Perfectionism and Adolescent Athletes’ Burnout: The Serial Mediation of Motivation and Coping Style

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Perfectionism and Burnout

1.2. Perfectionism, Motivation, and Burnout

1.3. Perfectionism, Coping Style, and Burnout

1.4. Perfectionism, Motivation, Coping Style, and Burnout

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Athlete Burnout

2.2.2. Perfectionism

2.2.3. Motivation

2.2.4. Coping Styles

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.3. Pathway Tests

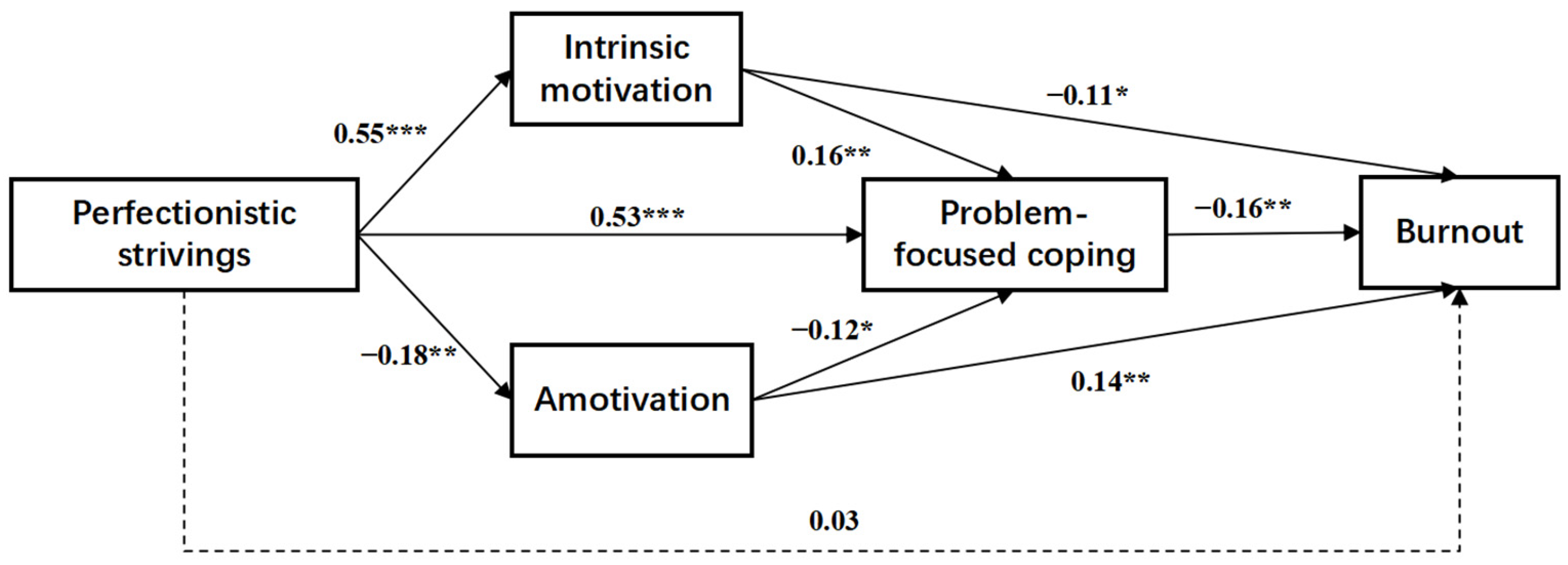

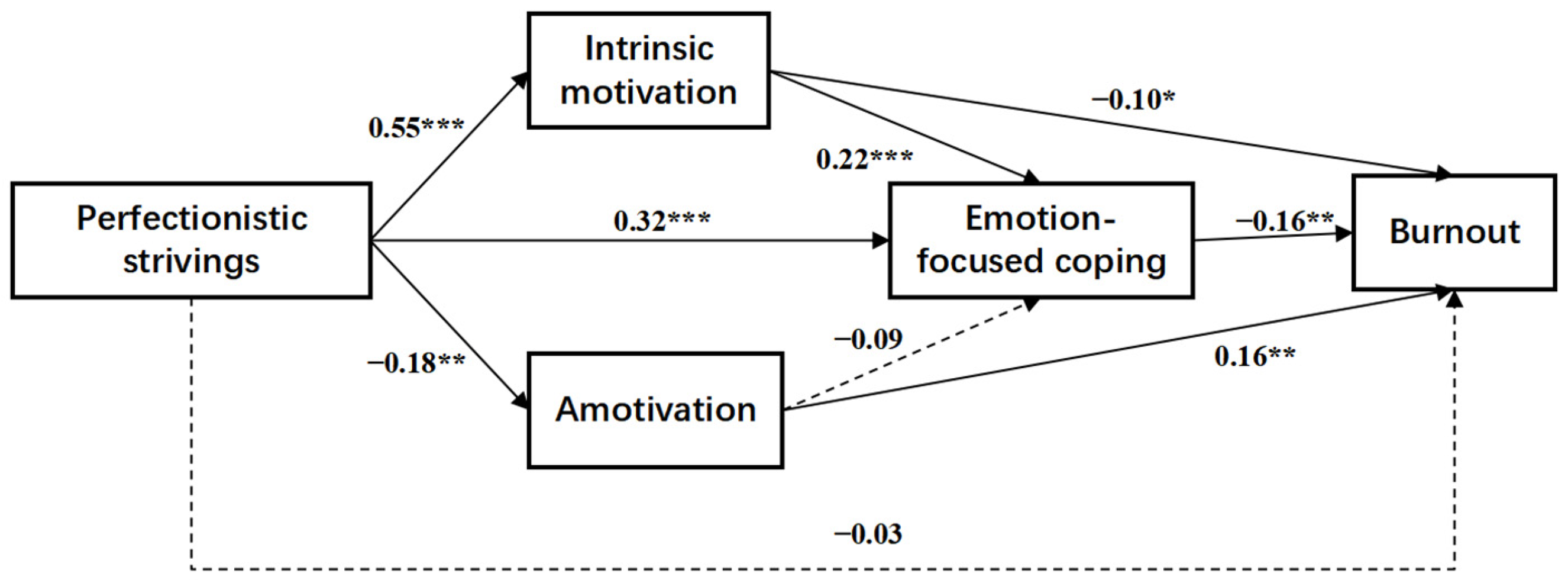

3.3.1. Perfectionistic Strivings and Burnout

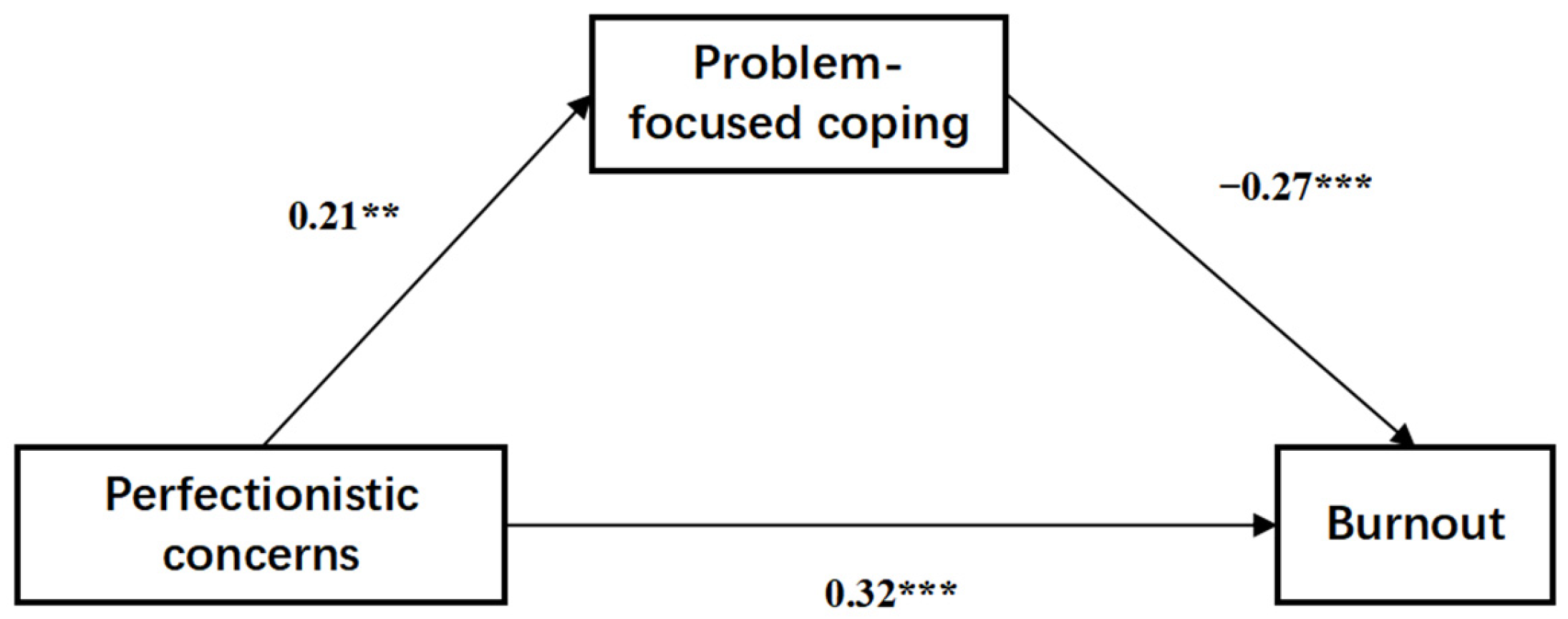

3.3.2. Perfectionistic Concerns and Burnout

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship Between Perfectionism and Burnout

4.2. The Mediation Role of Motivation

4.3. The Mediation Role of Coping Styles

4.4. The Serial Mediation Role of Motivation and Coping Style

4.5. Limitations and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raedeke, T.D.; Smith, A.L. Development and Preliminary Validation of an Athlete Burnout Measure. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2001, 23, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigan, D.J.; Olsson, L.F.; Hill, A.P.; Curran, T. Athlete Burnout Symptoms Are Increasing: A Cross-Temporal Meta-Analysis of Average Levels from 1997 to 2019. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 44, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, G.; Eklund, R.C.; Boiangin, N. (Eds.) Handbook of Sport Psychology, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-119-56808-7. [Google Scholar]

- Isoard-Gautheur, S.; Guillet-Descas, E.; Gustafsson, H. Athlete Burnout and the Risk of Dropout Among Young Elite Handball Players. Sport Psychol. 2016, 30, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, D.; Dieffenbach, K.; Moffett, A. Psychological Characteristics and Their Development in Olympic Champions. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2002, 14, 172–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, P.R.; Hill, A.P. Perfectionism and Athlete Burnout in Junior Elite Athletes: The Mediating Role of Motivation Regulations. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2012, 6, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Edmunds, J.; Duda, J.L. Understanding the Coping Process from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 14, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, A.; Michou, A. Perfectionism, Self-Determined Motivation, and Coping among Adolescent Athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.O.; Marten, P.; Lahart, C.; Rosenblate, R. The Dimensions of Perfectionism. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1990, 14, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P.L.; Flett, G.L. Perfectionism in the Self and Social Contexts: Conceptualization, Assessment, and Association with Psychopathology. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Otto, K. Positive Conceptions of Perfectionism: Approaches, Evidence, Challenges. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotwals, J.K.; Dunn, J.G.H. A Multi-Method Multi-Analytic Approach to Establishing Internal Construct Validity Evidence: The Sport Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale 2. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2009, 13, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, D.M.; Blankstein, K.R.; Halsall, J.; Williams, M.; Winkworth, G. The Relation between Perfectionism and Distress: Hassles, Coping, and Perceived Social Support as Mediators and Moderators. J. Couns. Psychol. 2000, 47, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, P.; Thompson, A. Testing a 2×2 Model of Dispositional Perfectionism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Stoeber, F.S. Domains of Perfectionism: Prevalence and Relationships with Perfectionism, Gender, Age, and Satisfaction with Life. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Stoeber, J.; Passfield, L. Perfectionism and Burnout in Junior Athletes: A Three-Month Longitudinal Study. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Květon, P.; Jelínek, M.; Burešová, I. The Role of Perfectionism in Predicting Athlete Burnout, Training Distress, and Sports Performance: A Short-Term and Long-Term Longitudinal Perspective. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 1969–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. Perfectionism and Burnout in Junior Soccer Players: A Test of the 2 × 2 Model of Dispositional Perfectionism. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 35, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Curran, T. Multidimensional Perfectionism and Burnout: A Meta-Analysis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 20, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Hall, H.K.; Appleton, P.R.; Kozub, S.A. Perfectionism and Burnout in Junior Elite Soccer Players: The Mediating Influence of Unconditional Self-Acceptance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 630–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, P. Self-Determined Motivation as a Predictor of Burnout Among College Athietes. Sport Psychol. 2013, 27, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cresswell, S.L.; Eklund, R.C. Motivation and Burnout among Top Amateur Rugby Players. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wang, C.K.J.; Pyun, D.Y.; Kee, Y.H. Burnout and Its Relations with Basic Psychological Needs and Motivation among Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodger, K.; Gorely, T.; Lavallee, D.; Harwood, C. Burnout in Sport: A Systematic Review. Sport Psychol. 2007, 21, 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıkabak, M.; Sarı, I.; Kolayiş, H.; Toros, T. Perfectionism and Motivation in Athletes: Negative Effect of Maladaptive Perfectionism on Motivation. In Proceedings of the Prague International Conference 27, Prague, Czech Republic, 6–9 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barcza-Renner, K.; Eklund, R.C.; Morin, A.J.; Habeeb, C.M. Controlling Coaching Behaviors and Athlete Burnout: Investigating the Mediating Roles of Perfectionism and Motivation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazanis, R.S. Stress and Emotion, a New Synthesis. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 1999, 6, 410–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. An Analysis of Coping in a Middle-Aged Community Sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1980, 21, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Park, Y.M.; Ying, J.Y.; Kim, B.; Noh, H.; Lee, S.M. Relationships between Coping Strategies and Burnout Symptoms: A Meta-Analytic Approach. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2014, 45, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, P.; Antl, S. Athletes’ Broad Dimensions of Dispositional Perfectionism: Examining Changes in Life Satisfaction and the Mediating Role of Sport-Related Motivation and Coping. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, J.R.N.; Oliveira, L.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Ferreira, L.; Vieira, L.; Freire, G.; Silva, A.; de Moraes, J.F.; Vieira, J. Perfectionism Traits and Coping Strategies in Soccer: A Study on Athletes’ Training Environment. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. The Relationship between Maladaptive Perfectionism with Burnout: Testing Mediating Effect of Emotion-Focused Coping. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, Z.-J.; Chi, H.-Y.; Liu, J.; Hager, M.J. The Mediating Role of Coping in the Relationship between Subtypes of Perfectionism and Job Burnout: A Test of the 2×2 Model of Perfectionism with Employees in China. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 58, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacewicz, C.E.; Gotwals, J.K.; Blanton, J.E. Perfectionism, Coping, and Burnout among Intercollegiate Varsity Athletes: A Person-Oriented Investigation of Group Differences and Mediation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Hall, H.K.; Appleton, P.R. Perfectionism and Athlete Burnout in Junior Elite Athletes: The Mediating Role of Coping Tendencies. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.E.; Gaudreau, P.; Blanchard, C.M. Self-Determination, Coping, and Goal Attainment in Sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2004, 26, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, G.; Hill, A.; Hall, H.; Curran, T. Perfectionism and Junior Athlete Burnout: The Mediating Role of Autonomous and Controlled Motivation. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2013, 2, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.W.; Mao, Z.X. Handbook of Psychological Scales for Sport Sciences; Peking Sport University Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.G.; Guo, Y.J. Correlation between kinetic fatigue, social support and mental health with respect to excellent athletes. J. Phys. Educ. 2007, 5, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, W.J.; Mao, Z.X.; Zi, F. Measurement and application of perfectionism personality traits in Chinese college athletes. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 5, 420–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.G.H.; Dunn, J.C.; Syrotuik, D.G. Relationship between Multidimensional Perfectionism and Goal Orientations in Sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2002, 24, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Lu, G.; Chen, S.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Liang, S.; Chen, C. The Effect of Perfectionism on Relative Deprivation among Nursing Students: The Role of Interpersonal Sensitivity and Resilience. Psychol. Sch. 2023, 61, 1360–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, F.; Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C. On the Assessment of Situational Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motiv. Emot. 2000, 24, 175–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.G.; Si, G.Y.; Li, Q.Z.; Liu, H. Development and Preliminary Test of Coping Scale for Chinese Athletes. Chin. J. Sports Med. 2004, 23, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Pearson/Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-205-45938-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-203-77158-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gnilka, P.; McLaulin, S.; Ashby, J.; Allen, M. Coping Resources As Mediators Of Multidimensional Perfectionism And Burnout. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2017, 69, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, D.A.; Lovibond, P.F.; Gaston, J.E. Relationship between Perfectionism and Emotional Symptoms in an Adolescent Sample. Aust. J. Psychol. 2000, 52, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozental, A. Beyond Perfect? A Case Illustration of Working with Perfectionism Using Cognitive Behavior Therapy. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 2041–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasalle, M.; Hess, U. A Motivational Approach to Perfectionism and Striving for Excellence: Development of a New Continuum-Based Scale for Post-Secondary Students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1022462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, R.B.; Herring, M.P.; Campbell, M.J. Associations Between Motivation and Mental Health in Sport: A Test of the Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquelon, P.; Vallerand, R.J.; Grouzet, F.M.E.; Cardinal, G. Perfectionism, Academic Motivation, and Psychological Adjustment: An Integrative Model. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atienza, F.L.; Castillo, I.; Appleton, P.R.; Balaguer, I. Examining the Mediating Role of Motivation in the Relationship between Multidimensional Perfectionism and Well- and Ill-Being in Vocational Dancers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Rumbold, J.L.; Gerber, M.; Nicholls, A.R. Coping Tendencies and Changes in Athlete Burnout over Time. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 48, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese-Bjornstal, D.M. Psychology and Socioculture Affect Injury Risk, Response, and Recovery in High-intensity Athletes: A Consensus Statement. Scand. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogoma, S. Problem-Focused Coping Controls Burnout in Medical Students: The Case of a Selected Medical School in Kenya. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2020, 8, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A.; Mitchell, M.A. Bias in Cross-Sectional Analyses of Longitudinal Mediation: Partial and Complete Mediation under an Autoregressive Model. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 816–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Athlete burnout | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.86 |

| Perfectionistic strivings | −0.39 | 0.53 | 0.88 |

| Perfectionistic concerns | 0.05 | −0.43 | 0.87 |

| Intrinsic motivation | −0.79 | 0.30 | 0.88 |

| Amotivation (without an item) | −0.04 | −0.45 | 0.76 |

| Problem-focused coping | −0.30 | 0.14 | 0.87 |

| Emotion-focused coping | −0.56 | 0.32 | 0.87 |

| Variable | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Athlete burnout | 2.34 ± 0.58 | - | ||||||

| 2. Perfectionistic strivings | 3.82 ± 0.75 | −0.201 * | - | |||||

| 3. Perfectionistic concerns | 3.12 ± 0.56 | 0.310 ** | 0.495 ** | - | ||||

| 4. Intrinsic motivation | 4.02 ± 0.90 | −0.272 ** | 0.462 ** | 0.110 | - | |||

| 5. Amotivation | 2.06 ± 0.85 | 0.331 ** | −0.305 ** | −0.010 | −0.363 ** | - | ||

| 6. Problem-focused coping | 3.76 ± 0.79 | −0.305 ** | 0.607 ** | 0.149 * | 0.433 ** | −0.353 ** | - | |

| 7. Emotion-focused coping | 3.81 ± 0.79 | −0.293 ** | 0.425 ** | 0.092 | 0.392 ** | −0.243 ** | 0.643 ** | - |

| Pathways | Effect | SE | 95%CI (LL, UL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total effect | −0.156 | 0.049 | (−0.252, −0.060) |

| 2 Direct effects | 0.029 | 0.061 | (−0.091, 0.149) |

| 3 Total indirect effects | −0.185 | 0.047 | (−0.281, −0.098) |

| 4 Perfectionistic strivings → intrinsic motivation → athlete burnout | −0.060 | 0.024 | (−0.112, −0.016) |

| 5 Perfectionistic strivings → amotivation → athlete burnout | −0.025 | 0.012 | (−0.051, −0.004) |

| 6 Perfectionistic strivings → problem-focused coping → athlete burnout | −0.083 | 0.033 | (−0.153, −0.024) |

| 7 Perfectionistic strivings → intrinsic motivation → problem-focused coping → athlete burnout | −0.014 | 0.007 | (−0.030, −0.002) |

| 8 Perfectionistic strivings → amotivation → problem-focused coping → athlete burnout | −0.003 | 0.003 | (−0.010, 0.000) |

| Pathways | Effect | SE | 95%CI (LL, UL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total effect | −0.156 | 0.049 | (−0.252, −0.060) |

| 2 Direct effects | −0.004 | 0.055 | (−0.112, 0.105) |

| 3 Total indirect effects | −0.152 | 0.035 | (−0.226, −0.086) |

| 4 Perfectionistic strivings → intrinsic motivation → athlete burnout | −0.056 | 0.026 | (−0.112, −0.011) |

| 5 Perfectionistic strivings → amotivation → athlete burnout | −0.028 | 0.013 | (−0.055, −0.005) |

| 6 Perfectionistic strivings → emotion-focused coping → athlete burnout | −0.050 | 0.019 | (−0.090, −0.017) |

| 7 Perfectionistic strivings → intrinsic motivation → emotion-focused coping → athlete burnout | −0.019 | 0.008 | (−0.037, −0.005) |

| 8 Perfectionistic strivings → amotivation → emotion-focused coping → athlete burnout | −0.003 | 0.002 | (−0.005, 0.006) |

| Pathways | Effect | SE | 95%CI (LL, UL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total effect | 0.322 | 0.064 | (0.197, 0.448) |

| 2 Direct effects | 0.379 | 0.060 | (0.261, 0.497) |

| 3 Perfectionistic concerns → problem-focused coping → athlete burnout | −0.056 | 0.027 | (−0.113, −0.008) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, A.; Luo, X.; Qiu, X.; Lu, C. Perfectionism and Adolescent Athletes’ Burnout: The Serial Mediation of Motivation and Coping Style. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111011

Xu A, Luo X, Qiu X, Lu C. Perfectionism and Adolescent Athletes’ Burnout: The Serial Mediation of Motivation and Coping Style. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(11):1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111011

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Aiai, Xiaobing Luo, Xueqing Qiu, and Changfen Lu. 2024. "Perfectionism and Adolescent Athletes’ Burnout: The Serial Mediation of Motivation and Coping Style" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 11: 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111011

APA StyleXu, A., Luo, X., Qiu, X., & Lu, C. (2024). Perfectionism and Adolescent Athletes’ Burnout: The Serial Mediation of Motivation and Coping Style. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1011. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111011