Abstract

Stressful life events (SLEs) and suicidal ideation (SI) are prevalent in persons with major depression disorder (MDD). Less is known about the underlying role of insomnia symptoms in the association between SLEs and SI. This three-wave prospective cohort study sought to investigate the longitudinal association among SLEs, insomnia symptoms, and SI in persons with MDD. The study population included 511 persons with MDD (mean [SD] age, 28.7 [6.7] years; 67.1% were females). Generalized estimated equations (GEEs) were utilized to explore prospective association among exposure of SLEs, insomnia symptoms, and SI. Additionally, a structural equation model (SEM) was employed to estimate the longitudinal mediating effect of insomnia symptoms in the relationship between SLEs and SI. Our study demonstrated that cumulative SLEs were determined to be longitudinally associated with SI in persons with MDD. We further observed that the association between SLEs and SI was significantly mediated by insomnia symptoms. Clinicians assessing persons with MDD, especially those with the history of SLE, could carefully evaluate and promptly treat insomnia symptoms as part of personalized assessment of their depressive illness, thereby achieving early prevention and intervention for suicidal behaviors in persons with MDD.

1. Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is an increasingly serious public health issue [1] and is associated with suicidal behavior [2]. An estimated 90% of persons who die by suicide suffer from one or more mental diseases, with MDD accounting for 59–87% of all reported suicides [2]. Suicidal ideation (SI) is the main precondition of suicidal act [3] and represents an elevated risk of future suicide [4]. A recent meta-analysis of 53,598 persons with MDD reported that the overall prevalence of SI was 37.7% [2] and the rate is increasing [5]. Furthermore, one-fifth of persons with MDD and SI developed a future suicide attempt [6]. Therefore, identifying persons with MDD who are at high risk of SI early has important clinical implications [7].

The integrated motivational–volitional (IMV) model of suicidality describes that individual vulnerabilities confer increased risk for developing SI when activated by the presence of stressors [8]. Stressful life events (SLEs) are common stressors for suicide [9]. SLEs refer to significant incidents that occur abruptly and provoke strong psychological responses in individuals [10]. However, the current evidence on the association between SLEs and SI requires larger epidemiological confirmation.

First, conclusions about the cumulative number of SLEs or the effect of high perceived stress of SLEs on SI were inconsistent. Longitudinal studies in adults with depression have found that it was individuals’ high perception of stress rather than the number of SLEs that increased the risk of suicidal behavior [11]. Longitudinal studies in college students have found an association between high perceived stress and SI [12]. However, Wang et al. also reported positive associations between the number of SLEs and SI [13].

Second, prior studies have investigated risk factors associated with suicidal behaviors in different populations, including specific stressors such as childhood trauma [14,15,16], interpersonal stress [17,18], bullying [19], violence [20], and so on. However, there is limited research examining and comparing different types and periods of stressors comprehensively within the same study, which makes it difficult to identify what life events affect persons with MDD the most.

Trauma-induced insomnia may be a precursor to other disabling post-traumatic complications. The stress-psychopathological model suggests that SLEs are associated with suicidal behavior, as well as psychopathological factors that may also influence the association between SLEs and SI [21]. For example, SLEs may be predisposing factors for insomnia which may bridge the association between SLEs and SI [22]. Short et al. also reported that adults who have experienced trauma were twice as likely to develop insomnia as adults who have not been exposed to trauma [23]. Furthermore, people with persistent insomnia had higher rates of SI [24,25]. Evidence from cross-sectional studies in adolescents and individuals with bipolar disorder has indicated that insomnia symptoms mediated the association between SLEs and SI [26,27]. However, longitudinal studies exploring the potential role of insomnia symptoms between SLEs and SI in persons with MDD are still lacking.

Given that insomnia may be a potentially modifiable risk factor for SI, a better understanding of SLEs and the effects of insomnia symptoms on SI may be helpful for early intervention of suicidal behaviors. Therefore, our aims were to examine (1) the effect of the cumulative number and types of SLEs on SI in persons with MDD and (2) the longitudinal, mediational role of insomnia symptoms in the association between SLEs and SI in persons with MDD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

Data were collected from a subgroup cohort (patient cohort) of Depression Cohort in China (DCC, ChiCTR registry number: 1900022145), which is a large, ongoing cohort study targeting persons aged 18–64 years with MDD and the design of DCC study has been elaborated in a previous study [28]. In the primary study, participants aged 18–64 years were enrolled from a mental health specialty hospital (Shenzhen Kangning Hospital) between June 2020 and September 2022. The inclusion criteria of this study were as follows: (1) diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) confirmed by certified psychiatrists using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5); (2) score on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) ≥ 8 and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) ≥ 5; (3) being capable of understanding research questionnaires and providing informed consent for themselves. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Sun Yat-sen University School of Public Health (Ethical code: L2017044), and written informed consent was acquired from all individuals before participating in the study.

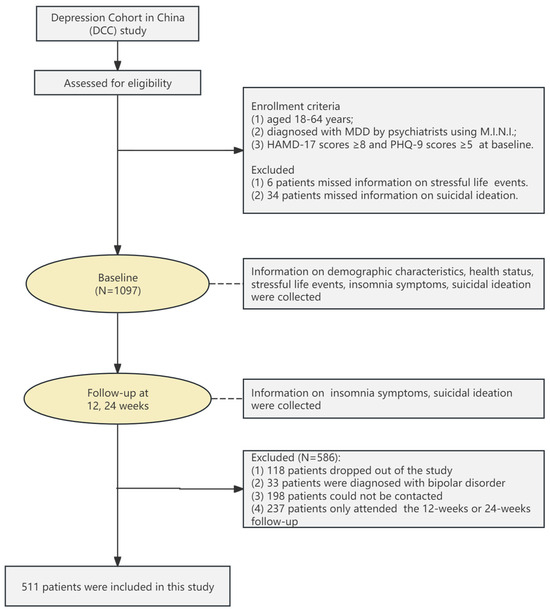

The study flow is depicted in Figure 1. At baseline, participants completed self-reported questionnaires concerning sociodemographic information, health related behaviors, mental health status, SLEs, SI, and insomnia symptoms. Participants were followed up at 12 and 24 weeks and the information about insomnia symptoms and SI was collected. Of the 1097 participants who completed the baseline survey, 118 participants dropped out of the study, 33 participants were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, 198 participants could not be contacted or have incomplete questionnaires, and 237 participants only attended the 12-week or 24-week follow-up, resulting in 511 participants being included in the final analysis.

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment and flow.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Stressful Life Events

The participants’ previous exposure to SLEs was assessed using the stressful life events screening questionnaire (SLESQ) [29], which has demonstrated good reliability and validity [30]. The SLESQ consisted of 13 items, which asked participants to report SLEs that occurred in their daily life. Given the national context of China, following discussions with pertinent experts, we excluded the item “Living in environments akin to armed conflict or war zones where life-threatening dangers could occur at any moment.” Consequently, this decision led to the development of a 12-item Chinese version of the SLESQ, which was utilized in this study to assess exposure to SLEs [31]. A “yes” answer to any of the 12 items was recorded as positive, meaning that they had experienced SLEs. The response to each type of SLE determined whether it occurred and was recoded (0 = did not occur, 1 = occurred), and the cumulative number of SLEs will be accumulated (the total scores ranging from 0–12). Furthermore, due to the significant skewness observed in the measurement of SLEs, with the majority (>75%) of participants experiencing 0 to 3 types of SLEs, we defined 3 levels of SLE exposure: 0 SLE as low exposure, 1 or 2 SLEs as normative exposure, and 3 or more SLEs as high exposure. This classification aimed to ensure a relatively even distribution across groups [32]. Additionally, the SLESQ was utilized at baseline and showed acceptable internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach’s α = 0.70).

2.2.2. Suicidal Ideation

The severity of SI in the latest week was measured by the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSSI) [33]. This self-report instrument includes 19 items that are scored based on a 3-point Likert scale (score range, 0–2, 0 = “I have no wish to die”; 1 = “I have a weak wish to die”; 2 = “I have a moderate-to-strong wish to die”). The intensity of SI is assessed by the first 5 items. The risk of suicide is evaluated based on items 6 to 19, which determine the likelihood of a participant with SI actually attempting suicide. Items 6–19 are only completed if the respondent rates items 4 or 5 with a score of 1 or greater, and thus, we had more complete data for the first 5 items. Consequently, in this study, SI was assessed by the first 5 items and higher scores representing higher levels of SI. Participants was considered to be free of SI only when they received a score of 0 for both items 4 and 5. The BSSI was utilized at baseline and at 12 and 24 weeks, and showed good internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach’s α = 0.81 at baseline; Cronbach’s α = 0.85 at 12 weeks; Cronbach’s α = 0.83 at 24 weeks).

2.2.3. Insomnia Symptoms

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) was utilized to evaluate insomnia symptoms and has shown good reliability and validity in Chinese populations [34]. It consists of 7 measurements items that assess difficulty with initiating or maintaining sleep, degree of early awakening, satisfaction with sleep, impact of sleep difficulties on daily routines, distress, and noticeability of sleep disorder to others over the past 2 weeks [35]. The scale employs a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (no problem) to 4 (extremely severe problem). The total scores range from 0 to 28, where higher scores indicate more severe insomnia symptoms. Insomnia symptoms were assessed at baseline and at 12 and 24 weeks and showed good internal consistency in the current study (Cronbach’s α = 0.90 at baseline; Cronbach’s α = 0.93 at 12 weeks; Cronbach’s α = 0.93 at 24 weeks).

2.2.4. Covariates

Factors associated with SLEs or SI were taken into account among persons with MDD. The covariates consist of sociodemographic information, health related behaviors, and mental health status.

Sociodemographic information included gender, age, marriage, education level, employed status, and family monthly income. Health-related behaviors included lifetime smoking, lifetime drinking, and weekly exercise habit. Lifetime smoking, life drinking, and weekly exercise habit were evaluated by the following questions: “Have you ever smoked a cigarette (0 = No; 1 = Yes)? Have you ever consumed at least one alcoholic drink of any kind (0 = No; 1 = Yes)? Do you have a weekly exercise for more than 30 min (0 = No; 1 = Yes)?”. Mental health status included depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and resilience. Depression symptoms and anxiety symptoms were evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81 in this study) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90 in this study), respectively, which have been validated and widely administered in Chinese populations with reliable psychometric properties [36,37]. We dichotomized GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores into measures of moderate or severe anxiety and depression symptoms (total scores ≥10) [38,39]. Resilience was measured with the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC, Cronbach’s α = 0.92 in this study). Considering the cut-point score in the Chinese population [40], a total score of above 60 points indicates good resilience.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

First, descriptive analyses stratified by SLEs were used to describe the sample characteristics, and the data were presented as number (%) and mean (standard deviation, SD). The t tests for continuous variables and the Chi-square tests for categorical variables were performed to compare the differences between the two groups (exposed to and not exposed to SLEs).

Second, generalized estimated equations (GEEs) were employed to explore the longitudinal association of different types and numbers of SLEs with SI before and after adjusting for confounding variables. Factors that were significant in univariate analyses were considered as confounding variables. The results were expressed as adjusted β estimates and 95% confidence intervals. A linear link function for the continuous outcome variable and an unstructured correlation working structure were used in above analysis.

Third, structural equation models (SEMs) using the maximum likelihood (ML) method were employed to test the mediating effects of insomnia symptom on the association between SLEs and SI after adjusting for covariates and SI at baseline. As the variables relating to SLEs, insomnia symptoms, and SI were continuous, the standardized path coefficients, standardized total effects, and standardized indirect effects were reported and the bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained with 1000 bootstraps resamples. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses used IBM SPSS Statistics (V.27, IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA) and Mplus 8.3 (Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics of this study. Among the 511 participants, 66.9% reported experiencing SLEs. The mean (SD) age of the participants was 28.7 (6.7) years, with 67.1% being females. Additionally, 74.2% of the participants were unmarried, 56.9% had an education level of undergraduate or above, 68.9% were employed, and 56.0% reported a household monthly income above CNY 10,000. Compared with the participants who were not exposed to SLEs, the group exposed to SLEs had a higher proportion of smoking behaviors (p < 0.05), more severe insomnia symptoms (p < 0.05), and higher SI scores (p < 0.01). Except for age, gender, and occupation, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between eligible participants and ineligible participants (Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 511 participants.

The proportion of SLEs is presented in Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials. According to the participants’ response on the SLESQ, the proportion of SLEs was higher in being humiliated or discriminated (45.4%), extreme fear or helplessness (42.1%), and childhood physical abuse (18.6) compared to other types of SLE.

3.2. Longitudinal Association of Types of SLEs with SI

As shown in Table 2, the univariate analysis showed that without adjusting for other variables, three or more events and insomnia symptoms were positively associated with SI (p < 0.01). After adjusting for control variables and insomnia symptoms, the multivariable analysis indicated that only three or more events were significantly associated with an elevated risk of SI (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Association between the numbers of SLEs, insomnia symptoms and SI among persons with MDD.

3.3. Longitudinal Association of Types of SLEs with SI

As shown in Table 3, the univariate analysis revealed that bereavement, witnessing a traumatic event, childhood physical abuse, adulthood physical abuse, being threatened, humiliated, or discriminated, and extreme fear or helplessness were all associated with an increased risk of SI (all p < 0.05). After controlling for potential confounding variables, the multivariate analysis indicated that only childhood physical abuse was positively associated with an increased risk of SI (adjusted β estimate = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.02–0.51).

Table 3.

Association between the types of SLEs and SI in unadjusted model and adjusted model.

3.4. Mediating Effects of Insomnia Symptoms

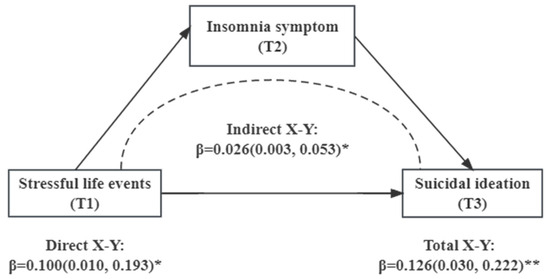

Structural equation models were performed with the total numbers of SLEs at baseline as an independent variable, SI at 24 weeks as a dependent variable, and insomnia symptoms at 12 weeks as a mediating factor. As presented in Table 4, the standardized direct path coefficients of SLEs on SI (standardized β estimate = 0.100, 95% CI = 0.010–0.193) were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Mediating effects of insomnia symptoms on the relationship between SLEs and SI.

The standardized indirect effects of SLEs on SI (standardized β estimate = 0.026, 95% CI = 0.003–0.053) mediated by insomnia symptoms were also statistically significant (p < 0.05) and the mediating effect accounted for 20.6%, indicating that insomnia symptoms partially mediated the associations between SLEs and SI. The results of SEM models depicting the mediating roles of insomnia symptoms in the association between SLEs and SI are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mediating effects of insomnia symptoms on the relationship between SLEs and SI. Note: *: p <0.05; **: p <0.01.

Moreover, the mediating role of insomnia symptoms in the association between specific types of SLEs and SI was examined. However, no significant mediating effect of insomnia symptoms was found in any specific type of SLEs (Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the few longitudinal studies that examines the relationship among SLEs, insomnia symptoms, and SI in persons with MDD. The findings of our study indicate that the larger the cumulative number of SLEs experienced by persons with MDD, the greater the risk of SI. Furthermore, insomnia symptoms may play a longitudinal mediating role in the association between SLEs and SI.

Suicide has been conceptualized as a response to life stressors. Our results suggest that the proportion of persons with MDD exposed to SLEs was relatively high (66.9%), which was in accordance with a separate study conducted in persons with MDD in China (65.6%) [41], but lower than the study conducted in US veterans with MDD (83.0%) [42] as well as a separate study conducted in persons with MDD in Sweden (83.1%) [43].

In addition, as illustrated in Table S1, SI was also common among persons with MDD, with the prevalence of 79.3% in our study. A recent study reported that 66.0% of participants with MDD had SI [7], which was lower than in our study. Methodological differences could account for foregoing discrepancies, including sample composition and various assessment tools of SLEs and SI. Cultural and racial differences in the disclosure of SLEs and SI may also contribute to the differences observed [44]. Overall, considering the high prevalence of both SLEs and SI in persons with MDD, it is crucial to prevent the risk of serious life-threatening outcomes that may be associated with SLEs.

After controlling for demographic characteristics and other psychosocial covariates, the risk of SI increased with the cumulative numbers of SLEs experienced. Our results were consistent with the extant literature that has documented the association between cumulative stressors and SI. For example, cross-sectional studies in people with bipolar disorder have reported that as the number of SLEs experienced over a lifetime increased, affected individuals exhibit more severe psychopathological symptoms, such as more severe anxiety symptoms, higher rates of suicidal tendencies, and greater interpersonal relationship problems [45].

Additionally, a prospective study conducted by Wang et al. found a dose–response relationship between recent SLEs and SI in persons with MDD [13]. A growing body of research has shown that the cumulative effect of psychosocial stressors across the lifespan could increase the likelihood of developing mental health problems [46]. Moreover, it has been reported that the effect of perceived stress of stressors has an independent effect on an individual’s suicide risk, suggesting that the impact of SLEs on suicide risk may be influenced by an individual’s cognitive assessment of life events [11,47,48].

The aforementioned studies emphasize individual variations, suggesting that different individuals respond differently when faced with the same stressor, and these responses can have a significant impact on the problem-solving level of appraisal following an SLE. Furthermore, a systematic review also reported that the magnitude of the effect of multiple SLEs or an individual SLE in a given study is influenced by the type of SLE screening framework [49].

Overall, there are mixed results reported on the effect of the number of SLEs on SI. Our results add and extend the extant literature documenting the longitudinal association between the cumulative number of SLEs and SI. Future studies could explore the effects of the numbers of life events and high perceived stress on SI simultaneously, as well as comparative studies on the effects of single or multiple stressors on SI using validated screening tools.

We also examined how specific stressors across the lifespan may influence the risk of SI. After assessing both childhood and adult stressors, our study reported that traumatic experiences, including childhood physical maltreatment, were particularly associated with the risk of SI. Life adversities during critical developmental stages of life, especially childhood, are associated with more severe and persistent symptoms that negatively affect health outcomes [50]. In addition, it is reported that physical abuse could increase the risk of suicide tendency in adolescents [51], young people [52], persons with MDD [53], bipolar disorder [54], midlife [55], and veterans [42], indicating that childhood physical trauma experiences have a strong impact on suicide risk. The results from our study are in accordance with prior studies, wherein a history of exposure to childhood physical abuse was significantly associated with suicidal behaviors.

Furthermore, our study indicated that SLEs are associated with insomnia symptoms, and may further mediate SI. The results of our study align with the findings of previous cross-sectional studies conducted. For example, Yang et al. reported a negative correlation between childhood maltreatment, sleep duration, and SI among Chinese young adults [56]. A separate cross-sectional study involving 11,831 adolescents indicated that the association between SLEs and suicidality was partially mediated by insomnia [26]. Moreover, a similar association was observed in persons with mental disorders. A study evaluating adolescents with depression has also reported that insomnia is a mediator of childhood physical neglect leading to SI [57]. Palagini et al. (2020) also reported that insomnia symptoms may contribute to the association between early life stressors and SI in adults with bipolar disorder [58]. Moreover, a recent three-year prospective study including 6995 adolescents found that a partial mediation of insomnia 1 year later in the relationship between baseline life stress and SI 2 years later [59], which in accordance with our results herein.

There is yet no clear understanding of the mechanisms subserving the association between SLEs and SI in persons with MDD. One possible mechanism could be the dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. After exposure to stressors, the activation of the HPA axis triggers an excessive release of cortisol [60], which may induce increased sleep reactivity and excessive wakefulness in susceptible individuals, leading to insomnia symptoms such as difficulty falling asleep and shortened sleep time [61].

Studies conducted in persons with insomnia have also reported that high 24-h urinary cortisol levels were associated with increased total wake time in patients with chronic insomnia. For example, people with insomnia symptoms who slept less than 5 h had higher morning cortisol levels than those who slept more than 5 h [62]. It is also separately reported that elevated cortisol levels could increase the risk of suicide [63]. Future research is needed to demonstrate this possible mechanism.

This study’s findings should be interpreted with several limitations. First, the collection of data was performed through a self-report questionnaire, which may be vulnerable to recall bias. Second, the current study mainly captured the types and cumulative number of SLEs but paid less attention to the extent to which they affected participants. Future studies could explore whether the numbers and impact extent of SLEs have different effects on SI in person with MDD or not. Third, we mainly focused on the effect of negative stressful life events on SI and did not take positive life events into account. In addition, our study has a relatively small sample size, and the sample was drawn only from the Nanshan District of Shenzhen, thus lacking extrapolation and representation. The sample size could be expanded for further study.

5. Conclusions

Herein, our study illustrated that childhood physical abuse and the cumulative number of SLEs were longitudinally associated with SI in persons with MDD. Furthermore, insomnia symptoms played a longitudinal mediating role on the relationship between SLEs and SI. Prevention, screening, and early intervention strategies for insomnia symptoms in persons with MDD who experience SLEs may prevent SI, a more serious mental health outcome.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bs14060467/s1, Table S1: Baseline sample characteristics between eligible and ineligible participants; Table S2: The proportion (%) of SLEs in persons with MDD (n = 511); Figure S1: Mediating effects of insomnia symptoms on the relationship between different types of SLEs and SI.

Author Contributions

Writing—Original draft, Methodology, Visualization, Y.C. and X.H. (Xue Han); Software, Investigation, Y.J. (Yingchen Jiang), Y.J. (Yunbin Jiang), X.H. (Xinyu Huang); Data curation, R.X.; Project administration, Y.L. and H.Z.; Supervision, Writing—Reviewing and Editing, W.W., L.G., K.M.T., R.S.M., and B.F.; Supervision, Writing—Reviewing and Editing, Funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82373660 and 81761128030) and Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen Nanshan (Grant No. 11).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the institutional review board of Sun Yat-sen University School of Public Health (Ethical code: L2017044).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from Prof. Lu on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants of the study. The Depression Cohort in China (DCC) is conducted by the Sun Yat-sen University and Shenzhen Nanshan Center for Chronic Disease Control in Shenzhen, China.

Conflicts of Interest

Roger S. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Milken Institute; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, Abbvie, Atai Life Sciences. Dr. Roger S. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp. Kayla M. Teopiz has received fees from Braxia Scientific Corp. Other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Jin, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheung, T.; Balbuena, L.; Xiang, Y.-T. Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation and Planning in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Observation Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard-Devantoy, S.; Gorwood, P.; Annweiler, C.; Olié, J.-P.; Le Gall, D.; Beauchet, O. Suicidal Behaviours in Affective Disorders: A Defcit of Cognitive Inhibition? Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommersbach, T.J.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Rhee, T.G. Rising Rates of Suicidal Behaviors and Large Unmet Treatment Needs Among US Adults with a Major Depressive Episode, 2009 to 2020. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2023, 98, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Keyes, K.M. Major Depression with Co-Occurring Suicidal Thoughts, Plans, and Attempts: An Increasing Mental Health Crisis in US Adolescents, 2011–2020. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 327, 115352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.F.; Shamsul, A.S.; Maniam, T. Are Predictors of Future Suicide Attempts and the Transition from Suicidal Ideation to Suicide Attempts Shared or Distinct: A 12-Month Prospective Study among Patients with Depressive Disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Mu, F.; Liu, D.; Zhu, J.; Yue, S.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Predictors of Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempt and Suicide Death among People with Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 302, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Kirtley, O.J. The Integrated Motivational–Volitional Model of Suicidal Behaviour. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Nock, M.K. The Psychology of Suicidal Behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D. Stressful Life Events. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 6362–6364. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.; Kang, H.-J.; Kim, J.-W.; Kim, H.K.; Kang, H.-C.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-W.; Stewart, R.; Kim, J.-M. Associations of Serum Cortisol Levels, Stress Perception, and Stressful Events with Suicidal Behaviors in Patients with Depressive Disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Lai, X.; Zhao, C.; Tu, X.; Ding, N.; Ruan, S.; Jiang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, G. Longitudinal Relationships among Perceived Stress, Suicidal Ideation and Sleep Quality in Chinese Undergraduates: A Cross-Lagged Model. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 299, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sareen, J.; Afifi, T.O.; Bolton, S.-L.; Johnson, E.A.; Bolton, J.M. A Population-Based Longitudinal Study of Recent Stressful Life Events as Risk Factors for Suicidal Behavior in Major Depressive Disorder. Arch. Suicide Res. 2015, 19, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Q.; Liu, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z. Childhood Trauma and Suicidal Ideation among Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Effects of Character Strengths and Perceived Stress. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 30, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Pei, Y.; Dereje, S.B.; Chen, Q.; Yan, N.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. How Adverse and Benevolent Childhood Experiences Influence Depression and Suicidal Ideation in Chinese Undergraduates: A Latent Class Analysis. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2023, 28, 22–00242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.C.; Luo, D.; Wang, X.Q.; Zhu, J.; Wu, S.; Sun, T.; Li, X.Y.; Kang, L.; Ma, S.; Lu, B.; et al. Suicidal Ideation in College Students Having Major Depressive Disorder: Role of Childhood Trauma, Personality and Dysfunctional Attitudes. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 311, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, C.R.; Kleiman, E.M.; Kandlur, R.; Esposito, E.C.; Liu, R.T. Thwarted Belongingness Mediates Interpersonal Stress and Suicidal Thoughts: An Intensive Longitudinal Study with High-Risk Adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2022, 51, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelli, L.; Nearchou, F.A.; Vaiopoulos, C.; Stefanis, C.N.; Vitoratou, S.; Serretti, A.; Stefanis, N.C. Neuroticism, Social Network, Stressful Life Events: Association with Mood Disorders, Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation in a Community Sample of Women. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 226, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnon, S.; Brunstein Klomek, A.; Visoki, E.; Moore, T.M.; Argabright, S.T.; DiDomenico, G.E.; Benton, T.D.; Barzilay, R. Association of Cyberbullying Experiences and Perpetration With Suicidality in Early Adolescence. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2218746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Pentti, J.; Nordentoft, M.; Xu, T.; Rugulies, R.; Madsen, I.E.H.; Conway, P.M.; Westerlund, H.; Vahtera, J.; Ervasti, J.; et al. Association of Workplace Violence and Bullying with Later Suicide Risk: A Multicohort Study and Meta-Analysis of Published Data. Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e494–e503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tein, J.-Y. Life Events, Psychopathology, and Suicidal Behavior in Chinese Adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 86, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Raffeld, M.R.; Slopen, N.; Hale, L.; Dunn, E.C. Childhood Adversity and Insomnia in Adolescence. Sleep Med. 2016, 21, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, N.A.; Austin, A.E.; Wolfson, A.R.; Rojo-Wissar, D.M.; Munro, C.A.; Eaton, W.W.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Spira, A.P. The Association between Traumatic Life Events and Insomnia Symptoms among Men and Women: Results from the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-up Study. Sleep Health 2022, 8, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, T.M.; Walsh, P.G.; Ashrafioun, L.; Lavigne, J.E.; Pigeon, W.R. Sleep, Suicide Behaviors, and the Protective Role of Sleep Medicine. Sleep Med. 2020, 66, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M.; Jarrin, D.C. Epidemiology of Insomnia. Sleep Med. Clin. 2022, 17, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.-P.; Wang, X.-T.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Liu, X.; Jia, C.-X. Stressful Life Events, Insomnia and Suicidality in a Large Sample of Chinese Adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 249, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagini, L.; Miniati, M.; Marazziti, D.; Franceschini, C.; Zerbinati, L.; Grassi, L.; Sharma, V.; Riemann, D. Insomnia Symptoms Are Associated with Impaired Resilience in Bipolar Disorder: Potential Links with Early Life Stressors May Affect Mood Features and Suicidal Risk. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 299, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liao, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, W.; Teopiz, K.M.; Song, W.; Zhu, D.; Li, L.; et al. Association between Childhood Trauma and Medication Adherence among Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: The Moderating Role of Resilience. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, S.Ø.; Bulik, C.M.; Andreassen, O.A.; Rø, Ø.; Bang, L. Stressful Life Events among Individuals with a History of Eating Disorders: A Case-Control Comparison. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.N.; De Luca, V. The Effect of Lifetime Adversities on Resistance to Antipsychotic Treatment in Schizophrenia Patients. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 161, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Jin, X.; Jin, B.; Yang, Q. The Influence of Pre-Injury Stressful Life Events on the Life Quality and Mood Symptoms Following Cerebral Concussion. Chin. J. Behav. Med. Brain Sci. 2015, 24, 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Han, X.; Liao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Fan, B.; Zhang, H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Song, W.; Li, L.; Guo, L.; et al. Associations of Stressful Life Events with Subthreshold Depressive Symptoms and Major Depressive Disorder: The Moderating Role of Gender. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 325, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Kovacs, M.; Weissman, A. Assessment of Suicidal Intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1979, 47, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.S.F. Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric Properties with Chinese Community-dwelling Older People. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2350–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an Outcome Measure for Insomnia Research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and Standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the General Population. Med. Care 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tam, W.W.S.; Wong, P.T.K.; Lam, T.H.; Stewart, S.M. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for Measuring Depressive Symptoms among the General Population in Hong Kong. Compr. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, B.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for Screening to Detect Major Depression: Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2019, 365, l1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.Y.; Li, T.K.; Yu, N.X.; Pang, H.; Chan, B.H.Y.; Leung, G.M.; Stewart, S.M. Normative Data and Psychometric Properties of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) and the Abbreviated Version (CD-RISC2) among the General Population in Hong Kong. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Su, Y.; Lv, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, G.; Wei, J.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Q.; Tian, H.; Zhang, K.; et al. Childhood Adversity, Adulthood Adversity and Suicidal Ideation in Chinese Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: In Line with Stress Sensitization. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 272, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zisook, S.; Planeta, B.; Hicks, P.B.; Chen, P.; Davis, L.L.; Villarreal, G.; Sapra, M.; Johnson, G.R.; Mohamed, S. Childhood Adversity and Adulthood Major Depressive Disorder. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2022, 76, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yacaman-Mendez, D.; Hallgren, M.; Forsell, Y. Childhood Adversities, Negative Life Events and Outcomes of Non-Pharmacological Treatments for Depression in Primary Care: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 110, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanco-Roman, L.; Alvarez, K.; Corbeil, T.; Scorza, P.; Wall, M.; Gould, M.S.; Alegría, M.; Bird, H.; Canino, G.J.; Duarte, C.S. Association of Childhood Adversities With Suicide Ideation and Attempts in Puerto Rican Young Adults. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- av Kák Kollsker, S.; Coello, K.; Stanislaus, S.; Melbye, S.; Lie Kjærstad, H.; Stefanie Ormstrup Sletved, K.; Vedel Kessing, L.; Vinberg, M. Association between Lifetime and Recent Stressful Life Events and the Early Course and Psychopathology in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Bipolar Disorder, First-degree Unaffected Relatives and Healthy Controls: Cross-sectional Results from a Prospective Study. Bipolar Disord. 2022, 24, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.Y.; D’Arcy, C.; Li, M.; O’Donnell, K.J.; Caron, J.; Meaney, M.J.; Meng, X. Specific and Cumulative Lifetime Stressors in the Aetiology of Major Depression: A Longitudinal Community-Based Population Study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2022, 31, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.-Y.; Huang, Y.; Su, Y.-A.; Yu, X.; Lyu, X.-Z.; Liu, Q.; Si, T.-M. Association between Perceived Stressfulness of Stressful Life Events and the Suicidal Risk in Chinese Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Chin. Med. J. 2018, 131, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Su, Y.; Lv, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, G.; Wei, J.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Q.; Tian, H.; Zhang, K.; et al. Perceived Stressfulness Mediates the Effects of Subjective Social Support and Negative Coping Style on Suicide Risk in Chinese Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 265, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Murphy, M.L.M.; Prather, A.A. Ten Surprising Facts About Stressful Life Events and Disease Risk. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, N.G.; DiNitto, D.M.; Marti, C.N.; Segal, S.P. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Suicide Attempts among Those with Mental and Substance Use Disorders. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 69, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Chang, W.; Ran, H.; Fang, D.; Che, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Sun, H.; Lu, J.; Xiao, Y. Childhood Maltreatment and Suicidal Ideation in Chinese Children and Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Mindfulness. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, I.; Austin, J.L.; Gooding, P. Association of Childhood Maltreatment With Suicide Behaviors Among Young People. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2012563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, X.; Tang, B.; Fan, K.; Wen, N.; Zhao, K.; Xu, W.; Tang, W.; Chen, Y. Childhood Trauma and Insomnia Increase Suicidal Ideation in Schizophrenia Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 769743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, S.; Kapoor, S.; Lamis, D.A. Childhood Maltreatment, Impulsive Aggression, and Suicidality among Patients Diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder. Psychol. Trauma 2022, 14, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S.A.; Clark, C.; Smuk, M.; Power, C.; Davidson, T.; Rodgers, B. Childhood Adversity and Midlife Suicidal Ideation. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Tein, J.-Y.; Jia, C.-X. Life Stress, Insomnia, and Anxiety/Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 322, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Hu, Y.; Xia, L.; Wang, S.; Guo, C.; Shi, Y.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, K.; et al. Associations between Childhood Maltreatment and Suicidal Ideation in Depressed Adolescents: The Mediating Effect of Alexithymia and Insomnia. Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 135, 105990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagini, L.; Miniati, M.; Marazziti, D.; Sharma, V.; Riemann, D. Association among Early Life Stress, Mood Features, Hopelessness and Suicidal Risk in Bipolar Disorder: The Potential Contribution of Insomnia Symptoms. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 135, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Jia, C.-X. Life Stress and Suicidality Mediated by Insomnia and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. Sleep 2023, 3, zsad121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Gartland, N.; O’Connor, R.C. Stress, Cortisol and Suicide Risk. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2020, 152, 101–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.-Z.; Chen, J.-T.; Hu, Z.-Y.; Liu, G.-X.; Zhou, Y.-S.; Zhang, P.; Su, A.-X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Wei, R.-M.; et al. Effects of Sleep Reactivity on Sleep Macro-Structure, Orderliness, and Cortisol After Stress: A Preliminary Study in Healthy Young Adults. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2023, 15, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressle, R.J.; Feige, B.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Schmucker, C.; Benz, F.; Mey, N.C.; Riemann, D. HPA Axis Activity in Patients with Chronic Insomnia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case–Control Studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 62, 101588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardelli, I.; Serafini, G.; Cortese, N.; Fiaschè, F.; O’Connor, R.C.; Pompili, M. The Involvement of Hypothalamus–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) Axis in Suicide Risk. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).