mediating effect | Workplace ostracism → Prevention focus → Proactive behavior | 0.014 | 0.008 | [0.002, 0.014] |

| Workplace ostracism → Promotion focus → Proactive behavior | 0.027 | 0.011 | [0.010, 0.027] |

| Effect Relationship | Workplace Ostracism × Visionary Leadership → Promotion Focus | |

|---|---|---|

| Moderating Effect | 95% CI | |

| High level of visionary leadership | 0.257 ** | [0.158, 0.357] |

| Low level of visionary leadership | 0.008 | [−0.122, 0.138] |

| Effect Type | β | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace ostracism × Visionary leadership → Promotion focus → Proactive behavior | Visionary leadership (+1SD) | 0.049 | 0.015 | [0.022, 0.082] |

| Visionary leadership (mean) | 0.025 | 0.010 | [0.007, 0.048] | |

| Visionary leadership (−1SD) | 0.002 | 0.011 | [−0.023, 0.023] | |

| High–low (difference) | 0.048 | 0.017 | [0.018, 0.086] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, G.; Liu, S.; Zhong, J.; Yang, H. Harnessing Workplace Ostracism: Unleashing Proactive Behavior through Work Focus and Visionary Leadership. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070566

Xu G, Liu S, Zhong J, Yang H. Harnessing Workplace Ostracism: Unleashing Proactive Behavior through Work Focus and Visionary Leadership. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):566. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070566

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Guang, Shan Liu, Jie Zhong, and Haiyan Yang. 2024. "Harnessing Workplace Ostracism: Unleashing Proactive Behavior through Work Focus and Visionary Leadership" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070566

APA StyleXu, G., Liu, S., Zhong, J., & Yang, H. (2024). Harnessing Workplace Ostracism: Unleashing Proactive Behavior through Work Focus and Visionary Leadership. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070566