Measuring Attributions 50 Years on: From within-Country Poverty to Global Inequality

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Measuring Attributions—A Brief History

1.2. The Present Research

- On which domains do the scales focus (i.e., attributions of domestic poverty, global poverty, domestic inequality, or global inequality)?

- On which theoretical approaches are the scales assessing poverty and inequality attributions based?

- Which dimensions of attributions are covered?

- In what countries were the samples collected?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

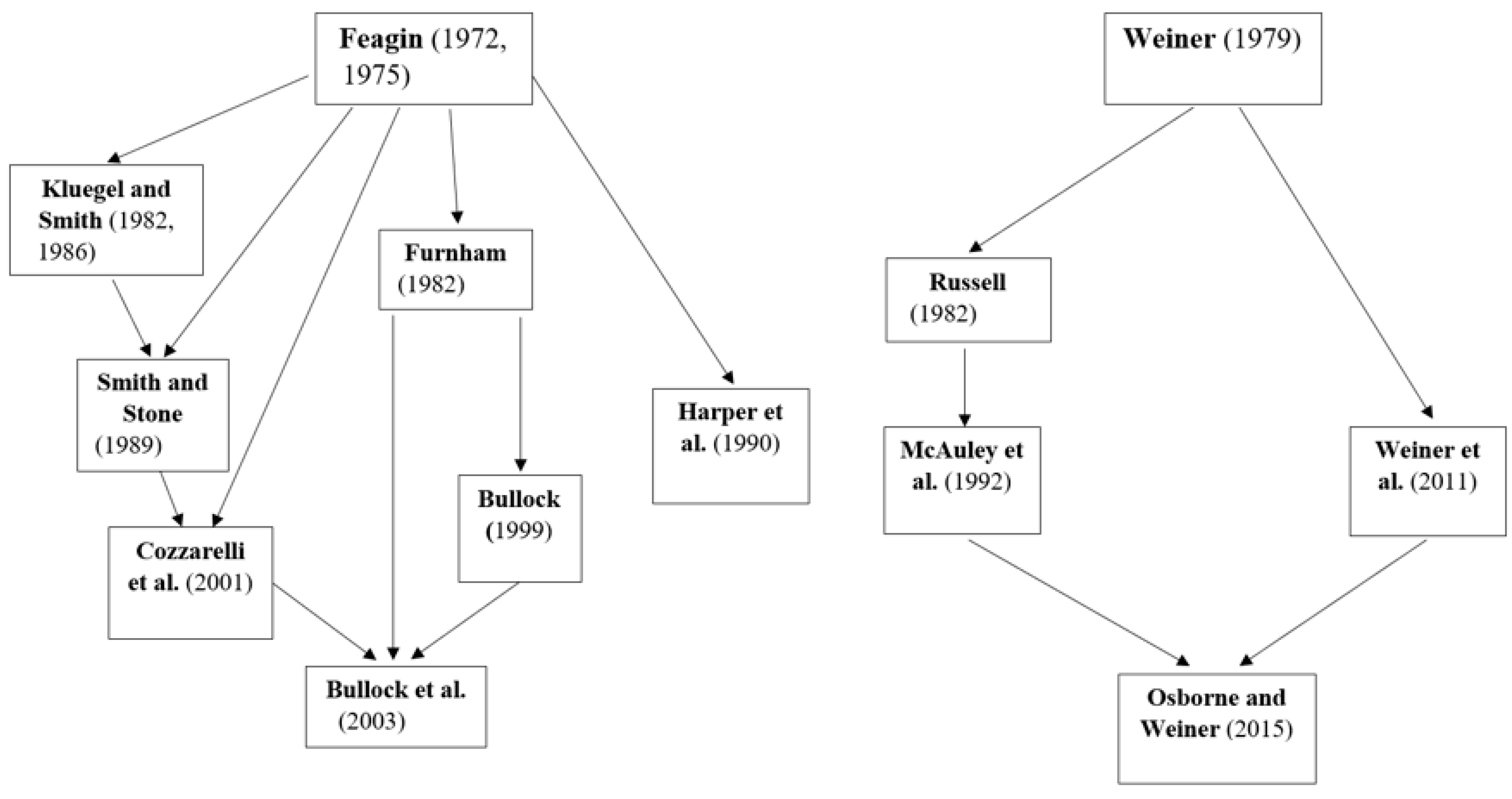

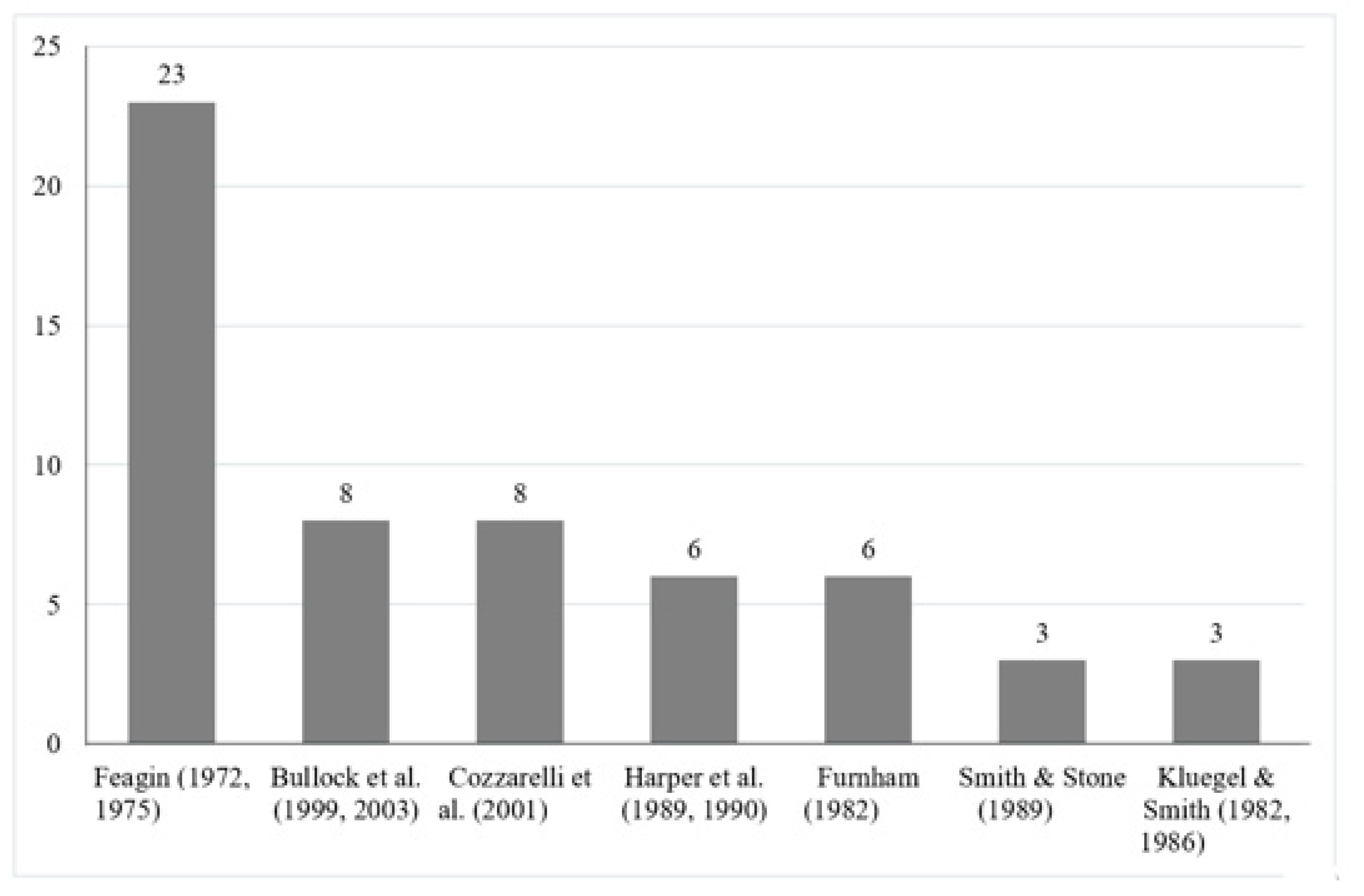

3.2. Theoretical Influences

3.3. Dimensionality of Poverty and Inequality Attributions

4. Discussion

4.1. From A Domestic to A Global Perspective

4.2. From Locus to Controllability

4.3. From Poverty to Inequality

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Search Engine and Databases | Keyword Combination | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | poverty AND attributions | 113 |

| poverty AND attribution | 40 | |

| poor AND attributions | 50 | |

| poor AND attribution | 44 | |

| inequality AND attributions | 23 | |

| inequality AND attribution | 16 | |

| pobreza AND atribuciones | 28 | |

| pobreza AND atribución | 3 | |

| pobre AND atribuciones | 1 | |

| pobre AND atribución | 0 | |

| desigualdad AND atribuciones | 1 | |

| desigualdad AND atribución | 1 | |

| Total | 320 | |

| EBSCO host (including APA PsycArticles, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, APA PsycInfo, PSYNDEX Literature with PSYNDEX Tests) | poverty AND attributions | 73 |

| poverty AND attribution | 73 | |

| poor AND attributions | 31 | |

| poor AND attribution | 31 | |

| inequality AND attributions | 14 | |

| inequality AND attribution | 14 | |

| pobreza AND atribuciones | 4 | |

| pobreza AND atribución | 0 | |

| pobre AND atribuciones | 1 | |

| pobre AND atribución | 0 | |

| desigualdad AND atribuciones | 0 | |

| desigualdad AND atribución | 0 | |

| Total | 241 |

| № | Authors and Year of Publication | Scope of Attributions | Sample Country | Sample Size and Profile | Theoretical Reference | № of Items and Scale Response Anchors | Dimensions and Their Reliability * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abouchedid and Nasser (2002) [89] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Lebanon and Portugal | 372 university students | Feagin (1972; 1975) [10,34] | 15 items, 1–5 (disagree–agree) | Lebanon: structural (α = 0.63), individualist (α = 0.67), fatalist (α = 0.67); Portugal: structural (α = 0.54), individualist (α = 0.70), fatalist (α = 0.77) |

| 2 | Alcañiz-Colomer, Moya, and Valor-Segura (2023) [90] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Spain | 484 (study 1, survey respondents); 256 (study 2, undergraduate students); 358 (study 3, survey respondents) | Furnham, (1982) [31], Weiner et al., (2011) [23] | 20 items, 1–5 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) + 4 items for the Spanish context | Individualistic (α = 0.80/0.83/0.71), structural (α = 0.81/0.81) |

| 3 | Bai, Xu, Yang, and Guo (2023) [91] | Domestic poverty or without specification | China | 448 (study 1) | Li (2014) [92] | 16 items, 1–7 (totally disagree–totally agree) | Internal (α = 0.79), external (α = 0.76) |

| 4 | Bennett, Raiz, and Davis (2016) [27] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 209 social workers | Bullock (2004) [68], Bullock et al., (2003a) [29], Weiss-Gal and Gal (2007) [93] | 33 items, 1–6 (fully agree–fully disagree) | Individual (α = 0.94), structural (α = 0.88), cultural (α = 0.77) |

| 5 | Bergmann and Todd (2019) [94] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 189 (study 1) and 646 (study 2) university students | Cozzarelli et al., (2001) [26] | 13 items, 1–5 (not important at all–extremely important) | Internal (α = 0.83), external (α = 0.80) |

| 6 | Bobbio, Canova, and Manganelli (2010) [95] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Italy | 181 university students | Feagin (1972) [10], Smith and Stone (1989) [37] | 12 items, 1–5 (not important at all–extremely important) | Internal/individualistic (α = 0.82), external/structuralistic (α = 0.74) |

| 7 | Bradley and Cole (2002) [96] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Canada and the USA | 714 survey respondents aged 18 or older | Feagin (1975) [34] | 11 items, 1–3 (very important–not important at all) | Internal (α = 0.60), external (α = 0.62) |

| 8 | Bullock (1999) [30] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 236 survey respondents | Furnham (1982) [31] | 16 items, 1–7 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) | Individualistic, structural, structural–fatalistic |

| 9 | Bullock, Williams, and Limbert (2003) [29] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 131 university students | Bullock (1999) [30], Cozzarelli et al., (2001) [26], Furnham (1982) [31] | 45 items, 1–7 (disagree–agree) | Structural (α = 0.91), individualistic/poverty culture (α = 0.91), fatalistic/structural (α = 0.72) |

| 10 | Canto, Perles, and San Martín (2012) [97] | Global poverty | Spain | 300 university students | Hine and Montiel (1999) [7], adapted by Betancor et al., (2002) [98] | 22 items, 1–6 (fully disagree–fully agree) | Structural, personal, fatalistic |

| 11 | Carr, Taef, De M.S. Ribeiro and MacLachlan (1998) [99] | Global poverty | Australia and Brazil | 100 textile workers | Harper et al., (1990) [32] | 16 items, 1–5 (disagree–agree) | Nature, the poor, local governments, exploitation |

| 12 | Carr and MacLachlan (1998) [100] | Global poverty | Australia and Malawi | 582 university students | Harper et al., (1990) [32] | 20 items, 1–5 (disagree–agree) | Blame the poor, blame international exploitation, blame nature, blame third-world governments |

| 13 | Castillo and Rivera-Gutiérrez (2018) [74] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Chile | 1245 survey respondents aged 18 or older | Feagin (1972) [10] | 5 items, 1–5 (never–always) | Internal/individual, external/sociocultural |

| 14 | Cheng and Ngok (2023) [101] | Domestic poverty or without specification | China | 10,855/10,678 survey respondents | Feagin (1972) [10] | 5 items (dummy variables) | Individualistic, structural, fatalistic |

| 15 | Cojanu and Stroe (2017) [102] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Romania | 600 beneficiaries of guaranteed minimum income | N/A | 10 items, 1–2 (ordinal scale) | Individual, structural/societal, fatalistic |

| 16 | Cozzarelli, Wilkinson, and Tagler (2001) [26] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 209 university students | Feagin (1972) [10], Smith and Stone (1989) [37] | 22 items, 1–5 (not important at all–very important) | Internal (α = 0.75), external (α = 0.79), cultural (α = 0.65) |

| 17 | da Costa and Dias (2013) [57] | Domestic poverty or without specification | 13 European countries | 15,504 respondents above age 15 | N/A | 11 items (dummy variables) | Individualistic/internal, structural, Fatalist |

| 18 | Davidai (2018) [103] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 397 survey respondents | Kluegel and Smith (1986) [36] | 7 items, 1–7 (not so important–extremely important) | Internal, external |

| 19 | Engler, Strassle, and Steck (2019) [104] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 161 primary and secondary education administrative employees | Cozzarelli et al., (2001) [26] | 22 items | Internal, external |

| 20 | Frei, Castillo, Herrera, and Suárez (2020) [105] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Chile | 2954 survey respondents aged 18 or older | N/A | 10 items, 1–2 (ordinal scale) | Internal, external, ambivalent |

| 21 | Gatica and Navarro-Lashayas (2019) [106] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Spain | 184 university students | Bullock et al., (2003) [29] | 32 items, 1–5 (not important–very important) | Sociostructural (α = 0.91), individual (α = 0.91), fatalistic (α = 0.72) |

| 22 | Generalao (2005) [107] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Philippines | 373 housewives (145 from rural areas and 228 from urban areas) | Weiner (1985) [14] | 7 items, 1–5 (semantic differential scale) | Locus, controllability, Stability |

| 23 | Gonzalez, Macchia, and Whillans (2022) [108] | Domestic inequality or without specification | USA | 200 survey respondents | Hussak and Cimpian (2015) [109] | 3 items (forced choice) | Uncontrollable dispositional/controllable dispositional/uncontrollable situational |

| 24 | Griffin and Oheneba-Sakyi (1993) [110] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 207 undergraduate students | N/A | 1 item (dummy variable) | Individual |

| 25 | Habibov, Cheung, Auchynnikava, and Fan (2017) [58] | Domestic poverty or without specification | 24 European and Asian countries | 37,307 survey respondents aged 17 or older | N/A | 1 item (dummy variable) | Structural |

| 26 | Halik, Malek, Bahari, Matshah, and Webley (2012) [111] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Malaysia | 124 university students | Feagin (1972) [10], Furnham (1982) [31] | 16 items, 1–5 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) | Individualistic (α = 0.71), structural (α = 0.63), fatalistic (α = 0.58) |

| 27 | Heaven (1989) [112] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Australia | 285 survey respondents aged 18 or older | Feagin (1972) [10], Furnham (1982) [31] | 11 items | Societal (α = 0.72), negative individualistic (α = 0.75), characterological (α = 0.66) |

| 28 | Hill, Toft, Garrett, Ferguson, and Kuechler (2016) [113] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 337 university students | Feagin (1972; 1975) [10,34] | 7 items, 1–5 (agree–disagree) | Individual (α = 0.66), structural (α = 0.70) |

| 29 | Husz, Kopasz, and Medgyesi (2022) [114] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Hungary | 600 social workers | Feagin (1972) [10] | 10 items, 1–4 (strongly agree–strongly disagree) | Structural, individualistic |

| 30 | Ige and Nekhwevha (2012) [115] | Domestic poverty or without specification | South Africa | 383 survey respondents | Feagin (1972) [10] | 38 items, 1–5 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) | Structural (α = 0.86), individual (α = 0.91), fatalistic (α = 0.85) |

| 31 | Kafetsios and Kateri (2022) [116] | Domestic inequality or without specification | Greece | 846 survey respondents | N/A | 12 items | Dispositional, contextual |

| 32 | Kitchens, Ricks, and Hannor-Walker (2020) [117] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 91 university students | Bullock (1999) [30] | 36 items, 1–5 (not at all important as a cause of poverty–extremely important as a cause of poverty) | Individualistic (α = 0.91), structuralistic (α = 0.91), fatalistic (α = 0.72) |

| 33 | Landmane and Reņģe (2010) [118] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Latvia | 202 women | Bullock et al., (2003) [29], Bullock (2004) [68] | 30 items, 1–5 (strong disagreement–strong agreement) | Family/fatalistic (α = 0.86), individualistic (α = 0.79), structural (α = 0.77) |

| 34 | Lee, Park, Rhee, Kim, Lee, Ha, Baik, and Ahn (2021) [119] | Domestic poverty or without specification | South Korea, Japan, USA | 2213 survey respondents representative of each country’s population | Feagin (1972, 1975) [10,34] | 8 items, 1–5 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) | Individualistic (α = 0.79), societal (α = 0.64) |

| 35 | Ljubotina and Ljubotina (2007) [120] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Croatia | 365 university students | Feagin (1975) [34] | 24 items, 1–5 (completely disagree–completely agree) | Individual (α = 0.76), structural (α = 0.79), fatalistic (α = 0.70), micro-environmental/cultural (α = 0.65) |

| 36 | McWha and Carr (2009) [121] | Global poverty | New Zealand | 171 university students | Harper et al., (1990) [32] | 17 items, 1–5 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) | Blame the poor (α = 0.77), blame third-world governments (α = 0.70), blame nature (α = 0.56) |

| 37 | Mickelson and Hazlett (2014) [54] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 66 low-income women with at least one child aged 1–6 years | Bullock et al., (2003) [29] | 37 items, 1–5 (did not contribute at all–contributed a lot) | Structural (α = 0.90), individualistic (α = 0.76), children (α = 0.71), romantic relationships (α = 0.66), fatalistic (α = 0.65) |

| 38 | Murry, Brody, Brown, Wisenbaker, Cutrona, and Simons (2002) [122] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 96 single mothers who receive government welfare | Conger (1995) [123] | 16 items, 1–4 (agree–disagree) | External (α total = 0.76) |

| 39 | Nasser (2007) [124] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Lebanon | 242 high-school students | Feagin (1972) [10] | N/A | Structuralistic, individualistic, fatalistic |

| 40 | Nasser and Abouchedid (2001) [125] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Lebanon | 232 university students | Feagin (1972) [10], Hunt (1996) [65], Morcol (1997) [126], Griffin and Oheneba-Sakyi (1993) [110], Williamson (1974) [127] | 15 items, 1–5 (strongly agree–strongly disagree) | Structuralist (α = 0.70), individualist status quo (α = 0.60), fatalist (α = 0.70), individual blaming the poor/societal (α = 0.50) |

| 41 | Nasser and Abouchedid (2006) [128] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Lebanon, South Africa | 443 university students | Feagin (1972) [10] | 15 items, 1–5 (strongly agree–strongly disagree) | Individualism (α = 0.71), fatalism (α = 0.62), structuralism (α = 0.50) |

| 42 | Nasser, Singhal, and Abouchedid (2005) [129] | Domestic poverty or without specification | India | 365 high-school and university students | Feagin (1972) [10], adapted by Nasser and Abouchedid (2001) [125] | 17 items, 1–5 (fully agree–fully disagree) | Individualistic, structural, fatalistic (α total = 0.63) |

| 43 | Nelson and Joselus (2023) [130] | Domestic inequality or without specification | USA | 448 survey respondents | Peffley, Hurwitz, and Mondak (2017) [131] | 7 items, 1–6 (not important at all–extremely important) | Internal (α = 0.915), cultural (α = 0.906), external |

| 44 | Niemelä (2011) [39] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Finland | 2006 social security officials and other citizens | Feagin (1972) [10], van Oorschot and Halman (2000) [50], Saunders (2003) [132] | 11 items, 1–5 (strongly agree–strongly disagree) | Individual, individual–structural, structural, fatalistic |

| 45 | Norcia, Castellani, and Rissotto (2010) [133] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Italy | 1914 survey respondents | N/A | 7 items, 1–5 (never–very often) | Internal, external, fatalism |

| 46 | Norcia and Risotto (2011) [134] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Italy | 1914 survey respondents | N/A | 7 items, 1–5 | Powerful others, chance, internal |

| 47 | Norcia and Rissotto (2015) [55] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Italy | 992 survey respondents | N/A | 8 items, 1–5 | Internal (α = 0.57), powerful other (α = 0.66), chance (α = 0.63) |

| 48 | Osborne and Weiner (2015) [22] | Domestic poverty or without specification | New Zealand and the USA | 315 university students | McAuley et al., (1992) [25] | 12 items, 1–7 (semantic differential scale) | Locus (α = 0.79), stability (α = 0.65), personal control (α = 0.83), other control (α = 0.71) |

| 49 | Özpinar and Akdede (2022) [135] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Turkey | 1110 participants | Feagin (1972) [10] | 7 items (dummy variables) | Individualistic, Structural, Fatalistic |

| 50 | Pandey, Sinha, Prakash, and Tripathi (1982) [136] | Domestic poverty or without specification | India | 90 university students | Sinha et al., (1980) [137] | 8 items, 1–5 (completely disagree–completely agree) | Self, fate, governmental policies, economic dominance |

| 51 | Piff, Wiwad, Robinson, Aknin, Mercier, and Shariff (2020) [8] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 602 survey respondents | Feagin (1972) [10], Kluegel and Smith (1986) [36] | 12 items, 1–5 (not so important–extremely important) | Situational attributions (α = 0.85), dispositional attributions (α = 0.79) |

| 52 | Reutter, Veenstra, Stewart, Raphael, Love, Makwarimba, and McMurray (2006) [138] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Canada | 1671 survey respondents | van Oorschot and Halman (2000) [50] | 5 items, 1–5 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) | Structural, sociocultural, individualistic, fatalistic |

| 53 | Reyna, Acosta, Saavedra, and Correa (2018) [139] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Argentina | 280 survey respondents | Cozzarelli et al., (2001) [26] | 23 items, 1–5 (not important for poverty–extremely important as a poverty cause) | Internal (α = 0.77), sociostructural (α = 0.76), fatalistic (α = 0.69) |

| 54 | Reyna and Reparaz (2014) [28] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Argentina | 177 university students | Cozzarelli et al., (2001) [26] | 23 items, 1–5 (not important for poverty–extremely important as a poverty cause) | Internal (α = 0.74), external (α = 0.73), cultural (α = 0.79) |

| 55 | Ríos-Rodríguez, Moreno-Jiménez, and Vallejo Martín (2022) [140] | Global poverty | Spain | 720 survey respondents | N/A | 17 items | Cultural learning (α = 0.80), factic, (α = 0.82), deterministic (α = 0.71) |

| 56 | Robinson (2011) [53] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 839 survey respondents (431 social workers and 408 school teachers) | Feagin (1975) [34], Kluegel and Smith (1982) [36] | 11 items | Individual (α = 0.70), structural (α = 0.72), psycho/medical (α = 0.63), family/morals (α = 0.68) |

| 57 | Sainz, García-Castro, Jiménez-Moya, and Lobato (2023) [141] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Mexico | 523 survey respondents | Cozzarelli et al., (2001) [26] | 11 items, 1–7 (not at all–completely) | Internal (α = 0.88), external (α = 0.80) |

| 58 | Schneider and Castillo (2015) [48] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Germany | 3059 survey respondents (715 from East Germany and 2344 from West Germany) | N/A | 5 items, 1–5 (very often–never) | Internal, external |

| 59 | Segretin, Reyna, and Lipina (2022) [142] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Argentina | 1659 survey respondents | Bolitho et al., (2007) [143], Cozzarelli et al., (2001) [26], Ige and Nekhwevha, (2014) [144], Reyna and Reparaz, (2014) [28], Vázquez et al., (2010) [33], Weiss-Gal et al., (2009) [52] | 32 items, 1–5 (not important for poverty–extremely important as a poverty cause) | Internal or individualistic (α = 0.90), external or structural (α = 0.90) |

| 60 | Sigelman (2012) [56] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 88 primary education students | N/A | 9 items, 1–5 (no–yes) | Competence (α = 0.79), social attractiveness (α = 0.81), physical attractiveness (α = 0.68) |

| 61 | Smith and Kluegel (1979) [49] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 175 respondents aged 18 or older | Feagin (1972) [10] | N/A | Structural (α = 0.62), individual (α = 0.77) |

| 62 | Stoeffler, Kauffman, and Joseph (2021) [145] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 1037 social work educators | Bullock et al., (2003) [29] | 41 items, 1–7 (strong agreement–strong disagreement) | Structural, individual, fatalistic |

| 63 | Swami, Voracek, Furnham, Robinson and Tran (2023) [146] | Domestic poverty or without specification | UK | 392 respondents | Yun and Weaver (2010) [147] | 21 items, 1–5 (fully disagree–fully agree) | Individualistic; discriminatory; structural (reliability across subscales, McDonald’s ω = 0.91) |

| 64 | Terol-Cantero, Martin-Aragón Gelabert, Costa-López, Manchón López, and Vázquez-Rodríguez (2023) [148] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Spain | 278 university students | Cozzarelli et al., (2001) [26], Reyna and Reparaz (2014) [28] | 23 items, 1–5 (not at all important–extremely important) | Cultural (α = 0.69), internal (α = 0.73), external (α = 0.77) |

| 65 | Toporek and Pope-Davis (2005) [66] | Domestic poverty or without specification | USA | 158 master’s students | Smith and Stone (1989) [37] | 19 items, 1–3 (is not important–is very important) | Individualism (α = 77), structuralism/situationalism (α = 72). |

| 66 | Vázquez and Panadero (2007) [149] | Global poverty | Spain and Nicaragua | 294 university students | Harper et al., (1990) [32] | 25 items, 1–5 (fully disagree–fully agree) | Dispositional, situational |

| 67 | Vázquez and Panadero (2009) [150] | Global poverty | Spain and Nicaragua | 294 university students | Harper et al., (1990) [32] | 25 items, 1–5 (fully disagree–fully agree) | Dispositional, situational |

| 68 | Vázquez, Panadero, Pascual, and Ordoñez (2017) [59] | Global poverty | Spain | 1092 university students | Harper (2002) [32], Hine et al., (2005) [151], Vázquez and Panadero (2009) [150] | 50 items, –2–+2 (fully disagree–fully agree) | Fault of the world economic structure; fault of fate, nature, cultural habits, and political misconduct; fault of the developing countries’ population |

| 69 | Vilchis Carrillo (2022) [152] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Mexico | 1403 survey respondents | N/A | 3 items (dichotomous response) | Structural, individualistic, fatalistic |

| 70 | Waddell, Wright, Mendel, Dys-Steenbergen, and Bahrami (2023) [9] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Canada | 337 undergraduate students (study 1), 203 undergraduate students (study 2) | Furnham (1982) [31] | 9/10 items, 1–7 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) | Internal (α = 0.77), external (α = 0.65) |

| 71 | Weiss-Gal, Gal, Benyamini, Ginzburg, Savaya, and Peled (2009) [52] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Israel | 811 survey respondents (401 clients and 410 social workers) | Weiss-Gal (2005) [51], Weiss-Gal et al., (2003) [153], Bullock et al., (2003) [29] | 25 items, 1–5 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) | Psychological (α = 0.89), motivational (α = 0.87), sociostructural (α = 0.82), fatalistic (α = 0.78) |

| 72 | Wollie (2009) [154] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Ethiopia | 460 high-school and university students | Feagin (1972) [10], Nasser and Abouchedid (2001) [125], Nasser et al., (2005) [129] | 39 items, 1–5 (strongly disagree–strongly agree) | Individualistic, structural, fatalistic |

| 73 | Yeboah and Ernest (2012) [155] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Ghana | 147 university students | N/A | N/A | Individual, structural, fatalistic |

| 74 | Yúdica, Bastias, and Etchezahar (2021) [44] | Domestic poverty or without specification | Argentina | 331 secondary school students | Gatica et al., (2017) [156], based on Bullock et al., (2003) [29] | 32 items; 1–5 (not at all important–very important) | Individualistic (α = 0.81); structural (α = 0.80); fatalistic (α = 0.61) |

References

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2021–2022. Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping Our Future in a Transforming World; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout, E.; Galasso, N.; Lawson, M.; Rivero Morales, P.A.; Taneja, A.; Vázquez Pimentel, D.A. The Inequality Virus: Bringing Together a World Torn Apart by Coronavirus through a Fair, Just and Sustainable Economy; OXFAM: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, G.; Berthold, A.; Steffens, M.C. We are the world—and they are not: Prototypicality for the world community, legitimacy, and responses to global inequality. Polit. Psychol. 2012, 33, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, G.; Proch, J.; Cohrs, J.C. Individual differences in responses to global inequality. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2014, 14, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, G.; Jacob, L. Principles of environmental justice and pro-environmental action: A two-step process model of moral anger and responsibility to act. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 51, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, G.; Kohlmann, F. Feeling global, acting ethically: Global identification and fairtrade consumption. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 155, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hine, D.W.; Montiel, C.J. Poverty in developing nations: A cross-cultural attributional analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, P.K.; Wiwad, D.; Robinson, A.R.; Aknin, L.B.; Mercier, B.; Shariff, A. Shifting attributions for poverty motivates opposition to inequality and enhances egalitarianism. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddell, M.W.; Wright, S.C.; Mendel, J.; Dys-Steenbergen, O.; Bahrami, M. From passerby to ally: Testing an intervention to challenge attributions for poverty and generate support for poverty-reducing policies and allyship. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2023, 23, 334–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagin, J.R. Poverty: We still believe that God helps those who help themselves. Psychol. Today 1972, 6, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Vasudeva, P.N. A factorial study of the perceived reasons for poverty. Asian J. Psychol. Educ. 1977, 2, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Feather, N.T. Explanations of poverty in Australian and American samples: The person, society, or fate? Aust. J. Psychol. 1974, 26, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. A Theory of motivation for some classroom experiences. J. Educ. Psychol. 1979, 71, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, B. An attributional theory of achievement, motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1985, 92, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, G.S.; Weiner, B. Conservatism and perceptions of poverty: An attributional analysis. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 925–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Williams, C. An Attributional Approach to Motivation in School. In Handbook of Motivation at School; Wentzel, C., Wigfield, A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Hall, N.C. A systematic review of teachers’ causal attributions: Prevalence, correlates, and consequences. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marichal, F.; Quiles, M.N. El estudio del estigma desde la atribución causal. Rev. Psicol. Social 1998, 13, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menec, V.H.; Perry, R.P. Reactions to stigmas among Canadian students: Testing an attribution-affect-help judgment model. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 138, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyndon, S. Troubling discourses of poverty in early childhood in the UK. Child. Soc. 2019, 33, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharaktschiew, N.; Rudolph, U. The who and whom of help giving: An attributional model integrating the help giver and the help recipient. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, D.; Weiner, B. A latent profile analysis of attributions for poverty: Identifying response patterns underlying people’s willingness to help the poor. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 85, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.; Osborne, D.; Rudolph, U. An attributional analysis of reactions to poverty: The political ideology of the giver and the perceived morality of the receiver. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 15, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.W. The Causal Dimension Scale: A measure of how individuals perceive. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 42, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E.; Duncan, T.E.; Russell, D.W. Measuring causal attributions: The revised causal dimension scale (CDSII). Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzarelli, C.; Wilkinson, A.V.; Tagler, M.J. Attitudes toward the poor and attributions for poverty. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.M.; Raiz, L.; Davis, T.S. Development and validation of the Poverty Attributions Survey. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2016, 52, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, C.; Reparaz, M. Propiedades psicométricas de las escalas de atribuciones sobre las causas de la pobreza y actitudes hacia los pobres. Actual. Psicol. 2014, 28, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bullock, H.E.; Williams, W.R.; Limbert, W.M. Predicting support for welfare policies: The impact of attributions and beliefs about inequality. J. Poverty 2003, 7, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, H.E. Attributions for poverty: A comparison of middle class and welfare recipient attitudes. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2059–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A. Why are the poor always with us? Explanations for poverty in Britain. Britain. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 21, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.J.; Wagstaff, G.F.; Newton, J.T.; Harrison, K.R. Lay causal perceptions of third world poverty and the just world. Soc. Behav. Pers. 1990, 18, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Cabrera, J.J.; Pascual, I.; Panadero Herrero, S. Developing the “Causes of Poverty in Developing Countries Questionnaire (CPDCQ)” in a Spanish-speaking population. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2010, 38, 1167–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagin, J.R. Subordinating Poor Persons: Welfare and American Beliefs; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kluegel, J.R.; Smith, E.R. Whites’ beliefs about blacks’ opportunity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1982, 47, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluegel, J.R.; Smith, E.R. Beliefs About Inequality: Americans’ Views of What Is and What Ought to Be; Aldine De Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.B.; Stone, L. Rags, riches, and bootstraps: Beliefs about the causes of wealth and poverty. Sociol. Q. 1989, 30, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.J. Poverty and Discourse. In Poverty and Psychology: From Global Perspective to Local Practice; Carr, S.C., Sloan, T.S., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä, M. Attributions for poverty in Finland: A non-generic approach. Res. Finn. Soc. 2011, 4, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Wither attribution theory? J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 603–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoban, I.A.; Şahin, F.; Uluocak, G.P.; Büyüköztürk, Ş. Turkish adaptation of the Chinese Perceived Causes of Poverty Scale. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 15, 564–572. [Google Scholar]

- Dakduk, S.; González, M.; Malavé, J. Percepciones acerca de los pobres y la pobreza: Una revisión. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2010, 42, 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D.T. Chinese people’s explanations of poverty: The Perceived Causes of Poverty Scale. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2003, 13, 622–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yúdica, L.; Bastias, F.; Etchezahar, E. Poverty attributions and emotions associated with willingness to help and government aid. Psihol. Teme 2021, 30, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepianka, D.; Van Oorschot, W.; Gelissen, J. Popular explanations of poverty: A critical discussion of empirical research. J. Soc. Policy 2009, 38, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babjaková, J.; Džuka, J.; Gresty, J. Perceived causes of poverty and subjective aspirations of the poor: A literature review. Ceskoslovenska Psychol. 2019, 63, 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S.M.; Castillo, J.C. Poverty attributions and the perceived justice of income inequality: A comparison of East and West Germany. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2015, 78, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.R.; Kluegel, J.R. Causal attributions outside the laboratory: Explaining poverty. In Proceedings of the American Sociological Association Session on Attribution, Cognitive, and Related Processes, Boston, MA, USA, 27–31 August 1979; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oorschot, W.; Halman, L. Blame or fate, individual or social? An international comparison of popular explanations of poverty. Eur. Soc. 2000, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss-Gal, I. Is there a global common core to social work? A cross-national comparative study of BSW graduate students. Soc. Work 2005, 50, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss-Gal, I.; Gal, J.; Benyamini, Y.; Ginzburg, K.; Savaya, R.; Peled, E. Social workers’ and service users’ causal attributions for poverty. Soc. Work. 2009, 54, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, G. The contradictions of caring: Social workers, teachers, and attributions for poverty and welfare reform. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 2374–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickelson, K.D.; Hazlett, E. “Why me?”: Low-income women’s poverty attributions, mental health, and social class perceptions. Sex Roles 2014, 71, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norcia, M.; Rissotto, A. Causal attributions for poverty in Italy: What do people think about impoverishment? OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 8, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman, C.K. Rich man, poor man: Developmental differences in attributions and perceptions. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2012, 113, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, L.P.; Dias, J.G. Perceptions of poverty attributions in Europe: A multilevel mixture model approach. Qual. Quant. 2013, 48, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibov, N.; Cheung, A.; Auchynnikava, A.; Fan, L. Explaining support for structural attribution of poverty in post-communist countries: Multilevel analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. J. Soc. Soc. Welf. 2017, 44, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Cabrera, J.J.; Panadero Herrero, S.; Pascual, I.; Ordoñez, X.G. Causal attributions of poverty in less developed countries: Comparing among undergraduates from nations with different development levels. Interam. J. Psychol. 2017, 51, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Baute, S.; Pellegata, A. Multi-level blame attribution and public support for EU welfare policies. West Eur. Polit. 2023, 46, 1369–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thalmayer, A.G.; Toscanelli, C.; Arnett, J.J. The neglected 95% revisited: Is American psychology becoming less American? Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.B. I made it because of me: Beliefs about the causes of wealth and poverty. Sociol. Spectr. 1985, 5, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. Toward a revised framework for examining beliefs about the causes of poverty. Sociol. Q. 1996, 37, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M. The individual, society, or both? A comparison of Black, Latino and White beliefs about the causes of poverty. Soc. Forces 1996, 75, 293–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toporek, R.L.; Pope-Davis, D.B. Exploring the relationships between multicultural training, racial attitudes, and attributions of poverty among graduate counselling trainees. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Min. Psychol. 2005, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastias, F.; Cañadas, B.; Figueroa, M.C.; Sosa, V.; Moya, M.J. Explanations about poverty origin according to professional training area. J. Educ. Psychol. Prop. Y Repres. 2019, 7, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, H.E. From the front lines of welfare reform: An analysis of social worker and welfare recipient attitudes. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 144, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, H.E.; Limbert, W.M. Scaling the socioeconomic ladder: Low-income women’s perceptions. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavega, E.; Kindle, P.A.; Peterson, S.; Schwartz, C. The blame index: Exploring the change in social work students’ perceptions of poverty. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2017, 53, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toikko, T.; Rantanen, T. How does the welfare state model influence social political attitudes? An analysis of citizens’ concrete and abstract attitudes toward poverty. J. Int. Comp. Soc. Policy 2017, 33, 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Judgments of Responsibility: A Foundation for a Theory of Social Conduct; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.C.; Rivera-Gutiérrez, M. Dimensiones comunes a las atribuciones de pobreza y riqueza. Psykhe 2018, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Lay, S. Sense of Responsibility and Empathy: Bridging the Gap between Attributions and Helping Behaviours. In Intergroup Helping; van Leeuwen, E., Zagefka, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 331–347. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Roche, J.M.; Ballon, P.; Foster, J.; Santos, M.E.; Seth, S. Multidimensional Poverty Measurement and Analysis; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Sobre conceptos y medidas de pobreza. Comer. Exter. 1992, 42, 310–322. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, M.J.; Cole, S.W.; Ravi, S.; Chumbley, J.; Xu, W.; Potente, C.; Levitt, B.; Bodeleta, J.; Aiellod, A.; Gaydoshmiy, L.; et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in molecular risk for chronic diseases observed in young adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2103088119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spicker, P. Definiciones de Pobreza: Doce Grupos de Significados. In Pobreza: Un Glosario Internacional; Spicker, P., Álvarez, S., Gordon, D., Eds.; Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales CLACSO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bastias, F.; Barreiro, A. Who is poor? Analysis of social representations in an Argentine sample. Psico-USF 2023, 28, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.A.; Jones, S.H.; Lewis, D.W. Public beliefs about the causes of homelessness. Soc. Forces 1990, 69, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepianka, D. Are the Poor to be Blamed or Pitied? A Comparative Study of Popular Poverty Attributions in Europe; Tilburg University: Tilburg, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas, O. Self-interest and the common good: The impact of norms, selfishness and context in social policy opinions. J. Socio-Econ. 1997, 26, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, N.; Landmann, H.; Cañadas, B.; Bastias, F.; Rohmann, A. What are the causes of global inequality? An exploration of global inequality attributions in Germany and Argentina. Community Psychol. Glob. Perspect. 2024, 10, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, A.; Serieux, J. All about the giants: Probing the influences on world growth and income inequality at the end of the 20th century. CESifo Econ. Stud. 2004, 50, 133–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanovic, B. Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. El Capital en el Siglo XXI; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, J. The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions; William Heinemann: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abouchedid, K.; Nasser, R. Attributions of responsibility for poverty among Lebanese and Portuguese university students: A cross-cultural comparison. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2002, 30, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz-Colomer, J.; Moya, M.; Valor-Segura, I. Not all poor are equal: The perpetuation of poverty through blaming those who have been poor all their lives. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 26928–26944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Xu, B.-X.; Yang, S.-L.; Guo, Y.-Y. Why are higher-class individuals less supportive of redistribution? The mediating role of attributions for rich-poor gap. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 16883–16893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Study on the Tendency of Attribution on the Gap between the Rich and the Poor in Different Social Classes; World Publishing Corporation: Guangzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss-Gal, I.; Gal, J. Poverty in the eyes of the beholder: Social workers compared to other middle-class professionals. British J. Soc. W. 2007, 37, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, B.A.; Todd, N.R. Religious and spiritual beliefs uniquely predict poverty attributions. Soc. Justice Res. 2019, 32, 459–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbio, A.; Canova, L.; Manganelli, A.M. Conservative ideology, economic conservatism, and causal attributions for poverty and wealth. Curr. Psychol. 2010, 29, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.; Cole, D.J. Causal attributions and the significance of self-efficacy in predicting solutions to poverty. Sociol. Focus 2002, 35, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canto, J.M.; Perles, F.; San Martín, J. Racismo, dominancia social y atribuciones causales de la pobreza de los inmigrantes magrebíes. Bol. Psicol. 2012, 104, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Betancor, V.; Quiles, M.N.; Morera, D.; Rodríguez, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Delgado, N.; Acosta, V. Creencias sobre las causas de la pobreza y su influencia sobre el prejuicio hacia los inmigrantes. R. Psicol. Soc. Apl. 2002, 12, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S.C.; Taef, H.; Ribeiro, R.D.M.S.; MacLachlan, M. Attributions for “Third World” poverty: Contextual factors in Australia and Brazil. Psychol. Dev. Soc. 1998, 10, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.C.; Maclachlan, M. Actors, observers, and attributions for Third World poverty: Contrasting perspectives from Malawi and Australia. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 138, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Ngok, K. Does the Dibao Program improve citizens’ life satisfaction in China? Perceptions of pathways of poverty attribution and income inequality. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 975–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojanu, S.; Stroe, C. Causes of Poverty—What do the poor think? Poverty attribution and its behavioural effects. Actas LUMEN 2017, 1, 186–197. [Google Scholar]

- Davidai, S. Why do Americans believe in economic mobility? Economic inequality, external attributions of wealth and poverty, and the belief in economic mobility. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 79, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, J.N.; Strassle, C.G.; Steck, L.W. The impact of a poverty simulation on educators’ attributions and behaviors. Clear. House J. Educ. Strateg. Issues Ideas 2019, 92, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, R.; Castillo, J.C.; Herrera, R.; Suárez, J.I. ¿Fruto del esfuerzo? Los cambios en las atribuciones sobre pobreza y riqueza en Chile entre 1996 y 2015. Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 2020, 55, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatica, L.; Navarro-Lashayas, M.A. Ideología política, actitudes hacia la inmigración y atribuciones causales sobre la pobreza en una muestra universitaria. Rev. Serv. Soc. 2019, 69, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalao, F.G. Causal attributions for poverty and their correlates. Philipp. J. Psychol. 2005, 38, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, A.M.; Macchia, L.; Whillans, A.V. The developmental origins and behavioral consequences of attributions for inequality. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussak, L.J.; Cimpian, A. An early-emerging explanatory heuristic promotes support for the status quo. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, W.E.; Oheneba-Sakyi, Y. Sociodemographic and political correlates of university students’ causal attributions for poverty. Psychol. Rep. 1993, 73, 795–800. [Google Scholar]

- Halik, M.; Malek, M.D.A.; Bahari, F.; Matshah, N.; Webley, P. Attribution of poverty among Malaysian students in the United Kingdom. Southeast Asia Psychol. J. 2012, 1, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Heaven, P.C.L. Economic locus of control beliefs and lay attributions of poverty. Aust. J. Psychol. 1989, 41, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.M.; Toft, J.E.; Garrett, K.J.; Ferguson, S.M.; Kuechler, C.F. Assessing clinical MSW students’ attitudes, attributions, and responses to poverty. J. Poverty 2016, 20, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husz, I.; Kopasz, M.; Medgyesi, M. Social workers’ causal attributions for poverty: Does the level of spatial concentration of disadvantages matter? Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 162, 1069–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, K.D.; Nekhwevha, F.H. Poverty attribution in the developing world: A critical discussion on aspects of split consciousness among low income urban slum dwellers in Lagos. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 33, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafetsios, K.; Kateri, E.; Sloam, J.; Flanagan, C.; Hayward, B.; Kalogeraki, S.; Kousis, M. Youths’ Cultural Orientations, Attributions to Inequality and Political Engagement Attitudes and Intentions. In Youth Political Participation in Greece: A Multiple Methods Perspective; Kalogeraki, S., Kousis, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2022; pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchens, S.; Ricks, L.; Hannor-Walker, T. Self-efficacy as it relates to attributions and attitudes towards poverty among school counselors-in-training. Ga. Sch. Couns. Assoc. J. 2020, 27, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Landmane, D.; Reņģe, V. Attributions for poverty, attitudes toward the poor and identification with the poor among social workers and poor people. Balt. J. Psychol. 2010, 11, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Park, C.H.K.; Rhee, S.J.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.S.; Ha, K.; Baik, C.J.; Ahn, Y.M. The influence of poverty attribution on attitudes toward suicide and suicidal thought: A cross-national comparison between South Korean, Japanese, and American populations. Compr. Psych. 2021, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubotina, O.D.; Ljubotina, D. Attributions of poverty among social work and non-social work students in Croatia. Croat. Med. J. 2007, 48, 741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McWha, I.; Carr, S.C. Images of poverty and attributions for poverty: Does higher education moderate the linkage? J. Philanthr. Market. 2009, 14, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murry, V.M.; Brody, G.H.; Brown, A.; Wisenbaker, J.; Cutrona, C.E.; Simons, R.L. Linking employment status, maternal psychological well-being, parenting, and children’s attributions about poverty in families receiving government assistance. Fam. Relat. 2002, 51, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D. Family and Community Health Study; Unpublished manuscript; University of Iowa: Des Moines, IA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser, R. Does subjective class predict the causal attribution for poverty? J. Soc. Sci. 2007, 3, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, R.; Abouchedid, K. Causal attribution of poverty among Lebanese university students. Curr. Res. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 6, 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Morçöl, G. Lay explanations for poverty in Turkey and their determinants. J. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 137, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J. Beliefs about the motivation of poor persons and attitudes toward poverty policy. Soc. Probl. 1974, 21, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, R.; Abouchedid, K. Locus of control and the attribution for poverty: Comparing Lebanese and South African university students. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2006, 34, 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, R.; Singhal, S.; Abouchedid, K. Causal attributions for poverty among Indian youth. Curr. Res. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, T.E.; Joselus, D. Cultural attributions for racial inequality. Pol. Gr. Id. 2023, 11, 876–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peffley, M.; Hurwitz, J.; Mondak, J. Racial attributions in the justice system and support for punitive crime policies. American Pol. Res. 2017, 45, 1032–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P. Stability and change in community perceptions of poverty: Evidence from Australia. J. Pov. 2003, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norcia, M.; Castellani, A.; Rissotto, A. The process of causal attribution of poverty: Preliminary results of a survey in Italy. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 1, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Norcia, M.; Rissotto, A. How does poverty work? Representations and causal attributions for poverty and wealth. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Stud. 2011, 3, 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Özpinar, Ş.; Akdede, S.H. Determinants of the attribution of poverty in Turkey: An empirical analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 164, 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, J.; Sinha, Y.; Prakash, A.; Tripathi, R.C. Right–left political ideologies and attribution of the causes of poverty. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 12, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Y.; Jain, U.; Pandey, J. Attribution of causality to poverty. J. Soc. Econ. Studies 1980, 8, 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Reutter, L.I.; Veenstra, G.; Stewart, M.J.; Raphael, D.; Love, R.; Makwarimba, E.; Mcmurray, S. Public attributions for poverty in Canada. Can. Rev. Sociol./Rev. Can. Sociol. 2006, 43, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, C.; Acosta, C.; Saavedra, B.A.; Correa, P.S. Atribuciones causales de la pobreza en ciudadano/as cordobeses. Rev. Argent. Cienc. Comport. 2018, 10, 193–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-Rodríguez, M.L.; Moreno-Jiménez, P.; Vallejo Martín, M. Atribuciones de la pobreza: Efectos en la comunidad. Psicumex 2022, 12, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, M.; García-Castro, J.D.; Jiménez-Moya, G.; Lobato, R.M. How do people understand the causes of poverty and wealth? A revised structural dimensionality of the attributions about poverty and wealth scales. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2023, 31, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segretin, M.S.; Reyna, C.; Lipina, S.J. Atribuciones sobre las causas de la pobreza general e infantil en Argentina. Interdisciplinaria 2022, 39, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolitho, F.H.; Carr, S.C.; Fletcher, R.B. Public thinking about poverty: Why it matters and how to measure it. Int. J. Nonprofit Vol. Sec. Mark. 2007, 12, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige, K.D.; Nekhwevha, F.H. Causal attributions for poverty among low income communities of Badia, Nigeria. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 38, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeffler, S.W.; Kauffman, S.E.; Joseph, R. Causal attributions of poverty among social work faculty: A regression analysis. Soc. Work Educ. 2021, 42, 1198–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; Voracek, M.; Furnham, A.; Robinson, C.; Tran, U.S. Support for weight-related anti-discrimination laws and policies: Modelling the role of attitudes toward poverty alongside weight stigma, causal attributions about weight, and prejudice. Body Image 2023, 45, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.H.; Weaver, R.D. Development and validation of a short form of the attitude toward poverty scale. Adv. Soc. Work 2010, 11, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terol-Cantero, M.C.; Martín-Aragón Gelabert, M.; Costa-López, B.; Manchón López, J.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, C. Causal attribution for poverty in young people: Sociodemographic characteristics, religious and political beliefs. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Cabrera, J.J.; Panadero Herrero, S. Pobreza en los estados menos desarrollados y sus atribuciones de causalidad: Estudio transcultural en estados latinoamericanos con diferentes niveles de desarrollo. Santiago Rev. Univ. Oriente 2007, 115, 364–379. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Cabrera, J.J.; Panadero Herrero, S. Atribuciones causales de la pobreza en los países menos desarrollados. Perfiles Latinoam. 2009, 17, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, D.W.; Montiel, C.J.; Cooksey, R.W.; Lewko, J.H. Mental models of poverty in developing nations: A causal mapping analysis using a Canada-Philippines contrast. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 2005, 36, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchis Carrillo, D.E. Pobreza, desigualdad y religión: Creencias religiosas y atribuciones causales de la pobreza en México. Rev. Temas Sociol. 2022, 30, 253–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss-Gal, I.; Gal, J. Israel. In Professional Ideologies and Preferences in Social Work: A Global Study; Weiss-Gal, I., Gal, J., Dixon, J., Eds.; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 2003; pp. 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Wollie, C.W. Causal attributions for poverty among youths in Bahir Dar, Amhara region, Ethiopia. J. Soc. Evol. Cult. Psychol. 2009, 3, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, S.A.; Ernest, K. Attributions for poverty: A survey of student’s perception. Int. Rev. Manag. Market. 2012, 2, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gatica, L.; Martini, J.P.; Dreizik, M.; Imhoff, D. Psychosocial and psycho-political predictors of social inequality justification. R. Psicol. 2017, 35, 279–310. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bastias, F.; Peter, N.; Goldstein, A.; Sánchez-Montañez, S.; Rohmann, A.; Landmann, H. Measuring Attributions 50 Years on: From within-Country Poverty to Global Inequality. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030186

Bastias F, Peter N, Goldstein A, Sánchez-Montañez S, Rohmann A, Landmann H. Measuring Attributions 50 Years on: From within-Country Poverty to Global Inequality. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(3):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030186

Chicago/Turabian StyleBastias, Franco, Nadja Peter, Aristobulo Goldstein, Santiago Sánchez-Montañez, Anette Rohmann, and Helen Landmann. 2024. "Measuring Attributions 50 Years on: From within-Country Poverty to Global Inequality" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 3: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030186

APA StyleBastias, F., Peter, N., Goldstein, A., Sánchez-Montañez, S., Rohmann, A., & Landmann, H. (2024). Measuring Attributions 50 Years on: From within-Country Poverty to Global Inequality. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14030186