Abstract

Passive psychoeducation is an easily accessible and cost-effective self-guided intervention that does not use elements of active psychotherapies or require homework. The present study aimed to investigate the acceptability and efficacy of a 7-week app-based passive psychoeducation stress management program to promote adaptive emotion regulation and coping skills in university students (i.e., 80% psychology students). Participants were tested via Lime-Survey® at pre- and post-test with the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), the Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ), and the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ). A stratified permutation block randomization by age, gender, and the DASS-21 stress subscale was performed. Each week, the psychoeducation group (n = 123) received different psychoeducation modules. At the end of each module, participants answered questions about their satisfaction with each module and adherence to psychoeducation. The control group (n = 130) received no intervention. The psychoeducation program led to a significant improvement in the adaptive emotion regulation strategy: “reappraisal” (p = 0.004) and a significant reduction in the dysfunctional coping style: “symptom-related rumination” (p = 0.01) but not to a significant reduction in depression, anxiety, and stress scores compared to the control group. Thus, the present study might demonstrate a preventive effect of an app-based passive psychoeducation program in students with low clinically relevant psychopathological symptoms.

1. Introduction

Stress is an important risk factor for mental and physical health [1,2]. A wealth of empirical evidence suggests that stress increases the likelihood of developing mental illness, particularly depression, and also increases mortality rates, such as suicide [3]. Students in particular are exposed to a variety of stressors. Academic stressors include regular performance reviews, work overload, competitiveness, and worries about the future. Non-academic stressors such as leaving the familiar living environment, finding one’s identity, adapting to a new social environment, and financial stress also play an important role [4,5]. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, studies showed that students experienced an increased level of stress [6,7,8,9]. Furthermore, the prevalence of mental illnesses among university students, particularly depression and anxiety disorders, increased from 22% to 36% between 2007 and 2017 [10]. In addition to the pre-existing stressors that affect students, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic brought additional stress factors. One such factor was the lack of social contact due to e-learning, which has led to increased anxiety and stress, concentration problems, as well as depressive symptoms and sleep problems [11,12,13,14,15].

Despite the high prevalence of mental illness among university students, approximately two-thirds do not receive adequate psychological help [16,17]. Furthermore, untreated mental health problems among students have a significant negative impact on their quality of life and increase the risk of dropping out of university [18,19,20]. Therefore, the need for easily accessible psychological therapies to help students cope with stress and promote their mental health is significant [21]. In conjunction with establishing therapeutic support services, the implementation of preventative measures that promote students’ stress management and resilience skills should be a top priority for higher education institutions. Preventive stress management is described as an intervention that provides didactic knowledge, including information about stressors, coping strategies, and their application before stressful scenarios occur. In this way, certain behaviors and maladaptive thinking patterns can be improved [22].

According to Romano [23], stress management programs should include three elements. First, objective information about stress and the associated physiological response should be provided. Therefore, it is important to introduce stress modulation techniques, including breathing techniques. Second, because of the various stressors students are exposed to, knowledge of dysfunctional thoughts, emotion regulation, and coping skills plays an important role in psychoeducational stress management programs. These skills have a mediating effect on the health consequences associated with stress [24,25]. The goal is to raise students’ awareness of the role of dysfunctional thinking in the development and maintenance of stress. In addition, students should be introduced to the primary methods of emotion regulation (cognitive reappraisal and expressive emotional suppression) and encouraged to reflect on their own coping behaviors. The third aspect of psychoeducation for stress management focuses on lifestyle habits, especially on raising awareness of healthy and unhealthy habits and educating individuals about the importance of sleep, nutrition, and physical activity.

Today, psychoeducation is an essential component of a comprehensive treatment approach for all mental illnesses. It includes the teaching of disorder-specific information and priorities in both a curative and preventive context. Psychoeducation is based on the principle that knowledge about mental illness and its causes and effects can influence people’s behavior, particularly when they are confronted with stressors [26]. In academic research, a distinction is made between active and passive psychoeducation programs.

On the one hand, active psychoeducation programs refer to a therapeutic setting with guidance and specific interventions, such as those found in group therapy [27]. Numerous studies suggest that active psychoeducation programs are effective in treating a variety of mental disorders, including anxiety disorders, depression, or chronic pain disorders, but can also reduce caregivers’ burden (for a meta-analysis, see [27,28,29,30,31]). In addition, previous research has shown that active psychoeducational stress management training is also a successful intervention for university students to reduce stress, depression, and other psychological symptoms, although the effect size is rather small (e.g., meta-analyses and reviews by [32,33]).

Passive psychoeducation, on the other hand, is an easily accessible and cost-effective intervention that disseminates information via flyers, the internet, and personal contacts, without using elements of active psychotherapies (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT]) or requiring homework such as relaxation exercises that participants perform at home. A meta-analysis of passive psychoeducational interventions showed a small effect on depressive and psychological distress symptoms [27].

Internet-based forms of psychoeducation and stress management programs are particularly suitable for younger generations, such as students, who have a firm grasp on digital technologies. App-based stress-management programs offer easy and anonymous access, combined with cost-effectiveness, economy, and flexibility [34,35,36]. Previous meta-analyses have summarized the effectiveness of internet interventions for a variety of mental disorders (e.g., [36,37,38,39]). As a result, increasing attention has been paid to the prevention of mental disorders in recent years. Numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses summarize the effectiveness of a variety of internet-based psychological and psychoeducational interventions in the prevention of various mental disorders (for an overview and meta-analysis, see [40,41,42]). Nevertheless, only a few studies examined the effectiveness of internet-based preventive interventions to promote and develop strength and resilience in younger people with less severe psychopathological symptoms [43,44,45,46,47].

So far, Donker et al., [27] have shown that passive psychoeducation programs have a small effect on depressive and psychological stress symptoms, but evidence for the effectiveness of passive psychoeducation as a preventive measure is lacking. Internet-based passive psychoeducational interventions are relatively easy to implement and can be applied immediately to a large population. They could be a good first step for subclinical populations by overcoming traditional barriers to seeking help for stress, but can also be used as prevention and promotion strategies for mental health at colleges and universities.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the acceptability and effectiveness of a 7-week app-based passive psychoeducational stress management program to promote adaptive emotion regulation and coping skills in an unselected group of university students. We hypothesized that the 7-week app-based passive psychoeducational stress management program would improve students’ adaptive emotion regulation strategies and reduce maladaptive strategies such as “rumination”, “distraction”, and “suppression” compared to the waiting list control group. Additionally, we expected beneficial effects of the 7-week app-based passive psychoeducational stress management program on symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression compared to the waiting list control group.

2. Materials and Methods

Students at the University of Innsbruck (Austria) were recruited via the university’s official student mailing list (for all courses at the university), social media, and in psychology classes. Bachelor students of psychology received course credit for participation in this study. Data were collected at two timepoints (May 2022 and October 2022). Participation in this study was voluntary and informed consent was obtained from all students prior to participation. This study was in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the University of Innsbruck (No. 26/2022).

The present randomized controlled parallel-group study comprised 294 participants [226 female, 65 male, and 3 gender non-conforming/questioning/other students; mean age: 22.4 years (standard deviation: 3.6)]. In the course of this study, n = 41 participants were excluded from the data analyses because they discontinued the study or did not complete all questionnaires. Thus, the data of 253 students (194 female, 57 male, and 2 gender non-conforming/questioning/other students) were finally subjected to data analyses (123 from the psychoeducation group and 130 from the waiting list control group).

2.1. Measurements

2.1.1. Mental Health

Mental health was assessed using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) [48,49]. The DASS-21 is a self-report screening instrument consisting of three subscales with 7 items that assess symptoms of depression (e.g., “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feelings at all”), anxiety (e.g., “I was aware of dryness of my mouth”), and stress (e.g., “I found myself getting agitated”) in the past week. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“never”) to 3 (“almost always”), with the total score for each subscale ranging from 0 to 21. The three subscales have good psychometric properties, including internal consistency and validity [50]. The convergent and discriminant validity of the DASS-21 are sufficient [50].

2.1.2. Coping Style

The German short version of the Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ-D) [51] was developed to measure coping styles according to the response styles theory [52]. It is a 23-item scale containing three subscales: symptom-focused rumination (7 items, e.g., “When I feel sad or depressed, I go away by myself and think about why I feel this way”), self-focused rumination (8 items, e.g., “When I feel sad or depressed, I think I won’t be able to do my job/work because I feel so badly”) and distraction (8 items, e.g., “When I feel sad or depressed, I help someone else with something in order to distract myself”). The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“almost never”) to 4 (“almost always”). There is evidence of sufficient psychometric properties for clinical and non-clinical patients [51].

2.1.3. Emotion Regulation

To assess how emotions are regulated or controlled, we used the German version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) [53]. The ERQ consists of 10 items that assess the habitual use of two emotion regulation strategies, namely cognitive reappraisal (6 items) and expressive suppression (4 items). Cognitive reappraisal refers to the ability to change the way someone thinks about potentially emotion-triggering events. This occurs at an early stage of emotional processing (e.g., “When I am faced with a stressful situation, I will make myself think about it in a way that makes me stay calm”). Habitual suppression of emotional expression is the tendency not to show one’s emotions (e.g., “When I am feeling negative emotion, I make sure not to express them”). The items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores on the subscales indicate greater engagement in this strategy. The internal reliability is considerable, where Cronbach’s alpha is 0.73 for suppression and 0.79 for reappraisal [54].

2.1.4. Questionnaire about Satisfaction with Each Module and Adherence to Psychoeducation

After each module, we collected participants’ feedback on satisfaction with the individual modules using the following two questions: 1. How helpful did you find the information material this week? 2. How well informed did you feel about the topic? The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 4 (“very good”) to 1 (“very bad”).

To explore user engagement and adherence to the app-based passive psychoeducational stress management program, we used the following two questions:

1. Were you able to apply the knowledge you learned in the psychoeducation in everyday life during the last week? 2. Did you feel relieved by using the psychoeducation?

Again, the items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 4 (“regularly” = more than 5 days a week) to 1 (“never”).

For the analysis, we used the mean value of the questions across the modules.

Finally, we asked open-ended questions about additional features that the participants would like to see included in the next iteration.

2.2. Procedure

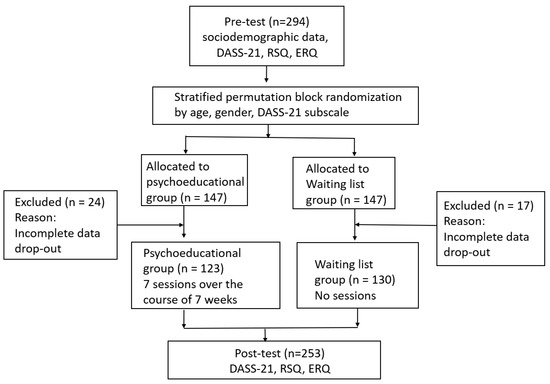

For an overview of the entire study procedure, including the questionnaires used, see Figure 1. The mean values and standard deviations of all study variables are given in the Section 3.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the present study.

Information on self-reported socio-demographic data was collected at the beginning of this study using a web-based questionnaire. During the 7-week study period, each participant was tested twice, at pre- and post-test, with the following questionnaires: DASS-21, RSQ, ERQ. Psychometric assessment took place online via Lime-Survey®. After the pre-test, a stratified permutation block randomization was performed. In a two-stage procedure, all subjects were first grouped into strata (age, gender, and subscale stress score of the DASS-21 at pre-test). In the second step, subjects were assigned to the psychoeducation group (n = 147) or the waiting list group (n = 147) using block randomization. Over a period of seven weeks, participants in the psychoeducation group received different psychoeducation modules and a push notification on their smartphone every Monday. The order of the modules was fixed and could not be chosen individually by the students (see Table 1). The psychoeducational program was implemented with the software “Quenza App server v. 1.0.0 (Maastricht, The Netherlands)” (https://quenza.com) and all participants used the software via their smartphones. The program comprised seven modules: (week 1) Stress, (week 2) Daily routine, (week 3) Emotion regulation and problem solving, (week 4) Sleep, (week 5) Pleasurable activities, (week 6) Physical activity, and (week 7) Nutrition. Further details on the different modules of the psychoeducational stress management program can be found in Table 1. Each module took approximately 10 to 15 min to complete, but participants in the intervention group were allowed to view the entire content of the modules as many times and for as long as they wished. Researchers monitored each participant’s detailed login information in the backend system and reminded participants via text message to log in and complete the modules. After each module on Friday, we collected satisfaction feedback from the participants and asked open-ended questions about additional features they would like to see in the next iteration. The control group received no intervention but was informed that they would receive access to the full psychoeducation material after the post-test.

Table 1.

Details about the seven modules of the psychoeducational stress management program.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

In the course of this study, n = 41 participants (n = 24 in the psychoeducation group; n = 17 in the waiting group) were excluded from the data analyses because they discontinued the study or did not complete all questionnaires. Thus, the data of 253 study participants were subjected to data analysis.

Descriptive statistics are presented as means and standard deviations (mean ± SD). To compare demographic variables (age, gender, the number of psychology students per group, psychotherapeutic treatment and mental illness) between the two groups, either a t-test, chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test were performed. Multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were performed to examine baseline group differences in the questionnaires, using the questionnaire scores as dependent variables.

A two-way mixed multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to examine the questionnaire responses, using the between-subjects factor “group” (psychoeducation vs. waiting group) and the within-subjects factor “time” (pre-test vs. post-test treatment week). The group x time interaction was of particular interest as it could reveal the effects of the psychoeducation intervention on the parameters studied. Significant group x time interactions were examined by pairwise post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction. We tested for homogeneity of variances in the between-subjects factor using Box’s M test. Furthermore, we examined skewness and kurtosis to test for deviations from normal distribution in the dependent variables. Unless otherwise stated in the Section 3, we confirm that all these assumptions were met. For significant effects, we report partial eta-squared effect sizes. All analyses were conducted with a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed).

3. Results

The age range of the sample was between 18 and 36 years (mean age: M = 22.24 ± 3.23). A total of 194 female, 57 male, and 2 gender-diverse students participated in this study. Of the participants, 86.6% (n = 219) were undergraduate students, while 12.2% (n = 31) were enrolled in a master’s program and 1.2% (n = 3) were students in a PhD program. Most students (80.2%) were studying psychology (n = 203).

Regarding mental health, 46 participants (18.2%) reported that they were currently suffering from a mental illness and undergoing psychotherapeutic or psychiatric treatment, and 20.5% (n = 52) reported about a history of mental illness and previous psychotherapeutic or psychiatric treatment.

Sociodemographic and study-related information for both groups is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and study-related information.

At baseline, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the variables age (t (251) = −0.94, p = 0.35), gender (Fisher’s exact tests with Monte Carlo estimation: p = 0.61), the number of psychology students per group (χ2 (1) = 1.36, p = 0.24), as well as psychotherapeutic treatment (χ2 (1) = 2.05, p = 0.15) and mental illness (χ2 (1) = 0.53, p = 0.46).

Based on three separate MANOVAs, there were no significant differences between the psychoeducation group and the waiting list group at baseline in the DASS-21 scales (F(3249) = 5.87, p = 0.64, ηp2 = 0.01), the RSQ-D scales (F(3249) = 2.31, p = 0.08, ηp2 = 0.03), and the ERQ scales (F(2250) = 0.01, p = 0.99, ηp2 < 0.001). The means and standard deviations of the pre-test variables are shown together with the post-test statistics in Table 3.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations of pre-test variables.

3.1. Mental Health

A multivariate mixed analysis of variance (MANOVA) for the three DASS-21 scales, i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress, showed no significant group x time interaction effect (F(3249) = 0.45, p = 0.72, ηp2 = 0.01) and no main effect of group (F(3249) = 0.33, p = 0.80, ηp2 = 0.004), but a significant main effect of time (F(3249) = 5.88, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07). Post hoc tests showed a significant decrease in both groups only in the DASS anxiety score between the pre- and post-tests (F(1251) = 16.56, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06), but not for the depression (F(1251) = 0.94, p = 0.33, ηp2 = 0.004) and stress (F(1251) = 1.11, p = 0.29, ηp2 = 0.004) subscales.

3.2. Coping Style

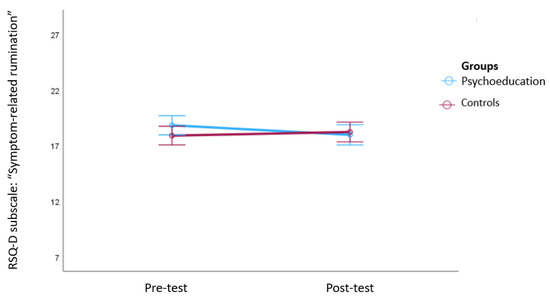

A multivariate mixed analysis of variance (MANOVA) for the three subscales of the RSQ-D (i.e., symptom-related rumination, self-related rumination, and distraction) revealed a significant interaction of group x time (F(3249) = 2.83, p = 0.039, ηp2 = 0.03) and a significant main effect of time (F(3249) = 22.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.21). The main effect of group was not significant (F(3249) = 0.99, p = 0.40, ηp2 = 0.01). Post hoc tests showed a significant decrease in the “symptom-related rumination” subscale from the pre- to the post-test phase only for the psychoeducation group, while the waiting list control group showed an increase (F(1251) = 6.46, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.03). See Figure 2 for an illustration of this effect. No significant group x time interactions were found for the “self-related rumination” (F(1251) = 0.33, p = 0.56, ηp2 = 0.001) and “distraction” (F(1251) = 0.02, p = 0.88, ηp2 < 0.001) subscales.

Figure 2.

Changes in the RSQ-D subscale “symptom-related rumination” between pre- and post-test. Note: The figure shows means and 95% confidence intervals of the means. A significant decrease in symptom-related rumination only occurred in the psychoeducation group, while the waiting list control group showed an increase.

However, both groups showed a significant decrease in the coping strategy: “self-related rumination” (F(1251) = 4.22, p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.02) and an increase in the subscale: “distraction” (F(1251) = 62.78, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.20) between the pre- and post-test.

3.3. Emotion Regulation

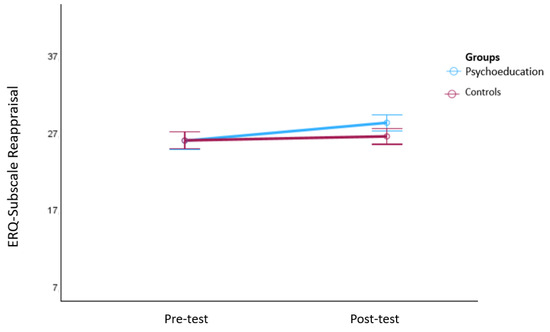

Finally, a multivariate mixed analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted for the “reappraisal” and “suppression” ERQ subscales. The analyses showed a significant group x time interaction (F(2250) = 5.08, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.04) and a significant main effect of time (F(2250) = 10.45, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08) but no significant main effect of group (F(2250) = 0.89, p = 0.41, ηp2 = 0.01). Post hoc tests revealed a significant increase in the “reappraisal” subscale from the pre- to the post-test phase only in the psychoeducation group (F(1251) = 8.36, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.03). See Figure 3 for an illustration of this effect. No significant effects were found for the “suppression” ERQ subscale (group x time interaction (F(1251) = 1.59, p = 0.21, ηp2 = 0.01) and main effect of time (F(1251) = 0.02, p = 0.88, ηp2 < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Changes in the ERQ subscale “reappraisal” from the pre- to the post-test phase. Note: The figure shows means and 95% confidence intervals of the means. Significant increases in the subscale: “reappraisal” were only observed in the psychoeducation group.

3.4. Satisfaction with and Adherence to the Passive Psychoeducation Program

The three most important topics mentioned by the students were daily structure, stress and regeneration, and sleep. For future adaptations of the program, it was recommended to address topics specific to the target group of students, such as exam anxiety.

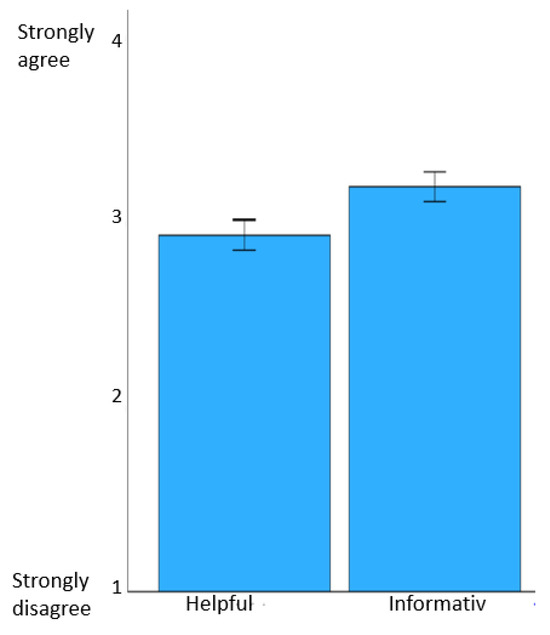

As indicators of acceptability, a questionnaire was used to collect information on satisfaction with the intervention and ratings of the program’s usefulness. Across all modules, students found the modules very helpful (mean ± SD = 2.93 ± 0.46) and they felt well informed about the individual topics (mean ± SD = 3.19 ± 0.45).

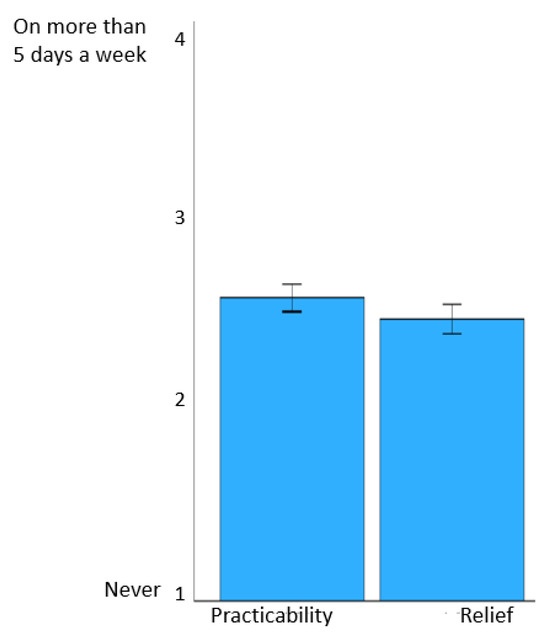

On average, they were also able to apply the knowledge they had learned in everyday life on half of the days of the week (mean ± SD = 2.65 ± 0.42) and felt relieved by the use of psychoeducation (mean ± SD = 2.53 ± 0.44). The results with regard to satisfaction with and engagement in/adherence to the program are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Satisfaction with the modules. Note: the figure shows mean values of questions across the modules and 95% confidence intervals of the means.

Figure 5.

Engagement in and adherence to the psychoeducation program. Note: the figure shows the mean values of questions across the modules and 95% confidence intervals of the means.

4. Discussion

In the present study, a seven-week app-based passive psychoeducation program led to significant improvement in the “reappraisal” adaptive emotion regulation strategy and a significant reduction in the “symptom-related rumination” dysfunctional coping style compared to a waiting list control group. However, the psychoeducation program showed no significant effects on other maladaptive strategies, such as “self-focused rumination”, “distraction”, and “suppression”, compared to the waiting list control group.

Previous studies with active psychoeducation programs in “face-to-face” settings have shown similar results, demonstrating a significant improvement in adaptive coping styles and a reduction in various maladaptive coping styles [32,55,56,57]. However, it is important to keep in mind that most active psychoeducation programs had a specific focus on training adaptive coping strategies during the courses.

In addition, studies using internet-based active stress management training also showed a positive effect on individual emotion regulation strategies [58,59,60,61,62]. Most internet-based active stress management courses offered additional online support from a trained e-coach to increase adherence to and the effectiveness of the intervention [63,64]. The extent of therapeutic support varied both in form (written support via e-mail, video consultations, additional group sessions, etc.) and in scope (between 1 and 14 h) between the individual studies. Even though internet-based programs for active stress management require significantly fewer resources than face-to-face interventions, they are still associated with increased time and financial expenditure.

In the current study, we were able to show that even a passive psychoeducation program, which is very time- and cost-effective, leads to a significant improvement in adaptive emotion regulation strategies and a significant reduction in dysfunctional coping styles compared to a waiting list control group.

Despite the improvement in adaptive emotion regulation and coping skills, the seven-week app-based passive psychoeducation program did not result in a significant reduction in depression, stress, and anxiety scores compared to the waiting list group. This is not surprising as the sample scores for all three scales were in a low, non-clinically relevant range at the start of this study. Additionally, these results are probably attributable to the lack of integration of psychological support sessions aimed at resolving emotional difficulties according to targeted treatments. Previous meta-analyses have shown that psychoeducation programs for stress management with active interventions (e.g., mindfulness-based interventions, CBT), either delivered in face-to-face group settings or internet-based, are an effective intervention for students to reduce stress, depressed mood, or other psychological distress (e.g., meta-analyses and reviews in [32,33]). Similarly, the meta-analysis in [27] showed that passive psychoeducation programs also have a small effect on depression and stress symptoms. However, these studies often selected samples with elevated psychopathological scores at the start of the program. In addition, different methodological approaches, such as focusing psychoeducational content on certain symptoms, such as anxiety symptoms, contribute to heterogeneous study results.

5. Limitations

Pre–post studies carry the risk of bias, especially in a university setting. It can be assumed that students have different levels of stress at the beginning of their studies, at the beginning of the semester, or during the examination period. Additionally, there is an ongoing debate regarding the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of these programs (see, e.g., [42,65]). Therefore, a follow-up measurement after a period of several months would be necessary to confirm a long-term preventive effect of the 7-week app-based passive psychoeducation program.

Furthermore, a direct comparison with other studies is difficult as the studies differ greatly in terms of student population, duration of intervention, content of psychoeducation, and questionnaires used. The current study consisted mainly of psychology students. This may limit the generalizability of our results, as the stress experience and coping mechanisms of psychology students may not be representative of the general population, as psychology students may have more knowledge about mental health and stress-coping techniques than the average population. Consistent with this reasoning, psychology students in the present study tended to report less stress and fewer mental health problems than students in other programs. In addition, the gender ratio was not balanced across the sample, as the majority of the students (76.7%) were female. The literature about the mental health of students from different academic disciplines is heterogeneous and several factors may account for inconsistent study results, such as the female ratio in the study population as well as demographic factors (e.g., age, socioeconomic status, geographical location, or cultural influence) and a wide variety of course structures (see, e.g., [66,67]).

Internet-based interventions have numerous advantages, such as cost-effectiveness as well as high accessibility, convenience, and flexibility of use at any time and place compared to traditional in-person interventions. At the same time, however, high flexibility in terms of time and location can increase the susceptibility to various confounding variables that may influence the use of the program and completion of the questionnaire. It is important to keep in mind that in the current study, we had no control over whether the study participants actually read the psychoeducation material carefully. However, as an indicator for user engagement and adherence to the psychoeducational modules, we collected participants’ feedback on how often they were able to apply the knowledge they had learned in everyday life and whether they felt relieved by the use of psychoeducation. On average, on half of the days of the week, the students applied their knowledge and felt relieved by the use of the psychoeducation program.

6. Implications for Practice and Research

Psychological counseling centers at universities offer low-threshold help for students [68], and a recent systematic review confirmed the effectiveness of face-to-face and online counseling interventions in improving the mental health of university students [69]. A meta-analysis by Osborn and Saunders [70] showed that a good proportion of students use these services, but some barriers still exist, such as low help-seeking behavior and fear of stigmatization, low mental health literacy, or misconceptions about and lack of trust in counselors [69]. Because of the high prevalence of mental health disorders in students, there is an urgent need to expand these services. Web-based or app-based programs, especially, offer the opportunity to provide large-scale psychological support. In practice, passive app- or internet-based psychoeducation programs could be used as a low-threshold component in multi-level counseling concepts in the college environment. First-year students, in particular, are exposed to various stressors, such as coping with new academic demands and external pressure from family, teachers, and society, as well as the need to constantly adapt to new situations. In order to promote stress management skills early on and increase resilience, our passive psychoeducation program could be used in freshman courses. Low-threshold passive psychoeducation programs are particularly relevant to students who are reluctant to use other forms of treatment, as this program offers anonymity, flexibility, easy and constant digital availability, and is cost-effective.

This study highlights the need for further research, particularly the inclusion of broader and more diverse samples, especially those with elevated psychopathology scores. It would also be beneficial to conduct follow-up measurements to investigate and improve the short- and long-term effectiveness of the psychoeducation program. The addition of more applied content that can be individually selected by students, such as psychoeducation on psychological problems like depression, anxiety, and substance abuse, as well as the implementation of audiovisual or interactive components such as quizzes and case vignettes could increase the effectiveness of the psychoeducation program.

7. Conclusions

Effective stress management through the increased use of adaptive coping strategies is considered a preventive factor that can protect against stress-related illness, unhealthy behavior in response to stress, and the long-term physical and psychological effects of stress (see meta-analyses in [71,72]). Thus, in the present study, the preventive effect of an internet-based passive psychoeducation program on students with low clinically relevant psychopathological symptoms was demonstrated. As the program did not include specific interventions such as mindfulness or CBT exercises, it was also very time- and cost-efficient for the students. This was also reflected in the high level of acceptance of the program. Psychological counseling centers at universities offer low-threshold help for students [68], but only some of the help needed is utilized. In practice, passive app- or internet-based psychoeducation programs could be implemented as a low-threshold component in multi-level counseling concepts in university settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.W. and M.C.; methodology, E.M.W., S.S., B.H., G.R., V.D. and M.C.; formal analysis, E.M.W.; investigation, E.M.W.; data curation, E.M.W., M.C. and V.D., writing—original draft preparation, E.M.W., M.C. and V.D.; writing—review and editing, E.M.W., S.S., B.H., G.R., V.D. and M.C.; project administration, E.M.W.; funding acquisition, E.M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency, grant number 880557 (Care4Stress).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the University of Innsbruck, Austria (No. 26/2022). Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation. Data confidentiality was guaranteed and the participants were informed that they had the right to withdraw from this study at any time.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Linda Bühner and Liliane Sigmund for their valuable help in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Klein, E.M.; Brähler, E.; Dreier, M.; Reinecke, L.; Müller, K.W.; Schmutzer, G.; Wölfling, K.; Beutel, M.E. The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale–Psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämmig, O.; Bauer, G. Work-life imbalance and mental health among male and female employees in Switzerland. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfino, J.P.; Barragán, E.; Botella, C.; Braun, S.; Bridler, R.; Camussi, E.; Chafrat, V.; Lott, P.; Mohr, C.; Moragrega, I.; et al. Quantifying insufficient coping behavior under chronic stress: A cross-cultural study of 1303 students from Italy, Spain and Argentina. Psychopathology 2015, 48, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozos-Radillo, B.E.; de Lourdes Preciado-Serrano, M.; Acosta-Fernández, M.; de los Ángeles Aguilera-Velasco, M.; Delgado-García, D.D. Academic stress as a predictor of chronic stress in university students. Psicol. Educ. 2014, 20, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiter, R.; Nash, R.; McCrady, M.; Rhoades, D.; Linscomb, M.; Clarahan, M.; Sammut, S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J. Affect. Dis. 2015, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, T.R.; Dlugosch, G.E. Stress im Studium. Prävent. Gesundheitsförd. 2013, 8, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grützmacher, J.; Gusy, B.; Lesener, T.; Sudheimer, S.; Willige, J. Gesundheit Studierender in Deutschland 2017. Ein Kooperationsprojekt Zwischen dem Deutschen Zentrum für Hochschul-und Wissenschaftsforschung, der Freien Universität Berlin und der Techniker-Krankenkasse; Techniker Krankenkasse: Hamburg, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.tk.de/resource/blob/2050660/8bd39eab37ee133a2ec47e55e544abe7/gesundheit-studierender-in-deutschland2017-studienband-data.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Herbst, U.; Voeth, M.; Eidhoff, A.T.; Müller, M.; Stief, S. Studierendenstress in Deutschland–Eine Empirische Untersuchung; AOK-Bundesverband: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://www.uni-heidelberg.de/md/journal/2016/10/08_projektbericht_stressstudie.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Lipson, S.K.; Lattie, E.G.; Eisenberg, D. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. College students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, C.; Schmidt, M.H.; Cajochen, C. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on human sleep and rest-activity rhythms. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R795–R797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.J.; Ji, Y.; Li, Y.H.; Pan, H.F.; Su, P.Y. Prevalence of anxiety symptom and depressive symptom among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A metaanalysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Wang, J.; Ou-Yang, X.Y.; Miao, Q.; Chen, R.; Liang, F.X.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Tang, Q.; Wang, T. The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status. Sleep Med. 2020, 77, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patelarou, A.; Mechili, E.A.; Galanis, P.; Zografakis-Sfakianakis, M.; Konstantinidis, T.; Saliaj, A.; Bucaj, J.; Alushi, E.; Carmona-Torres, J.M.; Cobo-Cuenca, A.I.; et al. Nursing students, mental health status during COVID-19 quarantine: Evidence from three European countries. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, C.; Hegde, S.; Smith, A.; Wang, X.; Sasangohar, F. Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, R.; Pitman, E.; Sharpington, A.; Stock, M.; Cage, E. Student perspectives on mental health support and services in the UK. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2020, 44, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, M.; Apolinário-Hagen, J.; Fritsche, L.; Salewski, C.; Zarski, A.C.; Lehr, D.; Baumeister, H.; Cuijpers, P.; Ebert, D.D. Effect of an internet- and app-based stress intervention compared to online psychoeducation in university students with depressive symptoms: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 2021, 24, 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruffaerts, R.; Mortier, P.; Auerbach, R.P.; Alonso, J.; De la Torre, A.E.H.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hasking, P.; et al. Lifetime and 12-month treatment for mental disorders and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among first year college students. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 28, e1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Granada-López, J.M.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Pellicer-García, B.; Antón-Solanas, I. The Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Stress and Their Associated Factors in College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorley, C. Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities; Institute for Public Policy Research: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amanvermez, Y.; Zhao, R.; Cuijpers, P.; de Wit, L.M.; Ebert, D.D.; Kessler, R.C.; Bruffaerts, R.; Karyotaki, E. Effects of self-guided stress management interventions in college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Internet Interv. 2022, 28, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/preventive-stress-managent (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Romano, J.L. Psychoeducational Interventions for Stress Management and Well-Being. J. Couns. Dev. 1992, 71, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Lai, H.L.; Lu, Y.C.; Chen, W.K.; Chi, S.C.; Lu, C.Y.; Chen, C.I. Risk Factors and Coping Style Affect Health Outcomes in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2016, 18, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkasavage, E.; Arigo, D.; Schumacher, L.M. Social comparison, negative body image, and disordered eating behavior: The moderating role of coping style. Eat. Behav. 2015, 16, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günaydin, N. Effect of group psychoeducation on depression, anxiety, stress and coping with stress of nursing students: A randomized controlled study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donker, T.; Griffiths, K.M.; Cuijpers, P.; Christensen, H. Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2009, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baourda, V.C.; Brouzos, A.; Mavridis, D.; Vassilopoulos, S.P.; Vatkali, E.; Boumpouli, C. Group Psychoeducation for Anxiety Symptoms in Youth: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Spec. Group Work. 2021, 47, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Xu, B.; Ng, M.S.N.; Duan, Y.; So, W.K.W. Effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions among caregivers of patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 127, 104162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okafor, A.J.; Monahan, M. Effectiveness of Psychoeducation on Burden among Family Caregivers of Adults with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2023, 2023, 2167096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Ullah, S.; Meyer, C.; Wang, J.; Pot, A.M.; Shifaza, F. The Experiences of Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia in Web-Based Psychoeducation Programs: Systematic Review and Metasynthesis. JMIR Aging 2023, 6, e47152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.H.B.; Meriç, M.; Ayasrah, M. The Effect of Psychoeducational Stress Management Interventions on Students Stress Reduction: Systematic Review. J. Educ. Cult. Psychol. Stud. 2022, 25, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Van Daele, T.; Welzijn, S.; En Gezin, V.; Hermans, D.; Van Audenhove, C.; Van Den Bergh, O. Stress Reduction through Psychoeducation: A Meta-Analytic Review. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Meriç, M. The effect of an online psychoeducational stress management program on international students’ ability to cope and adapt. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 1673–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, M.; Adam, S.H.; Fleischmann, R.J.; Baumeister, H.; Auerbach, R.; Bruffaerts, R.; Cuijpers, P.; Kessler, R.C.; Berking, M.; Lehr, D.; et al. Effectiveness of an internet- and app-based intervention for college students with elevated stress: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrer, M.; Adam, S.H.; Baumeister, H.; Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Auerbach, R.P.; Kessler, R.C.; Bruffaerts, R.; Berking, M.; Ebert, D.D. Internet interventions for mental health in university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 28, e1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Cuijpers, P.; Craske, M.G.; McEvoy, P.; Titov, N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, C.; Mira, A.; Herrero, R.; García Palacios, A.; Baños, R.M. Un programa de intervención autoaplicado a través de Internet para el tratamiento de la depresión: “Sonreír es divertido”. Aloma Rev. Psicol. 2015, 33, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Marín, J.; Araya, R.; Pérez-Yus, M.C.; Mayoral, F.; Gili, M.; Botella, C.; Baños, R.; Castro, A.; Romero-Sanchiz, P.; López-Del-Hoyo, Y.; et al. An internet-based intervention for depression in primary Care in Spain: A randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heber, E.; Ebert, D.D.; Lehr, D.; Cuijpers, P.; Berking, M.; Nobis, S.; Riper, H. The benefit of web- and computer-based interventions for stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennemann, S.; Beutel, M.E.; Zwerenz, R. Drivers and barriers to acceptance of web-based aftercare of patients in inpatient routine care: A cross-sectional survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, L.; Rausch, L.; Baumeister, H. Effectiveness of internet-based interventions for the prevention of mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Ment. Health 2016, 3, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.A.M.; Klein, B.; Ciechomski, L. Best practices in online therapy. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2008, 26, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, R.M.; Etchemendy, E.; Mira, A.; Riva, G.; Gaggioli, A.; Botella, C. Online positive interventions to promote well-being and resilience in the adolescent population: A narrative review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolier, L.; Haverman, M.; Westerhof, G.J.; Riper, H.; Smit, F.; Bohlmeijer, E. Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lintvedt, O.K.; Griffiths, K.M.; Sorensen, K.; Ostvik, A.R.; Wang, C.E.A.; Eisemann, M.; Waterloo, K. Evaluating the effectiveness and efficacy of unguided internet-based self-help intervention for the prevention of depression: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2013, 20, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, R.D.; Buckey, J.C.; Zbozinek, T.D.; Motivala, S.J.; Glenn, D.E.; Cartreine, J.A.; Craske, M.G. A randomized controlled trial of a self-guided, multimedia, stress management and resilience training program. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS–21, DASS–42); APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nilges, P.; Essau, C. DASS. Depressions-Angst-Stress-Skalen-Deutschsprachige Kurzfassung; ZPID, Leibniz-Institut für Psychologie Open Test Archive: Trier, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühner, C.; Huffziger, S.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. RSQ-D Response Styles Questionnaire–Deutsche Version; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991, 100, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abler, B.; Kessler, H. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire–Eine deutschsprachige Fassung des ERQ von Gross und John. Diagnostica 2009, 55, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, C.; Morgan, M. Evaluation of a Psychoeducational Program to Help Adolescents Cope. J. Youth Adolesc. 2005, 34, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Trace, A.; O’Donovan, M.; O’Regan, P.; Brady-Nevin, C.; O’Shea, M.; Martin, A.M.; Murphy, M. Coping with stressful events: A pre-post-test of a psychoeducational intervention for undergraduate nursing and midwifery students. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 61, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, M.; Dolbier, C. Evaluation of a Resilience Intervention to Enhance Coping Strategies and Protective Factors and Decrease Symptomatology. J. Am. Coll. Health 2010, 56, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonnier, E.; Trémolière, B.; Baussard, L.; Goncalves, A.; Lespiau, F.; Philippe, A.G.; Le Vigouroux, S. Effects of an online self-help intervention on university students’ mental health during COVID-19: A non-randomized controlled pilot study. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 5, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küchler, A.M.; Schultchen, D.; Dretzler, T.; Moshagen, M.; Ebert, D.D.; Baumeister, H. A Three-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Effectiveness, Acceptance, and Negative Effects of StudiCare Mindfulness, an Internet- and Mobile-Based Intervention for College Students with No and “On Demand” Guidance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.; Halvorson, M.; Lengua, L.J. A mindfulness-based promotive coping program improves well-being in college undergraduates. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanilevici, M.; Reuveni, O.; Lev-Ari, S.; Golland, Y.; Levit-Binnun, N. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Increases Mental Wellbeing and Emotion Regulation during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Synchronous Online Intervention Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 720965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stächele, T.; Domes, G.; Wekenborg, M.; Penz, M.; Kirschbaum, C.; Heinrichs, M. Effects of a 6-Week Internet-Based Stress Management Program on Perceived Stress, Subjective Coping Skills, and Sleep Quality. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, D.D.; Lehr, D.; Heber, E.; Riper, H.; Cuijpers, P.; Berking, M. Internet- and mobile-based stress management for employees with adherence-focused guidance: Efficacy and mechanism of change. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2016, 42, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmqvist, B.; Carlbring, P.; Andersson, G. Internet-delivered treatments with or without therapist input: Does the therapist factor have implications for efficacy and cost? Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2007, 7, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattie, E.G.; Adkins, E.C.; Winquist, N.; Stiles-Shields, C.; Wafford, Q.E.; Graham, A.K. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression, Anxiety, and Enhancement of Psychological Well-Being Among College Students: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, S.; Licinio, J. Qualitative literature review of the prevalence of depression in medical students compared to students in non-medical degrees. Acad. Psychiatry 2015, 39, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthran, R.; Zhang, M.W.B.; Tam, W.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: A meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm-Hadulla, R.M.; Hofmann, F.H.; Sperth, M.; Funke, J. Psychische Beschwerden und Störungen von Studierenden. Psychotherapeut 2009, 54, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerolini, S.; Zagaria, A.; Franchini, C.; Maniaci, V.G.; Fortunato, A.; Petrocchi, C.; Speranza, A.M.; Lombardo, C. Psychological Counseling among University Students Worldwide: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1831–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, T.G.; Li, S.; Saunders, R.; Fonagy, P. University students’ use of mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2022, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T. Frequently Used Coping Scales: A Meta-Analysis. Stress Health 2015, 31, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klauer, T. Stressbewältigung. Psychotherapeut 2012, 57, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).