Exploring Loneliness among Korean Adults: A Concept Mapping Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Formulation of the Prompt

2.2. Statement Generation

2.2.1. In-Depth Interviews

2.2.2. Extracting Elements of the Concept

2.3. Structuring of Statements

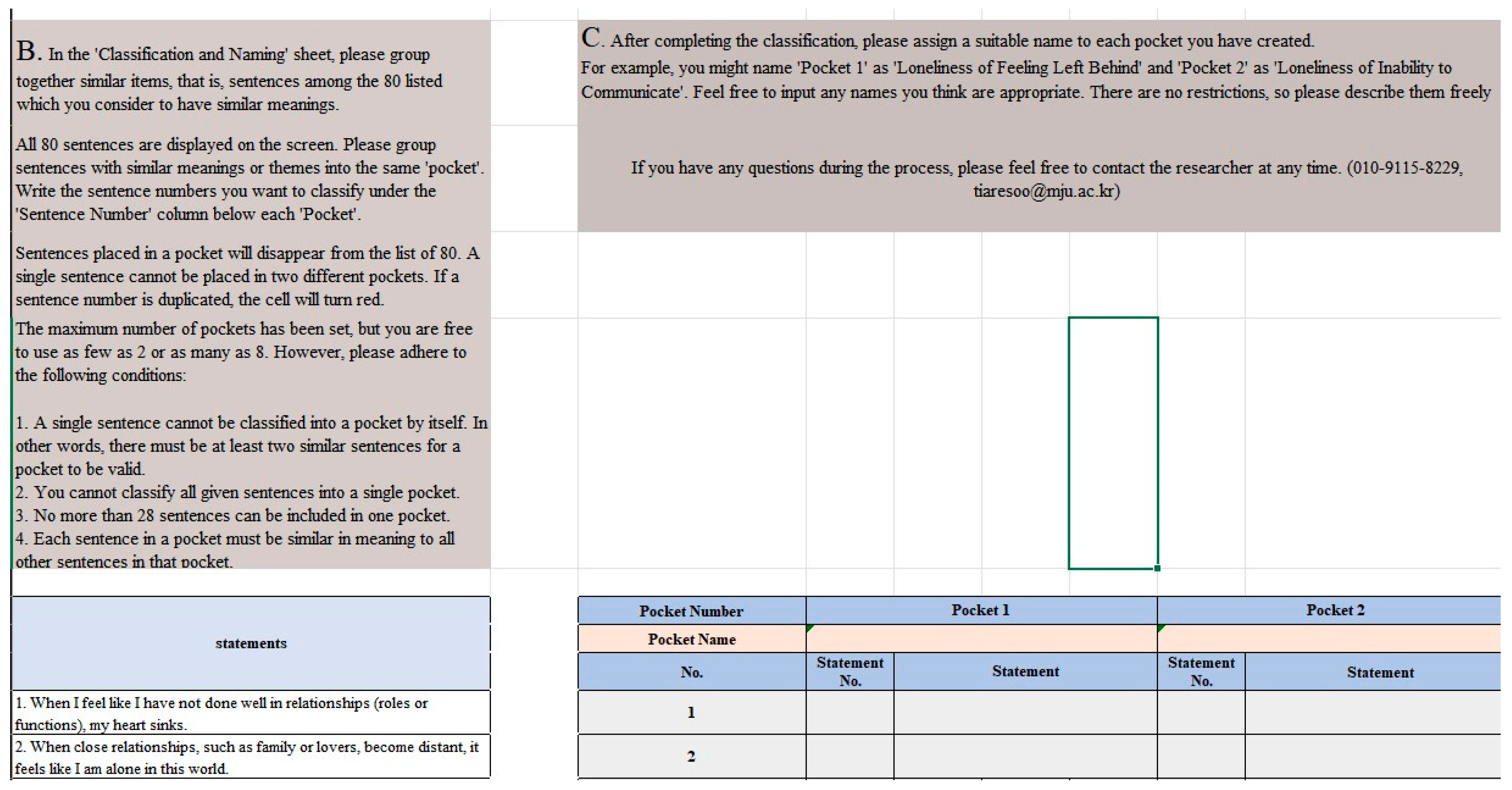

Sorting for Similarities and Rating for Relevance

2.4. Concept-Mapping Analysis

2.4.1. Multidimensional Scaling Analysis

2.4.2. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

2.5. Interpretation of the Map

3. Results

3.1. Dimensions of Loneliness Experienced by Korean Adults

3.2. Clusters and Concept Map of Loneliness Experienced by Korean Adults

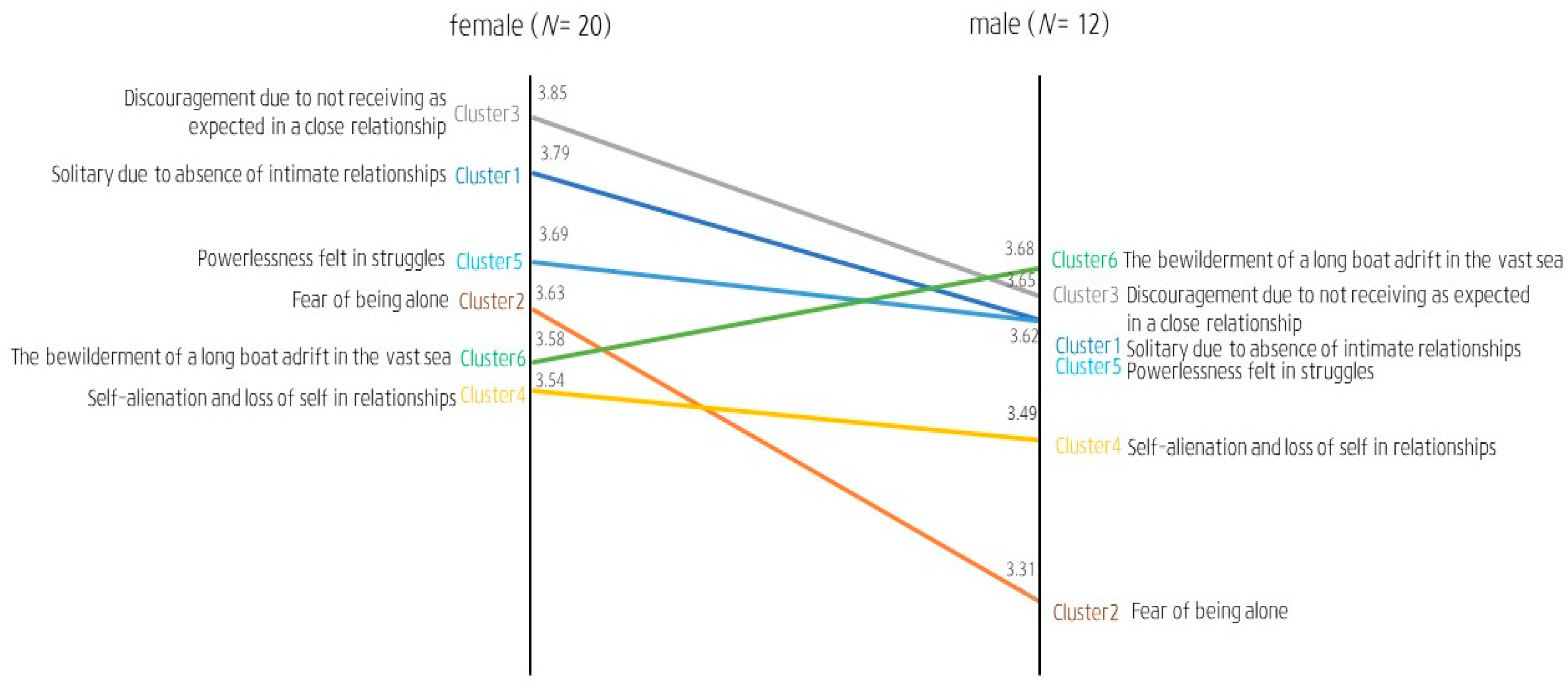

3.3. Pattern-Matching Analysis of Loneliness by Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. Feeling of Lack Experienced by Koreans and Its Focus

4.2. Loneliness Due to Relationship with Self, Others, and the World

4.3. Relevance of Elements of Loneliness

4.4. Implications for Practice, Advocacy, Education and Training, and Research

4.5. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Cluster | Statement | Relevance M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Emotional distress due to actual or anticipated absence of connection in relationships | 3.64 (0.97) |

| Sub-cluster 1 | Solitude due to the absence of intimate relationships | 3.73 (0.96) |

| 12 | There is no one I can deeply share my thoughts and feelings with. | 4.44 (0.80) |

| 14 | I do not have anyone to lean on or rely on. | 4.38 (0.87) |

| 13 | When difficult times arise, there is no one to help me. | 4.16 (0.88) |

| 11 | I feel lonely because I want comfort but cannot express my feelings. | 4.16 (0.63) |

| 52 | There is a void due to the death of parents, family members, etc. | 3.97 (1.03) |

| 44 | In the organization I belong to, there is no one to share my feelings with. | 3.88 (0.75) |

| 80 | When I am alone on important days (e.g., birthdays), I feel like I am inadequate. | 3.88 (1.07) |

| 16 | I feel empty when I am away from loved ones. | 3.84 (0.88) |

| 41 | When I cannot relate to or participate in the topic of conversation at gatherings, I feel like I am the odd one out. | 3.81 (0.90) |

| 61 | There is no one who values me as much as I value myself. | 3.56 (1.05) |

| 77 | There are not many people to share my interests and hobbies with. | 3.50 (0.92) |

| 38 | I feel lonely because I cannot engage in physical intimacy with my loved one. | 3.41 (1.13) |

| 17 | There is limited interaction or contact with people within the organization. | 3.31 (1.03) |

| Sub-cluster 2 | Fear of being alone | 3.51 (0.98) |

| 62 | I feel like I have to deal with my emptiness or difficult emotions on my own. | 4.28 (0.77) |

| 51 | It feels empty because it seems like there is no one in this world to trust. | 3.81 (0.86) |

| 37 | Even though I have been living diligently, I suddenly feel powerless and alone. | 3.75 (0.95) |

| 48 | It feels like a precious presence will disappear from my side. | 3.72 (1.05) |

| 43 | There is no one at work who supports me. | 3.72 (0.92) |

| 46 | It feels like I cannot belong or establish roots anywhere. | 3.69 (0.78) |

| 69 | It feels like I will not have a family and will be alone. | 3.38 (1.21) |

| Cluster 2 | Emotional distance from oneself or from others in a relationship | 3.74 (0.91) |

| Sub-cluster 1 | Dissatisfaction in a relationship due to unmet expectations | 3.78 (0.91) |

| 15 | It feels like I have no one on my side if those close to me do not show interest or care about important matters. | 4.25 (0.67) |

| 2 | When close relationships, such as family or lovers, become distant, it feels like I am alone in this world. | 4.25 (0.80) |

| 7 | If people I thought were close to me do not fully understand me, it feels like they are distant. | 4.09 (0.86) |

| 25 | It is disappointing when the other person does not care about me as much as I care about them. | 4.06 (0.84) |

| 78 | Someone who was once very close (e.g., children, a very close friend) is gradually becoming distant. | 4.00 (1.05) |

| 33 | When those close to me do not believe what I say, I feel like I’m disconnected from everyone. | 3.88 (0.83) |

| 26 | It feels like the other person does not give their heart to me as much as I give mine to them. | 3.84 (0.85) |

| 71 | When the other person does not focus on me, it feels like I am not valuable. | 3.84 (1.02) |

| 5 | It feels empty when we stop having heart-to-heart conversations in a familiar relationship. | 3.75 (1.11) |

| 63 | I distance myself because I fear getting hurt more if l rely on others. | 3.72 (1.02) |

| 67 | When I am going through a tough time and the other person cannot fully understand or help me, it feels lonely. | 3.59 (0.84) |

| 8 | Even if I express my feelings honestly, it feels like the other person will not understand. | 3.53 (0.95) |

| 68 | It feels lonely when loved ones feel lonely or hurt because of me. | 3.53 (1.95) |

| Sub-cluster 2 | Self-alienation and loss of self in relationships | 3.52 (0.88) |

| 58 | It is disheartening when I feel like my true thoughts and emotions are not respected. | 4.19 (0.90) |

| 72 | Over time, the expectations of people and the yearning for relationships decrease. | 3.72 (0.81) |

| 59 | It feels futile when I ignore my own needs to consider others. | 3.44 (0.91) |

| 9 | I feel bitter when I cannot express my own hardships due to a desire to support the other person. | 3.53 (0.92) |

| 66 | When loved ones are going through a tough time and I can only watch because I can’t help them, it creates distance between people. | 3.22 (0.79) |

| 57 | In close relationships (family, lovers, etc.), when everything has to be shared, it feels like I am disappearing. | 3.03 (0.92) |

| Cluster 3 | Powerlessness and emptiness due to being directionless | 3.65 (0.99) |

| Sub-cluster 1 | Powerlessness felt during difficulties | 3.78 (0.99) |

| 29 | I feel worthless when my worth is not acknowledged. | 4.38 (0.79) |

| 74 | When I have not achieved anything, I feel worthless. | 4.25 (0.92) |

| 1 | When I feel like I have not done well in relationships (roles or functions), my heart sinks. | 4.03 (0.82) |

| 30 | It feels desolate because it seems like everyone else is happier than me. | 3.94 (0.98) |

| 32 | Others seem to have much more than me. | 3.91 (1.03) |

| 28 | When it feels like my peers are receiving more recognition, I feel left behind. | 3.84 (1.05) |

| 55 | When I receive negative evaluations, I feel like a failure. | 3.81 (0.82) |

| 39 | When things do not go as planned in my relationships or life, it feels like my life is not my own. | 3.81 (0.86) |

| 75 | I feel like my valuable actions or things are taken lightly or not respected. | 3.75 (0.88) |

| 54 | It seems like neither society nor my family needs me. | 3.75 (1.02) |

| 53 | I feel like a useless person in this society. | 3.63 (0.94) |

| 73 | Sometimes, not only others, but I also do not believe in myself. | 3.63 (1.01) |

| 34 | When I cannot fit into the mainstream, I feel useless. | 3.56 (0.95) |

| 50 | In a rapidly changing world, it feels like I am standing still alone. | 3.56 (1.08) |

| 31 | When I see happy people on social media, it feels like I am the only one falling behind. | 3.53 (0.95) |

| Sub-cluster 2 | Bewilderment like a boat adrift in a vast sea | 3.63 (1.04) |

| 45 | It is bewildering not knowing where I am heading in the face of an uncertain future. | 4.06 (0.98) |

| 21 | Being too busy, I miss out on precious and important things. | 3.88 (1.04) |

| 22 | I am so busy that I do not even have time to focus on my own thoughts and feelings. | 3.81 (1.09) |

| 60 | When I look back on my life, it feels like I can never go back to those times. | 3.59 (1.13) |

| 47 | The idea of someday dying and disappearing from this world feels empty. | 3.19 (1.00) |

References

- Rokach, A. The Correlates of Loneliness; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, V.H. Together: Loneliness, Health and What Happens When We Find Connection; Profile Books: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, S.; Jeffrey, K.; Michaelson, J. The Cost of Loneliness to UK Employers; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Korea. Social Indicators of South Koreans; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Korea. Social Indicators of South Koreans; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Korea. Social Indicators of South Koreans; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.W. Does Korea Need a Minister for Loneliness? Korea Research Planning Report Series; Korea Research, 2018.

- Goodwin, R.; Cook, O.; Yung, Y. Loneliness and life satisfaction among three cultural groups. Pers. Relatsh. 2001, 8, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, A.; Iqbal, N. Loneliness matters: A theoretical review of prevalence in adulthood. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2019, 7, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Berntson, G.G.; Larsen, J.T.; Poehlmann, K.M.; Ito, T.A. The psychophysiology of emotion. In Handbook of Emotions; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, T.; Danese, A.; Wertz, J.; Odgers, C.L.; Ambler, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: A behavioural genetic analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.K. The influences of loneliness, anger and suicidal ideation on juvenile delinquency. Korean Soc. Wellness 2016, 11, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D.; Seol, K.O. A longitudinal analysis of changes in loneliness, sense of control and binge eating symptoms among young adult women. Korean J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 31, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebesutani, C.; Fierstein, M.; Viana, A.G.; Trent, L.; Young, J.; Sprung, M. The role of loneliness in the relationship between anxiety and depression in clinical and school-based youth. Psychol. Schools 2015, 52, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B.; Koval, P.; Erbas, Y.; Houben, M.; Pe, M.; Kuppens, P. Sad and alone: Social expectancies for experiencing negative emotions are linked to feelings of loneliness. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2015, 6, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, N.I.; Lieberman, M.D.; Williams, K.D. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science 2003, 302, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bound Alberti, F. This “modern epidemic”: Loneliness as an emotion cluster and a neglected subject in the history of emotions. Emot. Rev. 2018, 10, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwein, B.H.; Cristiani, R. What is the History of Emotions? Politi Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, L.M.; Gullone, E. The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 26, 695–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnick, P.M. Feeling lonely: Theoretical perspectives. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2005, 18, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, L.; Victor, C.; Meads, C.; Daykin, N.; Tomlinson, A.; Lane, J.; Gray, K.; Golding, A. A conceptual review of loneliness in adults: Qualitative evidence synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.; Peplau, L.A.; Ferguson, M.L. Developing a measure of loneliness. J. Personal. Assess. 1978, 42, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, S.R.; Hymel, S.; Renshaw, P.D. Loneliness in children. Child. Dev. 1984, 55, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong Gierveld, J. A review of loneliness: Concept and definitions, determinants, and consequences. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 1998, 8, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiTommaso, E.; Spinner, B. The development and initial validation of the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA). Personal. Individ. Differ. 1993, 14, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.S. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell-Deutsch, B. The conceptualization and measurement of childhood loneliness. In Loneliness in Childhood and Adolescence; Rotenberg, K.J., Hymel, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Landmann, H.; Rohmann, A. When loneliness dimensions drift apart: Emotional, social, and physical loneliness during the COVID-19 lockdown and its associations with age, personality, stress, and well-being. Int. J. Psychol. 2022, 57, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöberg, M.; Beck, I.; Rasmussen, B.H.; Edberg, A.K. Being disconnected from life: Meanings of existential loneliness as narrated by frail older people. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, Y.S.; An, S.J.; Kim, H.; Ko, S. Review on the conceptual definition and measurement of loneliness experienced among Koreans. Korean J. Psychol. Gen. 2020, 39, 205–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.Y.; Tuval-Mashiach, R. The social construction of loneliness: An integrative conceptualization. J. Constr. Psychol. 2015, 28, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, E.Y.; Waite, L.J. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, D.; Peplau, L.A. Theoretical approaches to loneliness. In Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy; Peplau, L.A., Perlman, D., Eds.; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.G. Cultural relativism and countercultural relativism. J. Cross-Cult. Stud. 1993, 1, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; French, D.C. Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annul. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S. Cognition and motivation in emotion. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, Q.H. Mindsponge Theory; Walter de Greyter GbmH: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Brown, J.D.; Deng, C.; Oakes, M.A. Self-esteem and culture: Differences in cognitive self-evaluations or affective self-regard? Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 10, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, A.; Lackovic-Grgin, K.; Penezic, Z.; Soric, I. The effects of culture on the causes of loneliness. Psychology 2000, 37, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rokach, A.; Orzeck, T.; Cripps, J.; Lackovic-Grgin, K.; Penezic, Z. The effects of culture on the meaning of loneliness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 53, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, T.G.; Havens, B.; De Jong Gierveld, J. Loneliness among older adults in the Netherlands, Italy, and Canada: A multifaceted comparison. Can. J. Aging 2004, 23, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualter, P.; Vanhalst, J.; Harris, R.; Van Roekel, E.; Lodder, G.; Bangee, M.; Maes, M.; Verhagen, M. Loneliness across the life span. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Moon, H.; Choi, E.L. Impact of SNS addition tendency on university student’s loneliness: Moderating effect of social support. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2013, 10, 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- McWhirter, B.T. Loneliness: A review of current literature, with implications for counseling and research. J. Couns. Dev. 1990, 68, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, R.P. Concept mapping the client’s perspective on counseling alliance formation. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.; Trochim, W.M. Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McNeish, R.; Walker, C.; Massey, O.; Tran, Q. Using Concept Mapping to Operationalize Mental Well-Being for Men and Boys. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 66, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Hwang, S.H. The validity of the Korean-UCLA Loneliness Scale version 3. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2019, 26, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.W. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Personal. Assess. 1996, 66, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.A.; Miller, R.S.; Riger, A.L.; Dill, J.C.; Sedikides, C. Behavioral and characterological attributional styles as predictors of depression and loneliness: Review, refinement, and test. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C.; Crawford, L.E.; Ernst, J.M.; Burleson, M.H.; Kowalewski, R.B.; Malarkey, W.B.; Van Cauter, E.; Berntson, G.G. Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morahan-Martin, J.; Schumacher, P. Loneliness and social uses of the Internet. Comput. Human Behav. 2003, 19, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Won, J.W.; Baek, H.S.; Park, K.J.; Kim, B.S.; Choi, H.R.; Hong, Y.H. Influence of loneliness on cognitive decline among elderly living alone in Korea: One year prospective study. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2008, 29, 695–701. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H.W.; Yang, N.M. Clustering by the levels of adult attachment, self-determined solitude, and loneliness, and group differences in depression, stress coping strategy, satisfaction with life among college students. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2019, 31, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M.; Victor, C.; Hammond, C.; Eccles, A.; Richins, M.T.; Qualter, P. Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 169, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, G.R. Loneliness and coping among tertiary-level adult cancer patients in the home. Cancer Nurs. 1990, 13, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, J.A.; Biegel, D.E.; Shafran, R. Concept mapping in mental health: Uses and adaptations. Eval. Program Plan. 2000, 23, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J. Meta-analytic overview of concept mapping methodology in Korean counseling psychology research. Korean J. Couns. 2019, 20, 179–199. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld, J.; Kamphuis, F. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1985, 9, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verity, L.; Schellekens, T.; Adam, T.; Sillis, F.; Majorano, M.; Wigelsworth, M.; Qualter, P.; Peters, B.; Stajniak, S.; Maes, M. Tell me about loneliness: Interviews with young people about what loneliness is and how to cope with it. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younger, J.B. The alienation of the sufferer. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1995, 17, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, F.W.; Takane, Y.; Lewyckyj, R. ALSCAL: A nonmetric multidimensional scaling program with several individual-differences options. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. 1978, 10, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. Understanding Motivation and Emotion; Kim, A.Y.; Doh, S.Y.; Shin, T.S.; Lee, W.G.; Lee, E.J.; Jang, H.S., Translators. Original Work Published 1992; Bakhaksa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C. Cluster analysis. In Reading and Understanding More Multivariate Statistics; Grimm, L.G., Yarnold, P.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 147–205. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W. The Reliability of Concept Mapping [Paper Presentation]. In Proceedings of the Annual conference of the American Evaluation Association, Dallas, TX, USA, 3–6 November 1993; Volume 6. Available online: https://www.billtrochim.net/research/Reliable/reliable.htm (accessed on 10 January 2022.).

- Park, K.B. Multivariate Analysis; Hakjisa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M.F.; Cox, M.A. Multidimensional Scaling; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal, J.B. Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrika 1964, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaisen, M.; Thorsen, K. Who are lonely? Loneliness in different age groups (18–81 years old), using two measures of loneliness. Int. J. Aging Human Dev. 2014, 78, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, V. Key concept: Loneliness. Philos. Psychiatr. Psychol. 2021, 28, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Inumiya, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Zhang, W. The application of culture bounded self-construal model: A comparative study between three countries in northeast Asia. Korean J. Psychol. Gen. 2009, 28, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, V.E. What is meant by meaning? J. Exist. 1966, 7, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen, L. A Philosophy of Loneliness; Lee, S.J., Translator. Original Text Published 2017; Cheongmi: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, J.G. Loneliness, its nature and forms: An existential perspective. Man World 1995, 28, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Kim, S.J. A study on the loneliness of the elderly at home. J. Wellness 2021, 16, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, K.D.M. The rise of living alone and loneliness in history. Soc. Hist. 2017, 42, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.W. The uses of loneliness in adolescence. In Loneliness in Childhood and Adolescence; Rotenberg, K.J., Hymel, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 244–262. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Patrick, W. Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection; Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D.; Stokes, M.; Firth, L.; Hayashi, Y.; Cummins, R. Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 45, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, S.; Grippo, A.J.; London, S.; Goossens, L.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.S.; Son, H.H.; Park, H.K. Relationship between relationship-orientation, unification, and actions for building an educational community: The mediating effect of a sense of community. J. Eco-Early Child. Educ. Care 2019, 18, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.J. Psychology of the Korean People; Hakjisa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.; Ryu, S.A. The difference of cultural emotions in unfair situation in Korea, China, Japan, and the U.S. Korean Psychol. J. Cult. Soc. Issues 2018, 24, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.A. Buroum: An analysis of benign envy in Korea. Korean J. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2009, 23, 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Meece, J.L.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Hoyle, R.H. Students’ goal orientations and cognitive engagement in classroom activities. J. Educ. Psychol. 1988, 80, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E.; Choi, Y.; Choi, M.; Park, S.; Seo, Y. The relationship among loneliness, interpersonal sensitivity, and facebook addition. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2014, 26, 713–736. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, J.S.; Suh, E.K. Happiness in Korea: Who is happy and when? Korean J. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2011, 25, 143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, T. Loneliness at adolescence. In Loneliness: A sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy; Peplau, L.A., Perlman, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 269–290. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C.E. Loneliness. Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Lim, D.H.; Kang, M. Precariousness and happiness of South Korean young adults: The mediating effects of uncertainty and disempowerment. Korean Assoc. Soc. Policy 2017, 24, 87–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, H.W.; Cha, K.H. Analyses on the construct of psychological well-being (PWB) of Korean male and female adults. J. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2001, 15, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J.; Kwak, Y.K.; Jeon, J.H. A study of Social Unrest in Korea: For Young People; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2020; Available online: http://repository.kihasa.re.kr/handle/201002/37345 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Lee, S.Y.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.Y. Analysis of precariousness in Korean youth labour market. J. Critic. Soc. Welfare 2017, 54, 487–521. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney, J.A.; Noller, P.; Hanrahan, M. Assessing adult attachment and couple relationships. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications; Cassidy, J., Shaver, P., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 355–377. [Google Scholar]

- Josephs, R.A.; Markus, H.R.; Tafarodi, R.W. Gender and self-esteem. J. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 1992, 63, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.; Oyserman, D. Gender and thought: The role of the self-concept. In Gender and Thought: Psychological Perspectives; Crawford, M., Gentry, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 100–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hawton, A.; Green, C.; Dickens, A.P.; Richards, S.H.; Taylor, R.S.; Edwards, R.; Greaves, C.J.; Campbell, J.L. The impact of social isolation on the health status and health-related quality of life of older people. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steed, L.; Boldy, D.; Grenade, L.; Iredell, H. The demographics of loneliness among older people in Perth, Western Australia. Australas. J. Ageing 2007, 26, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Qualter, P.; Barreto, M.; Stegen, H.; Dury, S. Loneliness in older migrants: Exploring the role of cultural differences in their loneliness experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitayama, S.; Park, J. Emotion and biological health: The socio-cultural moderation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 17, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, L.S.; Paivio, S.C. Working with Emotions in Psychotherapy; Lee, H.P., Translator. Original Work Published 1997; Hakjisa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shiota, M.N.; Kalat, J.W. Emotion, 2nd ed.; Min, K.H.; Lee, O.K.; Lee, J.I.; Kim, M.H.; Kim, M.C., Translators. Original Work Published 2011; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheek, J.M.; Busch, C.M. The influence of shyness on loneliness in a new situation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 7, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C.; McCusker, C.; Hui, C.H. Multimethod probes of individualism and collectivism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.R. Measuring shame: The Internalized Shame Scale. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 1987, 4, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, R.E. Self-focused attention in clinical disorders: Review and a conceptual model. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y. The relationship between self-focused attention and emotion regulation. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2011, 23, 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, P.J.; Eichstaedt, J.; Phillips, A.G. Are rumination and reflection types of self-focused attention? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartre, J.P.; Mairet, P. Existentialism and Humanism; Methuen: London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rokach, A. The experience of loneliness: A tri-level model. J. Psychol. 1988, 122, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Han, J.H. A phenomenological study on existential self-consciousness experiences of participants in existential group counseling. J. Asia Pac. Couns. 2016, 17, 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, B. Authenticity and our basic existential dilemmas. Existent. Anal. J. Soc. Existent. Anal. 2007, 18, 288–296. [Google Scholar]

- Masi, C.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 15, 219–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, A. Solitude: A Return to the Self; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, L.M.; French, R.D.S.; Anderson, C.A. The prototype of a lonely person. In Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy; Peplau, L.A., Perlman, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Riger, S. Measuring subjectivities: “Concept mapping as a feminist research method: Examining the community response to rape”. Psychol. Women Q. 1999, 23, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstjuns, I.; Moser, A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brower, R.S.; Abolafia, M.Y.; Carr, J.B. On improving qualitative methods in public administration research. Adm. Soc. 2000, 32, 363–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, S.-J.; Seo, Y.-S. Exploring Loneliness among Korean Adults: A Concept Mapping Approach. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060492

An S-J, Seo Y-S. Exploring Loneliness among Korean Adults: A Concept Mapping Approach. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):492. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060492

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Soo-Jung, and Young-Seok Seo. 2024. "Exploring Loneliness among Korean Adults: A Concept Mapping Approach" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060492

APA StyleAn, S.-J., & Seo, Y.-S. (2024). Exploring Loneliness among Korean Adults: A Concept Mapping Approach. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060492