Navigating the Grey Zone: The Impact of Legislative Frameworks in North America and Europe on Adolescent Cannabis Use—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

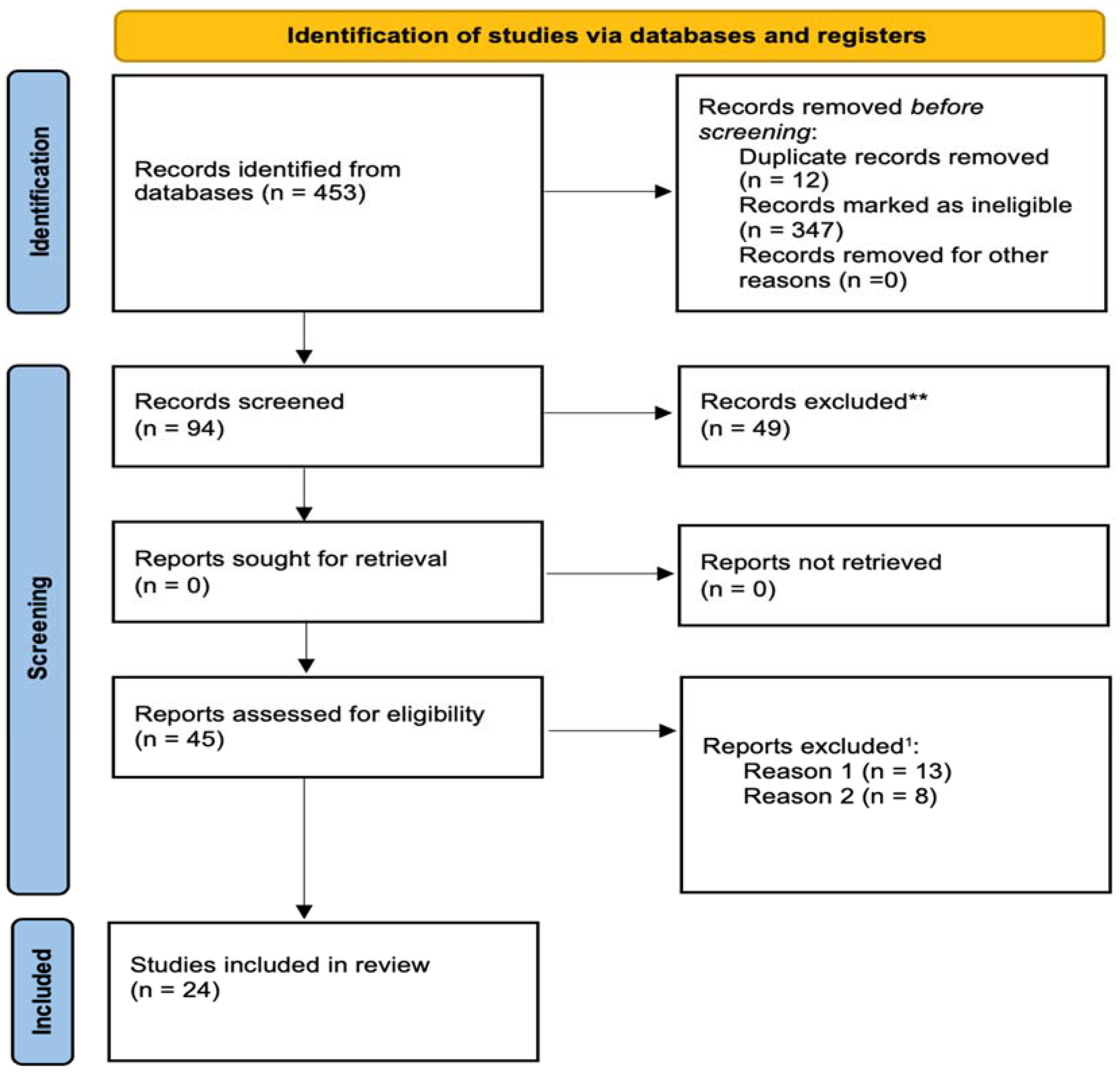

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- All studies involving participants under the age of 25. The age limit was set at 25 due to varying legal adulthood ages across countries, ranging from 18 to 21. Studies commonly sample participants within wide age ranges like 12–25 or 18–24 without differentiating between specific ages. Recognizing this variability, the authors deemed it necessary to include studies up to the age of 25 to ensure comprehensive coverage and account for differences in legal adulthood thresholds worldwide.

- There were no limitations based on the nationality or gender of participants; thus, studies from all countries in North America and Europe, and participants of any gender, were considered.

- Articles that focused solely on or specifically distinguished marijuana use.

- Articles focusing on adults—participants older than 25.

- Articles written in languages other than English. English was selected as it is the common language for both authors to ensure mutual understanding and effective collaboration.

- Articles that focused on the polyuse of substances and did not specifically distinguish marijuana in the results.

- Articles that focused on substances other than marijuana.

2.1.1. Selection Criteria

2.1.2. Data Extraction Tool

- Participant Characteristics:Information regarding participants’ age, gender, nationality, and any relevant demographic factors was systematically coded and categorized to understand the demographic profile of the study populations. Codes included age, gender, nationality, socioeconomic status, and other pertinent demographic variables.

- Cannabis Policy Changes:Any alterations in cannabis policies within the studied regions were meticulously and comprehensively coded and categorized. This encompassed the nature of legalization (medical vs. recreational), types of restrictions imposed, and amendments to existing laws and enforcement measures (e.g., reduction of the severity of the penalties). Codes included the type of policy change (medical/recreational legalization, reduction of the severity of the penalties, or increase of the penalties), restrictions (e.g., age limits), and specific legal amendments.

- Impact of Policy Changes on Cannabis Use:The effects of legislative framework changes on adolescent cannabis use were analyzed in depth. This involved examining shifts in prevalence rates and alterations in patterns of use (e.g., frequency and consumption methods) and identifying any observed trends or correlations. Codes included increase in use, decrease in use, no change in use, changes in consumption patterns, and any emerging trends or correlations observed in the data.

2.1.3. Data

3. Synthesis

3.1. Prevalence According to Policy Changes

3.1.1. Increased Use of Cannabis

Recreational Legalization

Depenalization

Quebec’s Legal Age Adjustment

3.1.2. No Significant Change in Cannabis Use

Recreational Cannabis Legalization

Medical Cannabis Legalization

3.1.3. Mixed Effects

Cannabis Legalization

Decriminalization and Depenalization

Penalty Reduction/Increase

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brewster, D. Problematizing Cannabis. In Cultures of Cannabis Control; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2022; pp. 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chatwin, C. A critical evaluation of the European drug strategy: Has it brought added value to drug policy making at the national level? Int. J. Drug Policy 2013, 24, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanke, M.; Sandberg, S.; Macit, R.; Gülerce, H. Culture matters! Changes in the global landscape of cannabis. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2022, 29, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, Ł.; Sierosławski, J.; Dąbrowska, K. Changes in use and availability of cannabis among adolescents over last two decades. Situation in Poland and selected European countries. Alcohol. Drug Addict./Alkohol. I Narkom. 2018, 31, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, E.; Resce, G.; Brunori, P.; Molinaro, S. Cannabis policy changes and adolescent cannabis use: Evidence from Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, B.P.; Davey, A.; Keenan, E. Deterrence effect of penalties upon adolescent cannabis use. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2023, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotermann, M. Analysis of trends in the prevalence of cannabis use and related metrics in Canada. Health Rep. 2019, 30, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Negura, L. L’analyse de Contenu dans L’étude des Représentations Sociales. SociologieS 2006, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.; Kerr, D.C. Marijuana use trends among college students in states with and without legalization of recreational use: Initial and longer-term changes from 2008 to 2018. Addiction 2020, 115, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpin, S.B.; Brooks-Russell, A.; Ma, M.; James, K.A.; Levinson, A.H. Adolescent marijuana use and perceived ease of access before and after recreational marijuana implementation in Colorado. Subst. Use Misuse 2018, 53, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, B.; Lee, A.; Robinson, T.; Hall, W. An overview of select cannabis use and supply indicators pre-and post-legalization in Canada. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2021, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mæland, R.; Lien, L.; Leonhardt, M. Association between cannabis use and physical health problems in Norwegian adolescents: A cross-sectional study from the youth survey Ungdata. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Mital, S. Changes in youth cannabis use after an increase in cannabis minimum legal age in Quebec, Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2217648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.S.; Haynes, C.; Besharat, A.; Lait, M.C.L.; Green, J.L.; Dart, R.C.; Roosevelt, G. Brief report: Characterization of marijuana use in US college students by state marijuana legalization status as reported to an online survey. Am. J. Addict. 2019, 28, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, C.M.; Newswanger, P.; Santaella-Tenorio, J.; Mauro, P.M.; Carliner, H.; Martins, S.S. Impact of medical marijuana laws on state-level marijuana use by age and gender, 2004–2013. Prev. Sci. 2019, 20, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.A.; Jacobs, L.M.; Vlahov, D.; Spetz, J. Impacts of medical marijuana laws on young Americans across the developmental spectrum. Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusby, J.C.; Westling, E.; Crowley, R.; Light, J.M. Legalization of recreational marijuana and community sales policy in Oregon: Impact on adolescent willingness and intent to use, parent use, and adolescent use. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2018, 32, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.A.; Epstein, M.; Roscoe, J.N.; Oesterle, S.; Kosterman, R.; Hill, K.G. Marijuana legalization and youth marijuana, alcohol, and cigarette use and norms. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, M.; Sarvet, A.L.; Wall, M.; Feng, T.; Keyes, K.M.; Galea, S.; Hasin, D.S. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent use of marijuana and other substances: Alcohol, cigarettes, prescription drugs, and other illicit drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 183, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doggett, A.; Battista, K.; Jiang, Y.; de Groh, M.; Leatherdale, S.T. Patterns of cannabis use among Canadian youth over time; examining changes in mode and frequency using latent transition analysis. Subst. Use Misuse 2022, 57, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, N.; Strong, D.; Myers, M.G.; Correa, J.B.; Tully, L. Post-legalization changes in marijuana use in a sample of young California adults. Addict. Behav. 2021, 115, 106782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckermann, A.M.; Gohari, M.R.; Romano, I.; Leatherdale, S.T. Changes in cannabis use modes among Canadian youth across recreational cannabis legalization: Data from the COMPASS prospective cohort study. Addict. Behav. 2021, 122, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.A.; Goldwater, E.; Stanek, E.J.; Brierley-Bowers, P.; Buchanan, D.; Whitehill, J.M. Prevalence and correlates of cannabis use in Massachusetts after cannabis legalization and before retail sales. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2021, 53, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, D.; Wadsworth, E.; Reid, J.L.; Burkhalter, R. Prevalence and modes of cannabis use among youth in Canada, England, and the US, 2017 to 2019. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 219, 108505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennis, J.; McKeon, T.P.; Stahler, G.J. Recreational cannabis legalization alters associations among cannabis use, perception of risk, and cannabis use disorder treatment for adolescents and young adults. Addict. Behav. 2023, 138, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Mital, S.; Bornstein, S. Short-term effects of recreational cannabis legalization on youth cannabis initiation. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormshak, E.A.; Caruthers, A.S.; Gau, J.M.; Winter, C. The impact of recreational marijuana legalization on rates of use and behavior: A 10-year comparison of two cohorts from high school to young adulthood. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2019, 33, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaičiūnas, T.; Žemaitaitytė, M.; Lange, S.; Štelemėkas, M.; Oja, L.; Petkevičienė, J.; Kowalewska, A.; Pudule, I.; Piksööt, J.; Šmigelskas, K. Trends in Adolescent Substance Use: Analysis of HBSC Data for Four Eastern European Countries, 1994–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, T.; Parolaro, D. Long lasting consequences of cannabis exposure in adolescence. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2008, 286, S108–S113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistella, G.; Fornari, E.; Annoni, J.-M.; Chtioui, H.; Dao, K.; Fabritius, M.; Favrat, B.; Mall, J.-F.; Maeder, P.; Giroud, C. Long-term effects of cannabis on brain structure. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 2041–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W. The costs and benefits of cannabis control policies. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 22, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, C.L.; Mason, M.J.; Langenderfer, J. The shifting landscape of cannabis legalization: Potential benefits and regulatory perspectives. J. Consum. Aff. 2021, 55, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.A.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyshka, E. Applying a social determinants of health perspective to early adolescent cannabis use–An overview. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2013, 20, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, B.P.; Dudovitz, R.N.; Cooper, Z.D.; Tucker, J.S.; Wong, M.D. Adolescent Cannabis Misuse Scale: Longitudinal Associations with Substance Use, Mental Health, and Social Determinants of Health in Early Adulthood. Subst. Use Misuse 2023, 58, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, S.; Caulkins, J.P.; Kleiman, M.A. Controlling underage access to legal cannabis. Case West. Reserve Law Rev. 2014, 65, 541. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.A.; Ilgen, M.A.; Jannausch, M.; Bohnert, K.M. Comparing adults who use cannabis medically with those who use recreationally: Results from a national sample. Addict. Behav. 2016, 61, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgrei, O.R.; Buvik, K.; Tokle, R.; Scheffels, J. Cannabis, youth and social identity: The evolving meaning of cannabis use in adolescence. J. Youth Stud. 2022, 25, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negura, L.; Plante, N. The construction of social reality as a process of representational naturalization. The case of the social representation of drugs. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2021, 51, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Mortel, T.F. Faking it: Social desirability response bias in self-report research. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 25, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z. Cross-sectional studies: Strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations. Chest 2020, 158, S65–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorray, E.L.; Emery, L.F.; Garr-Schultz, A.; Finkel, E.J. “Mostly White, heterosexual couples”: Examining demographic diversity and reporting practices in relationship science research samples. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 125, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, R.; Pacula, R.L. Early evidence of the impact of cannabis legalization on cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and the use of other substances: Findings from state policy evaluations. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2019, 45, 644–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | First Author (Study Countries) | Year(s) of Data Collection | Year of Publication | Sample Characteristics | Source of Data | Type of Legislative Change | Findings | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bae and Kerr [10] (USA, 48 states) | 2008–2018 | 2020 | Undergraduates aged 18–26 years attending college in US states that did (n = 234,669 in seven states) or did not (n = 599,605 in 41 states) enact RML between 2008 and 2018. | Cross-sectional National College Health Assessment Survey | Recreational cannabis legalization. | After adjusting for covariates and state-specific trends, the prevalence of 30-day cannabis use increased more among students exposed to RML, with an odds ratio of 1.23 (95% CI = 1.19–1.28, p < 0.001), and similar trends were observed for frequent use (≥20 days) with an odds ratio of 1.18 (95% CI = 1.10–1.27, p < 0.001). | Not specified. |

| 2 | Harpin et al. [11] (Colorado, USA) | 2013–2014 | 2017 | 6th through 12th grade students 2013 (n = 12,240) and 2014 (n = 11,931) who were surveyed in 40 schools (19, 9th–12th grade high schools and 21, 6th–8th grade middle schools, some combined). | Healthy Kids Colorado Survey | Recreational cannabis legalization. | No significant changes were observed in the prevalence of ongoing use of cannabis, past 30-day use. Significant increase in perception of easy access to cannabis. | The persistence of cannabis use may be due to the prohibition for minors under 21 and the likelihood that many had already started using before legalization. Communities with more lenient views on cannabis may have higher use rates due to local ordinances and dispensaries, but behavior change could still occur with time despite media attention to cannabis policy. |

| 3 | Fischer et al. [12] (Canada) | 2017–2020 | 2021 | NCS: Sample size (n) = 12,000, Age range: 15 and older. CCS: Sample size (n) > 10,000, Age range: 16 and older. CSTADS: Targeted at grades 7–12, mostly ages 13–18. CAMH Monitor: Focus on adults aged 18 and over in Ontario. ICPS 1: Non-probability sample, ages 16–65. | National Cannabis Survey (NCS) Canadian Cannabis Survey (CCS) Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drugs Survey (CSTADS) The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) International Cannabis Policy Study (ICPS) Ontario Cannabis Store (OCS) | Recreational cannabis legalization. | NCS: the overall prevalence of cannabis use in the past three months increased from 14.9% in 2018 to 20.0% in 2020, with the highest prevalence among those aged 18–24 years. Among respondents aged 15–17, cannabis use fluctuated but did not show significant differences over this period. CCHS: cannabis use in the past 12 months increased from 21.9% in 2018 to 26.9% in 2020, with the age group of 20–24 years exhibiting the highest use. Cannabis use also increased among those aged 16–19 years during this time frame. CSTADS: cannabis use remained steady from 2016/17 to 2018/19, with an increase observed among younger students in grades 7–9 but no change in older students in grades 10–12. All age groups showed increasing trends in cannabis use between 2017 and 2019. | The rise in cannabis consumption has been linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 4 | Rotermann [7] (Canada) | To update long-term trends in 12-month cannabis prevalence from 2004 to 2017. To analyze cannabis consumption patterns using data collected every three months from early 2018 to 2019. | 2019 | CTUMS: (n) = 19,822 to 21,976 CTADS: (n) = 14,565 to 16,349 NCS (Quarterly): (n) = Averaged 5811 respondents. | Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS) Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS) National Cannabis Survey (NCS) | Recreational cannabis legalization. | Between 2004 and 2017, the use of cannabis declined among 15 to 17-year-olds, while it remained consistent among 18 to 24-year-olds. From 2018 to 2019, the frequency of cannabis use in the last three months was notably greater among individuals aged 18 to 24 standing at 34.8%, surpassing the rates observed in other age brackets, ranging from 4% to 24%. | Continual alterations in policies regarding the legalization, regulation, and constraints on non-medical cannabis, alongside the evolving societal acceptance of its use, persist in influencing use trends. |

| 5 | Mæland et al. [13] (Norway) | 2017–2019 | 2022 | Norwegian adolescents from 2017 to 2019, covering about 80% of lower secondary school pupils (aged 13–15) and 50% of upper secondary pupils (aged 16–19). (n) = 249,100 | Norwegian youth survey Ungdata | Depenalization (reduction of the severity of the penalties). | As age increased, so did cannabis consumption from 1.5% (1st year of lower secondary) peaking at 18.9% in the final year of upper secondary education. Additionally, a clear correlation emerged between lower family income and higher cannabis use, with figures ranging from 7.3% in consistently well-off families to 24.0% in financially struggling households. | Age and socioeconomic status. |

| 6 | Benedetti et al. [5] (20 European countries: Croatia, Czech Rep., Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Rep., Slovenia, Sweden, Ukraine) (13 countries where laws were changed and 7 countries that served as a control group) | 1999–2015 | 2021 | Students who turn 16 years of age in the given survey year. Croatia (n) = 14,667 Czech Rep. (n) = 16,876 Denmark (n) = 8512 Finland (n) = 18,881 France (n) = 12,214 Greece (n) = 15,834 Hungary (n) = 14,151 Iceland (n) = 14,112 Italy (n) = 26,665 Latvia (n) = 10,852 Malta (n) = 17,035 Netherlands (n) = 10,397 Norway (n) = 15,294 Poland (n) = 28,521 Portugal (n) = 14,616 Romania (n) = 14,747 Slovak Rep. (n) = 10,971 Slovenia (n) = 14,550 Sweden (n) = 14,399 Ukraine (n) = 13,590 | European School Survey Project (ESPAD) | Decriminalization (change in the status of cannabis use from a criminal to a non-criminal offence), depenalization (reduction of the severity of the penalties) and increase of the penalties (either civil or criminal). | Significant changes in the prevalence of cannabis use are associated with only two specific policy changes: depenalization through minor case closure facilitation of the closure of minor cases leads to an increase (6.6 percentage points) in cannabis use, while an increase in non-prison penalties results in a decrease (3.3 percentage points). These associations are consistent across all users, but no significant effects were observed for frequent cannabis users. | Certain reforms in cannabis policies were linked to notable shifts in prevalence. |

| 7 | Wieczorek et al. [4] (Poland’s results were compared to those obtained in specific European countries, namely the Czech Republic, France, Finland, and Ukraine.) | 1995, 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011 and 2015. | 2018 | 15- to 16-year-olds (n) Poland 2015 = 11,822 (n) Czech Republic 2015 = 2738 (n) Finland 2015 = 4049 (n) France 2015 = 2714 (n) Ukraine 2015 = 2350 | European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Drugs (ESPAD) | Reduction of the severity of the penalties. | Between 1995 and 2015, experimental cannabis use among 15- to 16-year-olds in Poland rose threefold with 25% having tried it by 2015. Nearly 20% were occasional users, and close to 10% used it in the last 30 days before the study. Compared to other countries, Poland saw a significant increase while most others showed a decline in cannabis use, except for the Czech Republic, where the decrease began in 2007. | Individual psychosocial factors such as familiarity with drug sources and influence from peers and family members who use drugs seem to have a more substantial impact on drug prevalence compared to legal regulations governing drug supply and demand. |

| 8 | Nguyen and Mital [14] (Canada) | 2018–2020 | 2022 | 15–20 years old (n) = 1005 | National Cannabis Surveys | Increase in minimum legal age for recreational cannabis use in Quebec. | Despite the policy change, cannabis consumption did rise; however, the escalation in cannabis use among 18- to 20-year-olds was 51% less in Quebec compared to other provinces, while there was no noticeable shift in cannabis use among 15- to 17-year-olds. | The data indicate that while some youth may have resorted to the illegal market, the decrease in legal cannabis use outweighed the increase in illegal consumption. |

| 9 | Wang et al. [15] (USA) | 2014–2015 | 2019 | College students 18< median age was 24 years. (n) = 7105 | Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance (RADARS) | Medical cannabis legalization. Recreational cannabis legalization. Non-legal states. | In states where recreational cannabis is permitted, 28% of college students have reported recent cannabis use, exceeding the rates observed in both non-legalized states (22%) and states with medical cannabis legalization (25%). The difference between states with medical cannabis legalization and those without legalization is statistically significant (p < 0.001). The likelihood of cannabis use is higher in both medical (OR: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.09–1.38) and recreational (OR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.07–1.97) legalized states compared to non-legalized states. Additionally, students residing in states with medical cannabis legalization show a greater inclination for cannabis use compared to their counterparts in non-legalized states. | Decline in risk perception and the shift in public opinion are substantial factors contributing to the increased use of cannabis. |

| 10 | Smyth et al. [6] (Portugal, UK, Italy, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Finland, Poland, Denmark.) | 1995–2017 | 2023 | 15–16-year-old school children (n) = 700,000 students | European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Drugs (ESPAD) | Penalty reduction. Penalty increase. | In eight out of ten cases analyzed, changes in penalties for cannabis use were aligned with deterrence theory, suggesting that stricter penalties were associated with a decrease in cannabis prevalence while more lenient penalties were correlated with increased use. The likelihood of these patterns occurring by chance was calculated at 0.05. The median change in prevalence around policy shifts was 21%, with instances of both increases and decreases in cannabis use observed. | Reducing penalties could potentially lead to slight upticks in adolescent cannabis use and, as a result, elevate the associated risks and harms linked to cannabis. |

| 11 | Mauro et al. [16] (USA) | 2004–2013 | 2019 | 12–17 years old (n) = 17,500 18–25 years old (n) = 17,500 26 and older (n) = 18,000 | National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) | Medical cannabis legalization. | MML enactment did not impact cannabis use among 12–17-year-olds. For 18–25-year-olds, MML did not affect past-month use, but daily use increased notably among men after MML enactment. | MMLs might affect cannabis availability more for men, possibly as an alcohol substitute. Additionally, more men might use cannabis medicinally or to replace opioid use in this age group. |

| 12 | Schmidt et al. [17] (USA) | 2019 | 12–25 years old (n) = 450,300 | National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) | Medical cannabis legalization. | Living in a state where medical cannabis was legalized did not correlate with recent cannabis use among early adolescents, late adolescents, or young adults. However, young adults in these states were notably more prone to starting cannabis use within the past year. | Adolescents at high-school age exhibit a unique susceptibility to social cues, potentially leading to increased experimentation with drugs. Moreover, in states where enforcement of medical cannabis regulations is comparatively lenient, young adults might demonstrate greater willingness to try cannabis due to their perception of reduced arrest risk or a generally diminished perception of the drug’s risks. | |

| 13 | Rusby et al. [18] (USA) | 2014–2015 | 2017 | Average age 14.4 (n) = 444 Parents (age not specify) (n) = 343 | Online questionnaires | Recreational cannabis legalization. | In places where sales were restricted, new users were less likely to start with cannabis, but in areas where it was legalized, more non-users expressed an interest. For existing young users, legalization correlated with increased use. Communities banning sales saw a higher increase in cannabis use among young users. Essentially, recreational cannabis legalization did not prompt new users, but it increased consumption among existing users. Legalization did not have an effect on parental use. | The prevailing rejection of recreational cannabis legalization in communities where its sale is banned by policy likely had an impact on the attitudes of young individuals, influenced by these community norms. |

| 14 | Bailey et al. [19] (USA) | 2002–2011 2015–2018 | 2020 | 10–20 years old (n) = 281 youth | Seattle Social Development Project—The Intergenerational Project (SSDP-TIP) | Recreational cannabis legalization. | The legalization of nonmedical cannabis was associated with a notably increased chance of self-reported past-year cannabis use (AOR = 6.85, p = 0.001) and alcohol consumption (AOR 3.38, p = 0.034) among young individuals. However, this legalization did not show a significant link to past-year cigarette use (AOR = 2.43, p = 0.279) or a lower perception of harm from cannabis use (AOR = 1.50, p = 0.236) among youth aged 10 to 20 years. | After nonmedical legalization, there is still a connection between lower perceived harm and increased adolescent cannabis use. |

| 15 | Cerdá et al. [20] (USA) | 1991–2015 | 2017 | 8th, 10th, and 12th graders (n) = 1,179,372 8th graders (n) = 423,899 10th graders (n) = 386,596 12th graders (n) = 368,877 | Monitoring the Future (MTF) | Medical cannabis legalization. | The effects of enacting MML varied across different grades. After its enactment, 8th graders showed decreased use of cannabis. For 10th graders, there was no noticeable impact on substance use following MML implementation. However, among 12th graders, the use of cannabis remained largely unchanged. | When laws permitting medical cannabis are enacted, there might be more public communication regarding the dangers associated with adolescents using cannabis. Eighth graders may be more affected by these cautionary messages compared to other age groups, particularly in relation to cannabis use. Furthermore, parents of younger adolescents might be more inclined to monitor their children’s substance use after these laws come into effect. Research suggests that parental impact is most significant during early adolescence but tends to decrease as adolescents mature. |

| 16 | Doggett et al. [21] (Canada) | 2017–2019 | 2022 | Grades 9–12 (n) = 18,824 | Comparative Policy Analysis for Sustainable Societies (COMPASS) | Recreational cannabis legalization. | Over the course of the study, there was a noticeable inclination among youth to increase the frequency of their cannabis consumption. Moreover, individuals predominantly engaged in cannabis smoking at the initial assessment were observed to transition towards employing multiple modes of cannabis consumption. | It is widely acknowledged that as young individuals age, there is a natural inclination towards engaging in substance-use behaviors. This is compounded by the prevailing understanding from research suggesting a lack of awareness among youth regarding cannabis edibles. Furthermore, young people express a preference for alternative modes of cannabis consumption due to a perception of these methods as being “healthier” choices. |

| 17 | Doran et al. [22] (USA) | 2015–2016 | 2020 | 18–24 years old (n) = 563 | Longitudinal study | Recreational cannabis legalization. | The frequency of cannabis use remained consistent over time, even after legalization. More frequent use was linked to younger age and self-identification as white (p < 0.001), a trend that persisted post-legalization. The frequency of cannabis use was influenced by gender (p < 0.001), indicating an increase in use among women and a decrease among men as time progressed. | Females seem to have a heightened responsiveness to the pleasurable effects of cannabis consumption, potentially making them more susceptible to increased use post-initiation or in situations where obstacles to use are decreased. |

| 18 | Zuckermann et al. [23] (Canada) | 2012–2013 2017–2018 | 2022 | Grade 9–12 students (n) = 230,404 | Comparative Policy Analysis for Sustainable Societies (COMPASS) | Recreational cannabis legalization. | Following a consistent decline in youth cannabis use over the span of several years, there seems to have been a gradual upturn in cannabis consumption among this demographic, particularly in the wake of discussions regarding cannabis legalization. This increase poses elevated risks for certain subsets of the youth population. | In Canada, indicators suggest a normalization of cannabis use, likely due to increased accessibility. This is notably true for young people, especially female students, whose historically stigmatized cannabis use has been affected more. With legalization, access to and normalization of diverse cannabis products are expected to rise. |

| 19 | Evans et al. [24] (USA) | 2017 | 2020 | 18< (n) = 3022 | Cross-sectional mail and web-based survey. | Recreational cannabis legalization. | In Massachusetts, a study revealed that men were more inclined than women to use cannabis, as were individuals aged 18 to 20 in comparison to those aged 21 to 25. | The increased reported use of cannabis in Massachusetts could be due to evolving public opinions and changes in laws and policies related to cannabis, potentially influencing adolescents’ perception of risk and increasing their likelihood of use. |

| 20 | Hammond et al. [25] (Canada, England, USA) | 2017–2019 | 2021 | 16- to 19-year-old Canada (n) = 11,779 England (n) = 11,117 USA (n) = 11,869 | Cross-sectional online surveys. | Recreational cannabis legalization. Medical cannabis legalization. Recreational cannabis legalization. | The use of cannabis was more common in Canada and the US compared to England across all years and saw a more substantial increase between 2017 and 2019 (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Specifically among those who had used cannabis in the past 30 days, the prevalence of vaping oils/liquids and the use of cannabis extracts (oil, wax, and shatter) rose in all countries, with notably higher rates in Canada and the US. | The study found mixed evidence regarding the impact of cannabis legalization on youth. While cannabis use was more prevalent in places where medical cannabis is legal, these differences primarily reflected pre-existing trends. The impact of recreational cannabis legalization appeared mixed, partly due to the recent nature of these changes and the time required to establish legal retail markets. |

| 21 | Mennis et al. [26] (USA) | 2008–2019 | 2022 | 12–25 (n) = 1155 | National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Treatment Episode Dataset—Admissions (TEDS-A) | Recreational cannabis legalization. | Following the legalization of recreational cannabis, there was an increase in the prevalence of past-month cannabis use among adolescents and young adults; | A stronger connection was observed between lower perception of the risk of harm and higher prevalence of cannabis use among both adolescents and young adults. |

| 22 | Nguyen et al. [27] (Canada) | CTUMS 1999–2012 CTADS and CTNS 2013–2017 and 2018 | 2022 | 15 years and older CTUMS (n) = 20,000 CTADS (n) = 15,000 CTNS (n) = 8500 grades 6–12 YSS (n) = 40,000 | Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Surveys (CTUMS) Canadian Tobacco Alcohol & Drugs Surveys (CTADS) Canadian Tobacco & Nicotine Survey (CTNS) Youth Smoking Survey (YSS) | Recreational cannabis legalization. | While the overall prevalence of youth cannabis use remained unchanged, there was a 69% increase in cannabis initiation following legalization. | The environmental and social settings impact how young individuals view the risks of cannabis and whether they decide to use it. After legalization, there was a delay in the number of years before youth started using cannabis. Additionally, while legalization made cannabis more accessible to young people, it also heightened their perception of its potential harm. |

| 23 | Stormshak et al. [28] (USA) | 2000–2010 2009–2018 | 2019 | Early high school—24 (n) = 1468 | Two longitudinal projects. | Recreational cannabis legalization. | The findings show increased cannabis use among individuals in Sample 2 during their young adult years, coinciding with the introduction of RML in Oregon. Young adults in Sample 2 had 2.12 times higher odds of using cannabis at age 24 compared to those in Sample 1, and they reported more frequent use across multiple time points in young adulthood. Overall, these results suggest that young adults after RML are more likely to use cannabis compared to their counterparts a decade earlier. | Not specified. |

| 24 | Vaičiūnas et al. [29] (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland) | 1994–2018 | 2022 | 15 years old (n) = 42,169 | Health Behaviour in School-aged Children survey | Penalty reduction. | Over the past decade, cannabis use within the 30-day period varied in the Baltic states and Poland. Among males, it fluctuated more (5% to 13%) than among females (2% to 8%). The Baltic states saw an increase in cannabis use (TJT = 38.50, z = 1.651, p = 0.099), while Poland remained stable, showing a sharper decline after 2014 (4–8%, TJT = 4.50, z = 1.083, p = 0.279), albeit not a statistically significant one. From 1994 to 2002, the Baltic states showed a general increase, followed by stability between 2002 and 2010, then declining trends from 2010. Poland had less consistent patterns, with declining trends beginning earlier. The prevalence of cannabis use, measured since 2006, displayed unique fluctuations within and among countries. | The use of cannabis suggests insufficient or ineffective national-level cannabis control policies and enforcement, contributing to its increasing popularity in certain countries, such as Lithuania. |

| Type of Policy Changes | Increase | Decrease | No Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recreational cannabis legalization | |||

| Depenalization |

| ||

| Decriminalization, depenalization, increase in penalties |

|

| |

| Reduction of the severity of the penalties (penalty reduction) |

| ||

| Increase in minimum legal age for recreational cannabis use |

| ||

| Legalization for medical use, Legalization for recreational use, non-legal states |

| ||

| Penalty reduction, penalty increase |

|

| |

| Medical cannabis legalization |

| ||

| Recreational cannabis legalization, medical cannabis legalization |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jablonska, B.; Negura, L. Navigating the Grey Zone: The Impact of Legislative Frameworks in North America and Europe on Adolescent Cannabis Use—A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060484

Jablonska B, Negura L. Navigating the Grey Zone: The Impact of Legislative Frameworks in North America and Europe on Adolescent Cannabis Use—A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):484. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060484

Chicago/Turabian StyleJablonska, Barbara, and Lilian Negura. 2024. "Navigating the Grey Zone: The Impact of Legislative Frameworks in North America and Europe on Adolescent Cannabis Use—A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060484

APA StyleJablonska, B., & Negura, L. (2024). Navigating the Grey Zone: The Impact of Legislative Frameworks in North America and Europe on Adolescent Cannabis Use—A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060484