The Impact of Family Wealth on Asset Return: A Moderated Chain Median Model Partially Explaining Wealth Inequality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Propositions

2.1. Applying Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory to Explanation of Relationship Between Family Wealth, Risk Preference, Asset-Holding Period, and Asset Return

2.2. Family Wealth and Disposition Effect

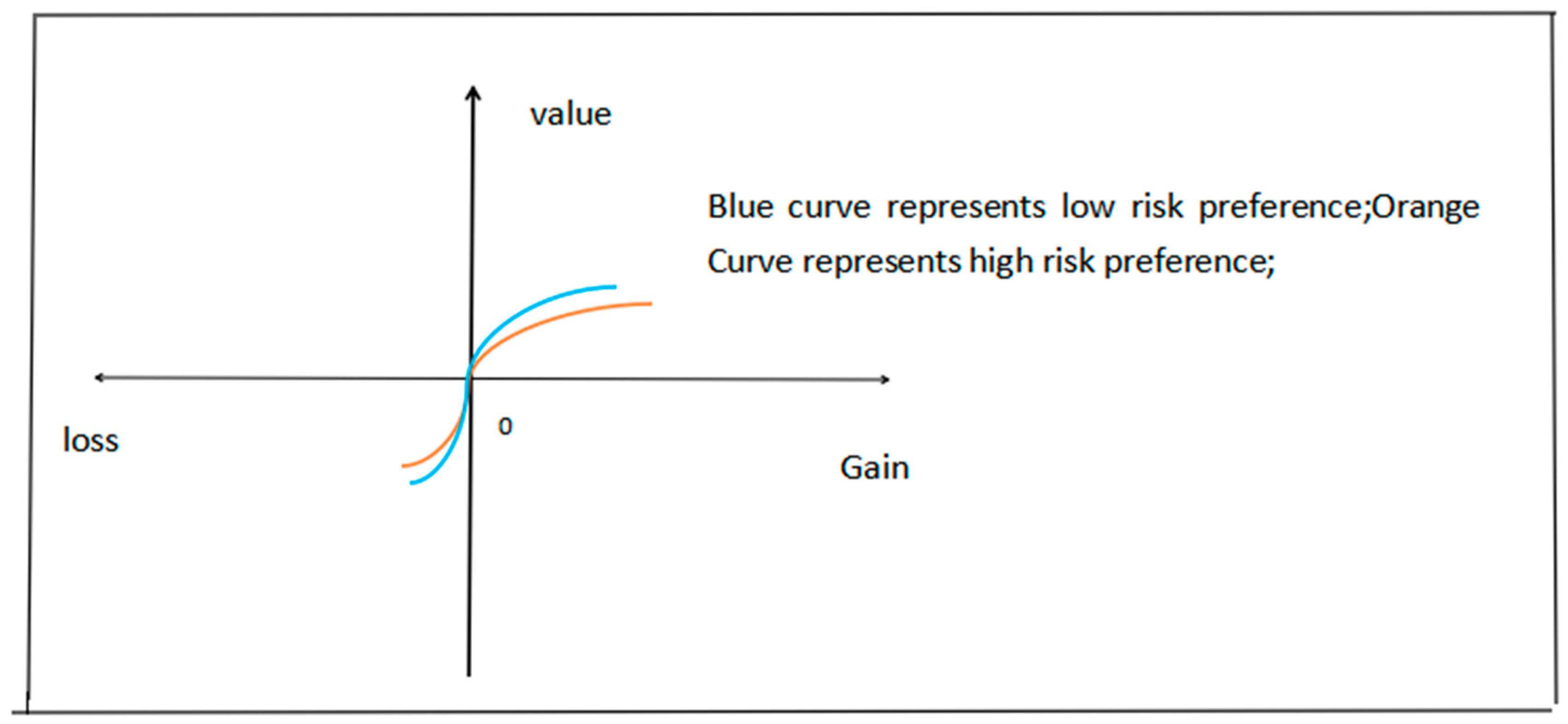

2.3. Risk Preference and Disposition Effect: Prospect Theory Perspective

2.4. Deposition Effect and Asset Return

2.5. The Moderating Role of Financial Literacy

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions and Discussion

4.1. Summary of Proposed Model

4.2. Theoretical Implication

4.3. Practical Implication

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zucman, G. Global wealth inequality. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2019, 11, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, F.T.; Schoeni, R.F. How wealth inequality shapes our future. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Keister, L.A.; Moller, S. Wealth inequality in the United States. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubmer, J.; Krusell, P.; Smith Jr, A.A. Sources of US wealth inequality: Past, present, and future. NBER Macroecon. Annu. 2021, 35, 391–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, L.; Calvet, L.E.; Sodini, P. Rich pickings? Risk, return, and skill in household wealth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 2703–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagereng, A.; Guiso, L.; Malacrino, D.; Pistaferri, L. Heterogeneity and persistence in returns to wealth. Econometrica 2020, 88, 115–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.; Zhu, N. Up Close and Personal: An Individual Level Analysis of the Disposition Effect; Yale School of Management: New Haven, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ingale, K.K.; Paluri, R.A. Financial literacy and financial behaviour: A bibliometric analysis. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2022, 14, 130–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. J. Econ. Lit. 2014, 52, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, C.A.; Woodyard, A. Financial knowledge and best practice behavior. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2011, 22, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij, M.; Lusardi, A.; Alessie, R. Financial literacy and stock market participation. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 101, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamori, N.; Ueyama, H. Financial literacy and low stock market participation of Japanese households. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 44, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrman, J.R.; Mitchell, O.S.; Soo, C.; Bravo, D. Financial Literacy, Schooling, and Wealth Accumulation. In NBER Working Paper.2010, No. 16452; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sekita, S.; Kakkar, V.; Ogaki, M. Wealth, financial literacy and behavioral biases in Japan: The effects of various types of financial literacy. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2022, 64, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Neveu, J.P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, R.; Frey, R.; Richter, D.; Schupp, J.; Hertwig, R. Risk preference: A view from psychology. J. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 32, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Li, H.; Wang, Q. Risk tolerance and household wealth--Evidence from Chinese households. Econ. Model. 2021, 94, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alles, L.; Murray, L. Investment performance and holding periods: An investigation of the major UK asset classes. J. Asset Manag. 2009, 10, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanouli, A.; Hofmans, J. A resource-based perspective on organizational citizenship and counterproductive work behavior: The role of vitality and core self-evaluations. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 1435–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laopodis, N.T. Understanding Investments: Theories and Strategies; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barberis, N.; Xiong, W. What drives the disposition effect? An analysis of a long-standing preference-based explanation. J. Financ. 2009, 64, 751–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.M.; Lee, Y.T.; Liu, Y.J.; Odean, T. Is the aggregate investor reluctant to realise losses? Evidence from Taiwan. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2007, 13, 423–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.Y.; Lee, C.I.; Lin, C.H. An examination of the relationship between the disposition effect and gender, age, the traded security, and bull–bear market conditions. J. Empir. Financ. 2013, 21, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genesove, D.; Mayer, C. Loss aversion and seller behavior: Evidence from the housing market. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 1233–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincapié-Salazar, J.; Agudelo, D.A. Is the disposition effect in bonds as strong as in stocks? Evidence from an emerging market. Glob. Financ. J. 2020, 46, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N.C. Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: A review and assessment. J. Econ. Perspect. 2013, 27, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikogiannopoulou, A.; Papakonstantinou, F. History-dependent risk preferences: Evidence from individual choices and implications for the disposition effect. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 3674–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkhoff, L.; Sarno, L.; Schmeling, M.; Schrimpf, A. Currency momentum strategies. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 106, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beracha, E.; Skiba, H. Momentum in residential real estate. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2011, 43, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asness, C.S.; Moskowitz, T.J.; Pedersen, L.H. Value and momentum everywhere. J. Financ. 2013, 68, 929–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seru, A.; Shumway, T.; Stoffman, N. Learning by trading. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 705–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, H.; Eom, Y. The disposition effect and investment performance in the futures market. J. Futures Mark. Futures Options Other Deriv. Prod. 2009, 29, 496–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennah, H Launch of the OECD/INFE 2020 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy. 2020. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/3808900/launch-of-the-oecdinfe-2020-international-survey-of-adult-financial-literacy/4614816/ (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Mandell, L.; Klein, L.S. The impact of financial literacy education on subsequent financial behavior. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2009, 20, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso, L.; Viviano, E. How much can financial literacy help? Rev. Financ. 2015, 19, 1347–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.K.; Kumar, S.; Goyal, N.; Gaur, V. How financial literacy and demographic variables relate to behavioral biases. Manag. Financ. 2019, 45, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weixiang, S.; Qamruzzaman, M.; Rui, W.; Kler, R. An empirical assessment of financial literacy and behavioral biases on investment decision: Fresh evidence from small investor perception. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 977444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.R.; Harvey, C.R.; Huang, H. Investor competence, trading frequency, and home bias. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.; Baron, A. Managing Performance: Performance Management in Action; CIPD Publishing: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aristei, D.; Gallo, M. Assessing gender gaps in financial knowledge and self-confidence: Evidence from international data. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 46, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupák, A.; Fessler, P.; Schneebaum, A. Gender differences in risky asset behavior: The importance of self-confidence and financial literacy. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 42, 101880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J. Financial education and financial literacy by income and education groups. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2019, 30, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, T.; Menkhoff, L. Does financial education impact financial literacy and financial behavior, and if so, when? World Bank Econ. Rev. 2017, 31, 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hira, T.K. Promoting sustainable financial behaviour: Implications for education and research. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Maurer, R.; Mitchell, O.S. Choosing a financial advisor: When and how to delegate. In Financial Decision Making and Retirement Security in an Aging World; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 86–95. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tu, T. The Impact of Family Wealth on Asset Return: A Moderated Chain Median Model Partially Explaining Wealth Inequality. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111048

Tu T. The Impact of Family Wealth on Asset Return: A Moderated Chain Median Model Partially Explaining Wealth Inequality. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(11):1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111048

Chicago/Turabian StyleTu, Tianye. 2024. "The Impact of Family Wealth on Asset Return: A Moderated Chain Median Model Partially Explaining Wealth Inequality" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 11: 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111048

APA StyleTu, T. (2024). The Impact of Family Wealth on Asset Return: A Moderated Chain Median Model Partially Explaining Wealth Inequality. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111048