Spiritual Care through the Lens of Portuguese Palliative Care Professionals: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting, Participants, and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

2.5. Ethics

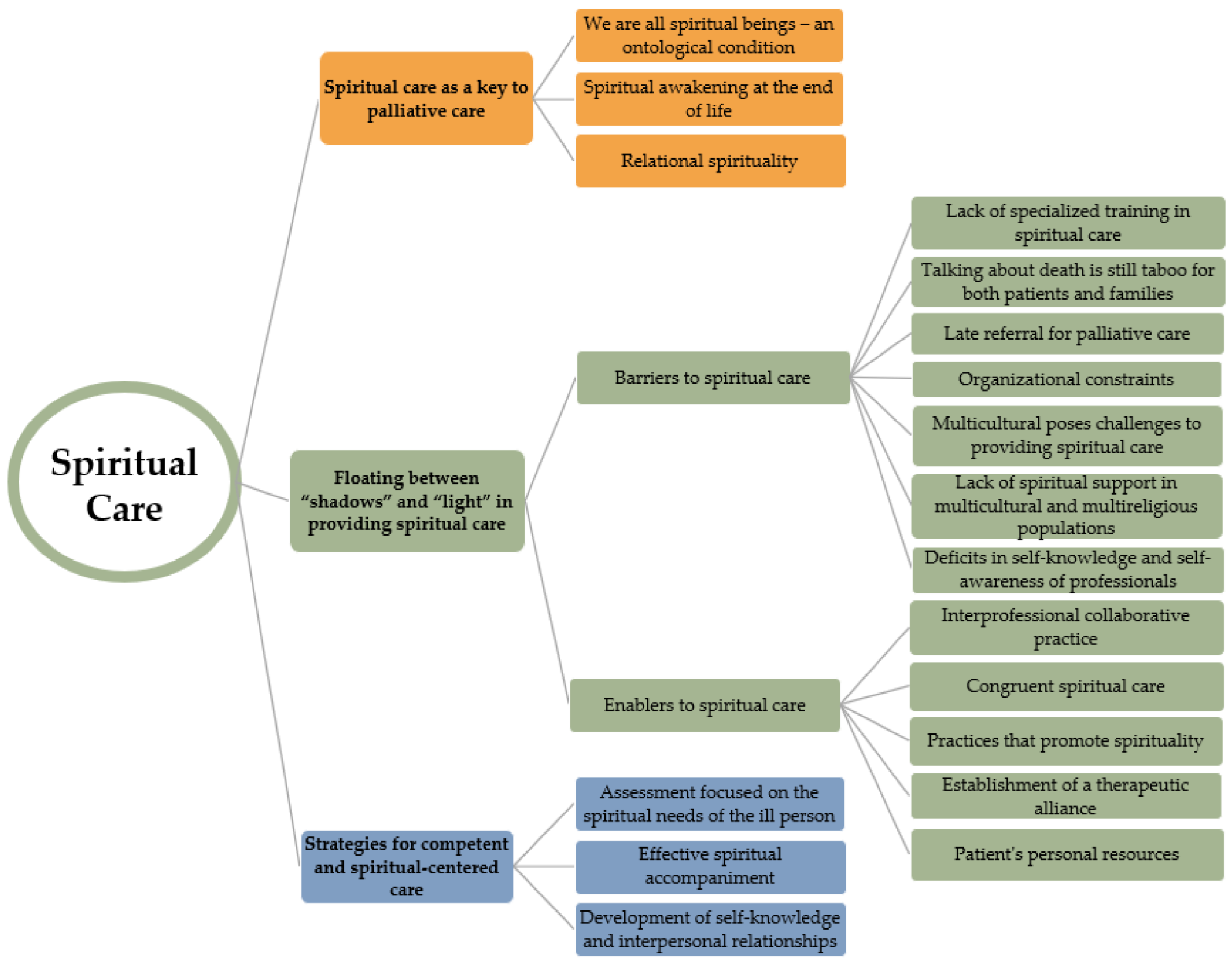

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. Spiritual Care as Key to Palliative Care

- (1)

- We are all spiritual beings—an ontological condition

(P7; social worker): We are spiritual beings, and throughout our lives we think […] about our existence. Let’s look at our past, see our present, and let’s also think about our future. Therefore, spirituality is something that, in my opinion, is built throughout our lives and deeply determined by religious contexts.

(P4; nurse): Spirituality […], and having faith, are what characterize the person themselves, the essence of the person, and what defines them, in addition to the attributes they may have, physically, professionally, and socially.

(P6; psychologist): Spirituality is part of our life […], there is this need, a support, a basis for spiritual care at the end of life, in which there has to be a meaning for it or an attempt at peace in this terminal process.

(P11; nurse): I think it’s something beyond what we can see. […] it ends up being something very personal, something very individual.

- (2)

- Spiritual awakening at the end of life

(P13; physician): The end of life is one of the most important phases to be worked on […] in palliative care. Indeed, it is at this stage of life that the person tries to find meaning in the illness and in the life and suffering they are experiencing. It’s about waking up, accepting the illness, and finding meaning for your life, your being, and your existence.

(P6; psychologist): Often this peace is found not only in the relationship with others, whether health professionals, family and friends, but in the transcendent relationship with a higher entity. When it is not named, when there is no particular name, they often tell me that they need to believe that there will be a higher entity that will guide their meaning in life; and which will certainly welcome them, they don’t know how, but they feel an awakening to the spiritual dimension.

(P7; social worker): Although spirituality is something that, in my opinion, is built throughout our lives, in palliative care it takes on another proportion, another dimension.

- (3)

- Relational spirituality

(P7; social worker): […] Spiritual support for me […] is an extremely important dimension, because it will allow us to soothe the patient so that the family can be more soothed. We will allow, without a doubt, a calmer death […]. And I think it is our obligation as palliative care professionals, we also have this responsibility to know that this person can die in peace. It is our responsibility to help them in this task of pacifying themselves, no matter who they are […] so that when the time of death actually arrives, it will be as calm and serene as possible so that this life has not been lived in vain.

(P6; psychologist): The issue of spirituality goes hand in hand with the work we do towards reconciliation, pacifying families with the patient, the patient with themselves, and resolving other issues that concern that particular person, which provides openness to think about spiritual issues and to surrender to this more humanistic and self-loving side.

(P5; physician): I think that spirituality is very important in palliative care because it is an important determinant of the patient’s well-being and the patient’s interaction with health professionals and even interferes with the results that we can have in terms of global control of symptoms, in addition to the spiritual well-being itself.

3.2.2. Floating between “Shadows” and “Light” in Providing Spiritual Care

Barriers to Spiritual Care

(P7; Social worker): If I had specific training in spiritual care, it would help me approach situations differently and give me other skills. Without a doubt, it would be important.

(P4; nurse): I think it is very important for people to know because it is very difficult for us to experience what others are experiencing during the terminal phase. But I think that training in the area of spirituality is very important to become more sensitive to it […], and in this way we can help.

(P3; nurse): Training is what makes all the difference. I think that training makes a difference, even though I don’t have any and there isn’t training of this type. But I believe it enables us to manage all these emotions and deal with issues of transcendence.

(P5; physician): Basically, doctors and nurses are more trained to control symptoms than to deal with existential issues […]; it is extremely important to have training in spiritual care. It is an area that must be transversal to all health professionals, regardless of their area, so that we can all as a team identify the spiritual needs of the patient and be able to help in the best way or promote the patient to improve their spirituality.

(P1; physician): Talking about death is something that families don’t try to do. There are few patients or families who have the time or the openness to talk about these things.

(P2; nurse): Families often don’t realize that it’s not just a symptomatic lack of control, and that’s why they end up not giving importance to the moments when professionals are supporting existential suffering. They prefer not to talk about the subject.

(P3; nurse): Some families sometimes have different opinions than the patient and others are also not so receptive to our presence or even interfere with the patient’s wishes.

(P13; physician): Many times we are unable to provide adequate spiritual support as referrals are late […]; they arrive late.

(P1; physician): Many patients come here in the last hours/days of their lives […], so we often cannot understand what the patient wants, their spiritual needs, how we can help them to calm down with themselves and others.

(P12; social worker): When we have a patient, we must be focused on them, but it is not easy to monitor so many people… The feeling I have is that I am always against the clock […].

(P4; nurse): We should have more time for spiritual care, but that doesn’t happen due to a lack of resources. We do our best!

(P7; social worker): The biggest barrier? Time, time. Literally, time. Because for spiritual care you need time. On the other hand, having a higher ratio of professionals in these palliative teams would help a lot.

(P1; physician): We have had many immigrants, people who come to our country and who belong to Muslim, Ismaili, or Hindu communities, and this represents a challenge for palliative care teams as we do not have references in the community who can help us.

(P10; nurse): A reality that is changing in Portugal is more multiculturalism. Because there is another type of spiritual need you are not so familiar with, I feel that it is a difficulty.

(P12; Social worker): When we have people of other faiths […], who do we turn to? Apart from the chaplain, we have no one here who can help us. For example, if the patient wanted to speak to the Imam, we would have no way of offering this spiritual service.

(P6; Psychologist): Portugal is a country with a Catholic tradition, which means that we only have a priest as a member of the team. It is not easy to have a spiritual assistant available for each religious belief or confession. We end up, whether we like it or not, relying solely on the support of the Catholic priest.

(P8; nurse): We all have personal difficulties, we are human, and we are not well every day, so despite trying to abstract myself, I assume that these difficulties could act as an obstacle in satisfying the spiritual needs of our patients.

(P13; physician): The problem lies in the poor self-knowledge of professionals. As a spiritual being, I am still making my way and sometimes I don’t feel comfortable bringing up the subject of spirituality because I still haven’t found all my answers […]; this requires us to do a lot of introspection and work ourselves, which is not always easy.

(P12; social worker): My main barrier is […] I don’t have spirituality refined within me. And therefore, I confess that I try to avoid this issue a little. If the question is objective, I tend to answer, if it’s not objective, I confess that I don’t raise the topic either, or I don’t ask many questions about the topic. […] Because the feeling I have is that if I do it, it will sound false or unprofessional because I don’t know how much I believe it, and so I don’t want to invent either.

Enablers to Spiritual Care

(P12; social worker): I’m lucky to work in a place where we work as a team […] I think we complement each other. That’s the biggest facilitator, the fact that we work as a team and support each other and complement each other.

(P5; physician): It is a facilitator, a way in which palliative teams are designed with their pluridisciplinarity and their attention focused on the needs of the patient and family, which means that we can be alert to spiritual needs and can act as a team, each giving their contribution.

(P1; physician): I think it is extremely important that we know how to get to the heart of the matter and have the competence to “touch” spiritual issues that may be sensitive to the patient without causing harm to the patient.

(P7; social worker): We are there to facilitate spiritual care according to what the patient considers to be best for them.

(P6; psychologist): I think there has to be an effective combination of our academic, human, and moral training and our level of sensitivity and ability to surrender to others.

(P15; nurse): If the person feels comfortable addressing this issue, we strive to fulfill their wishes or desires. Above all, we are facilitators, striving to adjust spiritual care to each person’s needs.

(P1; physician): For many patients, praying the rosary is a very important activity.

(P5; physician): We already had the example of a lady who went to the sanctuary of Fátima to attend mass; she went with her family (she used the magic ambulance project, which aims to fulfill significant desires). I remember that the lady that day was even more interactive than usual. She returned to the unit the same day and the following day she died. We believe that that trip was calming for her and her family and allowed her to leave in peace.

(P9; nurse): Promoting activities that already happened before in their daily lives, such as praying the rosary and receiving communion, allows them to express their spirituality and talk about it openly.

(P14; nurse): I remember, for example, the permanence of significant objects, such as the rosary or a saint on the bedside table, which were important to some people. And, by allowing these objects and symbols, patients became more comfortable.

(P5; physician): While it is difficult to talk openly about spirituality, I try to understand what is bothering the patient; I try to provide an environment of trust so that the patient can explain to me what is happening and what they feel.

(P6; psychologist): Therefore, in this process of active listening and within the spirit of mission, one should listen to the other person’s life story and try to help them in accordance with their personality and their life goals at that moment. The therapeutic relationship is of paramount importance in the support of healing.

(P7; social worker): Empathy towards others is fundamental. […] In other words, as a professional, you have to be aware that this could be important for that person. And when that happens, your empathy toward others, your way of being, and your sensibility increase.

(P9; nurse): Sometimes when nothing else works in terms of medical intervention, patients will seek strength in faith, allowing them to better accept their situation.

(P6; psychologist): Patients often say “I’m prepared to die, I’m prepared to leap” […] and they find inner peace in their spirituality and self-knowledge.

3.2.3. Strategies for Competent and Spiritual-Centered Care

(P1; physician): Almost always, we end up asking if patients have any beliefs, any religious practices, any spiritual needs. This assessment is essential to get closer to their particularities.

(P2; nurse): When there is an opportunity, we try to talk about spiritual practices, whether you are a believer or not, whether you believe in a superior being […] and then see how we can help.

(P6; psychologist): In my clinical practice, I try to understand if people are calm in their spirituality or if they need help finding inner peace.

(P3; nurse): Spiritual support helps people accept death, being with them, supporting them. Our presence, being with the person, and asking them what they need to do to feel at peace, are fundamental elements in spiritual care.

(P13; physician): Accompanying means talking openly about spirituality, about meanings […] but it is above all being there, listening, and not judging. […] There may be aspects that do not make sense to us as spiritual beings. However, being there and making an effort in this process is the most important thing.

(P1; physician): In-service training using roleplay and practical exercises helps a lot in communicating with patients and families. Having moments of self-knowledge promoted as a team helps us deal with complex patients, and this increases our competency.

(P6; psychologist): Spiritual retreats awaken us to spiritual well-being but also help our patients. After all, if we are not well and do not take care of ourselves, the helping relationship is compromised.

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferrell, B.R.; Twaddle, M.L.; Melnick, A.; Meier, D.E. National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care Guidelines, 4th Edition. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1684–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.; Ferrell, B.; Virani, R.; Otis-Green, S.; Baird, P.; Bull, J.; Chochinov, H.; Handzo, G.; Nelson-Becker, H.; Prince-Paul, M.; et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. J. Palliat. Med. 2009, 12, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. ‘Total pain’, disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958–1967. Soc Sci Med. 1999, 49, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. 2002. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Benito, E.; Dones, M.; Babero, J. El acompañamiento espiritual en cuidados paliativos. Psicooncología 2016, 13, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, P.E. Suffering a Healthy Life-On the Existential Dimension of Health. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 803792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D. Cicely Saunders: A Life and Egacy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, E.J. The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, A. Espiritualidade [Spirituality]. In Manual de Cuidados Paliativos, 3rd ed.; Barbosa, A., Pina, P., Tavares, F., Neto, I.G., Eds.; Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016; pp. 737–780. [Google Scholar]

- Best, M.; Leget, C.; Goodhead, A.; Paal, P. An EAPC white paper on multi-disciplinary education for spiritual care in palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koper, I.; Pasman, H.R.W.; Schweitzer, B.P.M.; Kuin, A.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D. Spiritual care at the end of life in the primary care setting: Experiences from spiritual caregivers-a mixed methods study. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchalski, C.M.; Vitillo, R.; Hull, S.K.; Reller, N. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, W.T.; Maddalena, V.; Njiwaji, M.; Darrell, D.M. The role of spirituality at end of life in Nova Scotia’s Black community. J. Relig. Spiritual. Soc. Work. 2014, 33, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalani, N.; Duggleby, W.; Olson, J. Rise Above: Experiences of Spirituality Among Family Caregivers Caring for Their Dying Family Member in a Hospice Setting in Pakistan. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 21, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.R.; Kinloch, K.; Groves, K.E.; Jack, B.A. Meeting patients’ spiritual needs during end-of-life care: A qualitative study of nurses’ and healthcare professionals’ perceptions of spiritual care training. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierstra, I.R.; Liefbroer, A.I.; Post, L.; Tromp, T.; Körver, J. Addressing spiritual needs in palliative care: Proposal for a narrative and interfaith spiritual care intervention for chaplaincy. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2023, 29, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, R.D.; Viftrup, D.T.; Hvidt, N.C. The Process of Spiritual Care. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 674453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C. Nurses and Patients’ Perspectives on Spiritual Health Assessment. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, L.; Ganzevoort, R.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. Transcending the suffering in cancer: Impact of a spiritual life review intervention on spiritual re-evaluation, spiritual growth and psycho-spiritual wellbeing. Religions 2020, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasair, S. A Narrative Approach to Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Health Care. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 1524–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, P. Spirituality, religion and palliative care. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2014, 3, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.A.; Kim, D.B.; Koh, S.J.; Koh, S.J.; Park, M.H.; Park, H.Y.; Yoon, D.H.; Yoon, S.J.; Lee, S.J.; Choi, J.E.; et al. Spiritual Care Guide in Hospice∙Palliative Care. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2023, 26, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, M.; Butow, P.N.; Olver, I.N. Do patients want doctors to talk about spirituality? A systematic literature review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.M.; Fan, L. Impact of spiritual care on the spiritual and mental health and quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, A.C.T.; de Rezende Coelho, M.C.; Coutinho, F.B.; Borges, L.H.; Lucchetti, G. The influence of spirituality and religiousness on suicide risk and mental health of patients undergoing hemodialysis. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 80, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrad, R.; Cosentino, C.; Keasley, R.; Sulla, F. Spiritual care in nursing: An overview of the measures used to assess spiritual care provision and related factors amongst nurses. Acta Biomed. 2019, 90, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Baptista Peixoto Befecadu, F.; Da Rocha Rodrigues, M.G.; Larkin, P.; Pautex, S.; Dixe, M.A.; Querido, A. Exercising Hope in Palliative Care Is Celebrating Spirituality: Lessons and Challenges in Times of Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 933767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauser, K.E.; Fitchett, G.; Handzo, G.F.; Johnson, K.S.; Koenig, H.G.; Pargament, K.I.; Puchalski, C.M.; Sinclair, S.; Taylor, E.J.; Balboni, T.A.; et al. State of the Science of Spirituality and Palliative Care Research Part I: Definitions, Measurement, and Outcomes. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance [WPCA]. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life; WHO: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S.; McConnell, S.; Raffin Bouchal, S.; Ager, N.; Booker, R.; Enns, B.; Fung, T. Patient and healthcare perspectives on the importance and efficacy of addressing spiritual issues within an interdisciplinary bone marrow transplant clinic: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallurupalli, M.; Lauderdale, K.; Balboni, M.J.; Phelps, A.C.; Block, S.D.; Ng, A.K.; Kachnic, L.A.; Vanderweele, T.J.; Balboni, T.A. The role of spirituality and religious coping in the Quality of Life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J. Support. Oncol. 2012, 10, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Hsieh, C.; Shih, Y.; Lin, Y. Spiritual well-being of patients with chronic renal failure: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2461–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britt, K.C.; Boateng, A.C.; Zhao, H.; Ezeokonkwo, F.C.; Federwitz, C.; Epps, F. Spiritual Needs of Older Adults Living with Dementia: An Integrative Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gijsberts, M.H.E.; Liefbroer, A.I.; Otten, R.; Olsman, E. Spiritual Care in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of the Recent European Literature. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, E.J.; Powell, R.A. Valuing the Spiritual. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, M.C.; Vivat, B.; Gijsberts, M.-J. Spiritual Care in Palliative Care. Religions 2023, 14, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSherry, W.; Jamieson, S. The qualitative findings from an online survey investigating nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 3170–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, B.; Connolly, M. Spirituality in palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care. 2023, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, T.A.; Fitchett, G.; Handzo, G.F.; Johnson, K.S.; Koenig, H.G.; Pargament, K.I.; Puchalski, C.M.; Sinclair, S.; Taylor, E.J.; Steinhauser, K.E.; et al. State of the Science of Spirituality and Palliative Care Research Part II: Screening, Assessment, and Interventions. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, T.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Doan-Soares, S.D.; Long, K.N.; Ferrell, B.R.; Fitchett, G.; Koenig, H.G.; Bain, P.A.; Puchalski, C.; Steinhauser, K.E.; et al. Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health. JAMA 2022, 328, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, L.; Young, T.; Vermandere, M.; Stirling, I.; Leget, C. Research subgroup of European Association for Palliative Care Spiritual Care Taskforce. Research priorities in spiritual care: An international survey of palliative care researchers and clinicians. J. Pain. Symptom. Manag. 2014, 48, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Benito, E.; Dixe, M.A.; Dones, M.; Specos, M.; Querido, A. SPACEE Protocol: “Spiritual Care Competence” in PAlliative Care Education and PracticE: Mixed-Methods Research in the Development of Iberian Guidelines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, J.; Austin, Z. Qualitative research: Data collection, analysis, and management. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 68, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts, K.; Brundage, J.; Vandenberghe, F. Towards a critical realist epistemology? J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2020, 50, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Z.; Wu, P.; Luo, A.; Ho, T.L.; Chen, C.Y.; Cheng, S.Y. Perceptions and practices of spiritual care among hospice physicians and nurses in a Taiwanese tertiary hospital: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Navarro, E.B.; Medina-Ortega, A.; García Navarro, S. Spirituality in Patients at the End of Life-Is It Necessary? A Qualitative Approach to the Protagonists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett, D.K. Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.; Addicott, K.; Rosa, W.E. Spiritual Care as a Core Component of Palliative Nursing. Am. J. Nurs. 2023, 123, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mount, B.M.; Boston, P.M.; Cohen, S.R. Healing connections: On moving from suffering to a sense of wellbeing. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2007, 33, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, F.; Nunes, R. The interface between psychology and spirituality in palliative care. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Murray, D. The multiple determinants of religious behaviors and spiritual beliefs on well-being. J. Spirit. Ment. Health 2011, 13, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożek, A.; Nowak, P.F.; Blukacz, M. The Relationship Between Spirituality, Health-Related Behavior, and Psychological Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasair, S.; Sinclair, S. Family and patient spiritual narratives in the ICU: Bridging disclosures through compassion. In Families in the Intensive Care Unit: A Guide to Understanding, Engaging, and Supporting at the Bedside; Netzer, G., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Haufe, M.; Leget, C.; Potma, M.; Teunissen, S. How can existential or spiritual strengths be fostered in palliative care? An interpretative synthesis of recent literature. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corneille, J.S.; Luke, D. Spontaneous Spiritual Awakenings: Phenomenology, Altered States, Individual Differences, and Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 720579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, A.; Oroojan, A.A.; Rassouli, M.; Ashrafizadeh, H. Explanation of near-death experiences: A systematic analysis of case reports and qualitative research. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1048929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, L.; Byrne, E.; Deegan, A.; Dunne, S.; Gallagher, P. A qualitative meta-synthesis examining spirituality as experienced by individuals living with terminal cancer. Health Psychol. Open 2022, 9, 20551029221121526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, J.; Glenn, E.; Paine, D.; Sandage, S. What is the “Relational” in Relational Spirituality? A Review of Definitions and Research Directions. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 2016, 18, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Dixe, M.A.; Querido, A. Perceived Barriers to Providing Spiritual Care in Palliative Care among Professionals: A Portuguese Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, G.; Hashemi, M.S.; Hemati, Z. Barriers to Providing Spiritual Care from a Nurses’ Perspective: A Content Analysis Study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2022, 27, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selby, D.; Seccaraccia, D.; Huth, J.; Kurrpa, K.; Fitch, M.A. A qualitative analysis of a healthcare professional’s understanding and approach to management of spiritual distress in an acute care setting. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Shin, D.W.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, C.H.; Baek, Y.J.; Mo, H.N.; Song, M.O.; Park, S.A.; do Moon, H.; Son, K.Y. Addressing the religious and spiritual needs of dying patients by healthcare staff in Korea: Patient perspectives in a multi-religious Asian country. Psychooncology 2012, 21, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.; Lulav-Grinwald, D.; Bar-Sela, G. Cultural differences in spiritual care: Findings of an Israeli oncologic questionnaire examining patient interest in spiritual care. BMC Palliat. Care 2014, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurs, J.; Breedveld, R.; Geer, J.; Leget, C.; Smeets, W.; Koorneef, R.; Vissers, K.; Engels, Y.; Wichmann, A. Role-Perceptions of Dutch Spiritual Caregivers in Implementing Multidisciplinary Spiritual Care: A National Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtania, M.; Katta, A. Essential Elements of Home-based Palliative Care Model: A Rapid Review. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2023, 29, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydari, H.; Hojjat-Assari, S.; Almasian, M.; Pirjani, P. Exploring Health Care Providers’ Perceptions about Home-based Palliative Care in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.C. The essence of spiritual care: A phenomenological enquiry. Palliat. Med. 2002, 16, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinedo, M.T.; Jiménez, J.C. Cuidados del personal de enfermería en la dimensión espiritual del paciente. Revisión sistemática. Cult. Cuid. Rev. Enfermería Humanid. 2017, 48, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Diego-Cordero, R.; López-Tarrida, Á.C.; Linero-Narváez, C.; Galán González-Serna, J.M. “More Spiritual Health Professionals Provide Different Care”: A Qualitative Study in the Field of Mental Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyoke, P.; Stephenson, B. Organization-level principles and practices to support spiritual care at the end of life: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito, E.; Oliver, A.; Galiana, L.; Barreto, P.; Pascual, A.; Gomis, C.; Barbero, J. Development and validation of a new tool for the assessment and spiritual care of palliative care patients. J. Pain Sympt. Manag. 2014, 47, 1008–1018.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumbold, B. (Ed.) Spirituality and Palliative Care; Oxford University Press: South Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Daaleman, T.P.; Usher, B.M.; Williams, S.W.; Rawlings, J.; Hanson, L.C. An exploratory study of spiritual care at the end of life. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008, 6, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinson, L.P.; McSherry, W.; Kevern, P. Spirituality in preregistration nurse education and practice: A review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, L.E.; Brighton, L.J.; Sinclair, S.; Karvinen, I.; Egan, R.; Speck, P.; InSpirit Collaborative. Patients’ and caregivers’ needs, experiences, preferences and research priorities in spiritual care: A focus group study across nine countries. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykkje, L.; Søvik, M.B.; Ross, L.; McSherry, W.; Cone, P.; Giske, T. Educational interventions and strategies for spiritual care in nursing and healthcare students and staff: A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 1440–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvidt, N.C.; Nielsen, K.T.; Kørup, A.K.; Prinds, C.; Hansen, D.G.; Viftrup, D.T.; Hvidt, E.A.; Hammer, E.R.; Falkø, E.; Locher, F.; et al. What is spiritual care? Professional perspectives on the concept of spiritual care identified through group concept mapping. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paal, P.; Helo, Y.; Frick, E. Spiritual Care Training Provided to Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review. J. Pastor. Care Counsel. 2015, 69, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodhead, L.; Partridge, C.; Kawanami, H. Religions in the Modern World: Traditions and Transformations, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Olsman, E.; Leget, C.; Willems, D. Palliative care professionals’ evaluations of the feasibility of a hope communication tool: A pilot study. Prog. Palliat. Care 2015, 23, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leget, C. Art of living, art of dying. Spiritual Care for a Good Death; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rasinski, K.A.; Kalad, Y.G.; Yoon, J.D.; Curlin, F.A. An assessment of US physicians’ training in religion, spirituality, and medicine. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 944–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchalski, C.; Jafari, N.; Buller, H.; Haythorn, T.; Jacobs, C.; Ferrell, B. Interprofessional spiritual care education curriculum: A milestone toward the provision of spiritual care. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cone, P.H.; Lassche-Scheffer, J.; Bø, B.; Kuven, B.M.; McSherry, W.; Owusu, B.; Ross, L.; Schep-Akkerman, A.; Ueland, V.; Giske, T. Strengths and challenges with spiritual care: Student feedback from the EPICC Spiritual Care Self-Assessment Tool. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 6923–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestenbaum, A.; Fitchett, G.; Galchutt, P.; Labuschagne, D.; Varner-Perez, S.E.; Torke, A.M.; Kamal, A.H. Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Spirituality in Serious Illness. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.M.; Sbrana, A.; Ferrell, B.; Jafari, N.; King, S.; Balboni, T.; Miccinesi, G.; Vandenhoeck, A.; Silbermann, M.; Balducci, L.; et al. Interprofessional spiritual care in oncology: A literature review. ESMO Open 2019, 4, e000465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.; Ferrell, B.R.; Borneman, T.; DiFrances Remein, C.; Haythorn, T.; Jacobs, C. Implementing quality improvement efforts in spiritual care: Outcomes from the interprofessional spiritual care education curriculum. J. Health Care Chaplain 2022, 28, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syihabuddin, S. Spiritual pedagogy: An analysis of the foundation of values in the perspective of best performing teachers. Int. J. Educ. 2017, 10, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Song, D. Moving toward a spiritual pedagogy in L2 education: Research, practice, and applications. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 978054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, M.; John, D.; Hochheimer, J.L. Spirituality: Theory, Praxis and Pedagogy; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, M.L.; Reis-Pina, P. The Physician and End-of-Life Spiritual Care: The PALliatiVE Approach. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2022, 39, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, S.; Wane, N. Educating courageously: Transformative pedagogy infusing spirituality in K-12 education for fostering civil society and democracy. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 115, 102017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 20 December 2023).

| Participants | Age (Years) | Sex | Religious Affiliation | Professional Category | Professional Experience (Years) | Years of Work in Palliative Care | Training in Spiritual Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 34 | Female | Catholic | Physician | 8 | 1 | No |

| P2 | 50 | Female | Catholic | Nurse | 29 | 2 | No |

| P3 | 38 | Female | None | Nurse | 16 | 2 | No |

| P4 | 46 | Female | Catholic | Nurse | 22 | 2 | No |

| P5 | 36 | Female | None | Physician | 10 | 4 | No |

| P6 | 47 | Female | Catholic | Psychologist | 18 | 13 | Yes |

| P7 | 36 | Female | None | Social worker | 8 | 3 | No |

| P8 | 30 | Female | Catholic | Nurse | 8 | 2 | Yes |

| P9 | 37 | Female | Catholic | Nurse | 13 | 2 | No |

| P10 | 37 | Female | Catholic | Nurse | 8 | 2 | No |

| P11 | 33 | Female | Catholic | Nurse | 5 | 2 | No |

| P12 | 36 | Female | Catholic | Social worker | 10 | 6 | No |

| P13 | 37 | Female | Catholic | Physician | 12 | 6 | No |

| P14 | 36 | Male | Catholic | Nurse | 14 | 1 | No |

| P15 | 45 | Female | Catholic | Nurse | 23 | 2 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matos, J.; Querido, A.; Laranjeira, C. Spiritual Care through the Lens of Portuguese Palliative Care Professionals: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020134

Matos J, Querido A, Laranjeira C. Spiritual Care through the Lens of Portuguese Palliative Care Professionals: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(2):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020134

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatos, Juliana, Ana Querido, and Carlos Laranjeira. 2024. "Spiritual Care through the Lens of Portuguese Palliative Care Professionals: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 2: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020134

APA StyleMatos, J., Querido, A., & Laranjeira, C. (2024). Spiritual Care through the Lens of Portuguese Palliative Care Professionals: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14020134