Advice Network Centrality as a Social Origin of Task Crafting: The Bridging Roles of Basic Psychological Needs

Abstract

1. Introduction

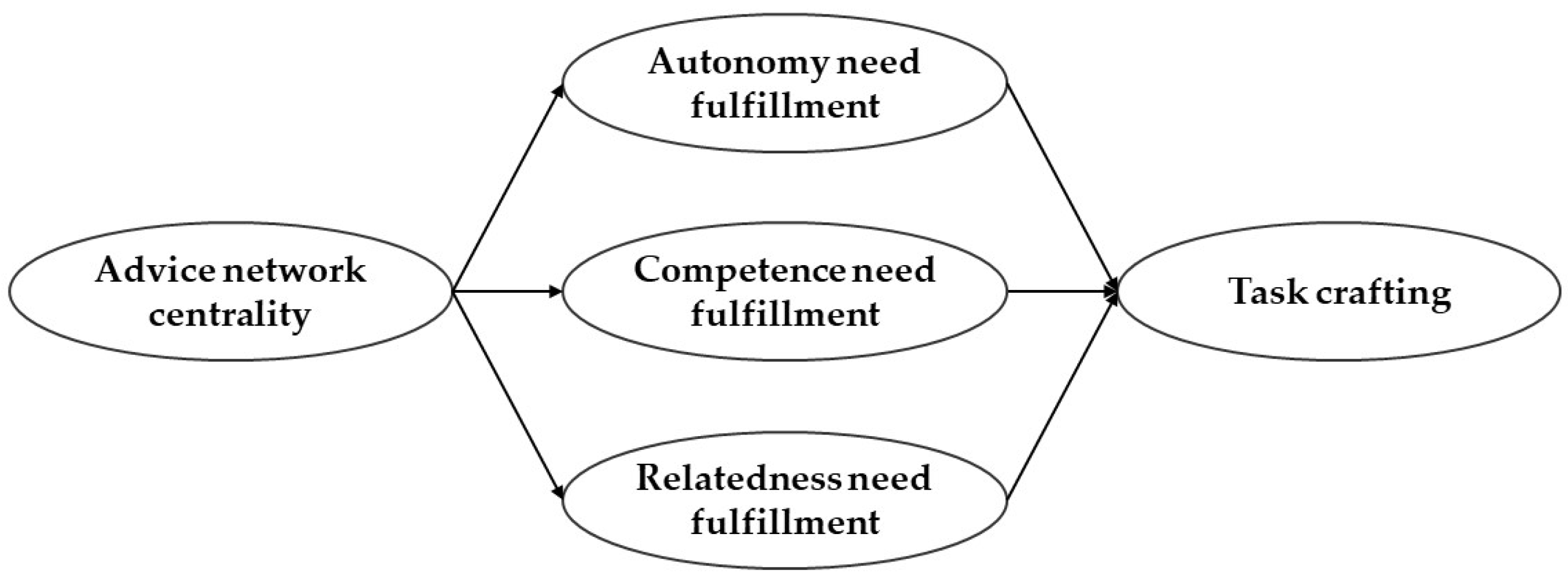

2. Theoretical Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Advice Networks and Need Fulfillment

2.2. Need Fulfillment and Task Crafting

2.3. Advice Networks, Need Fulfillment, and Task Crafting

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Advice Network Centrality

3.2.2. Basic Psychological Needs

3.2.3. Task Crafting

3.2.4. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Testing

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Overall Findings

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Gevers, J.M. Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Miwa, T.; Morikawa, T. Preferences and expectations of Japanese employees toward telecommuting frequency in the post-pandemic era. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Hackman, J.R. Not what it was and not what it will be: The future of job design research. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. Design your own job through job crafting. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C.; Appelbaum, E.; Shevchuk, I. Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Law, K.S.; Zhou, J. Why is underemployment related to creativity and OCB? A task-crafting explanation of the curvilinear moderated relations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Hur, W.M.; Kang, S. How and when are job crafters engaged at work? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Baek, S.I.; Shin, Y. The effect of the congruence between job characteristics and personality on job crafting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Im, J.; Qu, H. Exploring antecedents and consequences of job crafting. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Shin, Y.; Baek, S.I. The impact of job demands and resources on job crafting. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2017, 33, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, D.J.; Galaskiewicz, J.; Greve, H.R.; Tsai, W. Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilduff, M.; Brass, D.J. Organizational social network research: Core ideas and key debates. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 317–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Application; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, D.E. Friendship and advice networks in the context of professional values. Adm. Sci. Q. 2004, 49, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, H. Network centrality, power, and innovation involvement: Determinants of technical and administrative roles. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 471–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrowe, R.T.; Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Kraimer, M.L. Social networks and the performance of individuals and groups. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangialosi, N.; Odoardi, C.; Battistelli, A.; Baldaccini, A. The social side of innovation: When and why advice network centrality promotes innovative work behaviours. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2021, 30, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Ferris, D.L.; Chang, C.H.; Rosen, C.C. A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1195–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; De Witte, H.; Soenens, B.; Lens, W. Capturing autonomy, competence, and relatedness at work: Construction and initial validation of the Work-related Basic Need Satisfaction scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 2013, 23, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovjanic, S.; Schuh, S.C.; Jonas, K.; Quaquebeke, N.V.; Van Dick, R. How do transformational leaders foster positive employee outcomes? A self-determination-based analysis of employees’ needs as mediating links. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1031–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1979, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, M.E.; Brass, D.J. Changing patterns or patterns of change: The effects of a change in technology on social network structure and power. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, D.J. A social network perspective on organizational psychology. In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Psychology; Kozlowski, S.W.J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 667–695. [Google Scholar]

- Brass, D.J.; Burkardt, M.E. Centrality and power in organizations. In Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form, and Action; Nohria, N., Eccles, R.G., Eds.; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bono, J.E.; Anderson, M.H. The advice and influence networks of transformational leaders. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, H.; Andrews, S.B. Power, social influence, and sense making: Effects of network centrality and proximity on employee perceptions. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagenczyk, T.J.; Murrell, A.J. It is better to receive than to give: Advice network effects on job and work-unit attachment. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Karaeminogullari, A.; Bauer, T.N.; Ellis, A.M. Perceived overqualification at work: Implications for extra-role behaviors and advice network centrality. J. Manage. 2020, 46, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Yu, M. Interactive effect of leader–member tie and network centrality on leadership effectiveness. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2017, 45, 1197–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O.; Van Yperen, N.W. Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manage. J. 2004, 47, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, T.T.; Bedell, M.D.; Johnson, J.L. The social fabric of a team-based MBA program: Network effects on student satisfaction and performance. Acad. Manage. J. 1997, 40, 1369–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.; Landis, B.; Zhang, Z.; Anderson, M.H.; Shaw, J.D.; Kilduff, M. Integrating personality and social networks: A meta-analysis of personality, network position, and work outcomes in organizations. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 1243–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W. Newcomers’ relationships: The role of social network ties during socialization. Acad. Manage. J. 2002, 45, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, R.Y.J.; Ingram, P.; Morris, M.W. From the head and the heart: Locating cognition-and affect-based trust in managers’ professional networks. Acad. Manage. J. 2008, 51, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Billings, R.S. The effect of self-efficacy and issue characteristics on threat and opportunity categorization. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 1253–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.A.; Buckley, F. Exploring the impact of trust on research scientists’ work engagement: Evidence from Irish science research centres. Pers. Rev. 2013, 42, 396–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Daniels, D. Motivation. In Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Borman, W.C., Ilgen, D.R., Klimoski, R.J., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 225–254. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W.; Song, Y. Promoting employee job crafting at work: The roles of motivation and team context. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Jung, H. Differential roles of self-determined motivations in describing job crafting behavior and organizational change commitment. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3376–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, P.V. Network data and measurement. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1990, 16, 435–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K.J.; Lim, B.C.; Saltz, J.L.; Mayer, D.M. How do they get there? An examination of the antecedents of centrality in team networks. Acad. Manage. J. 2004, 47, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook; Sage: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Johnson, J.C. Analyzing Social Networks; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Slemp, G.R.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. The Job Crafting Questionnaire: A new scale to measure the extent to which employees engage in job crafting. Int. J. Wellbeing 2013, 3, 126–146. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, I.; Kim, M. Proactive personality as a critical condition for seeking advice and crafting tasks in ambiguous roles. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnellan, M.B.; Oswald, F.L.; Baird, B.M.; Lucas, R.E. The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychol. Assess. 2006, 18, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary-Kelly, S.W.; Vokurka, R.J. The empirical assessment of construct validity. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J.M.; Grant, A.M.; Johnson, V. When callings are calling: Crafting work and leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 973–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 54, 299–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciaro, T.; Barsade, S.G.; Edmondson, A.C.; Gibson, C.B.; Krackhardt, D.; Labianca, G. The integration of psychological and network perspectives in organizational scholarship. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 1162–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I. You reap what you sow: How proactive individuals are selected as preferred work partners. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 25985–25995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pimenta, R.; de Freitas, C.P.P.; Wechsler, S.M. Basic psychological need satisfaction, job crafting, and meaningful work: Network analysis. Trends Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, S. Crafting task and cognitive job boundaries to enhance self-determination, impact, meaning and competence at work. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Industry | 0.64 | 0.48 | |||||||||

| 2. Organization size | 33.53 | 10.45 | −0.44 * | ||||||||

| 3. Gender | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.15 * | 0.04 | |||||||

| 4. Organizational tenure | 5.42 | 6.42 | 0.12 | 0.23 ** | 0.02 | ||||||

| 5. Openness to experience | 3.31 | 0.53 | 0.20 ** | −0.16 * | 0.16 * | 0.02 | |||||

| 6. Advice network centrality | 14.01 | 13.18 | 0.35 ** | −0.32 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.15 * | 0.22 ** | ||||

| 7. Autonomy need fulfillment | 3.19 | 0.69 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.23 ** | 0.09 | 0.25 ** | 0.25 ** | |||

| 8. Competence need fulfillment | 3.48 | 0.68 | 0.18 ** | 0.02 | 0.24 ** | 0.14 * | 0.39 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.44 ** | ||

| 9. Relatedness need fulfillment | 3.75 | 0.68 | 0.20 ** | −0.03 | 0.17 * | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.17 * | 0.21 ** | 0.39 ** | |

| 10. Task crafting | 3.32 | 0.68 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.29 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.19 ** |

| Variables | Autonomy Need Fulfillment | Competence Need Fulfillment | Relatedness Need Fulfillment | Task Crafting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Industry | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.16 | −0.10 |

| Organization size | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.08 | −0.05 |

| Gender | 0.14 * | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Organizational tenure | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.15 ** |

| Openness to experience | 0.21 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.07 | 0.22 ** |

| Advice network centrality | 0.22 ** | 0.15 * | 0.10 | 0.13 * |

| Autonomy need fulfillment | 0.34 ** | |||

| Competence need fulfillment | 0.24 ** | |||

| Relatedness need fulfillment | −0.04 | |||

| R2 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.50 |

| F | 5.63 ** | 9.59 ** | 2.65 * | 20.72 ** |

| Mediators | Effect (b) | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effect | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.009 |

| Need for autonomy | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.007 |

| Need for competence | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.004 |

| Need for relatedness | −0.000 | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, I. Advice Network Centrality as a Social Origin of Task Crafting: The Bridging Roles of Basic Psychological Needs. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060440

Shin I. Advice Network Centrality as a Social Origin of Task Crafting: The Bridging Roles of Basic Psychological Needs. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):440. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060440

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Inyong. 2024. "Advice Network Centrality as a Social Origin of Task Crafting: The Bridging Roles of Basic Psychological Needs" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060440

APA StyleShin, I. (2024). Advice Network Centrality as a Social Origin of Task Crafting: The Bridging Roles of Basic Psychological Needs. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060440