Family Climate as a Mediator of the Relationship between Stress and Life Satisfaction: A Study with Young University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

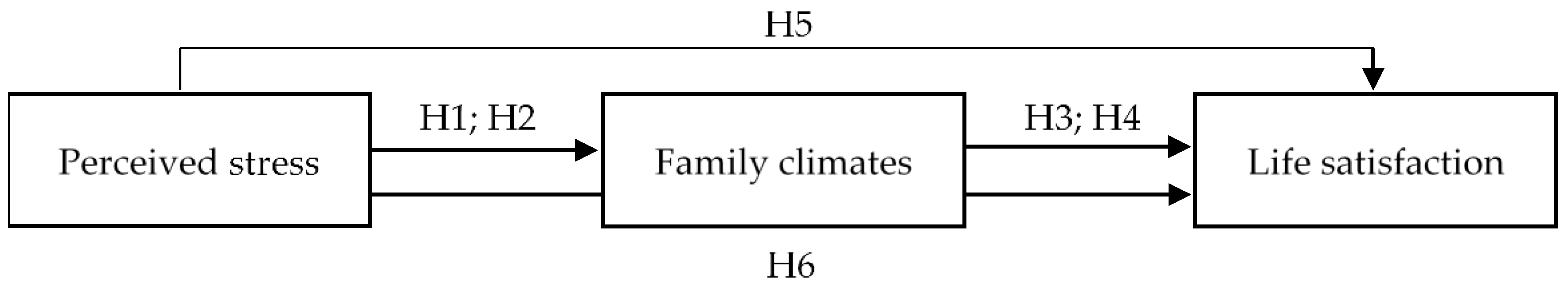

The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perceived Stress

2.2.2. Life Satisfaction

2.2.3. Family Climate

2.2.4. Socioeducational Information

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Correlational Analyses

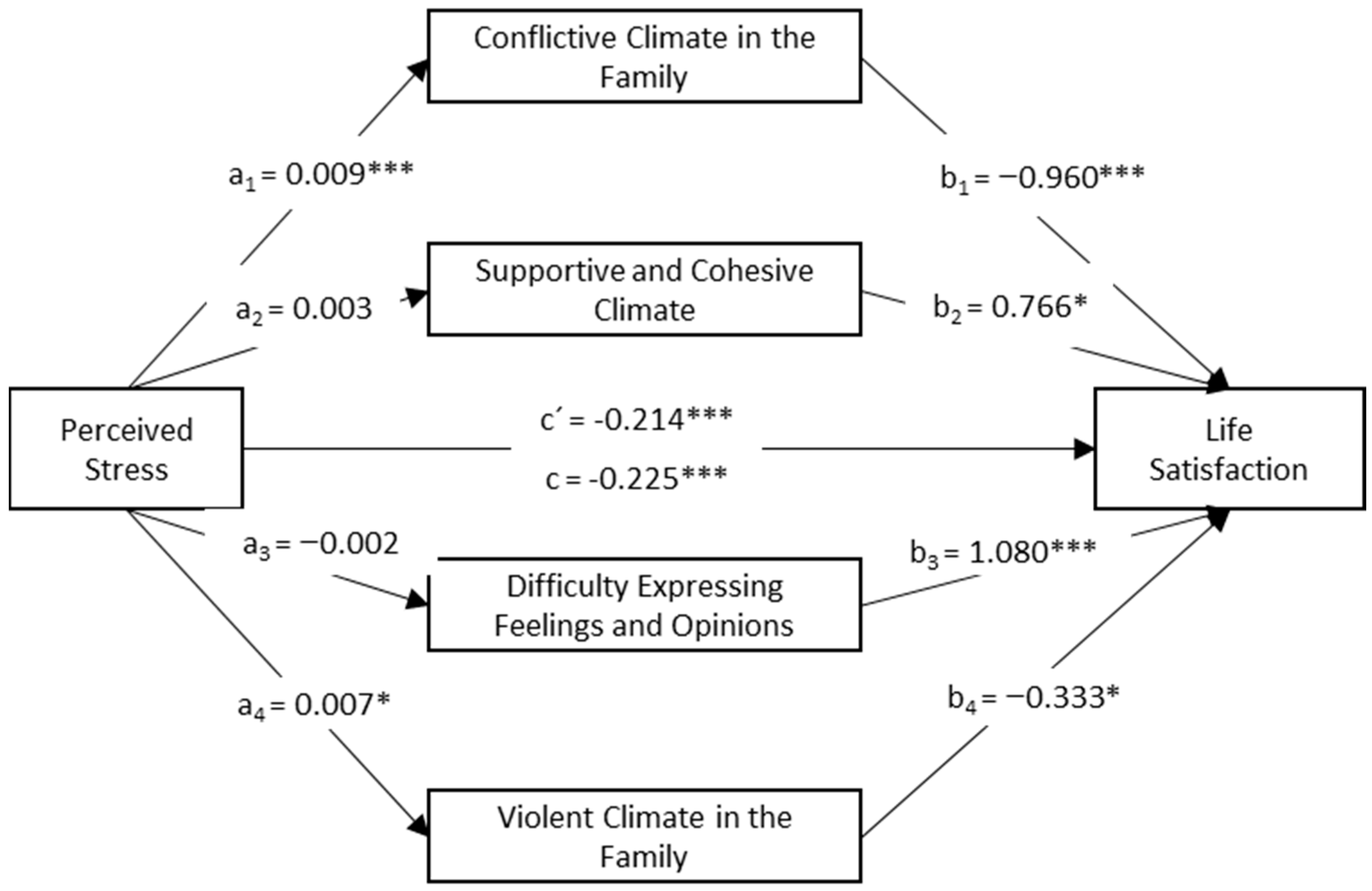

3.2. Parallel Mediation Model

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thorley, C. Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities; Institute for Public Policy Research: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/not-by-degrees (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Barkham, M.; Broglia, E.; Dufour, G.; Fudge, M.; Knowles, L.; Percy, A.; Turner, A.; Williams, C. Towards an evidence-base for student wellbeing and mental health: Definitions, developmental transitions and data sets. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2019, 19, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.; Spanner, L. The university mental health charter. Stud. Minds 2019. Available online: https://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/191208_umhc_artwork.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Selye, H. Stress without distress. Brux. Med. 1976, 56, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Welter, G.; Brandelli Costa, A.; Poletto, M.; Cassepp-Borget, V.; Dellaglio, D.D.; Helena Koller, S. Stressful life events, life satisfaction and positive and negative affect in youth at risk. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 102, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Inglehart, R.; Tay, L. Theory and Validity of Life Satisfaction Scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 112, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortegón, T.M.; Vinaccia, S.; Quiceno, J.M.; Capira, A.; Cerra, D.; Bernal, S. Apoyo social, resiliencia, estrés percibido, estrés postraumático, ansiedad, depresión y calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en líderes comunitarios víctimas del conflicto armado en los Montes de María, Sucre, Colombia. Eleuthera 2022, 24, 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, X.; Lara, G.E.; Sánchez, F.I. Cansancio emocional relacionado con el Estrés percibido durante el aprendizaje en modalidad E-learning en estudiantes de bachillerato. Boletín Científico Investigium Esc. Super. Tizayuca 2022, 7, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jiménez, D.; Rodríguez Medina, S.M.; Vélez Montalvo, V.; Maldonado Martínez, J.A.; Cabán Ruiz, M.A. Relación entre el estrés, la violencia de pareja y la satisfacción diádica en una muestra de personas adultas jóvenes en Puerto Rico. Salud Soc. 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M.E.; Vélez, M.L. Cansancio emocional. In Diccionario de Psicología y Educación; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., Ed.; Trillas: Ciudad de México, México, 2015; pp. 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- Usán, P.; Salavera, C.; Quílez, A.; Lozano, R.; Latorre, C. Empathy, self-esteem and satisfaction with life in adolescent. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 144, 106755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. The impact of family environment on the life satisfaction among young adults with personality as a mediator. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponti, L.; Smoti, M. The roles of parental attachment and sibling relationships on life satisfaction in emerging adults. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2018, 36, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, I.; Chaves, C.; Vázquez, C. Life Satisfaction. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Personality Processes and Individual Differences; Carducci, B.J., Nave, C.S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Bakkeli, N.Z. Health, work, and contributing factors on life satisfaction: A study in Norway before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melguizo Garín, A.; Martos-Méndez, M.J.; Hombrados-Mendieta, I.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, I. La resiliencia de los padres de niños con cáncer y su importancia en el manejo del estrés y la satisfacción vital. Psicooncología 2021, 18, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraza, A. La red de apoyo familiar y las relaciones intrafamiliares como predictoras de la satisfacción vital. Actual. Psicol. 2021, 35, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mendoza, M.C.; Parra, A.; Sánchez-Queija, I.; Oliveira, J.E.; Coimbra, S. Gender Differences in Perceived Family Involvement and Perceived Family Control during Emerging Adulthood: A Cross-Country Comparison in Southern Europe. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavarría, M.P.; Barra, E. Satisfacción Vital en Adolescentes: Relación con la Autoeficacia y el Apoyo Social Percibido. Ter. Psicológica 2014, 32, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yang, X.; Fan, C. Perceived stress and life satisfaction: A multiple mediation model of self-control and rumination. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 3091–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.B. Exploring the relationship between Perceived Stress and Life Satisfaction among college students: The Indian context. Indian J. Ment. Health 2017, 4, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanin, M.; Hassan, M.; Mohamed, F.; Abdel, D. Relationship between Ego Resilience, Perceived Stress and Life Satisfaction among University Students. J. Nurs. Sci. Benha Univ. 2022, 3, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydlik, M. Sharing Lives: Adult Children and Parents; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, R.; Conger, K.J. Resilience in midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Hong, P. COVID-19 and Mental Health of young adult children in China: Economic impact, family dynamics and resilience. Fam. Relat. 2021, 70, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, J.; Barreto, F. Clima familiar y su relación con el rendimiento académico en estudiantes de bachillerato. Rev. Psicol. Educ. 2020, 15, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, C.; Almeida, E. Clima social familiar t su influencia en la conducta violenta en los escolares. Rev. Científica Unemi 2017, 10, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, B. Family Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sucari, L.; Ticona, H.; Terán, A.; Chambi, N. Family climate and academic performance in university students during virtual education in times of COVID-19. Horizontes. Rev. Investig. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 5, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baya, D.; Pons-Salvador, G.; Gutiérrez, M.; Casas, F. Family, School, and Personal Factors as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being in Adolescents: A Cross-National Study in Eight European Countries. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 571999. [Google Scholar]

- Dymecka, J.; Gerymski, R.; Machnik-Czerwik, A. Fear of COVID-19 as a buffer in the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction in the Polish population at the beginning of the global pandemic. Health Psychol. Rep. 2021, 9, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulo, J.G.; Sánchez, M.G. Sources of stress among college students. CVCITC Res. J. 2014, 1, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Beiter, R.; Nash, R.; McCrady, M.; Rhoades, D.; Linscomb, M.; Clarahan, M.; Sammut, S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 6th ed.; Lerner, R.M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Tudge, J.R.H.; Mokrova, I.; Hatfield, B.E.; Karnik, R.B. Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human development. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2009, 1, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Qiu, X.; Qiao, Z.; Zhou, J.; Pan, H.; Ban, B.; Zhu, X.; et al. The Role of Family Environment in Depressive Symptoms among University Students: A Large Sample Survey in China. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Góngora, J.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, J.C.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, J.A. La inteligencia emocional como variable mediadora en la formación de estructuras familiares equilibradas. Know Share Psychol. 2020, 1, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.F.; Kelley, K.; Maxwell, S.E. Sample-size planning for more accurate statistical power: A method adjusting sample effect sizes for publication bias and uncertainty. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A. MedPower: An Interactive Tool for the Estimation of Power in Tests of Mediation [Computer Software]. 2017. Available online: https://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Remor, E. Psychometric properties of a European Spanish version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Span. J. Psychol. 2006, 9, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atienza, F.L.; Pons, D.; Balaguer, I.; García-Merita, M. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida en adolescentes. Psicothema 2000, 12, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, R.; Moos, B.; Trickett, E. FES, WES, CIES, CES. Escalas de Clima Social; TEA: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Marchena, R.; Martín, J.; Santana, R.; Alemán, J. Resumen Ejecutivo: Riesgo de Abandono Escolar Temprano y Continuidad Escolar en Canarias; Gobierno de Canarias, Consejería de Educación, Universidades y Sostenibilidad: Canarias, España, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associate: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, M.Q.; Qiu, H.Z. Mediation analysis and effect size measurement: Retrospect and prospect. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2012, 28, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, B.; Ramirez, J.I.; Flynn, M. The role of familism in the relation between parent–child discord and psychological distress among emerging adults of Mexican descent. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlia, I.; Hasturi, D. Family climate, perception and adolescent’s stress prior to an during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Child Fam. Consum. Stud. 2022, 1, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayle, A.D.; Chung, K.-Y. Revisiting first-year college students’ mattering: Social support, academic stress, and the mattering experience. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2007, 9, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetti, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Seeman, T.E. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 330–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger, R.D.; Conger, K.J.; Martin, M.J. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.D.; Galambos, N.L.; Krahn, H.J. Depression and anger across 25 years: Changing vulnerabilities in the VSA model. J. Marriage Fam. 2014, 28, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Zumbo, B. Life satisfaction in early adolescence: Personal, neighborhood, school, family, and peer influences. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leto, I.V.; Petrenko, E.N.; Slobodskaya, H.R. Life satisfaction in Russian primary schoolchildren: Links with personality and family environment. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1893–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.E.; Pérez, S.M.; Ochoa, G.M.; Ruiz, D.M.; Estévez, E. Clima familiar, clima escolar y satisfacción con la vida en adolescentes. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2008, 25, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Belea, M.; Calauz, A. Social support: A factor of protection against stress during adolescence. J. Res. Soc. Interv. 2019, 67, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, D.; Estevez, E.; Murgui, S.; Musitu, G. Relacion entre el clima familiar y el clima escolar: El rol de la empatía, la actitud hacia la autoridad y la conducta violenta en la adolescencia. Int. J. Psychol. Ther. 2009, 9, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Zubizarreta, A.; Calvete, E.; Hankin, B.L. Punitive Parenting Style and Psychological Problems in Childhood: The Moderating Role of Warmth and Temperament. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, C.; Beckert, T.; Marsee, I. Well-being and Substance Use in Emerging Adulthood: The Role of Individual and Family Factors in Childhood and Adolescence. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 3853–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vautero, J.; Taveira, M.D.; Silva, A.D.; Fouad, N.A. Family influence on academic and life satisfaction: A social cognitive perspective. J. Career Dev. 2020, 48, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaña-Moral, M.T.; Gavín-Chocano, Ó.; Pérez-Navío, E.; Martínez-Serrano, M. Relationship among Perceived Stress Life Satisfaction and Academic Performance of Education Sciences Students of the University of Jaén after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. The relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction of soldiers: Moderating effects of gratitude. Asia-Pac. Converg. Res. Interchang. 2019, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Yan, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Deng, R.; Zhang, W.; Yao, J. Perceived stress and life satisfaction among elderly migrants in China: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 978499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, E.; Wachholtz, A. The effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction: The mediating effect of self-efficacy. Chongsonyonhak Yongu 2016, 23, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarei, S.; Fooladvand, K. Family functioning and life satisfaction among female university students during COVID-19 outbreak: The mediating role of hope and resilience. BMC Women Health 2022, 22, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, S.; Shahzadi, S.; Furgan, M. Family Social Capital and Life Satisfaction Among Working Women: Mediating Role of Work–Life Balance and Psychological Stress. Int. Assoc. Marriage Fam. Couns. 2023, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, M.; Tułecka, M. Family Functioning and Life Satisfaction: The Mediatory Role of Emotional Intelligence. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 4, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n = 920 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) Mean (SD) | 21.32 (3.54) | |

| Sex [n, (%)] | Men | 420 (45.7%) |

| Women | 500 (54.3%) | |

| Branch of knowledge [n, (%)] | Arts and Humanities | 98 (10.7%) |

| Sciences and Health Sciences | 153 (16.6%) | |

| Social and Legal Sciences | 457 (49.7%) | |

| Engineering and Architecture | 212 (23%) | |

| Course [n, (%)] | First | 240 (26.1%) |

| Second | 261 (28.4%) | |

| Third | 251 (27.3%) | |

| Fourth | 168 (18.3%) |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PS | 26.44 | 7.44 | - | |||||

| 2. LS | 18.45 | 3.41 | −0.491 *** | - | ||||

| 3. CCF | 2.41 | 0.43 | 0.160 *** | −152 *** | - | |||

| 4. SCC | 2.92 | 0.37 | 0.056 | 0.091 ** | 0.421 *** | - | ||

| 5. DEFO | 3.07 | 0.52 | −0.031 | 0.210 *** | 0.187 *** | 0.535 *** | - | |

| 6. VCF | 1.9 | 0.72 | 0.070 * | −153 *** | 0.318 *** | 0.071 * | −0.100 ** | - |

| Model Path | Effect | Boot-LLCI | Boot-ULCI | SE/BootSE * | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||||

| PS → LS | −0.214 | −0.239 | −0.188 | 0.013 | −16.598 | 0.000 |

| Indirect effects (**) | ||||||

| PS → CCF → LS | −0.009 | −0.016 | −0.003 | 0.003 | Y | |

| PS → SCC → LS | 0.002 | −0.000 | 0.006 | 0.002 | N | |

| PS → DEFO → LS | −0.002 | −0.007 | 0.002 | 0.002 | N | |

| PS → VCF → LS | −0.002 | −0.006 | −0.001 | 0.001 | Y | |

| Total indirect effects | −0.011 | −0.020 | −0.003 | 0.004 | Y | |

| Total effects | −0.225 | −0.251 | −0.199 | 0.013 | −17.074 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morales Almeida, P.; Nunes, C. Family Climate as a Mediator of the Relationship between Stress and Life Satisfaction: A Study with Young University Students. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070559

Morales Almeida P, Nunes C. Family Climate as a Mediator of the Relationship between Stress and Life Satisfaction: A Study with Young University Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(7):559. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070559

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorales Almeida, Paula, and Cristina Nunes. 2024. "Family Climate as a Mediator of the Relationship between Stress and Life Satisfaction: A Study with Young University Students" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 7: 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070559

APA StyleMorales Almeida, P., & Nunes, C. (2024). Family Climate as a Mediator of the Relationship between Stress and Life Satisfaction: A Study with Young University Students. Behavioral Sciences, 14(7), 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14070559