Clear Yet Crossed: Athletes’ Retrospective Reports of Coach Violence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Part 1—Quantitative Design

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Questionnaire

2.1.3. Procedure

2.1.4. Statistical Analysis

2.2. Part 2—Qualitative Design

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Procedure

2.2.3. Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

3. Results

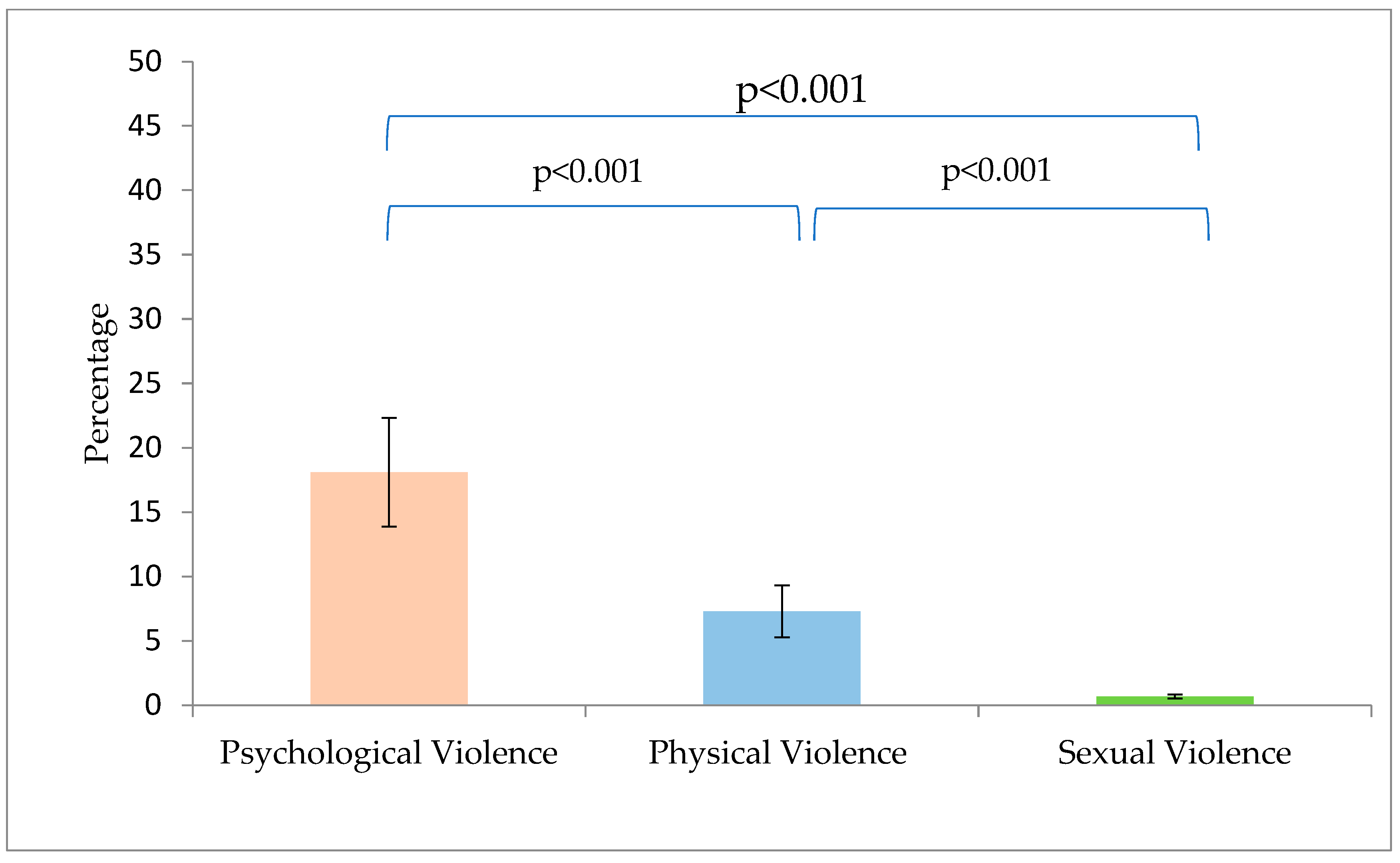

3.1. Part 1—Quantitative Design

3.2. Part 2—Qualitative Design

3.2.1. Theme 1: Psychological Violence

But he would scream at me, terrorize me, swear at me. Later, there was a very, very strong issue of control. Who I could go out with, what I was allowed to say. It was like the ‘thoughts and feelings police’. If you lost a competition but didn’t really seem miserable—in his opinion—then he thought something was wrong with you. You should be sad because you lost and vice versa. If you wear certain clothes then it’s not appropriate, because it attracts too much attention. He brought me into sports at the age of eight, and we finished at the age of 30. We went through three Olympic Games, crises, and breakups. She ignored me every time I said something that didn’t meet her expectations. She actually expected us to be silent. She could ignore me for a whole week, like a punishment… So I learned to always keep my mouth shut.(Nurit)

He would scream so much, until he lost his voice, just because he was mad at something that we had done wrong.(Shir)

When we traveled, he kept my money. He would decide whether to give it to me or not. He used to threaten me and sometimes he even acted on his threats, and we couldn’t buy anything with our own money. In addition to expressing psychological violence, the interviewees spoke of how they coped with such violence, as seen in the following quotes.(Ori)

As a result, I lost my faith in her [the coach]. Training wasn’t fun anymore. But I kept on trying not to disappoint my parents. I retired with the feeling that I had dedicated my life to sports but had nothing to show for it… This was very difficult for me to let go of. I think you can see this even now as I talk about it, I’m still very emotional. I couldn’t talk about it for about a year. I wasn’t ready to talk about sports at all, at all… I also had issues with food, that was a very difficult relationship, I wanted to inhale everything without stopping to breathe. My parents started to worry about me. They would say, ‘You’re eating like a truck’… I simply replied that now that my coach isn’t there anymore, nobody can tell me what or what not to eat. I gained a lot of weight, and I was very upset that I had gained weight but then I didn’t know how to lose it. I was afraid of being hungry… I retired with the feeling that I was nobody, that I was a loser, that I wasn’t successful. I felt that I didn’t know who I was because I hadn’t succeeded. These feelings were with me all the time. Until I slowly started to recover and tried to escape from such associations as much as possible, from such people. The truth is that at first, I constantly needed feedback. Every time I did something, I needed someone to tell me if it’s okay or not. I had lost my self-esteem… There was no me. There was only a robot. I had to rebuild myself, and that was very, very difficult.(Tamar)

3.2.2. Theme 2: Verbal Violence

Screaming like crazy at a young girl for minutes on end because she made a mistake?! That’s overreacting, right? And you would often hear crazy yelling. But you get used to it. You know you’ll be screamed at. You just don’t know when.(Tamar)

You say to yourself, it is what it is, there’s nothing I can do about it. Is there any other way to be on the national team and achieve your dreams? What can you do? He’s the coach. If you don’t want to [put up with it], you can stop. But if you want to move forward and make your dreams come true, then this is the only way.(Shir)

He knows how he behaves. It’s not a secret. Everyone knows it, everyone knows that he loses control and shouts and goes on a rampage and does illogical things… But it’s all part of the sport. He’s the coach. He wants you to succeed, he pushes you. So where’s the line? It’s really problematic.(Nave)

When I was 14, he would always laugh at me because of how I looked. He would tell me not to eat and that if I did eat, I should only eat salad. I was larger than my teammates. He used to call me: a pig, ball, fat, big butt. I couldn’t stand it. I felt humiliated. It was really unpleasant for me, I dedicated my life to swimming. And I really tried to improve, I came to all the training sessions, I never caused any problems. I always did as I was told. I even started running as well, and ate much less, but didn’t lose any weight. I was hungry all the time. Eventually I dropped out of the swimming team.(Noga)

She would humiliate me by imitating me crying. She was disrespectful towards my parents. She humiliated me in front of all the younger girls. But I did nothing. I just took it and took it. I didn’t enjoy the training sessions anymore. Once when a substitute coach arrived, I enjoyed myself so much that I suddenly remembered why I love gymnastics so much.(Tamar)

Whenever we saw him walking angrily down the corridor, no one wanted to even get close to him. No one wanted to accidentally see him. Think of how many hours, days, and weeks we spent with him… and when the atmosphere is so aggressive, you start to feel ill. You carried the fear with you.

He insisted that our lives be devoted to sports. No family distractions, no boyfriends, no work, no school. We had to be sport nuns…(Yael)

3.2.3. Theme 3: Starvation and Food Fattening

She would weigh me four times a day. Before training, after the first training, before the second training, and after the second training. Every single time. One day, the goal was to reach 48 Kg. But if I had reached 48, she would have demanded that I reach 47. It would never end. One day, I weighed 50 kg I think at the beginning of training, so I was supposed to weigh 47 by the end. You have to understand how thin I was… But she just said: ‘You don’t start training until you’re 47 kg, I don’t care how, do whatever you want, hang me, take pills, throw up. I don’t care what you do, you’re not starting until you’re 47 kg. I’m lucky I don’t like to throw up. I said OK. She told me to start running, even though I have stress fractures. I started running, I ran for like an hour. I lost one kilo. Then I only drank water. No food. Just water. But I couldn’t keep running anymore. I was on a treadmill so I started walking. I said to myself, at least I’ll walk, I can’t run. It wasn’t like I was running with a T-shirt and leggings. You need to understand how I was dressed. I was wearing long pants, a short-sleeved shirt, a long-sleeved shirt, a lined jacket, and a coat when she came to check on me. But when she saw that I was walking and not running, she started screaming and swearing at me, like she had completely lost control. She shouted at me to start jumping next to her with the jump rope. So for the next two-and-a-half hours, I jumped rope next to her. I was not allowed to stop!!! My legs were on fire. I couldn’t feel them anymore. It hurt like crazy. After that, she told the personal trainer to take me to run in the sand dunes. It was like that almost every evening. He weighed me and I was 47.7 kg. He was so kind, he just said, ‘Well, without your clothes your weight is OK’.I swear I hadn’t eaten, I wasn’t allowed to drink. She wouldn’t let me drink. She said it makes my muscles swell and makes me heavy.Needed to see me sweat, huge amounts of sweat. So what did I do? I wouldn’t drink all day and then I would come to the room at the end of training and drink 3 L. But then I would feel really heavy, I was gaining 2–3 kg just from the water I drank, and then the next morning, she would weigh me again and ask why I had eaten the night before. She would shout at me that I’m a liar, a thief. And I would try to tell her that I’ve only been drinking, not eating, and then she would scream even more, saying, ‘But I told you not to drink!’. How was I supposed to exist if I couldn’t drink during the day, couldn’t drink at lunchtime, couldn’t drink in the evening, couldn’t drink at night…?At first, I tried really hard to do what she told me to do. She was my mentor, she knows what’s right… I really did what she told me, but it was just impossible to function like that. Absolutely impossible. At breakfast, she would give me one cucumber and an egg. Sometimes I had lunch, sometimes not, depending on my weight. If I was given lunch, it was a salad or even just an apple, and then in the evening… vegetables and maybe some yogurt. I was always hungry. I would think about food all the time, even while training.(Noa)

For years I suffered from eating disorders and from a distorted body image.I gained weight and then had no clue how to lose it…(Noa)

3.2.4. Theme 4: Non-Proportional Punishing

My friend was fooling around before the game. The coach got angry and threw him off the field. I begged him to punish him after the game. He was our leading player. But he just screamed at me too and told me to get off the field. I didn’t play that day. I had been preparing for this game for months, my parents had come especially to see me play. I sat outside feeling very humiliated.(Ofek)

In general, it’s humiliating when you’re a mature person and you’re being yelled at in front of other people, in front of the other competitors. There were loads of comments all the time. Even about other teammates. Like the pants that she was wearing that had to many frills. He [the coach] thought they were attracting too much attention, so he said to her, ‘If you want attention, win some medals. But don’t wear those pants anymore’. Then one day she wore them on purpose, and he just dropped her off in the middle of nowhere while we were on the way to the airport in Berlin! She had to make her own way to the airport!(Ofek)

When I [later] became a coach myself, I knew how not to behave towards my young athletes.(Yam)

At the time, we were very obedient. No one wanted to be punished or thrown off the team. We knew that we depended on him, and he was considered the best.(Gonen)

3.2.5. Theme 5: Physical Violence

I just didn’t do the entrance of the choreography the way she wanted me to. So she gets up, tugs on my arm, and shouts, ‘What did you do?!’. And then she steps on me. She knew I had a stress fracture… I’d had it for about two years, but she stood on me!… There were other little girls in the gymnasium… It was really unpleasant. Then suddenly something occurred to me, and I answered her! For the first time ever, I answered her. I was really angry and I said, ‘Enough is enough!’. She was so shocked that I had even reacted. But then she looked at me and yelled, ‘What did you say?!’.(Tamar)

She took me by the hand just like that and then pushed me. She really shoved me and I fell. And then she started kicking me, and shouted, ‘Get out of here!’. I was so humiliated, so, so humiliated. All the little girls were watching… I just got up, took my bag, and left.

All the time I felt like I wasn’t OK. No matter what I did. During training, the coach would swear at us, shout and humiliate us. He didn’t care that I was in pain. For example, I had stress fractures in my legs. But he thought I was inventing my pain. He would say that I was making it up just so that I wouldn’t have to make an effort. But he knew that I had a stress fracture in my leg. I told him that my leg was hurting. One day I really couldn’t jump because of the pain. When I told him, he asked where the pain was. I thought he was asking because he cared. But he just started standing on my leg—really hard, again and again! He told me that I need to go beyond the pain. And I was really trying to overcome the pain and not think about it.(Ofek)

You could have some kind of injury. A tear, a torn or stretched ligament, or something like that. You know it takes six weeks to heal, let’s say, but if you have a competition or training camp coming up, then you go to compete or train even with your injury. Instead of letting it heal properly. Because you understand that if you don’t, you’ll be out of action for much longer than the six weeks. Because you’ve already missed some competitions that were the basis for further competitions. So you compete like this.(Nir)

Once she got mad at me for being sick, I really didn’t feel well. We were at a training camp and the pool was really cold, I was running a fever of 40. So she told me to get into the water to cool down. She said that I have to take part in the training.(Shahar)

Unless you’re dead or dying… even if you’re really ill, you just stay quiet. Otherwise they’ll say that you’re whining. Even though it’s better to miss one training session, rather than killing your body, but I’m like… I’m telling you, everyone around me, myself included, will come to train even if we’re really ill. Everyone’s afraid to say that they’re not coming.(Ofek)

3.2.6. Theme 6: Sexual Violence

We were in the hot tub, like, after training we usually go into the hot tub, and he [the coach’s son], held on to me and took his penis out. At first I thought it was his toe. I was an innocent 14-year-old. I didn’t know what it was, I’d never seen anything like it in my life. When I eventually realized what it was, I froze, I froze in my place. I couldn’t do anything, I just froze… One of the other girls said that he used to touch her, and suddenly all the girls were sitting down with us, talking about it. He’d done that to many of the girls. It was very comforting to know that we weren’t alone. But we didn’t do anything about it. Nothing.(Noga)

From time to time he would touch me, more and more. It got steadily worse. It started with him touching my genitals. Then he would ask me to play something that requires concentration, and I would be really concentrating on the game with the remote control. And he would start to touch me. Then he would pull me on top of him. At first he was fully clothed, but then very gradually, very gently, he would take his pants off. He would also put cream on. The last time it happened, he took me to his room… and lay me on the bed, and started rubbing himself against me. He almost penetrated… I have a picture in my head of some I of mirror on the wall, and I can see myself crying…(Nave)

I didn’t talk to anyone [about it]. I was so ashamed. I was even ashamed to tell my parents. I was really ashamed, because somehow, I felt like I was guilty. Why? I felt that I was guilty, like, why had I gone into the jacuzzi alone with him? Or what did I expect wearing a bathing suit?(Yonit)

When I talked to my teammates about it, everyone thought he had a kind of deviant profile. You know, like if someone brings something up, then everyone immediately says his name or remembers how he used to behave. They all remember this. If he had been a responsible adult, this wouldn’t have happened. It wasn’t really a secret though. So it should have turned on a warning light for other people in the pool. This stuff went on for about a year.(Shir)

We always have this talk, my friends and I, about the babysitter who looks after my kids. I never let my husband take her home, I always take her home myself. Not because I think my husband will do something to her, but because I don’t want there to be a situation where she may not feel comfortable, or that she might say something that happened or didn’t happen. My friends and I always talk about where the line should be drawn.(Nurit)

When you send a child to a class, you know a certain person or you think you know a certain person. But then it’s someone completely different at the core. That’s how it was with my coach… Today I have serious trust issues and it’s clear to me that it’s based on something from there. I do work on these things, but my first instinct is not to trust the person, not to believe the person who is standing in front of me…(Ori)

I felt that I was like… I was very careful to hide everything… but I felt that… When I was there, it seemed funny and I laughed about it. But then at home, I would sit and think about these things, about how to get out of this situation… I felt like I was living a sort of double life with some kind of mask that I put on in the morning and only took off at night… There were many things that never even crossed my mind as being problematic until after I stopped training. Even then I repressed many things and I am only able to see today. I might suddenly remember a certain situation… It’s really difficult for me.(Yam)

I don’t remember getting out of the car [after training]… I just remember how I would feel five seconds later, because I would just sit on the steps at the entrance to my house and cry. Eventually I would collect myself, wipe away the tears, and go into the house as if nothing had happened. Then I would take a shower, and I remember scrubbing my body really hard. I felt like I really needed to clean myself. Even later, when I started dealing with these things as a more mature person, I would scrub my skin until it hurt whenever I was in a difficult situation.(Noga)

I was afraid to talk about it. I was afraid, I didn’t know… like if I look back on it today, I don’t know if I was afraid of my parents’ reaction, or if I was afraid for my place, or if I was afraid that he would deny everything and I would look like a liar… I don’t know what I was thinking, why I didn’t contact anyone, but I really remember trying to get my family to ask me what had happened or how I felt.

4. Discussion

4.1. Part 1—Quantitative Design

4.2. Part 2—Qualitative Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buecker, S.; Simacek, T.; Ingwersen, B.; Terwiel, S.; Simonsmeier, B.A. Physical activity and subjective well-being in healthy individuals: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2021, 15, 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, S.; Fletcher, D.; Arnold, R.; Ashfield, A.; Harrison, J. Measuring well-being in sport performers: Where are we now and how do we progress? Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1255–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.J.; Campbell, J.P.; Gleeson, M.; Krüger, K.; Nieman, D.C.; Pyne, D.B.; Turner, J.E.; Walsh, N.P. Can exercise affect immune function to increase susceptibility to infection? Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 26, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Brackenridge, C.; Fasting, K.; Kirby, S.; Leahy, T. Protecting Children from Violence in Sport; A Review from Industrialized Countries; UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre: Firenze, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy, M.; Brackenridge, C.; Arrington, M.; Blauwet, C.; Carska-Sheppard, A.; Fasting, K.; Kirby, S.; Leahy, T.; Marks, S.; Martin, K.; et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: Harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, G.; Kidd, B.; Donnelly, P. One step forward, two steps back: The struggle for child protection in canadian sport. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertommen, T.; Kampen, J.; Schipper-van Veldhoven, N.; Uzieblo, K.; Van Den Eede, F. Severe interpersonal violence against children in sport: Associated mental health problems and quality of life in adulthood. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 76, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nite, C.; Nauright, J. Examining institutional work that perpetuates abuse in sport organizations. Sport Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, S.; Fortier, K. Prevalence of interpersonal violence against athletes in the sport context. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 16, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, C.R.; Channon, A. Understanding sports violence: Revisiting foundational explorations. Sport Soc. 2017, 20, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audi, R. Intentionalistic explanations of action. Metaphilosophy 1971, 2, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, J. Violence and Democratic Society; Zed Books: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, E. Violence and violence-control in long-term perspective: ‘Testing’ Elias in relation to war, genocide, crime, punishment and sport. In Violence in Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Imbusch, P. The concept of violence. In International Handbook of Violence Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Language and Symbolic Power; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowsky, M.K. Sports fans, alcohol use, and violent behavior: A sociological review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 19, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutz, M. Athletic participation and the approval and use of violence: A comparison of adolescent males in different sports disciplines. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2012, 9, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaaij, R.; Schaillée, H. Unsanctioned aggression and violence in amateur sport: A multidisciplinary synthesis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 44, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S.; Zach, S. The person who loves me the most is also the person who hurts me the most: Power relations between a single coach and an athlete from the athletes’ point of view. Spirit Sport (Ruach Ha’Sport) 2023, 9, 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, F.; Smits, F.; Knoppers, A. ‘You don’t realize what you see!’: The institutional context of emotional abuse in elite youth sport. Sport Soc. 2017, 20, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, A.E.; Kerr, G. The perceived effects of elite athletes’ experiences of emotional abuse in the coach-athlete relationship. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 11, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervis, M.; Rhind, D.; Luzar, A. Perceptions of emotional abuse in the coach–athlete relationship in youth sport: The influence of competitive level and outcome. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2016, 11, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, G.; Willson, E.; Stirling, A. “It Was the Worst Time in My Life”: The effects of emotionally abusive coaching on female Canadian national team athletes. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2020, 28, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, B.; Kawai, K. Punishing coaching: Bukatsudō and the normalisation of coach violence. Jpn. Forum 2017, 29, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zogg, C.K.; Runquist, E.B., 3rd; Amick, M.; Gilmer, G.; Milroy, J.J.; Wyrick, D.L.; Grimm, K.; Tuakli-Wosornu, Y.A. Experiences of interpersonal violence in sport and perceived coaching style among college athletes. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2350248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marracho, P.; Coelho, E.M.R.T.D.C.; Pereira, A.; Nery, M. Mistreatment behaviours in the Athlete-coach relationship. Retos 2023, 2023, 790–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.; Lundqvist, C. Sexual harassment and abuse in coach–athlete relationships in Sweden. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2017, 14, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Report of the Consultation on Child Abuse Prevention (No. WHO/HSC/PVI/99.1); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, S.; Drummond, M. The (limited) impact of sport policy on parental behaviour in youth sport: A qualitative inquiry in junior Australian football. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2015, 7, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoGuercio, M. Exploring Lived Experience of Abusive Behavior among Youth Hockey Coaches. J. Sports Phys. Educ. Stud. 2022, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raakman, E.; Dorsch, K.; Rhind, D. The development of a typology of abusive coaching behaviours within youth sport. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2010, 5, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M. Masculinity on the menu: Body Slimming and self-starvation as physical culture. In Challenging Myths of Masculinity; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Miles-Chan, J.L.; Isacco, L. Weight cycling practices in sport: A risk factor for later obesity? Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pélissier, L.; Ennequin, G.; Bagot, S.; Pereira, B.; Lachèze, T.; Duclos, M.; Thivel, D.; Miles-Chan, J.; Isacco, L. Lightest weight-class athletes are at higher risk of weight regain: Results from the French-Rapid Weight Loss Questionnaire. Physician Sportsmed. 2022, 51, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeckell, A.S.; Copenhaver, E.A.; Diamond, A.B. Hazing and bullying in athletic culture. In Mental Health in the Athlete; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Gaedicke, S.; Schäfer, A.; Hoffmann, B.; Ohlert, J.; Allroggen, M.; Hartmann-Tews, I.; Rulofs, B. Sexual violence and the coach–athlete relationship: A scoping review from sport sociological and sport psychological perspectives. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 643–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. I Was Hit So Many Times, I Can’t Count. 2020. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/07/20/i-was-hitso-many-times-i-cant-count/abuse-child-athletes-japan (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Stoltenborgh, M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Alink, L.R.A.; Ijzendoorn, M.H. The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abus. Rev. 2015, 24, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Hartill, M. Safeguarding, Child Protection and Abuse in Sport: International Perspectives in Research, Policy and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brackenridge, C.H.; Rhind, D. Child protection in sport: Reflections on thirty years of science and activism. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mayoh, J.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Toward a conceptualization of mixed methods phenomenological research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2015, 9, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Johnson, R.B.; Collins, K.M. Call for mixed analysis: A philosophical framework for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approaches 2009, 3, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, S.; Fortier, K.; Vaillancourt-Morel, M.P.; Lessard, G.; Goulet, C.; Demers, G.; Paradis, H.; Hartill, M. Development and initial factor validation of the Violence Toward Athletes Questionnaire (VTAQ) in a sample of young athletes. Loisir et Société/Soc. Leis. 2019, 42, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, A.C.; Swider, B.W.; Kwon, S.H. Back-translation practices in organizational research: Avoiding loss in translation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 108, 699–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazeley, P. Analysing qualitative data: More than ‘identifying themes’. Malays. J. Qual. Res. 2009, 2, 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Anney, V.N. Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: Looking at trustworthiness criteria. J. Emerg. Trends Educ. Res. Policy Stud. 2014, 5, 272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.; Trent, A. Validity in qualitative research revisited. Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector-Mersel, G. Narrative research: Time for a paradigm. Narrat. Inq. 2010, 20, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Premises, principles, and practices in qualitative research: Revisiting the foundations. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 976–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fejgin, N.; Hanegby, R. Gender and cultural bias in perceptions of sexual harassment in sport. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2001, 36, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Law for Preventing Sexual Harassment. 1998. Available online: https://www.nevo.co.il/law_html/law00/72507.htm (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- State Comptroller Report. (2018–2019). Applying the Law. Available online: https://www.mevaker.gov.il/sites/DigitalLibrary/Pages/Reports/3285-2.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1 (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Ericsson, K.A.; Prietula, M.J.; Cokely, E.T. The making of an expert. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hassmén, P.; Kenttä, G.; Hjälm, S.; Lundkvist, E.; Gustafsson, H. Burnout symptoms and recovery processes in eight elite soccer coaches over 10 years. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2019, 14, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.L.; Zhang, T. The roles of coaches, peers, and parents in athletes’ basic psychological needs: A mixed-studies review. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2019, 14, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazou, S.; Ntoumanis, N.; Duda, J.L. Predicting young athletes’ motivational indices as a function of their perceptions of the coach-and peer-created climate. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2006, 7, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagün, E. Self-confidence level in professional athletes; an examination of exposure to violence, branch and socio-demographic aspects. J. Hum. Sci. 2014, 11, 744–753. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, S.; Vaillancourt-Morel, M.P. Magnitude and risk factors for interpersonal violence experienced by Canadian teenagers in the sport context. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2021, 45, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, E.; Brown, L.; Jones, I. Elite athletes’ experience of coping with emotional abuse in the coach–athlete relationship. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2017, 29, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.Y.; Li, X. Behind an Accelerated Scientific Research Career: Dynamic Interplay of Endogenous and Exogenous Forces in Talent Development. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | 1 Never | 2 Rarely (1–2 Times) | 3 Some-Times (3–10 Times) | 4 Very Often (>10 Times) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shook, pushed, grabbed, or threw you | 84.5 | 11.2 | 2.3 | 2 |

| 2 | Threw an object directly at you | 88.2 | 8.1 | 3.0 | 0.7 |

| 3 | Hit you with the hand (for example, slaps) | 92.0 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 0.9 |

| 4 | Punched or kicked you | 97.0 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 5 | Hit you with an object (for example, sports equipment) | 91.1 | 6.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| 6 | Tried to strangle you | 98.0 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.2 |

| 7 | Hit or threw objects that were not aimed directly at you (e.g., water bottles, pens) | 78.0 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 2.0 |

| 8 | Forced you/instructed you to injure an opposing player | 90.5 | 6.4 | 2.0 | 1.1 |

| 9 | Forced you/instructed you to humiliate or mock an opponent | 92.0 | 6.1 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| 10 | Forced you/instructed you to threaten or hurt an opponent | 92.0 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| 11 | Allowed you to injure an opposing player (with a punch, sports equipment, etc.) in a competition, without intervening | 93.6 | 5.2 | 1.2 | / |

| 12 | Allowed you to humiliate or mock an opponent in a competition, without interfering | 90.7 | 6.1 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

| 13 | Allowed you to threaten or hurt an opponent in a competition without intervening | 91.8 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 0.7 |

| 14 | Threatened to leave/abandon you | 88.9 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 1.3 |

| 15 | Threatened to harm you | 91.4 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 0.7 |

| 16 | Threatened to harm someone or something you love | 95.2 | 3.4 | 1.4 | / |

| 17 | Yelled at you and insulted you, humiliated you, and mocked you | 59.5 | 23.0 | 11.4 | 6.1 |

| 18 | Criticized you excessively (e.g., about your performance or your attitude) | 50.2 | 23.6 | 18.9 | 7.3 |

| 19 | Expelled or suspended you | 72.5 | 20.9 | 4.6 | 2.0 |

| 20 | Locked you in a closed room or tried to limit your freedom of movement (e.g., locking you in the locker room, tying you up) | 97.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | / |

| 21 | Asked you to limit or reduce your social connections (with friends, romantic partners, or family member) to enable you to invest more of yourself in your sports | 77.0 | 15.9 | 5.9 | 1.1 |

| 22 | Ignored you or treated you with indifference (e.g., refused to talk to you, ignored your existence) | 66.6 | 20.5 | 9.1 | 3.9 |

| 23 | Forced you/instructed you to do extra high-intensity and excessive training until you were exhausted | 72.5 | 15.2 | 8.9 | 3.4 |

| 24 | Forced you/instructed you to exercise while injured despite having a medical opinion to the contrary | 77.0 | 13.0 | 6.6 | 3.4 |

| 25 | Forced you/instructed you to perform movements or technical actions that are more difficult than you are capable of (physically or psychologically) that had or could have had negative consequences on your health and safety | 78.2 | 16.4 | 3.4 | 2.0 |

| 26 | Asked you to use prohibited substances to reach the desired weight for the sport (fasting, vomiting, pills) | 96.8 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| 27 | Asked you to use prohibited substances to improve performance (steroids, hormones) | 97.1 | 1.1 | 0.2 | / |

| 28 | Knew that you had used prohibited substances to reach the desired weight for the industry | 98.2 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| 29 | Knew that you had used prohibited substances to improve performance | 98.6 | 0.5 | 0.9 | / |

| 30 | Asked you to stop going to school or suspend your studies in order to devote yourself to sports | 88.2 | 7.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 31 | Made rude, insulting comments that made you uncomfortable about your sex life, your private life, or your physical appearance (for example, comments about you or your partner’s intimate body parts) | 87.3 | 8.6 | 2.7 | 1.4 |

| 32 | Behaved sexually in a way that made you feel uncomfortable (for example, rubbing you, staring at you, undressing you with their eyes, whistling at you, and massaging you) | 88.2 | 8.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 33 | Watched you or force you to perform a sexual act (touching yourself, themselves, or others) | 94.3 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| 34 | Photographed you while you were having sexual activity (touching yourself, themselves, or others) | 97.7 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Variable | Standardized β (CI) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.05 (−0.15–0.04) | −1.08 | 0.27 |

| Gender | 0.08 (−0.25–3.22) | 1.67 | 0.94 |

| Sport type | −0.13 (−0.75–0.56) | −0.27 | 0.78 |

| Individual/team | 0.23 (−1.30–2.16) | 0.48 | 0.62 |

| Age of retirement | 0.12 (0.01–0.257) | 2.15 | 0.032 * |

| Retirement: yes/no | −0.06 (−2.97–0.59) | −1.30 | 0.19 |

| Achievements | −0.01 (−1.16–0.92) | −0.22 | 0.81 |

| Years of practice | 0.09 (−0.003–0.29) | 1.926 | 0.055 |

| Number of coaches | 0.14 (0.108–0.496) | 3.056 | 0.002 * |

| Occupation | 0.031 (−0.787–1.575) | 0.655 | 0.513 |

| Residence | −0.012(−1.717–1.342) | −0.241 | 0.810 |

| Zone | 0.029 (−0.386–0.716) | 0.0589 | 0.0556 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zach, S.; Guy, S.; Ben-Yechezkel, R.; Grosman-Rimon, L. Clear Yet Crossed: Athletes’ Retrospective Reports of Coach Violence. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060486

Zach S, Guy S, Ben-Yechezkel R, Grosman-Rimon L. Clear Yet Crossed: Athletes’ Retrospective Reports of Coach Violence. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060486

Chicago/Turabian StyleZach, Sima, Shlomit Guy, Rinat Ben-Yechezkel, and Liza Grosman-Rimon. 2024. "Clear Yet Crossed: Athletes’ Retrospective Reports of Coach Violence" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060486

APA StyleZach, S., Guy, S., Ben-Yechezkel, R., & Grosman-Rimon, L. (2024). Clear Yet Crossed: Athletes’ Retrospective Reports of Coach Violence. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060486