The Moderating Role of Gender and Mediating Role of Hope in the Performance of Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Resilience

2.2. Hope

2.3. Psychological Resilience and Hope

2.4. Gender Difference

2.5. Individual Performance

2.6. The Effect of Resilience, Hope and Gender on Individual Performance

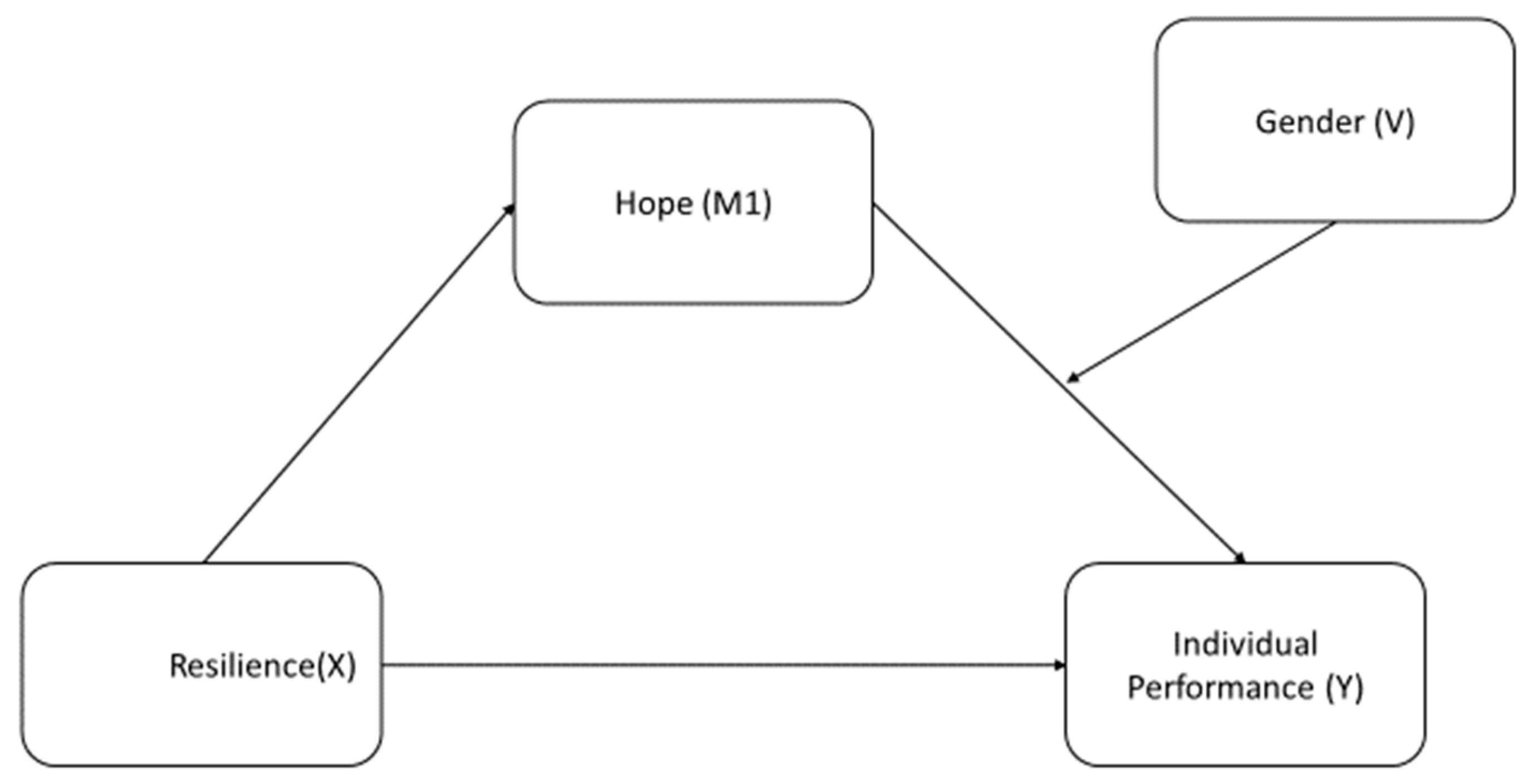

3. The Study

3.1. Aims

3.2. Design

3.3. Sample/Participants

3.4. Data Collection

3.4.1. Demographic Characteristics of Healthcare Professionals and Evaluation Form

3.4.2. Brief Resilience Scale

3.4.3. Continuous Hope Scale

3.4.4. Individual Performance Scale

3.5. Ethical Considerations

3.6. Data Analysis

3.7. Validity and Reliability/Rigor

4. Results/Findings

4.1. Stepwise Regression Analysis

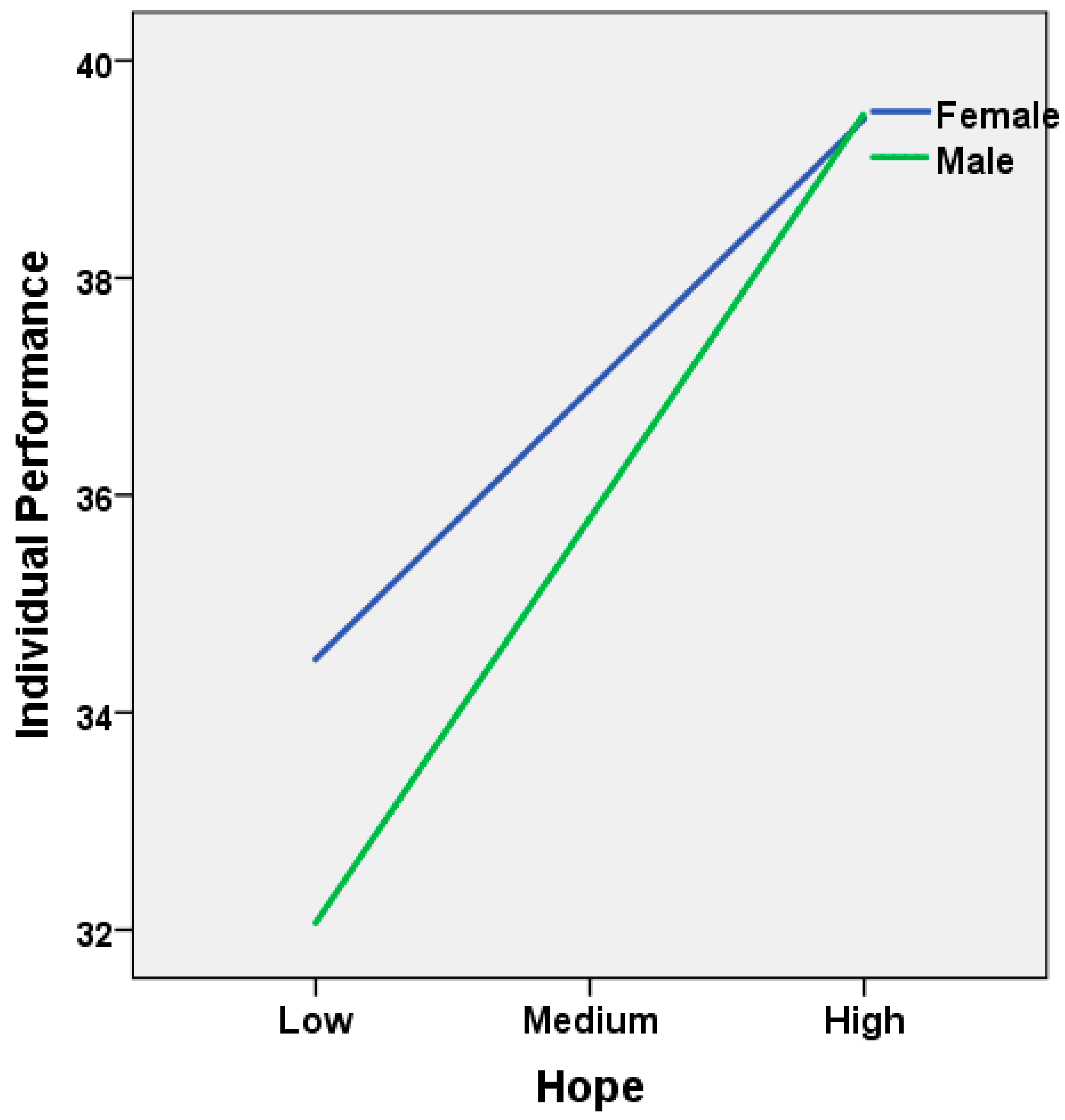

4.2. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological capital: Investing and developing positive organizational behavior. Posit. Organ. Behav. 2007, 1, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Khan, M.M.; Shakeel, S.; Mujtaba, B.G. Impact of psychological capital on performance of public hospital nurses: The mediated role of job embeddedness. Public Organ. Rev. 2021, 22, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, L.; Drakontaides, M.; Hadjicharalambous, D. Psychological resilience, hope, and adaptability as protective factors in times of crisis: A study in greek and cypriot society during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Educ. Res. 2020, 2, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grözinger, A.C.; Wolff, S.; Ruf, P.J.; Moog, P. The power of shared positivity: Organizational psychological capital and firm performance during exogenous crises. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 689–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Peterson, S.J. The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2010, 21, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Li, W. The psychological capital of Chinese workers: Exploring the relationship with performance. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2005, 1, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhao, X.W.; Yang, L.B.; Fan, L.H. The impact of psychological capital on job embeddedness and job performance among nurses: A structural equation approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sui, Y.; Luthans, F.; Wang, D.; Wu, Y. Impact of authentic leadership on performance: Role of followers’ positive psychological capital and relational processes. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.B. Life Experiences and Resilience in College Students: A Relationship Influenced by Hope and Mindfulness. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C.R.; Rand, K.L.; Sigmon, D.R. Hope theory a member of the positive psychology family. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder Shane, C.R., Lopez, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, C.M.; Luthans, F. Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 774–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirsel, M.T.; Erat Ocak, L.; Kara, H. İşyerinde kişilerarasi ilişki tarzlari ve bireysel performans arasindaki ilişkide psikolojik dayanikliliğin araci rolü. Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli Üniversitesi SBE Derg. 2022, 12, 2350–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çam, O.; Büyükbayram, A. Nurses’ resilience and effective factors. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 8, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health COVID-19 Information Platform Home Page. Available online: https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/ (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Snyder, C.R.; Feldman, D.B.; Taylor, J.D.; Schroeder, L.L.; Adams, V.H., III. The roles of hopeful thinking in preventing problems and enhancing strengths. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 2000, 9, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Reed, M.G.J. Resilience in development. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder Shane, C.R., Lopez, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V.E. Man’s Search for Meaning; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Peterson, S.J.; Avolio, B.J.; Hartnell, C.A. An investigation of the relationships among leader and follower psychological capital, service climate, and job performance. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 63, 937–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Harris, C.; Anderson, J.R.; Holleran, S.A.; Irving, L.M.; Sigmon, S.T.; Yoshinobu, L.; Gibb, J.; Langelle, C.; Harney, P. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, B.M.; Chaboyer, W.; Wallis, M. The influence of personal characteristics on the resilience of operating room nurses: A predictor study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W. The nature–nurture debates: 25 years of challenges in understanding the psychology of gender. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers-Levy, J.; Tybout, A.M. Schema congruity as a basis for product evaluation. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers-Levy, J.; Loken, B. Revisiting gender differences: What we know and what lies ahead. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers-Levy, J.; Maheswaran, D. Exploring differences in males’ and females’ processing strategies. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers-Levy, J.; Sternthal, B. Gender differences in the use of message cues and judgments. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.Y. “Said and done” versus “saying and doing” gendering practices, practicing gender at work. Gend. Soc. 2003, 17, 342–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.H.; Rodriguez Mosquera, P.M.; Van Vianen, A.E.; Manstead, A.S. Gender and culture differences in emotion. Emotion 2004, 4, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.P.; Anderson, E.R. Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaud, M.; Dugas, M.J.; Conway, M. Gender differences in worry and associated cognitive-behavioral variables. J. Anxiety Disord. 2003, 17, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlawat, S.; Budhiraja, A. Relation between creativity and hope: A study of gender difference. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2016, 7, 233–235. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, M.; Barahmand, U.; Roshannia, S. Differentiation of self and hope mediated by resilience: Gender differences. Can. J. Fam. Youth 2020, 12, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaven, P.; Ciarrochi, J. Parental styles, gender and the development of hope and self-esteem. Eur. J. Personal. Publ. Eur. Assoc. Personal. Psychol. 2008, 22, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šikýř, M. Best practices in human resource management: The source of excellent performance and sustained competitiveness. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2013, 2, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.M. Statistical Methods for Validation of Assessment Scale Data in Counseling and Related Fields; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I.; Berge, J.T. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967; Volume 226. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L. Revisiting sample size and number of parameter estimates: Some support for the N: Q hypothesis. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doğan, T. Kısa psikolojik sağlamlık ölçeği’nin Türkçe uyarlaması: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. J. Happiness Well-Being 2015, 3, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, S. Umudun Özyeterlik, Algılanan Sosyal Destek ve Kişilik Özelliklerinden Yordanması. Ph.D. Thesis, Gazi Üniversitesi. Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Ankara, Türkiye, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schepers, J.M. The construction and evaluation of a generic work performance questionnaire for use with administrative and operational staff. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2008, 34, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özpehlivan, M. The relationship among organizational communication, job satisfaction, individual performance and organizational commitment in different cultures. Bilecik Şeyh Edebali Üniversitesi Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2019, 4, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaqr, A.M. Remarks on the use of Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients in assessing relationships in ophthalmic data. Afr. Vis. Eye Health 2021, 80, a612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkind, N.; Rasmussen, K. Shapiro-Wilk Test for Normality. In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Çakı, N.; Aslan, M. Psikolojik sermayenin performans üzerindeki etkisinde algılanan örgütsel adaletin moderatör rolü. İşletme Araştırmaları Derg. 2022, 14, 2601–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdağ, F.; Ergün, N. Psychological resilience of healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Rep. 2020, 124, 2567–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Güler, A. Coronavirus anxiety, fear of COVID-19, hope and resilience in healthcare workers: A moderated mediation model study. Health Psychol. Rep. 2021, 9, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, L.H.; Choo, T.S. Relationships among parent’s hope, primary pupil’s hope with their academic achievement. JuKu J. Kurikulum Pengajaran Asia Pasifik 2020, 8, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gisinger, T.; Dev, R.; Kautzky, A.; Harreiter, J.; Raparelli, V.; Kublickiene, K.; GOING-FWD Consortium and the iCARE Study Team. Sex and gender impact mental and emotional well-being during COVID-19 pandemic: A european countries experience. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baguri, E.M.; Roslan, S.; Hassan, S.A.; Krauss, S.E.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z. How do self-esteem, dispositional hope, crisis self-efficacy, mattering, and gender differences affect teacher resilience during COVID-19 school closures? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G. National Cultural Dimensions. 2012. Available online: http://geert-hofstede.com/national-culture.html (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Forum, W.E. The Global Gender Gap Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-global-gender-gap-report-2018/ (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | N (%) | Professional Seniority (Years) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1–5 | 83 (20.1) | |

| Female | 229 (55.6) | 6–10 | 68 (16.5) |

| Male | 183 (44.4) | 11–15 | 58 (14.1) |

| Age | 16–20 | 52 (12.6) | |

| 20–29 | 91 (22.1) | 20 and over | 151 (36.7) |

| 30–39 | 108 (26.2) | Education | |

| 40–49 | 117 (28.4) | Associate of Science | 78 (18.9) |

| 50 and over | 96 (23.3) | Bachelor’s Degree | 146 (35.5) |

| Marital Status | Master’s Degree | 188 (45.6) | |

| Married | 251 (60.9) | ||

| Single | 161 (39.1) | ||

| Profession | |||

| Physician | 226 (54.9) | ||

| Nurse | 66 (16.0) | ||

| Other health personnel | 68 (16.5) | ||

| Administrative staff | 51 (12.4) | ||

| Missing | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Scales | (sd) | Range | |

| Resilience | 20.27 (5.26) | 6–30 | |

| Individual performance | 36.54 (5.87) | 12–45 | |

| Hope | 68.79 (12.70) | 25–96 | |

| Pathway thinking | 25.34 (4.83) | 7–32 | |

| Agency thinking | 24.4 (4.86) | 4–32 |

| Demographic Characteristics | Scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | Individual Performance | Hope | Pathway Thinking | Agency Thinking | |

| /median (IQR) | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 19 (6.5) | 37 (8) | 67.17 ± 12.4 | 25 (7) | 25 (6) |

| Male | 21 (8) | 37 (8) | 70.81 ± 12.8 | 27 (8) | 26 (6) |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.707 | 0.004 | 0.062 | 0.011 |

| Age | |||||

| 20–29 | 18.9 ± 4.9 * | 33.9 ± 6.1 * | 64.85 ± 11.9 | 23.93 ± 4.6 * | 22.61 ± 4.7 * |

| 30–39 | 19.04 ± 5.2 # | 36.12 ± 6.1 | 65.44 ± 12.8 * | 24.28 ± 5.1 | 23.19 ± 4.9 |

| 40–49 | 20.29 ± 5.2 | 37.63 ± 5.7 * | 69.35 ± 13.1 | 25.90 ± 4.6 * | 24.74 ± 4.8 |

| 50 and over | 22.81 ± 4.7 *# | 38.14 ± 4.4 | 75.60 ± 9.6 * | 27.16 ± 4.1 | 26.98 ± 3.6 * |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 20 (7) | 37 (8) | 69.39 ± 12.6 | 26 (6) | 26 (6) |

| Single | 19 (7) | 36 (10) | 67.85 ± 12.8 | 25 (7) | 25 (6) |

| p-value | 0.654 | 0.048 | 0.233 | 0.135 | 0.011 |

| Profession | |||||

| Physician | 20 (7) | 36.30 ± 6.2 | 70.04 ± 12.4 | 25 (0) | 26 (6) *# |

| Nurse | 20 (6) | 36.92 ± 5.0 | 68.90 ± 12.5 | 26 (5) | 25 (6) |

| Other health personal | 19 (6.75) | 36.89 ± 5.8 | 67.20 ± 12.1 | 25 (6) | 24 (6) # |

| Administrative staff | 20 (8) | 36.52 ± 5.4 | 64.41 ± 14.6 | 26 (8) | 24 (8) * |

| p-value | 0.297 | 0.831 | 0.077 | 0.676 | 0.017 |

| Professional Seniority (years) | |||||

| 1–5 | 19.20 ± 5.1 *# | 34.26 ± 6.4 *# | 65.33 ± 11.0 * | 24.07 ± 4.2 * | 22.98 ± 4.6 * |

| 6–10 | 18.58 ± 5.4 | 34.64 ± 6.5 | 64 ± 14.2 # | 23.57 ± 5.6 # | 22.08 ± 5.5 # |

| 11–15 | 20.06 ± 4.6 | 36.63 ± 4.7 | 67.5 ± 11.0 | 25.06 ± 3.9 | 23.81 ± 3.7 |

| 16–20 | 19.69 ± 6.3 # | 38.42 ± 5.6 * | 69.8 ± 15.7 | 26.11 ± 5.3 | 24.84 ± 5.4 |

| 20 and over | 21.88 ± 4.6 * | 37.94 ± 5.0 # | 73 ± 11.0 *# | 26.66 ± 4.3 *# | 26.26 ± 4.0 *# |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Education | |||||

| Associate of Science | 19.44 ± 5.1 | 35 (9) *# | 65.65 ± 13.3 * | 24 (8) * | 23 (5) *# |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 20.30 ± 5.5 | 37 (7) # | 68.93 ± 13.2 | 26 (7) | 25 (6) # |

| Master’s Degree | 20.57 ± 5.0 | 37 (8) * | 69.98 ± 11.8 * | 26 (6) * | 26 (6) * |

| p-value | 0.280 | 0.031 | 0.041 | 0.019 | <0.001 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Gender | 0.29 ** | - | |||||||||

| 3. Marital status | −0.45 ** | −0.11 * | - | ||||||||

| 4. Education | 0.44 ** | 0.09 | −0.16 ** | - | |||||||

| 5. Profession | −0.23 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.07 | −0.48 ** | - | ||||||

| 6. Professional Seniority | 0.89 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.45 ** | 0.37 ** | −0.16 ** | - | |||||

| 7. Resilience | 0.27 ** | 0.20 ** | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.23 ** | - | ||||

| 8. Hope | 0.32 ** | 0.16 ** | −0.06 | 0.11 * | −0.11 * | 0.28 ** | 0.73 ** | - | |||

| 9. Individual performance | 0.25 ** | −0.01 | −0.09 * | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.26 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.46 ** | - | ||

| 10. Agency thinking | 0.35 ** | 0.13 * | −0.13 * | 0.18 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.81 ** | 0.56 ** | - | |

| 11. Pathway thinking | 0.26 ** | 0.09 | −0.07 | 0.13 ** | −0.05 | 0.25 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.83 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.74 ** | - |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | β | 95% CI | B | β | 95% CI |

| Age | 1.66 ** | 0.31 ** | (1.13, 2.20) | 0.74 * | 0.13 * | (0.26, 1.22) |

| Gender | −1.32 * | −0.11 * | (−2.47, −0.16) | −1.20 * | −0.10 * | (−2.18, −0.23) |

| Profession | 0.39 | 0.07 | (−0.12, 0.90) | 0.63 * | 0.12 * | (0.19, 1.07) |

| Resilience | −0.02 | −0.02 | (−0.14, 0.08) | |||

| Hope | −0.05 | −0.12 | (−0.14, 0.03) | |||

| Pathway thinking | 0.18 * | 0.15 * | (0.04, 0.33) | |||

| Agency thinking | 0.51 ** | 0.42 ** | (0.36, 0.66) | |||

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.35 | ||||

| R2 change | 0.10 | 0.34 | ||||

| F statistics | 12.65 ** | 43.44 ** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cakiroglu, D.; Isıkhan, S.Y.; Coskun, H. The Moderating Role of Gender and Mediating Role of Hope in the Performance of Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121167

Cakiroglu D, Isıkhan SY, Coskun H. The Moderating Role of Gender and Mediating Role of Hope in the Performance of Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121167

Chicago/Turabian StyleCakiroglu, Demet, Selen Yılmaz Isıkhan, and Hamit Coskun. 2024. "The Moderating Role of Gender and Mediating Role of Hope in the Performance of Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 12: 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121167

APA StyleCakiroglu, D., Isıkhan, S. Y., & Coskun, H. (2024). The Moderating Role of Gender and Mediating Role of Hope in the Performance of Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121167