Understanding Reactions to Informative Process Model Interventions: Ambivalence as a Mechanism of Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conflict-Supporting Narratives and Interventions to Change Them

1.2. The Informative Process Model (IPM) and the Role of Ambivalence in Change

1.3. Attitude Change in Intractable Conflicts: Outcomes and Mechanisms

1.4. The Transition Between Precontemplation and Contemplation in Intractable Conflicts

1.5. The Present Research

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Procedure and Materials

2.1.3. Measures and Analytical Framework

2.2. Results

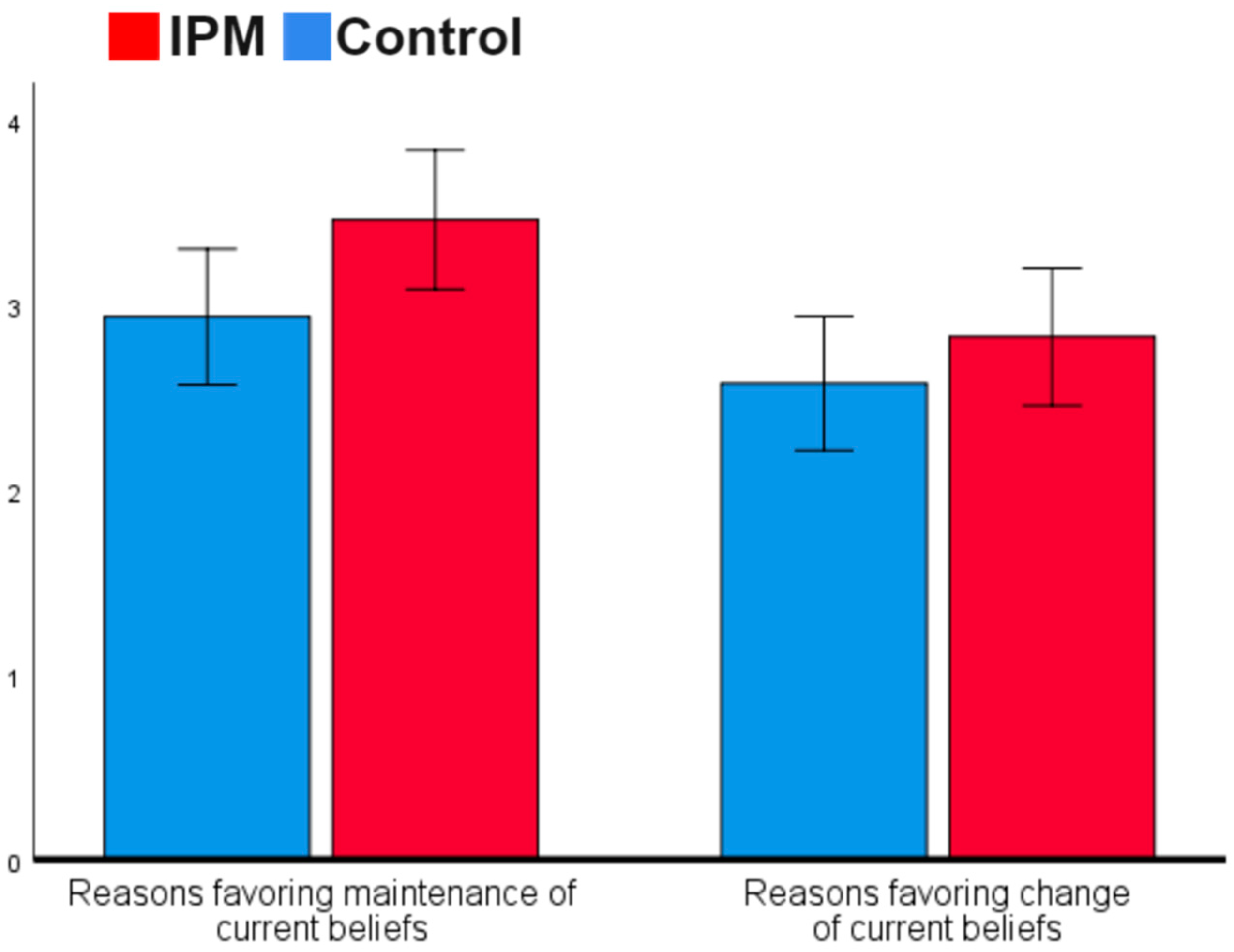

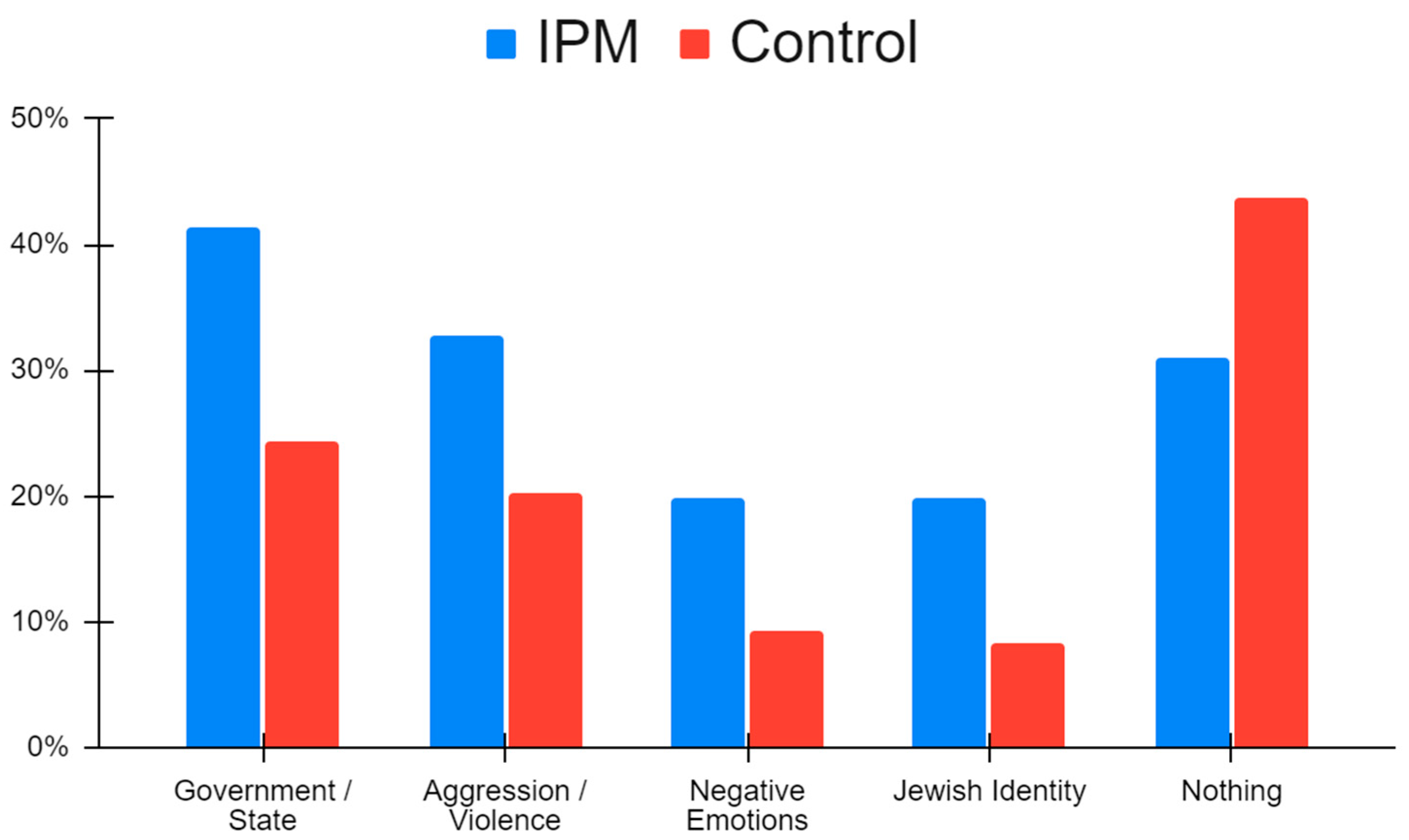

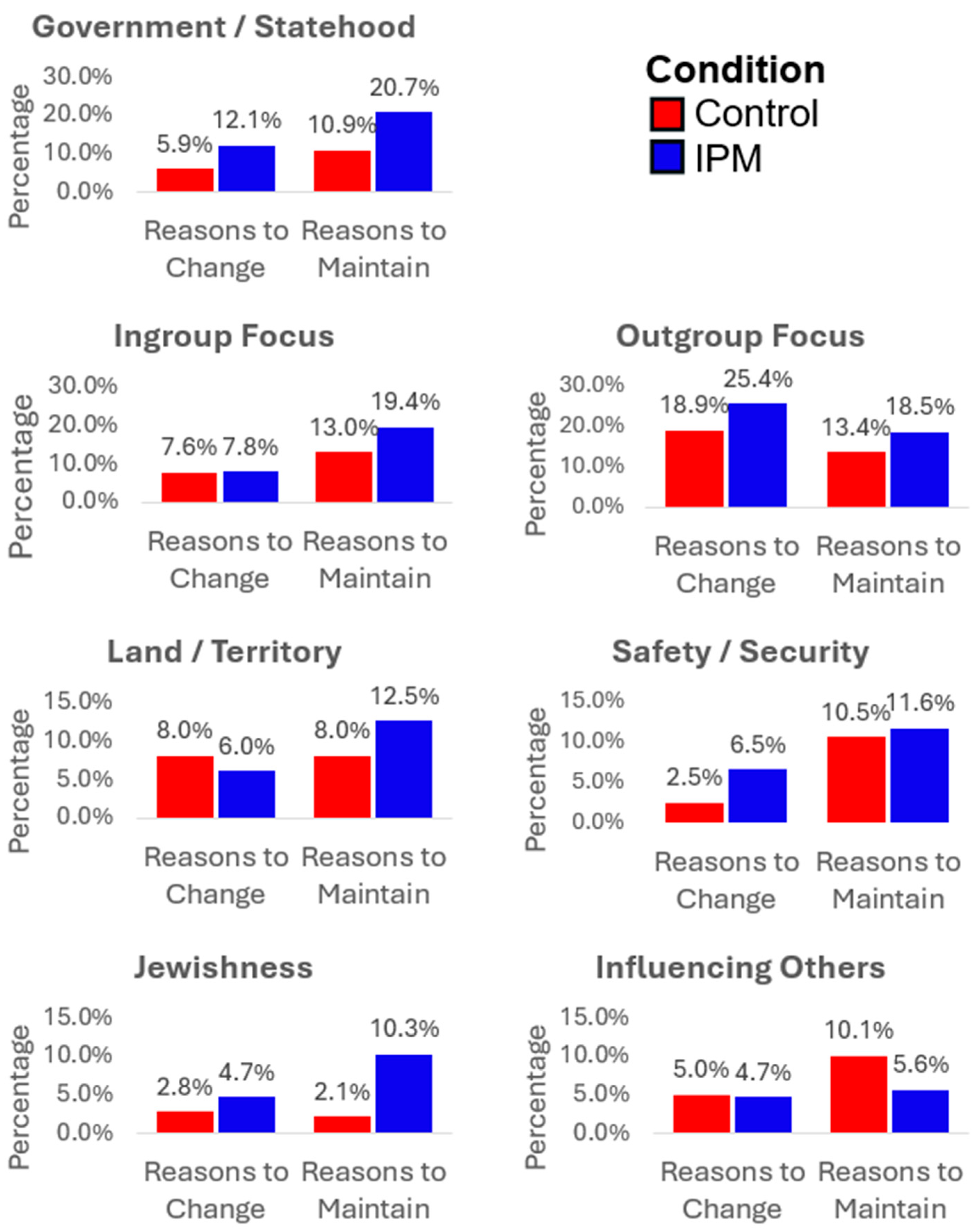

2.2.1. Assessing Impact of IPM-Based Intervention on Decisional Balance

2.2.2. Qualitative Analysis of Considerations in Decisional Balance Measure

2.3. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Procedure and Materials

- 1.

- The first segment, about 17 s long, presents the partially hidden figure and narrative-acknowledging quotes, and ends before revealing the figure, its identity or its context. This part is intended to normalize the conflict-supporting narrative and create identification with the hidden character.

- 2.

- The second segment, about 13 s long, begins with revealing the face of the figure and his identity as a French soldier who refers, in the previous quotes, to the French–Algerian war. It is followed by messages validating the normality of the narrative and its effectiveness in coping with the experiences of intractable conflicts. The first and second segments convey the acceptance element of the dialectic approach.

- 3.

- The third segment, about 13 s long, starts with the question “is there another way?”, followed by messages suggesting that an alternative narrative can lead to resolving the conflict, as in the case of the French–Algerian war that ended with a peace deal between the parties. The last segment completes the change element of the dialectic approach.

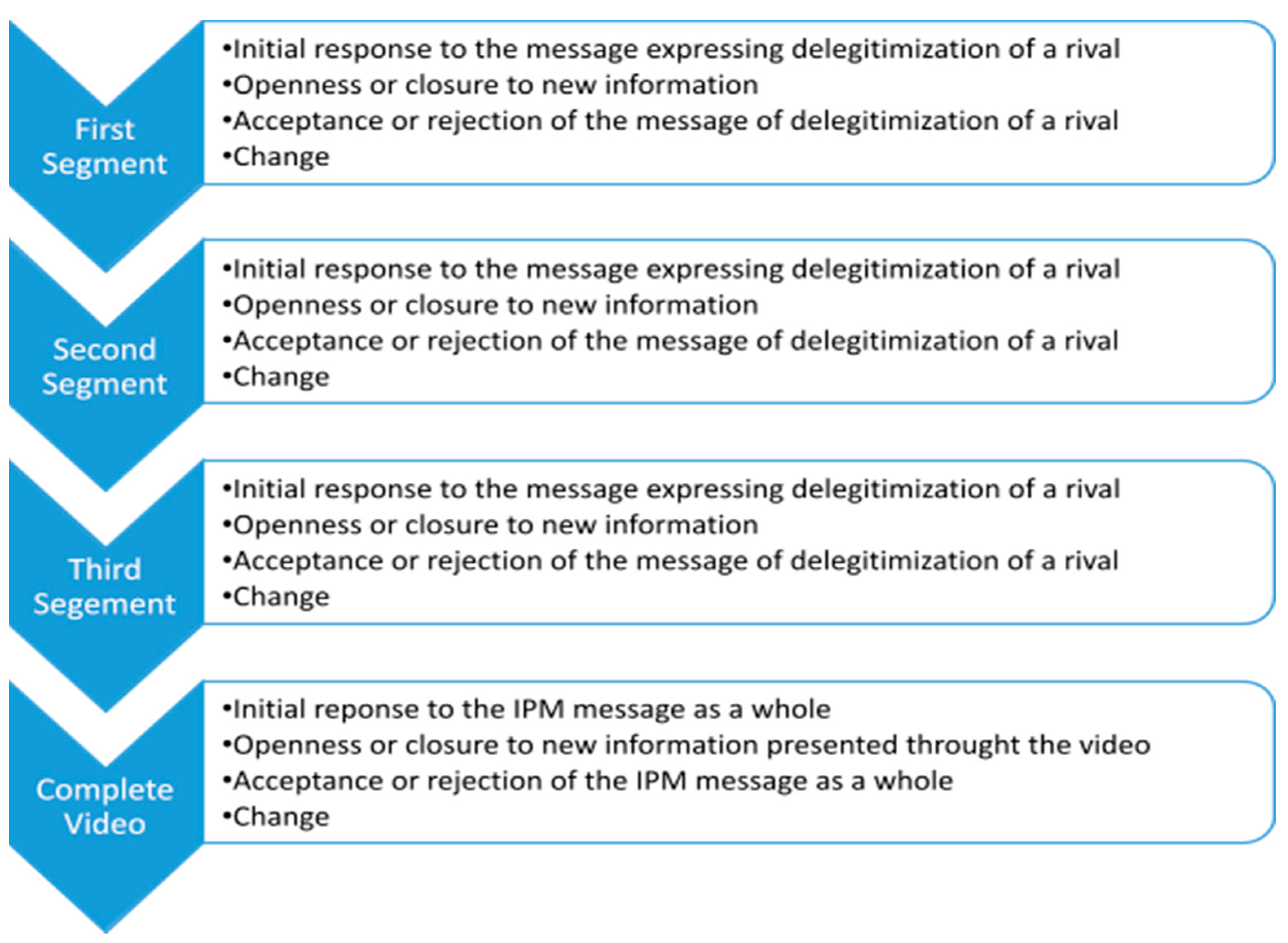

3.1.3. Analytic Framework

- 1.

- Initial Response to the message was examined both emotionally, i.e., how the participants felt after viewing the material, and cognitively, i.e., what thoughts arose following the viewing or their analytical processing of the information.

- 2.

- Openness or Closure to new information was assessed based on whether the participants were willing to consider and reflect on the new information presented to them, i.e., if they were open to listening to the information or chose to ignore it.

- 3.

- Acceptance or Rejection of the message was evaluated based on the degree of agreement with the message as stated by the participants, while also considering the level of interest, the way the information was processed, and the depth of engagement or immediate dismissal of the message.

- 4.

- Change occurring after viewing the segment or video was examined through the lens of the TTM. Specifically, we assessed whether the intervention prompted future-oriented thinking and whether the new information introduced new perspectives on viewing the conflict as resolvable, even if the interviewee has not yet committed to acting on this change in the near future, as described in the contemplation stage of the TTM.

3.2. Findings

3.2.1. First Segment

I have flashbacks of suicides and attacks, and also situations I know from the army, where you suspect someone and feel uncomfortable […] but it turns out that this person had a knife, and he could have murdered a family.

[…] during the last [conflict] operation, I’m not talking about the part in Gaza, but about what happened here inside the country, the trust relations were quite eroded, so there can be a certain degree, like in certain moments, there can be a certain degree of identification.

3.2.2. Second Segment

Maybe it makes me feel a bit more hopeful, because if it’s something that happens elsewhere and somehow in other places, they managed to resolve it in some way and achieve peace, then maybe our situation could be solvable too, and eventually, it will work out.

The exposure of the character made me see that this happens to everyone. I mean, everyone has a side, our side is good compared to your side, which is bad, but for me, the connotation immediately arose because it happens to them, I immediately associate it with what happens here, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Not all of them want to behave like beasts, some behave exactly the opposite, on the one hand. On the other hand, if we only look at the part that doesn’t want war, then we miss the part that behaves like beasts, so it’s natural but to a certain extent.

3.2.3. Third Segment

[…] a kind of hope, maybe each side can try to examine itself, do some self-reflection, think about how we can bridge the gap, maybe not in everything, but at least try to reach some common ground in some areas, and not see each other in such an extreme light as in the beginning.

I agree that there is an alternative, but I think the comparison between this war and another war is a bit strange [...] because France had France, and it was perceived as a foreign entity that came to take over Algeria, while in Israel, it’s more of a war. I wouldn’t say an existential war, but it’s closer to home than what happened there.

Now, when I see it as a whole, it’s like the hypocrisy, the emotion with which it’s painted and fawning, overshadows all the other feelings I had before because it really leads you to this place of ‘look at these terrible things that were said, look at these terrible things that were done, see, it doesn’t have to be like this, and conflicts can be resolved differently’ and I’m like: ‘enough already’. (Interviewee No. 23)

Yes, you can see optimism that conflict resolution can indeed happen, for example, at least in Israel, with countries that we don’t share a border with [...] [in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict] there is no optimism, there is pessimism and the thought that I won’t live to see it.

The third video, the short one, it presents a way of thinking, maybe trying to think differently, maybe trying to see how we can minimize this thinking, these words, these harsh things, look, it happened there, maybe it can happen in other places, maybe it’s a case study that can also help us, apply it to us.

3.2.4. The Complete Video

It made me think that the structure of the video, the way it starts with emotions like anger and strong, harsh words, but in the end, it kind of reaches a conclusion of acceptance, of the idea that things can be different, and that it is possible, and not something that hasn’t happened before.

I feel like someone understands me and empathizes with me, and along with that, at the end, after the message of ‘we understand your side’, there’s the idea that things can be different because it’s already happened somewhere else, and they’ve found a solution. It’s like connecting with the other person’s opinion and then asking them, ‘maybe you can ask yourself’—maybe something else is possible.

When I watch it from beginning to end, certain things become clearer to me. For instance, at the beginning, when they said ‘we had to call them human beasts, we had to say they were murderers’, to maintain the narrative that the enemy is evil, suddenly it became very clear to me.

It raises questions for me, like how they did it, what their way of doing it was, if there was a third party involved […] So many questions about how it happens, because ultimately, that’s also my hope—that it will happen. I think the video really gave me some understanding that there might be certain ways they did it, so maybe it also applies to us, maybe not, but we should definitely know these methods and explore them a bit.

Personally, it made me go through various emotions, from anger to firm agreement and amusement, and suddenly it made me change my thinking. I don’t know if ‘change’ is the right word, but it just made me look at it from a different angle... I think it made me think more that a solution might be possible. (Interviewee No. 17)

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosler, N.; Yakter, A. Peace Index—January 2024. Tel Aviv University. 2024. Available online: https://en-social-sciences.tau.ac.il/peaceindex/archive/2024-01 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Shikaki, K. Public Opinion Poll No. 92. Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Analysis. 2024. Available online: https://pcpsr.org/en/node/985 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Shikaki, K.; Sheindlin, D.; Rosler, N.; Yakter, A. The Palestine/Israel Pulse: A Joint Survey. Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Analysis and Tel Aviv University. 2024. Available online: https://www.pcpsr.org/en/node/989 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Bar-Tal, D.; Halperin, E. Socio-psychological barriers to peace making: An empirical examination within the Israeli Jewish society. J. Peace Res. 2011, 48, 637–651. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, E.; Hameiri, B.; Littman, R. (Eds.) Psychological Intergroup Interventions: Where We Are and Where We Go from Here. In Psychological Intergroup Interventions: Evidence-Based Approaches to Improve Intergroup Relations; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Čehajić-Clancy, S.; Halperin, E. Advancing research and practice of psychological intergroup interventions. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2024, 3, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosler, N.; Sharvit, K.; Hameiri, B.; Weiner-Blotner, O.; Idan, O.; Bar-Tal, D. The Informative Process Model as a new intervention for attitude change in intractable conflicts: Theory and empirical evidence. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 946410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Tal, D. Intractable Conflicts: Socio-Psychological Foundations and Dynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, P.T. Characteristics of protracted, intractable conflict: Toward the development of a metaframework-I. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 2003, 9, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriesberg, L. Intractable conflicts. Peace Rev. 1993, 5, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, H.C. Social-psychological dimensions of international conflict In Peacemaking in International Conflict: Methods and Techniques; Zartman, I.W., Ed.; United States Institute of Peace Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 61–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kriesberg, L. Nature dynamics phases of intractability In Grasping the Nettle: Analyzing Cases of Intractable Conflict; Crocker, C.A., Osler, H.F., Aall, P., Eds.; United States Institute of Peace Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Eidelson, R.J.; Eidelson, J.I. Dangerous ideas: Five beliefs that propel groups toward conflict. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garagozov, R.R. Narratives in conflict: A perspective. Dyn. Asymmetric Confl. 2012, 5, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjipavlou, M. The Cyprus conflict: Root causes and implications for peacebuilding. J. Peace Res. 2007, 44, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammack, P.L. Exploring the reproduction of conflict through narrative: Israeli youth motivated to participate in a coexistence program. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 2009, 15, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, Y. Narrative, memory and history education in divided Cyprus: A comparison of schoolbooks on the “History of Cyprus”. Hist. Mem. 2008, 20, 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosler, N.; Sharvit, K.; Bar-Tal, D. Perceptions of prolonged occupation as barriers to conflict resolution. Political Psychol. 2018, 39, 519–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, I.; McCauley, C. Threat, dehumanization, and support for retaliatory aggressive policies in asymmetric conflict. J. Confl. Resolut. 2008, 52, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollhardt, J.R.; Bilali, R. The role of inclusive and exclusive victim consciousness in predicting intergroup attitudes: Findings from Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC. Political Psychol. 2015, 36, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W. The Psychology of Closed Mindedness; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Webster, D.M. Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing”. Psychol. Rev. 1996, 103, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, J.B.; Flanders, J.L. Complexity management theory: Motivation for ideological rigidity and social conflict. Cortex 2002, 38, 429–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Hastings, S. Distortions of collective memory: How groups flatter deceive themselves. In Collective Memory of Political Events: Social Psychological Perspectives; Pennebaker, J.W., Paez, D., Rimé, B., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 277–293. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, S. Speaking of Violence: The Politics and Poetics of Narrative in Conflict Resolution; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal, D.; Hameiri, B. Interventions to change well-anchored attitudes in the context of intergroup conflict. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2020, 14, e12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Fielding, K.S. Attitude roots and Jiu Jitsu persuasion: Understanding and overcoming the motivated rejection of science. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ezer, I.; Rosler, N.; Sharvit, K.; Wiener-Blotner, O.; Bar-Tal, D.; Nasie, M.; Hameiri, B. From acceptance to change: The role of acceptance in the effectiveness of the Informative Process Model for conflict resolution. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S. Answering Survey Questions: The Measurement Meaning of Public Opinion In Political Judgment: Structure and Process; Lodge, M., McGraw, K.M., Eds.; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1995; pp. 249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, P.L. Measuring ambivalence to science. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1987, 24, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, K.; Broemer, P.; Diehl, M. Attitudinal ambivalence. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 11, 35–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.; Martinez, M. (Eds.) Ambivalence and the Structure of Political Opinion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, D.E.; Arkowitz, H. Ambivalence in Psychotherapy: Facilitating Readiness to Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, A. Resolving Patient Ambivalence: A Five Session Motivational Interviewing Intervention; Hollifield Associates: Princeton, WV, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.M.; Mauriello, L.M.; Sherman, K.J.; Harlow, L.; Silver, B.; Trubatch, J. Assessing readiness for advancing women scientists using the transtheoretical model. Sex Roles 2006, 54, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiu, C.; Li, Y.; He, W. Research on opinion polarization by big data analytics capabilities in online social networks. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, E.L.; Porat, R.; Clark, C.S.; Green, D.P. Prejudice reduction: Progress and challenges. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021, 72, 533–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Tal, D.; Halperin, E. Overcoming psychological barriers to peace process: The influence of instigating beliefs about losses In Prosocial Motives, Emotions and Behavior; Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 431–448. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.; Bury, M.; Campling, N.; Carter, S.; Garfied, S.; Newbould, J.; Rennie, T. A Review of the Use of the Health Belief Model (HBM), the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and the Trans-Theoretical Model (TTM) to Study and Predict Health Related Behaviour Change; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F.; Rossi, J.S.; Goldstein, M.G.; Marcus, B.H.; Rakowski, W.; Fiore, C.; Harlow, L.L.; Redding, C.A.; Rosenbloom, D.; et al. Stages of change and Decisional Balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994, 13, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, S.; Day, A.; Howells, K. The application of the transtheoretical model to offender populations: Some critical issues. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 2005, 10, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, E.M.; Doidge, M.; Aytur, S.; Wilson, R.S. Understanding farmers’ conservation behavior over time: A longitudinal application of the transtheoretical model of behavior change. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimolizzi-Jensen, C.J. Organizational change: Effect of motivational interviewing on readiness to change. J. Chang. Manag. 2018, 18, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Lu, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Dong, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, N.; Yu, F.; Wan, Q.; et al. The effect of transtheoretical model-lead intervention for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: A cluster randomized trial. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2020, 22, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, J.H.; Girvin, H. Stages of change: A critique. Behav. Modif. 2002, 26, 223–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnaughy, E.A.; Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. Stages of change in psychotherapy: Measurement and sample profiles. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 1983, 20, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicer, W.F.; Prochaska, J.O.; Fava, J.L.; Norman, G.J.; Redding, C.A. Smoking cessation and stress management: Applications of the Transtheoretical Model of behavior change. Homeostasis 1998, 38, 216–233. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leshem, O.; Halperin, E. Hoping for peace during protracted conflict: Citizens’ hope is based on inaccurate appraisals of their adversary’s hope for peace. J. Confl. Resolut. 2020, 64, 3–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods design—Principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseholm, E.; Fetters, M.D. Conceptual models to guide integration during analysis in convergent mixed methods studies. Methodol. Innov. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; An, B. Comparison of the Predictors of Smoking Cessation Plans between Adolescent Conventional Cigarette Smokers and E-Cigarette Smokers Using the Transtheoretical Model. Children 2024, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicer, W.F.; DiClemente, C.C.; Prochaska, J.O.; Brandenburg, N. Decisional balance measures for assessing and predicting smoking status. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, I.L.; Mann, L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, E. Emotions in Conflict: Inhibitors and Facilitators of Peace Making; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman, I.J.; Antonio, A.A.; Jose, P.E. Appraisal determinants of emotions: Constructing a more accurate and comprehensive theory. Cogn. Emot. 1996, 10, 241–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Ellsworth, P.C. Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarymowicz, M.; Bar-Tal, D. The dominance of fear over hope in the life of individuals and collectives. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, E.G. Emotion conflict: Why it is important to understand how emotions affect conflict how conflict affects emotions In The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Coleman, P.T., Deutsch, M., Marcus, E.C., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 283–309. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, N. Fear and Conflict Resolution: Theoretical Discussion and a Case Study from Israel; The Gildenhorn Institute for Israel Studies Research Papers; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, E.; Pliskin, R. Emotions and emotion regulation in intractable conflict: Studying emotional processes within a unique context. Adv. Political Psychol. 2015, 36, 119–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, J.R. Studies on anger and aggression: Implications for theories of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1983, 38, 1145–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackie, D.M.; Devos, T.; Smith, E.R. Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, E.; Russell, A.G.; Dweck, C.S.; Gross, J.J. Anger, hatred, and the quest for peace: Anger can be constructive in the absence of hatred. J. Confl. Resolut. 2011, 55, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifen Tagar, M.; Halperin, E.; Frederico, C. The positive effect of negative emotions in protracted conflict: The case of anger. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshem, O.A. Hope Amidst Conflict: Philosophical and Psychological Explorations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leshem, O.A. The pivotal role of the enemy in inducing hope for peace. Political Stud. 2019, 67, 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R. The Psychology of Hope: You Can Get There from Here; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C.R. (Ed.) Handbook of Hope: Theory, Measures, and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Staats, S.R.; Stassen, M.A. Hope: An affective cognition. Soc. Indic. Res. 1985, 17, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breznitz, S. The effect of hope on coping with stress. In Dynamics of Stress; Appley, M.H., Trumbull, R., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 295–306. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Chen, S.; Halperin, E.; Crisp, R.J.; Gross, J.J. Hope in the Middle East: Malleability beliefs, hope, and the willingness to compromise for peace. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2014, 5, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosler, N.; Cohen-Chen, S.; Halperin, E. The distinctive effects of empathy and hope in intractable conflicts. J. Confl. Resolut. 2017, 61, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Chen, S.; Crisp, R.J.; Halperin, E. Hope comes in many forms: Outgroup expressions of hope override low support and promote reconciliation in conflicts. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad-Strenger, J.; Saguy, T.; Halperin, E. Facilitating hope among the hopeless: The role of ideology and moral content in shaping reactions to internal criticism in the context of intractable conflict. Soc. Sci. Q. 2019, 100, 2425–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosler, N.; Hameiri, B.; Bar-Tal, D.; Or, M.S. Perceiving change on the other side of the conflict: A pathway to reconciliation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2023, 96, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammack, P.L.; Pilecki, A.; Caspi, N.; Strauss, A.A. Prevalence and correlates of delegitimization among Jewish Israeli adolescents. Peace Confl. 2011, 17, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, N.; Bar-Tal, D. The detrimental effects of delegitimization in intractable conflicts: The Israeli-Palestinian case. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2007, 31, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N.; Loughnan, S. Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kteily, N.; Bruneau, E.; Waytz, A.; Cotterill, S. The ascent of man: Theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 901–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, E. The roots of evil: Social conditions, culture, personality, and basic human needs. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 3, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tal, D.; Hammack, P.L. Conflict, Delegitimization, and Violence. In The Oxford Handbook of Intergroup Conflict; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv. Res. 1999, 34, 1189–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet, A.K.; Zauszniewski, J.A. Methodological triangulation: An approach to understanding data. Nurse Res. 2012, 20, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act in Sociology: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods; Aldine: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, L. AntConc: Design and development of a freeware corpus analysis toolkit for the technical writing classroom. In Proceedings of the IPCC 2005: International Professional Communication Conference, Limerick, Ireland, 10–13 July 2005; pp. 729–737. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, N. Containing the duality: Leadership in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. In The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: A Social Psychology Perspective; Sharvit, K., Halperin, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume II, pp. 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P.G. Toward a transtheoretical model of interprofessional education: Stages, processes and forces supporting institutional change. J. Interprofessional Care 2013, 27, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, M.; Yun, J. Public advertising design strategies to promote power-saving behavior. Arch. Des. Res. 2017, 30, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ali, S.; Akbar, A.; Rasool, F. Determining the influencing factors of biogas technology adoption intention in Pakistan: The moderating role of social media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.J. Applying behavior theories to financial behavior. In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelili, B. (Ed.) Conflict Resolution and Ontological Security: Peace Anxieties; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, N.; Abi-Ghannam, G.; Saab, R.; Albzour, M.; Zebian, Y.; Adams, G. Turning the lens in the study of precarity: On experimental social psychology’s acquiescence to the settler-colonial status quo in historic Palestine. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 62, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhana, N.N. Group identity and power asymmetry in reconciliation processes: The Israeli-Palestinian case. Peace Confl. 2004, 10, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. ACT Made Simple: An Easy-to-Read Primer on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosler, N.; Wiener-Blotner, O.; Heskiau Micheles, O.; Sharvit, K. Understanding Reactions to Informative Process Model Interventions: Ambivalence as a Mechanism of Change. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121152

Rosler N, Wiener-Blotner O, Heskiau Micheles O, Sharvit K. Understanding Reactions to Informative Process Model Interventions: Ambivalence as a Mechanism of Change. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121152

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosler, Nimrod, Ori Wiener-Blotner, Orel Heskiau Micheles, and Keren Sharvit. 2024. "Understanding Reactions to Informative Process Model Interventions: Ambivalence as a Mechanism of Change" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 12: 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121152

APA StyleRosler, N., Wiener-Blotner, O., Heskiau Micheles, O., & Sharvit, K. (2024). Understanding Reactions to Informative Process Model Interventions: Ambivalence as a Mechanism of Change. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14121152