Crafting a Job among Chinese Employees: The Role of Empowering Leadership and the Links to Work-Related Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Work Engagement and In-Role Performance

2.2. The Relationships between Empowering Leadership and Job Crafting

2.2.1. The Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Seeking Resources

2.2.2. The Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Seeking Challenges

2.2.3. The Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Reducing Demands

2.3. The Relationships among Job Crafting and Work Engagement and In-Role Performance

2.3.1. The Relationships among Seeking Resources and Work Engagement and In-Role Performance

2.3.2. The Relationships among Seeking Challenges and Work Engagement and In-Role Performance

2.3.3. The Relationships among Reducing Demands and Work Engagement and In-Role Performance

2.4. The Mediating Role of Employee Job-Crafting Behaviors

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Job Crafting

3.2.2. Empowering Leadership

3.2.3. Work Engagement

3.2.4. In-Role Performance

3.2.5. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Examining the Discriminability of Study Variables

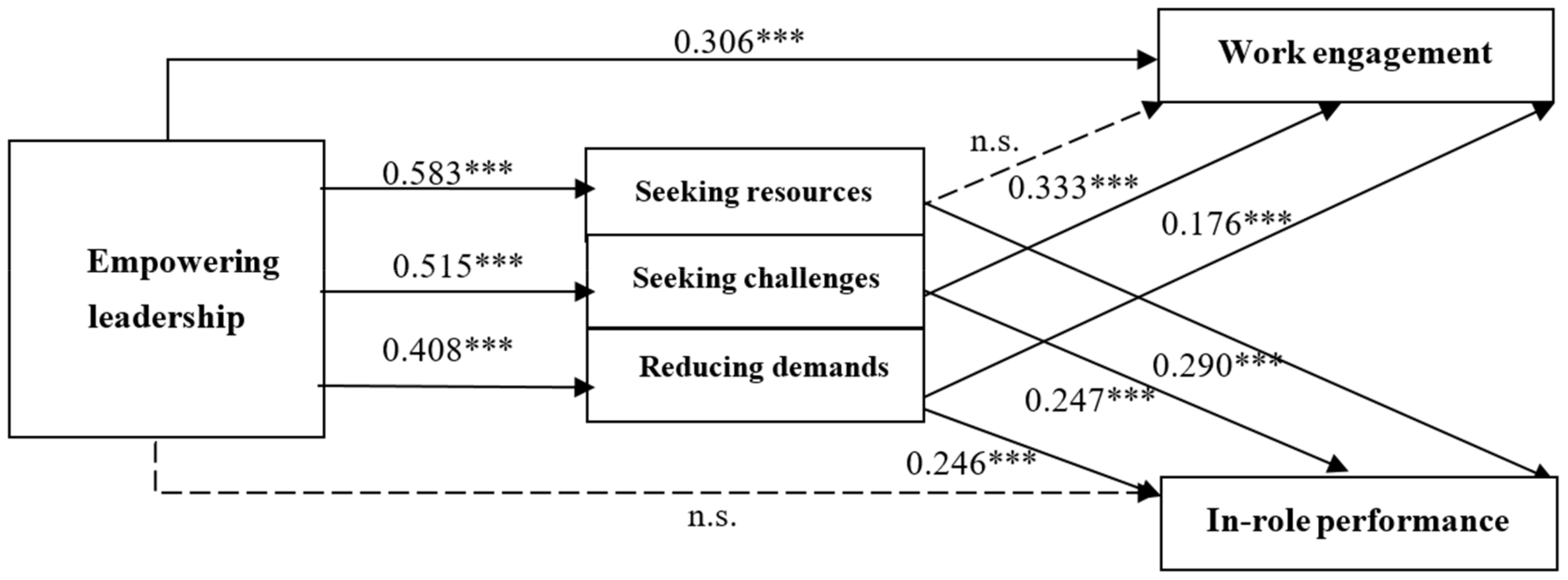

4.2. Examining the Direct Effect of Empowering Leadership on Work Engagement and In-Role Performance

4.3. Analysis of the Role of Job Crafting in the Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Work-Related Outcomes

5. Discussion

5.1. The Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Job Crafting

5.2. The Relationships between Job Crafting and Work Engagement and In-Role Performance

5.3. The Mediating Role of Job Crafting

5.4. Limitation and Future Research

5.5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Yang, H.; Weng, Q.; Zhu, L. How different forms of job crafting relate to job satisfaction: The role of person-job fit and age: Research and Reviews. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 11155–11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.F.; Parker, S.K. Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.C.; Zhang, B.R.; Shi, J.Q.; Yuan, M.S.; Ren, Y.W. Gain or Loss? Examining the double-edged sword effect of challenge demand on work-family enrichment. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2022, 54, 1234–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, S. Contextual antecedents of job crafting: Review and future research agenda. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2023, 47, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, M.; Francis, J.Y.; Shelley, D.D.; Seth, M.S.; Tsaib, C.Y. A review of the effectiveness of empowering leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A.; Prewett, M.S. Employee responses to empowering leadership: A meta-analysis. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audenaert, M.; Decramer, A. When empowering leadership fosters creative performance: The role of problem-solving demands and creative personality. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A. Can empowering leaders affect subordinates’ well-being and careers because they encourage subordinates’ job crafting behaviors? J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, G.; Lee, S.; Karau, S.J.; Dai, Y. The trickle-down effect of empowering leadership: A boundary condition of performance pressure. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzana, S.; Charoensukmongkol, P. Using approach-inhibition theory of power to explain how participative decision-making enhances innovative work behavior of high power distance-oriented employees. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2023, 10, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Yu, B. Antecedents and consequences of empowering leadership: Leader power distance, leader perception of team capability, and team innovation. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffeng, T.; Steenbergen, E.F.; Vries, F.; Steffens, N.K.; Ellemers, N. Reflective and decisive supervision: The role of participative leadership and team climate in joint decision-making. Regul. Gov. 2023, 17, 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.L.; Lim, R.A.; Santamaria, J.G.O. Business model innovation: A study of empowering leadership. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2021, 30, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cougot, B.; Gillet, N.; Moret, L.; Gauvin, J.; Caillet, P.; Fleury-Bahi, G.; Lesot, J.; Ollierou, F.; Armant, A.; Peltier, A.; et al. Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Stress in a French University Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study Combining the Measurement of Perceived Stress and Salivary Cortisol. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 8839893. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P. Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: The moderating role of organizational identification. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennerlein, T.; Kirkman, B.L. The Hidden Dark Side of Empowering Leadership: The Moderating Role of Hindrance Stressors in Explaining When Empowering Employees Can Promote Moral Disengagement and Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 107, 2220–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; LoBuglio, N.; Dutton, J.E.; Berg, J.M. Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job crafting in changing organizations: Antecedents and implications for exhaustion and performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chammas, C.B.; da Costa Hernandez, J.M. Development and validation of the general regulatory focus measure forced choice scale (GRFM-FC). Curr. Psychol. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, M.T.; Kulikowski, K. Toward an understanding of occupational burnout among employees with autism—The Job Demands-Resources theory perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 1582–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.B.; Li, R. A review of the literature of challenge and hindrance stressors. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2013, 35, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, K.; Sun, J.M.; Xu, G.Y. The effect of Job crafting on Job Engagement: Based on the Method of Relative Importance Analysis. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 8, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.G.; Shi, K.; Wang, Y.L.; Gong, H. Relationships between Challenge-hindrance Stressor, Employees’ work Engagement and Job Satisfaction. J. Manag. Sci. 2011, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, M.; Spain, S.; Yammarino, F.; Yun, S. Two faces of empowering leadership: Enabling and burdening. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Luo, Z. Formation Mechanism of the Negative Effects of Empowering Leadership: Based on the Theory of “Too-Much-of-a-Good-Thing”. J. Capit. Univ. Econ. Bus. 2017, 19, 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Qu, J. Analysis of Origins and Main Contents of Conservation of Resource Theory and Implications. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 2014, 15, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocal. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.Q. The Dimensionality and Measure of Empowering Leadership Behavior in the Chinese Organizations. Acta. Psychol. Sin. 2008, 40, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thun, S.; Bakker, A.B. Empowering leadership and job crafting: The role of employee optimism. Stress Health 2018, 34, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E. Design your own job through job crafting. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.T. Study on the Mechanism of Servant Leadership Inspires Employees’ Job Crafting. Soft. Sci. 2018, 32, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Harju, L.K.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hakanen, J.J. A multilevel study on servant leadership, job boredom and job crafting. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C. Transmission of reduction-oriented crafting among colleagues: A diary study on the moderating role of working conditions. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 91, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.H.; Shah, S.M.A.; Khalil, S.M. Servant Leadership, Job Crafting Behaviours, and Work Outcomes: Does Employee Conscientiousness Matters? J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Hambrick, D.C.; Sajons, G.B.; Quaquebeke, N.V. Leadership science beyond questionnaires. Leadersh. Q. 2023, 34, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dust, S.B.; Resick, C.J.; Mawritz, M.B. Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and the moderating role of mechanistic–Organic contexts. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Maguire, P.; Zhou, M.; Sun, H.; Wang, D. Exploring the influence of ethical leadership on voice behavior: How leader-member exchange, psychological safety and psychological empowerment influence employees’ willingness to speak out. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.; Ruiz, C.; Knorr, H. Employee Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Direct and Indirect Effect of Ethical Leadership. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2011, 28, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.; Martínez, R.; Bañón, A. Is unethical leadership a negative for Employees’ personal growth and intention to stay? The buffering role of responsibility climate. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2021, 18, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Gao, Y.Q. Ethical leadership and work engagement: The roles of psychological empowerment and power distance orientation. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1991–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.61 | 0.50 | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Age | 3.56 | 1.52 | 0.07 | — | |||||||||

| 3. Education | 2.50 | 0.99 | −0.14 ** | −0.30 ** | — | ||||||||

| 4. Tenure | 2.63 | 1.42 | 0.03 | 0.65 ** | −0.13 ** | — | |||||||

| 5. Position | 1.50 | 0.81 | −0.19 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.01 | 0.29 ** | — | ||||||

| 6. Empowering leadership | 3.98 | 0.70 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.14 ** | 0.02 | 0.12 ** | — | |||||

| 7. Seeking resources | 4.36 | 0.50 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.11 ** | 0.55 ** | — | ||||

| 8. Seeking challenges | 3.86 | 0.68 | −0.11 ** | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.20 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.47 ** | — | |||

| 9. Reducing demands | 3.87 | 0.68 | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.13 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.46 ** | — | ||

| 10. Work engagement | 3.88 | 0.74 | −0.02 | 0.11 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.08 * | 0.19 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.45 ** | — | |

| 11. In-role performance | 4.26 | 0.55 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.08 * | 0.19 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.53 ** | — |

| Model | /df | CFI | TLI | AIC | BIC | SRMR | RMSEA (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six factors | 3.122 | 0.950 | 0.941 | 32,021.574 | 32,421.525 | 0.042 | 0.043 (0.038, 0.047) |

| Five factors | 6.397 | 0.854 | 0.833 | 32,819.779 | 33,196.745 | 0.058 | 0.072 (0.068, 0.076) |

| Four factors | 5.145 | 0.891 | 0.877 | 32,529.365 | 32,887.942 | 0.057 | 0.062 (0.058, 0.066) |

| Three factors | 8.240 | 0.798 | 0.776 | 33,309.611 | 33,654.397 | 0.068 | 0.083 (0.079, 0.088) |

| Two factors (a) | 8.304 | 0.709 | 0.680 | 34,073.749 | 34,409.340 | 0.087 | 0.100 (0.096, 0.104) |

| Two factors (b) | 10.639 | 0.730 | 0.703 | 33,924.200 | 34,259.792 | 0.080 | 0.096 (0.092, 0.100) |

| Single factor | 13.826 | 0.640 | 0.606 | 34,735.878 | 35,066.873 | 0.088 | 0.111 (0.107, 0.115) |

| Model | /df | CFI | TLI | AIC | BIC | Adjusted BIC | SRMR | RMSEA (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized model | 4.452 | 0.942 | 0.901 | 12,964.353 | 13,313.736 | 13,072.411 | 0.056 | 0.069 [0.061, 0.076] |

| Rival model 1 (The final model) | 4.404 | 0.942 | 0.903 | 12,963.447 | 13,308.233 | 13,070.083 | 0.056 | 0.069 [0.061, 0.076] |

| Rival model 2 | 5.002 | 0.931 | 0.885 | 13,015.288 | 13,360.074 | 13,121.924 | 0.068 | 0.074 [0.067, 0.081] |

| Rival model 3 | 4.929 | 0.932 | 0.888 | 13,013.950 | 13,354.139 | 13,119.164 | 0.067 | 0.073 [0.066, 0.081] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Huang, X. Crafting a Job among Chinese Employees: The Role of Empowering Leadership and the Links to Work-Related Outcomes. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060451

Chen M, Zhang Y, Xu H, Huang X. Crafting a Job among Chinese Employees: The Role of Empowering Leadership and the Links to Work-Related Outcomes. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):451. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060451

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Mengyan, Yonghong Zhang, Haoyang Xu, and Xiting Huang. 2024. "Crafting a Job among Chinese Employees: The Role of Empowering Leadership and the Links to Work-Related Outcomes" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060451

APA StyleChen, M., Zhang, Y., Xu, H., & Huang, X. (2024). Crafting a Job among Chinese Employees: The Role of Empowering Leadership and the Links to Work-Related Outcomes. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060451