Savoring Belief, Resilience, and Meaning in Life as Pathways to Happiness: A Sequential Mediation Analysis among Taiwanese University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation and Research Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Relationship between Savoring Belief and Happiness

2.2. The Mediating Role of Resilience in the Relationship between Savoring Belief and Happiness

2.3. The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life in the Relationship between Savoring Belief and Happiness

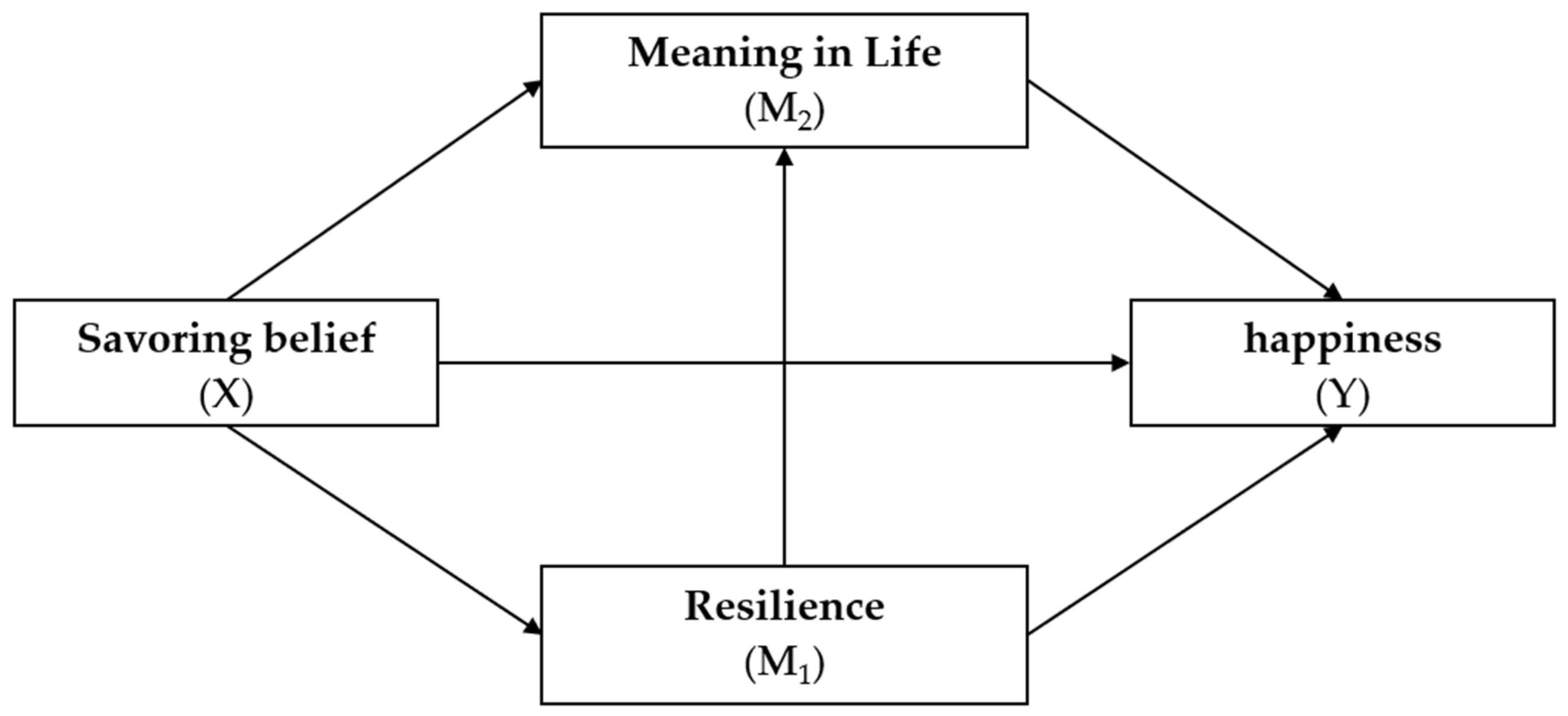

2.4. The Overall Relationship among Savoring Belief, Resilience, Meaning in Life, and Happiness

2.5. The Present Research

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Savoring Belief Inventory (SBI)

3.2.2. Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS)

3.2.3. Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)

3.2.4. Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ)

3.3. Statistical Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.2. Test the Extent of the Common Method Variance (CMV)

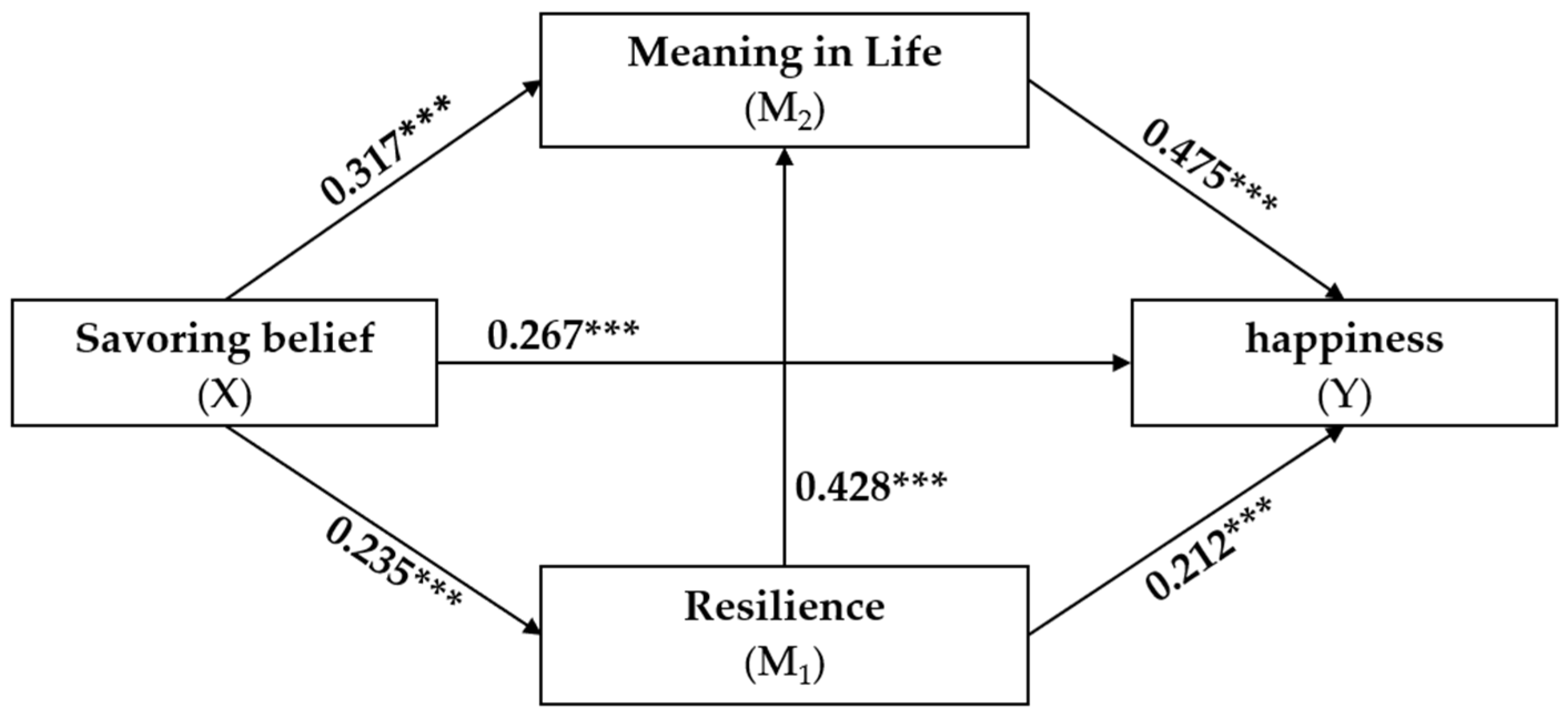

4.3. Testing the Sequential Mediation Model and Validating the Research Hypotheses

4.4. Comparison of Differences in Gender, Grade, and Major on the Measures

5. Discussion

5.1. Investigating the Positive Correlation between Savoring Belief and Happiness

5.2. Exploring the Mediating Role of Resilience in the Relationship between Savoring Belief and Happiness

5.3. Examining the Mediating Role of Meaning in Life in the Savoring Belief-Happiness Nexus

5.4. Assessing the Sequential Mediation of Resilience and Meaning in Life in the Context of Savoring Belief and Happiness

5.5. Analyzing the Impact of Savoring Belief on Happiness: Differences in Gender, Grade, and Major

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Educational Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research Scopes

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, Particularly Regarding Education; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Low, X.Q.; Chong, S.L. Helicopter Parenting and Resilience Among Malaysian Chinese University Students: The Mediating Role of Fear of Negative Evaluation. J. Adult Dev. 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, J.C. Level and inequality of happiness in nations: Does greater happiness of a greater number imply greater inequality in happiness? J. Happiness Stud. 2005, 6, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzarano, F.B.; Yazdani, N.; Zucchetto, J.M.; Siedlecki, K.L. Does Neurocognition Predict Subjective Well-Being? J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 3713–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intelisano, S.; Krasko, J.; Luhmann, M. Integrating philosophical and psychological accounts of happiness and well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 161–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagran, M.A.; Martin, L. Academic librarians: Their understanding and use of emotional intelligence and happiness. J. Acad. Libr. 2022, 48, 102466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M.; Magyar-Moe, J.L. The measurement and utility of adult subjective well-being. In Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures; Lopez, S.J., Snyder, C.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, F.B.; Veroff, J. Savoring: A New Model of Positive Experience; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R. APA’s resilience initiative. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2005, 36, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.-A.; Jung, Y.-E.; Kim, D.-J.; Yim, H.-W.; Kim, J.-J.; Kim, T.-S.; Lee, C.-U.; Lee, C.; Chae, J.-H. Characteristics associated with low resilience in patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, S.A. Psychological vulnerability, resilience, and subjective well-being: The mediating role of hope. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, R.; Brandão, T.; Hipólito, J.; Ros, A.; Nunes, O. Emotion regulation, resilience, and mental health: A mediation study with university students in the pandemic context. Psychol. Sch. 2024, 61, 304–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Nishinaka, H.; Matsumoto, Y. Relationship between resilience, anxiety, and social support resources among Japanese elementary school students. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 7, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Oishi, S.; Kashdan, T.B. Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Feng, R.; Fu, Y.-N.; Liu, Q.; He, Y.; Turel, O.; He, Q. The bidirectional relationship between basic psychological needs and meaning in life: A longitudinal study. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2022, 197, 111784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, H.-J. Meaning in life, life role importance, life strain, and life satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 29905–29917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçın, I. Relationships among life satisfaction, meaning in life and need satisfaction with mixture structural equation modelling. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2023, 51, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadden, B.W.; Smith, C.V. I gotta say, today was a good (and meaningful) day: Daily meaning in life as a potential basic psychological need. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 20, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoidbach, J.; Berry, E.V.; Hansenne, M.; Mikolajczak, M. Positive emotion regulation and well-being: Comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.M.I.; Schutte, N.S.; Thorsteinsson, E.B. Be happy: The role of resilience between characteristic affect and symptoms of depression. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 15, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroope, S.; Draper, S.; Whitehead, A.L. Images of a loving god and sense of meaning in life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 111, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk, K.C.; Hill, P.L.; Lapsley, D.K.; Talib, T.L.; Finch, H. Purpose, hope, and life satisfaction in three age groups. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Jiao, M.; Wei, W.; Hu, Y. The relationship between resilience and quality of life in advanced cancer survivors: Multiple mediating effects of social support and spirituality. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1207097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waugh, C.E.; Sali, A.W. Resilience as the ability to maintain well-being: An allostatic active inference model. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, E.Y.J.; Thomas, K.S.; Phoo, E.Y.M.; Ng, S.L. What predicts wellbeing amidst crisis? A study of promotive and protective psychological factors among Malaysians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Wellbeing 2022, 12, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedhu, Y. Psychological resilience in the religious life: Conceptual framework and efforts to develop it. J. Narrat. Lang. Stud. 2023, 34, 3841–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, F. Savoring Beliefs Inventory (SBI): A scale for measuring beliefs about savouring. J. Ment. Health 2003, 12, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzler, A.L.; Ramsey, M.A.; Yi, C.Y.; Palmer, C.A.; Morey, J.N. Young adolescents’ emotional and regulatory responses to positive life events: Investigating temperament, attachment, and event characteristics. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Klibert, J.J.; Tarantino, N.; Lamis, D.A. Savouring and Self-compassion as Protective Factors for Depression. Stress Health 2017, 33, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sytine, A.I.; Britt, T.W.; Pury, C.L.; Rosopa, P.J. Savouring as a moderator of the combat exposure–mental health symptoms relationship. Stress Health 2018, 34, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Kim, S.; Pitts, M.J. Promoting subjective well-being through communication savoring. Commun. Q. 2021, 69, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Bryant, F.B. The benefits of savoring life: Savoring as a moderator of the relationship between health and life satisfaction in older adults. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2016, 84, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, S.L.; Reis, H.T.; Impett, E.A.; Asher, E.R. What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, P.J.; Morey, J.N.; Segerstrom, S.C. Beliefs about savoring in older adulthood: Aging and perceived health affect temporal components of perceived savoring ability. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 105, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, P.K.; Allan, B.A. Social Class as a Moderator of Positive Characteristics and Subjective Well-being: A Test of Resilience Theory. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 7, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, M.A.; Fredrickson, B.L. In search of durable positive psychology interventions: Predictors and consequences of long-term positive behavior change. J. Posit. Psychol. 2010, 5, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherry, S.B.; Hewitt, P.L.; Flett, G.L.; Harvey, M. Perfectionism dimensions, perfectionistic attitudes, dependent attitudes, and depression in psychiatric patients and university students. J. Couns. Psychol. 2003, 50, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, L.; Zhao, B.; Wang, D. Teacher support and mental well-being in chinese adolescents: The mediating role of negative emotions and resilience. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.A.; Masters, K.S.; Park, C.L. A meaningful life is a healthy life: A conceptual model linking meaning and meaning salience to health. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2018, 22, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Farb, N.A.; Goldin, P.R.; Fredrickson, B.L. The mindfulness-to-meaning theory: Extensions, applications, and challenges at the attention–appraisal–emotion interface. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, K.L.; Lovegrove, P.J.; Steger, M.F.; Chen, P.Y.; Cigularov, K.P.; Tomazic, R.G. The potential role of meaning in life in the relationship between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Nie, Q.; Zhou, J. The relationship between bullying victimization and online game addiction among Chinese early adolescents: The potential role of meaning in life and gender differences. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seon, Y.; Smith-Adcock, S. School belonging, self-efficacy, and meaning in life as mediators of bullying victimization and subjective well-being in adolescents. Psychol. Sch. 2021, 58, 1753–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silton, R.L.; Kahrilas, I.J.; Skymba, H.V.; Smith, J.; Bryant, F.B.; Heller, W. Regulating positive emotions: Implications for promoting well-being in individuals with depression. Emotion 2020, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sariçam, H. Life satisfaction: Testing a structural equation model based on authenticity and subjective happiness. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 46, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Hollinger-Smith, L. Savoring, resilience, and psychological well-being in older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Nezlek, J.B. Whether, when, and how is spirituality related to well-being? moving beyond single occasion questionnaires to understanding daily process. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, L.A.; Hicks, J.A.; Krull, J.L.; Del Gaiso, A.K. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P. Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, H.; Magyaródi, T.; Vargha, A.; Oláh, A. The Development of a Shortened Hungarian Version of the Savoring Beliefs Inventory. Mentálhigiéné Pszichoszomatika 2022, 23, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Lepper, H.S. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Weiss, A.; Shook, N.J. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and savoring: Factors that explain the relation between perceived social support and well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 152, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım, M.; Solmaz, F. COVID-19 burnout, COVID-19 stress and resilience: Initial psychometric properties of COVID-19 Burnout Scale. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuv-Ami, A.; Bareket-Bojmel, L. What indicates your life is meaningful? A new measure for the indicators of meaning in life (3IML). J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagi, L.; Bareket-Bojmel, L.; Tziner, A.; Icekson, T.; Mordoch, T. Social Support and Well-being among Relocating Women: The Mediating Roles of Resilience and Optimism. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 37, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, M.A.; Gentzler, A.L. Age differences in subjective well-being across adulthood: The roles of savoring and future time perspective. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2014, 78, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Thielking, P.; Thomas, E.A.; Coombs, M.; White, S.; Lombardi, J.; Beck, A. Linking dispositional mindfulness and positive psychological processes in cancer survivorship: A multivariate path analytic test of the mindfulness-to-meaning theory. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, M.T. Assessing and promoting resilience: An additional tool to address the increasing number of college students with psychological problems. Coll. Couns. 2012, 15, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Fredrickson, B.L. Positive psychological states in the arc from mindfulness to self-transcendence: Extensions of the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory and applications to addiction and chronic pain treatment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpfer, K.L. Factors and Processes Contributing to Resilience. In Resilience and Development. Longitudinal Research in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary Series; Glantz, M.D., Johnson, J.L., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Sheldon, K.M. Clarifying the concept of well-being: Psychological need satisfaction as the common core connecting eudaimonic and subjective well-being. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2019, 23, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifeagwazi, C.M.; Chukwuorji, J.C.; Zacchaeus, E.A. Alienation and psychological wellbeing: Moderation by resilience. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 120, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Fleury, M.-J.; Xiang, Y.-T.; Li, M.; D’arcy, C. Resilience and protective factors among people with a history of child maltreatment: A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steger, M.F.; Kashdan, T.B.; Sullivan, B.A.; Lorentz, D. Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. J. Pers. 2008, 76, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, K.A. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evid.-Based Dent. 2006, 7, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, E.R.; Yousaf, O.; Vittersø, A.D.; Jones, L. Dispositional mindfulness and psychological health: A systematic review. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, H.K.; Williams, P.G. Dispositional mindfulness: A critical review of construct validation research. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) savoring belief | 5.937 | 0.892 | 1 | −0.802 | 0.578 | |||

| (2) resilience | 3.376 | 0.948 | 0.235 *** | 1 | −0.296 | −0.232 | ||

| (3) meaning in life | 3.430 | 0.726 | 0.419 *** | 0.504 *** | 1 | −0.418 | 0.171 | |

| (4) happiness | 4.737 | 1.342 | 0.526 *** | 0.517 *** | 0.698 *** | 1 | −0.566 | 0.210 |

| Regression | Model Index | Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Independent Variables | R2 | F | β | t |

| resilience | savoring belief | 0.050 | 37.792 *** | 0.235 | 5.726 *** |

| meaning in life | savoring belief | 0.349 | 149.610 *** | 0.317 | 9.045 *** |

| resilience | 0.428 | 12.201 *** | |||

| happiness | savoring belief | 0.587 | 264.080 *** | 0.276 | 9.231 *** |

| resilience | 0.212 | 6.727 *** | |||

| Paths | Full | |

|---|---|---|

| Effect | 95% CI | |

| Total effect | 0.525 | [0.684, 0.897] |

| Direct effects | 0.416 | [0.327, 0.505] |

| Indirect effect | ||

| Total indirect effects | 0.374 | [0.295, 0.461] |

| savoring belief → resilience →happiness | 0.075 | [0.041, 0.115] |

| savoring belief → meaning in life →happiness | 0.227 | [0.169, 0.292] |

| savoring belief → resilience → meaning in life →happiness | 0.072 | [0.044, 0.105] |

| Demographic Variables | N | Savoring Belief Inventory (SBI) | Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS) | Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) | Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | F/t | M | SD | F/t | M | SD | F/t | M | SD | F/t | ||

| Gender 1. Female 2. Male | 358 203 | 5.990 5.833 | 0.822 0.822 | 2.169 * | 4.713 4.685 | 1.239 1.348 | 0.251 | 3.224 3.597 | 0.935 0.823 | −4.735 *** | 3.417 3.373 | 0.669 0.691 | 0.727 |

| Grade 1. Freshman 2. Sophomore 3. Junior Year 4. Senior Year | 121 128 158 154 | 5.798 5.984 5.935 5.997 | 0.862 0.677 0.630 0.641 | 1.565 | 4.490 4.709 4.785 4.782 | 1.360 1.213 1.238 1.298 | 1.537 | 3.252 3.303 3.474 3.371 | 0.856 0.942 0.960 0.878 | 1.554 | 3.306 3.358 3.471 3.439 | 0.737 0.638 0.641 0.688 | 1.712 |

| Major 1. A 2. B | 209 352 | 5.902 5.952 | 0.790 0.846 | −0.688 | 4.651 4.734 | 1.268 1.284 | −0.744 | 3.434 3.314 | 0.905 0.917 | 1.499 | 3.335 3.440 | 0.693 0.665 | −1.782 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, D.-F.; Huang, K.-W.; Ho, W.-S.; Cheng, Y.-C. Savoring Belief, Resilience, and Meaning in Life as Pathways to Happiness: A Sequential Mediation Analysis among Taiwanese University Students. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14050388

Chen D-F, Huang K-W, Ho W-S, Cheng Y-C. Savoring Belief, Resilience, and Meaning in Life as Pathways to Happiness: A Sequential Mediation Analysis among Taiwanese University Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(5):388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14050388

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Der-Fa, Kai-Wen Huang, Wei-Sho Ho, and Yao-Chung Cheng. 2024. "Savoring Belief, Resilience, and Meaning in Life as Pathways to Happiness: A Sequential Mediation Analysis among Taiwanese University Students" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 5: 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14050388

APA StyleChen, D.-F., Huang, K.-W., Ho, W.-S., & Cheng, Y.-C. (2024). Savoring Belief, Resilience, and Meaning in Life as Pathways to Happiness: A Sequential Mediation Analysis among Taiwanese University Students. Behavioral Sciences, 14(5), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14050388