The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Workplace Safety: The Significance of Employees’ Moral Identity

Abstract

1. Introduction

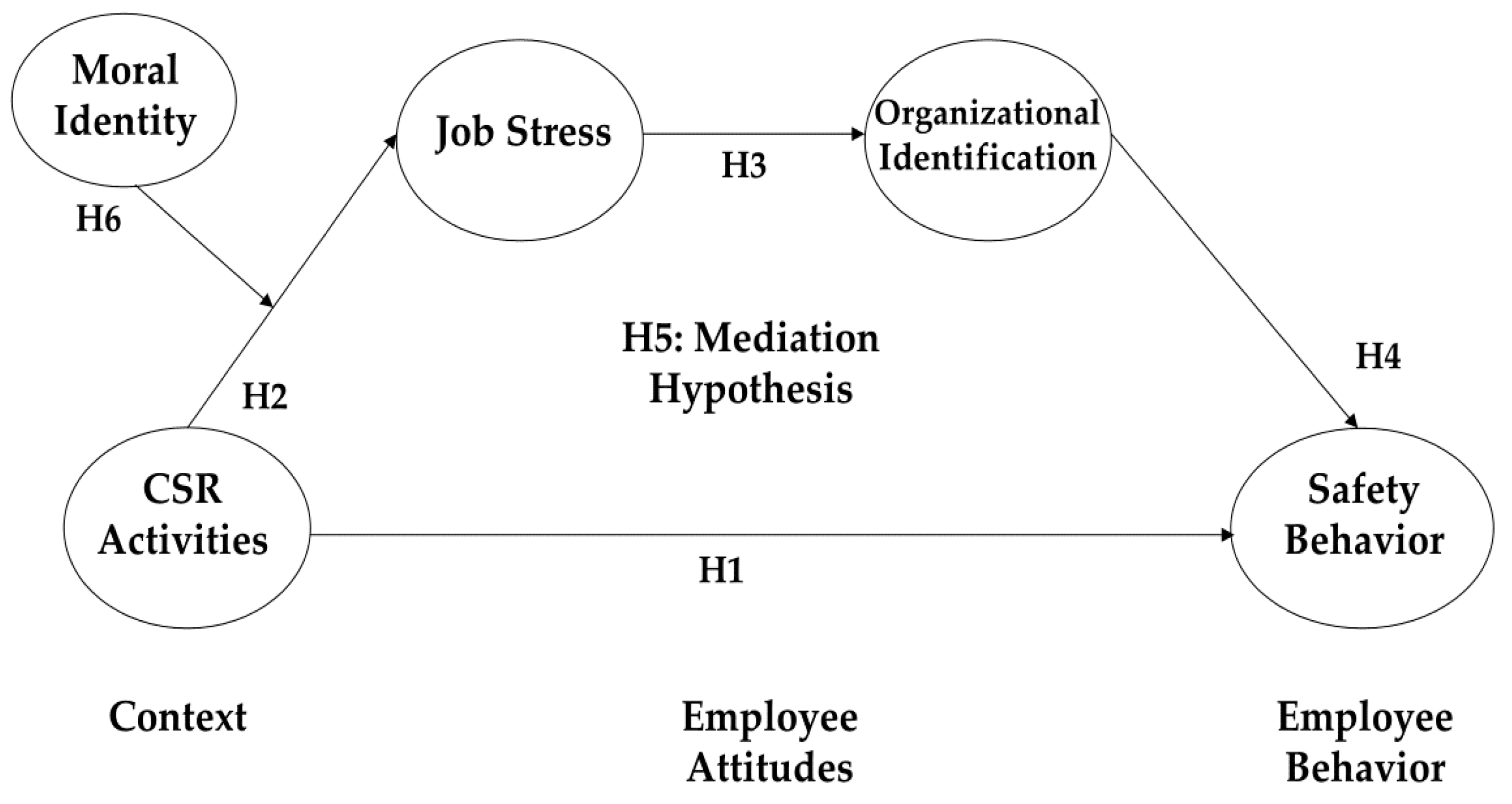

- To examine the direct relationship between CSR and employee safety behavior;

- To investigate the sequential mediating effects of job stress and organizational identification on the relationship between CSR and employee safety behavior;

- To explore the moderating role of moral identity on the relationship between CSR and job stress.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility and Safety Behavior

2.2. CSR and Job Stress

2.3. Job Stress and Organizational Identification

2.4. Organizational Identification and Safety Behavior

2.5. Sequential Mediation of Job Stress and Organizational Identification in the Corporate Social Responsibility–Safety Behavior Link

2.6. Moderation of Moral Identity in the Corporate Social Responsibility–Job Stress Link

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. CSR (Time Point 1, Gathered from Employees)

3.2.2. Moral Identity (Time Point 1, Gathered from Employees)

3.2.3. Job Stress (Time Point 2, Gathered from Employees)

3.2.4. Organizational Identification (Time Point 2, Gathered from Employees)

3.2.5. Safety Behavior (Time Point 3, Gathered from Employees)

3.2.6. Control Variables

3.3. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

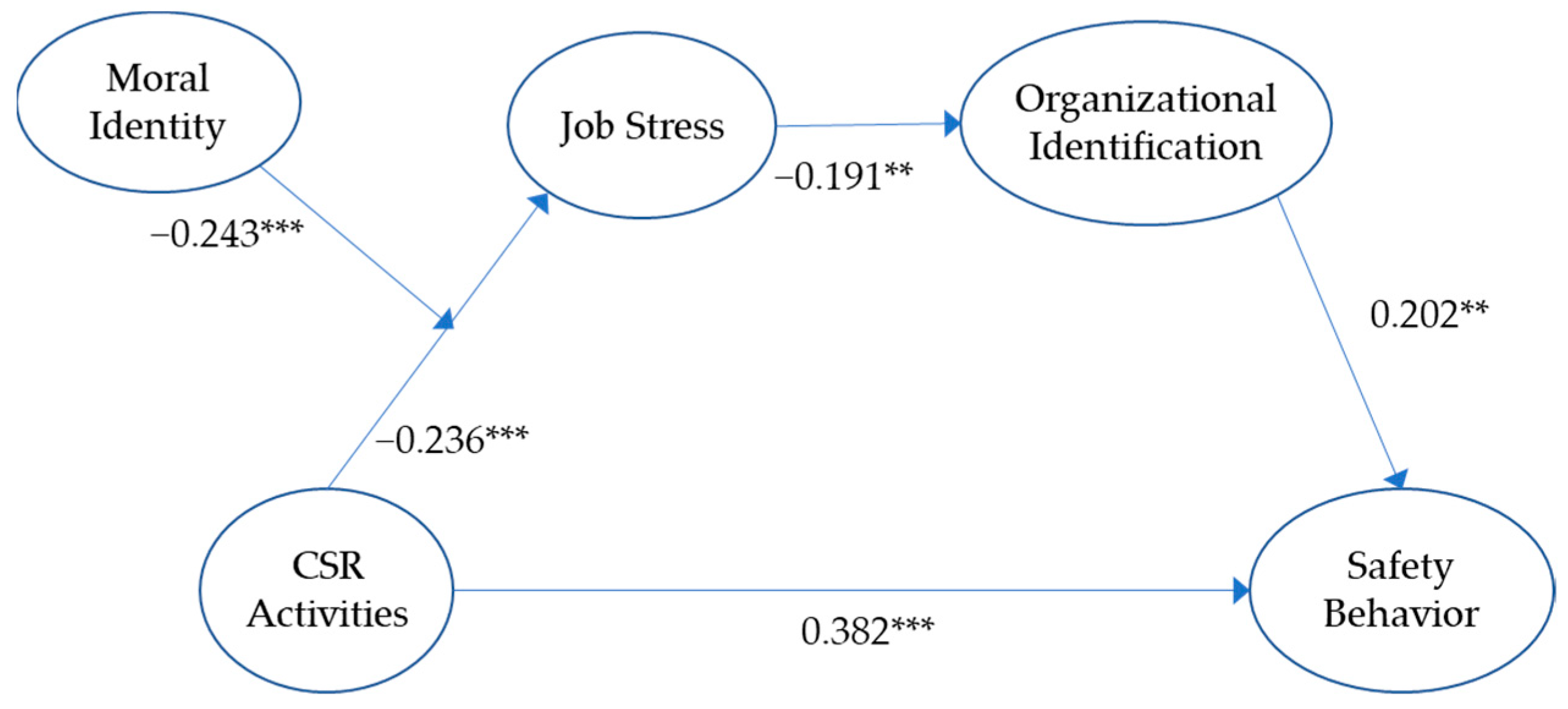

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Results of Mediation Analysis

4.5. Analysis Results of Sequential Mediation

4.6. Results of Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Ma, X.; Pomare, C.; Zhang, Y. When doing good for society is good for shareholders: Importance of alignment between strategy and CSR performance. Rev. Account. Stud. 2022, 28, 1074–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.H. Corporate social responsibility in small- and medium-sized fast-growth private firms: How it is conceived, enacted, and communicated. In The Routledge Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility Communication; Chapter 18; O’Connor, A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility & financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603–609. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, T.; Berman, S. A brand new brand of corporate social performance. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Elbanna, S. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) implementation: A review and a research agenda towards an integrative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 183, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Meta-analyses on corporate social responsibility (CSR)—A literature review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2022, 72, 627–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multi-level theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J. The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1518–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Chiu, C.J.; Yang, C.F.; Pai, D.C. The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.V.; Garcia, A.; Rodriguez, L. Sustainable development and corporate performance: A study based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.W.; Yang, M.L. The effect of corporate social performance on financial performance: The moderating effect of ownership concentration. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V. Consistency matters! How and when does corporate social responsibility affect employees’ organizational identification? J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1141–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: An integrative review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.-T.; Kim, N.-M. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, K.; Hattrup, K.; Spiess, S.O.; Lin-Hi, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J. The influence of corporate social responsibility on employee safety behavior: The mediating effect of psychological safety and the moderating role of authentic leadership. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1090404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.J.; Sarpy, S.A.; Tesluk, P.E.; Smith-Crowe, K. General safety performance: A test of a grounded theoretical model. Pers. Psychol. 2002, 55, 429–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Bradley, J.C.; Wallace, J.C.; Burke, M.J. Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, C.; Wang, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Responding to a major global crisis: The effects of hotel safety leadership on employee safety behavior during COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3365–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Cotterell, N.; Marvel, J. Reciprocation ideology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitener, E.M.; Brodt, S.E.; Korsgaard, M.A.; Werner, J.M. Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns, K.J.; Reader, T. Organizational support and safety outcomes: An uninvestigated relationship? Saf. Sci. 2008, 6, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, B.E.; Shanock, L.R.; Miller, L.R. Advancing organizational support theory into the twenty-first century world of work. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Morgeson, F.P.; Gerras, S.J. Climate as a moderator of the relationship between leader-member exchange and content specific citizenship: Safety climate as an exemplar. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Roeck, K.; Maon, F. Building the theoretical puzzle of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Shirom, A.; Golembiewski, R. Conservation of resources theory. In Handbook of Organizational Behavior; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1723–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, B.J. Analysis of the importance of job insecurity, psychological safety and job satisfaction in the CSR-performance link. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Luo, J. Corporate social responsibility as an employee governance tool: Evidence from a quasi-experiment. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoteleb, S.A. A new look at the relationship between job stress and organizational commitment: A three-wave longitudinal study. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.R.; Peccei, R. Perceived organizational support, organizational identification, and employee outcomes. J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M. Relationship of job stress and Type-A behavior to employees’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment, psychosomatic health problems, and turnover motivation. Hum. Relat. 1990, 43, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluss, D.M.; Ashforth, B.E. Relational Identity and Identification: Defining Ourselves Through Work Relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourigny, L.; Baba, V.V.; Han, J.; Wang, X. Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. The causal relation between job attitudes and performance: A meta-analysis of panel studies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole Publishing: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers, N.; Spears, R.; Doosje, B. Self and social identity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avanzi, L.; van Dick, R.; Fraccaroli, F.; Sarchielli, G. The downside of organizational identification: Relations between identification, workaholism and well-being. Work Stress 2014, 28, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Martin, L.; Tyler, T. Process-orientation versus outcome-orientation during organizational change: The role of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, J.K.; Yorio, P.L. A system of safety management practices and worker engagement for reducing and preventing accidents: An empirical and theoretical investigation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 68, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Schwarz, G.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulki, J.P.; Jaramillo, J.F.; Locander, W.B. Effect of ethical climate on turnover intention: Linking attitudinal and stress theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 78, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcelik, H.; Langton, N.; Aldrich, H. Doing well and doing good: The relationship between leadership practices that facilitate a positive emotional climate and organizational performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Cable, D.M. The value of value congruence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liedtka, J.M. Value congruence: The interplay of individual and organizational value systems. J. Bus. Ethics 1989, 8, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Bynum, B.H.; Piccolo, R.F.; Sutton, A.W. Person-organization value congruence: How transformational leaders influence work group effectiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Choi, S.Y. Does a good company reduce the unhealthy behavior of its members?: The mediating effect of organizational identification and the moderating effect of moral identity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, K.; Reed, A., II. The self-importance of moral identity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Thornton, M.A.; Skarlicki, D.P. Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 895–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, E.J.; Sung, M. Corporate social responsibility in Korea: How to communicate with local stakeholders. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 634–647. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, S. Powerless in the middle: Why Korean workers are disengaged from corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Asian Public Policy 2019, 12, 316–331. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.H.; Jung, S.Y. The influence of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: The sequential mediating effect of meaningfulness of work and perceived organizational support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma, A. The robustness of LISREL against small sample sizes in factor analysis models. In Systems under Indirect Observation: Causality, Structure, Prediction (Part I); Jöreskog, K.G., Wold, H., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- De Roeck, K.; Marique, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Swaen, V. Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: Mediating roles of overall justice and organisational identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Testing Mediational Models with Longitudinal Data: Questions and Tips in the Use of Structural Equation Modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; Aquino, K.; Freeman, D. Beyond moral reasoning: A review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics. Bus. Ethics Q. 2008, 18, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; van Jaarsveld, D.D.; Walker, D.D. Getting even for customer mistreatment: The role of moral identity in the relationship between customer interpersonal injustice and employee sabotage. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Freeman, D.; Reed, A.; Lim, V.K.G.; Felps, W. Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.; Aquino, K.; Levy, E. Moral identity and judgments of charitable behaviors. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJoy, D.M.; Wilson, M.G.; Vandenberg, R.J.; McGrath-Higgins, A.L.; Griffin-Blake, C.S. Assessing the impact of healthy work organization intervention. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motowidlo, S.J.; Packard, J.S.; Manning, M.R. Occupational stress: Its causes and consequences for job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.; Baba, V.V. Job stress and burnout among Canadian managers and nurses: An empirical examination. Can. J. Public Health 2000, 91, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.S.; Sinclair, R.R.; Thomas, J.L. The multilevel effects of occupational stressors on soldiers’ well-being, organizational attachment, and readiness. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 276–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jex, S.M. Stress and Job Performance: Theory, Research, and Implications for Managerial Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- van Dick, R.; Wagner, U.; Stellmacher, J.; Christ, O. The utility of a broader conceptualization of organizational identification: Which aspects really matter? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inness, M.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Stride, C.B. Transformational leadership and employee safety performance: A within-person, between-jobs design. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A. Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Conditional process modeling: Using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes. In Quantitative Methods in Education and the Behavioral Sciences: Issues, Research, and Teaching. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course; Hancock, G.R., Mueller, R.O., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 219–266. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brace, N.; Kemp, R.; Snelgar, R. SPSS for Psychologists: A Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows, 2nd ed.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agan, Y.; Kuzey, C.; Acar, M.F.; Açıkgöz, A. The relationships between corporate social responsibility, environmental supplier development, and firm performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1872–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Piderit, S.K. How does doing good matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on employees. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2009, 36, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, H. Socially responsible human resource management and employee support for external CSR: Roles of organizational CSR climate and perceived CSR directed toward employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Delobbe, N. Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Moore, J.H.; Wang, Z. Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: A moderated mediation model of organizational identification and moral identity. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; He, W. Corporate social responsibility and employee organizational citizenship behavior: The pivotal roles of ethical leadership and organizational justice. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.Y. The influence of cultural values on perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Application of Hofstede’s dimensions to Korean public relations practitioners. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Miao, Q.; Hofman, P.S.; Zhu, C.J. The impact of socially responsible human resource management on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of organizational identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynhardt, T.; Brieger, S.A.; Hermann, C. Organizational public value and employee life satisfaction: The mediating roles of work engagement and organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 31, 1560–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.S.; Shin, Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.; Sung, S.Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. Top management ethical leadership and firm performance: Mediating role of ethical and procedural justice climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.L.; Hackett, R.D.; Liang, J. Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support-employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.49 | 0.50 | - | |||||||

| 2. Education | 2.75 | 0.79 | −0.19 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. Tenure | 7.83 | 7.68 | −0.31 ** | −0.07 | - | |||||

| 4. Position | 2.97 | 1.62 | −0.46 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.27 ** | - | ||||

| 5. CSR | 3.15 | 0.71 | −0.21 ** | 0.05 | 0.19 ** | 0.14 * | - | |||

| 6. MI | 3.74 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.14 * | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.17 * | - | ||

| 7. JS | 2.90 | 0.78 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.25 ** | −0.13 * | - | |

| 8. OI | 3.41 | 0.73 | −0.22 ** | −0.02 | 0.17 * | 0.20 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.29 ** | −0.18 ** | - |

| 9. SB | 3.68 | 0.66 | −0.19 ** | 0.03 | 0.14 * | 0.10 | 0.46 ** | 0.26 ** | −0.07 | 0.37 ** |

| Hypothesis | Path | Unstandardized Estimate | S.E. | Standardized Estimate | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CSR → Safety Behavior | 0.305 | 0.060 | 0.382 *** | Yes |

| 2 | CSR → Job Stress | −0.223 | 0.066 | −0.236 *** | Yes |

| 3 | Job Stress → Organizational Identification | −0.155 | 0.057 | −0.191 ** | Yes |

| 4 | Organizational Identification → Safety Behavior | 0.210 | 0.069 | 0.202 ** | Yes |

| 6 | CSR × Moral Identity | −0.382 | 0.102 | −0.243 *** | Yes |

| Model (Hypothesis 5) | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSR → Job Stress → Organizational Identification → Safety Behavior | 0.305 | 0.007 | 0.312 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, Y.; Roh, T. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Workplace Safety: The Significance of Employees’ Moral Identity. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060429

Hong Y, Roh T. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Workplace Safety: The Significance of Employees’ Moral Identity. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(6):429. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060429

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Yunsook, and Taewoo Roh. 2024. "The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Workplace Safety: The Significance of Employees’ Moral Identity" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 6: 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060429

APA StyleHong, Y., & Roh, T. (2024). The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Workplace Safety: The Significance of Employees’ Moral Identity. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060429