How Does Perceived Social Support Impact Mental Health and Creative Tendencies Among Chinese Senior High School Students?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. Perceived Social Support, Mental Health Problems, and Creative Tendencies

2.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem

2.3. The Moderating Role of Perceived Stress

2.4. Moderated Mediation Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Perceived Social Support Scale

3.2.2. Perceived Stress Scale

3.2.3. Self-Esteem Scale

3.2.4. Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90)

3.2.5. Adolescents’ Creative Tendencies Questionnaire

3.2.6. Control Variables

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test and Correlation Analysis

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

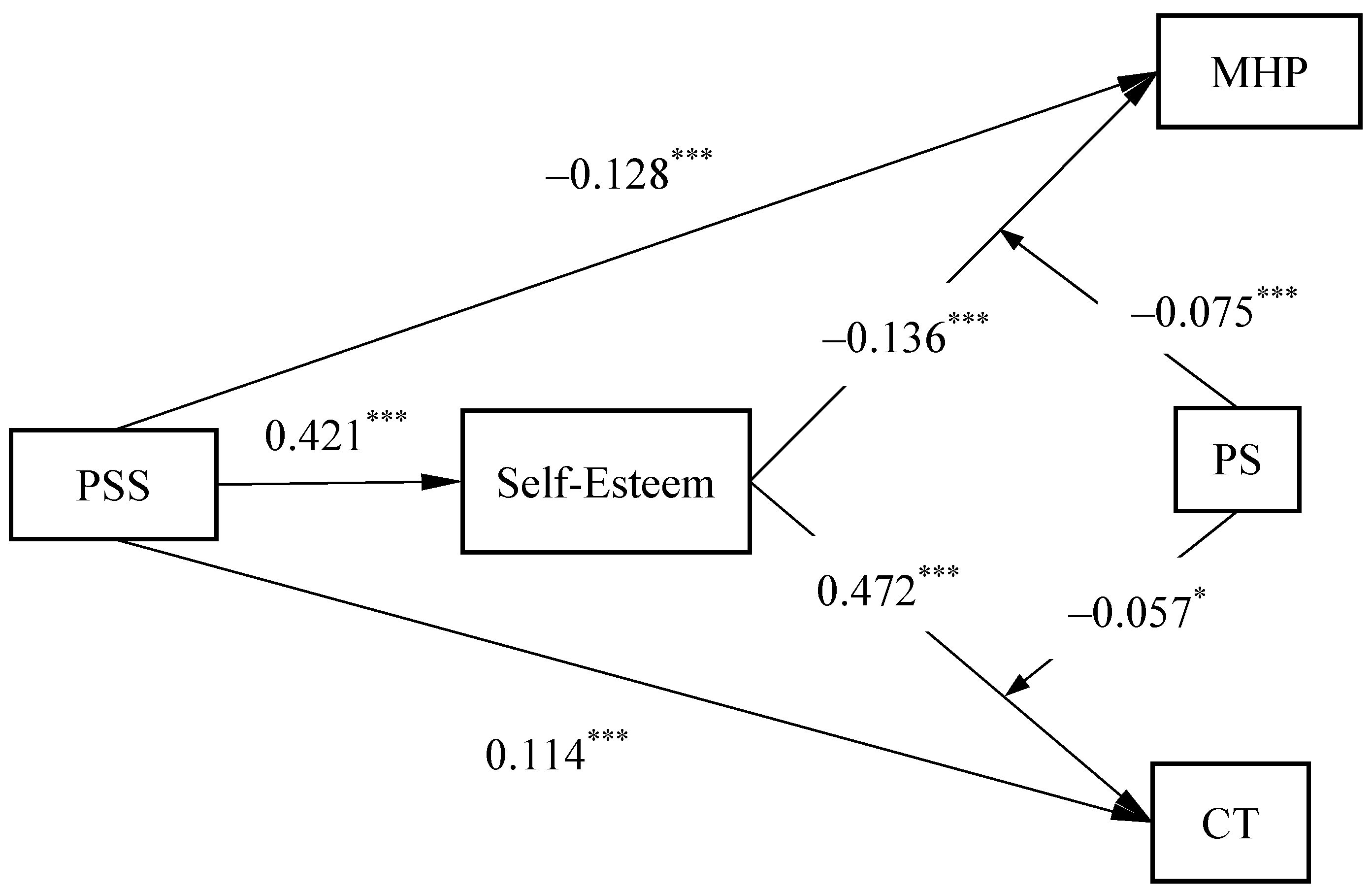

4.2.1. Direct Effect Test

4.2.2. Mediating Effect Test

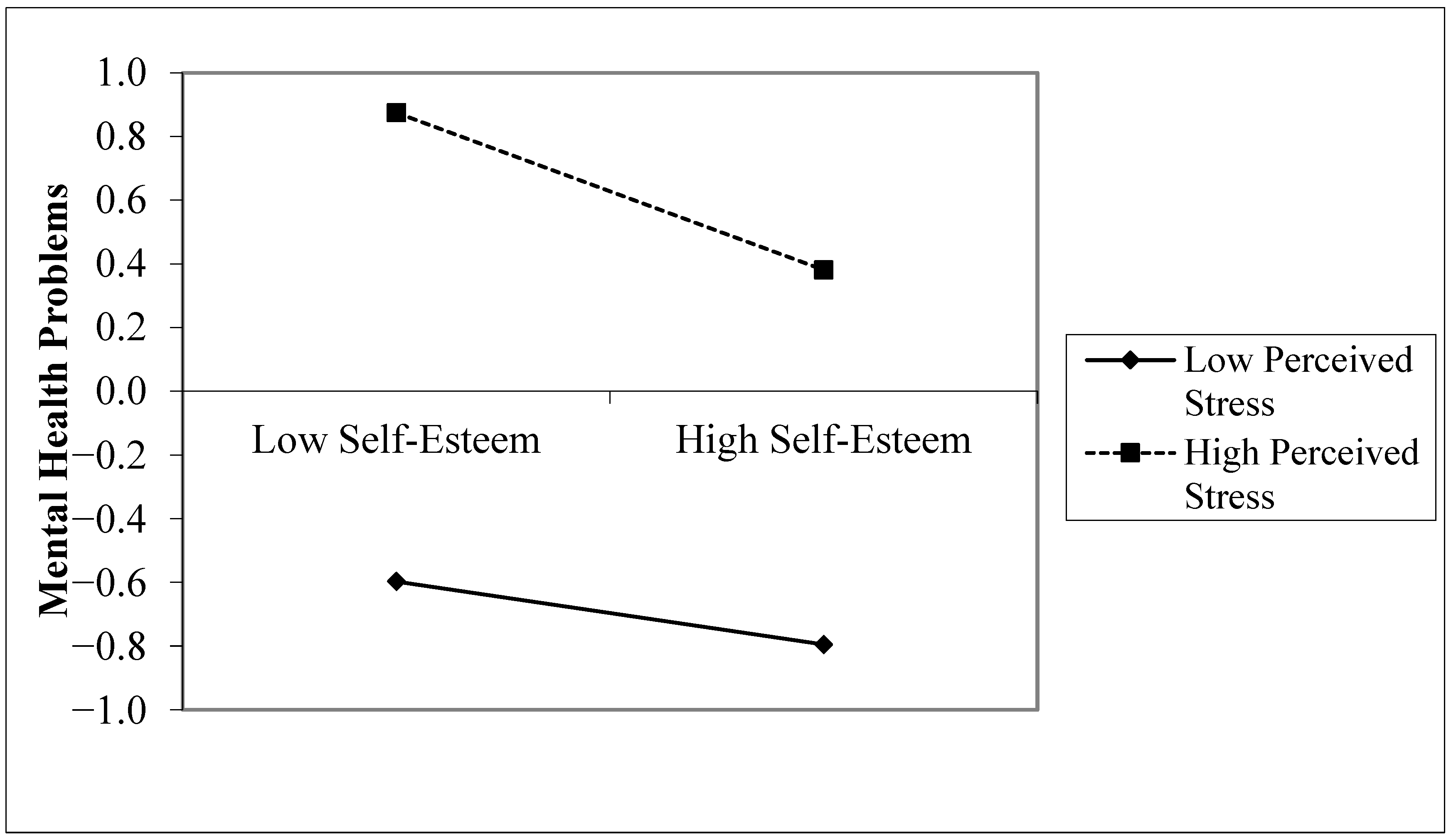

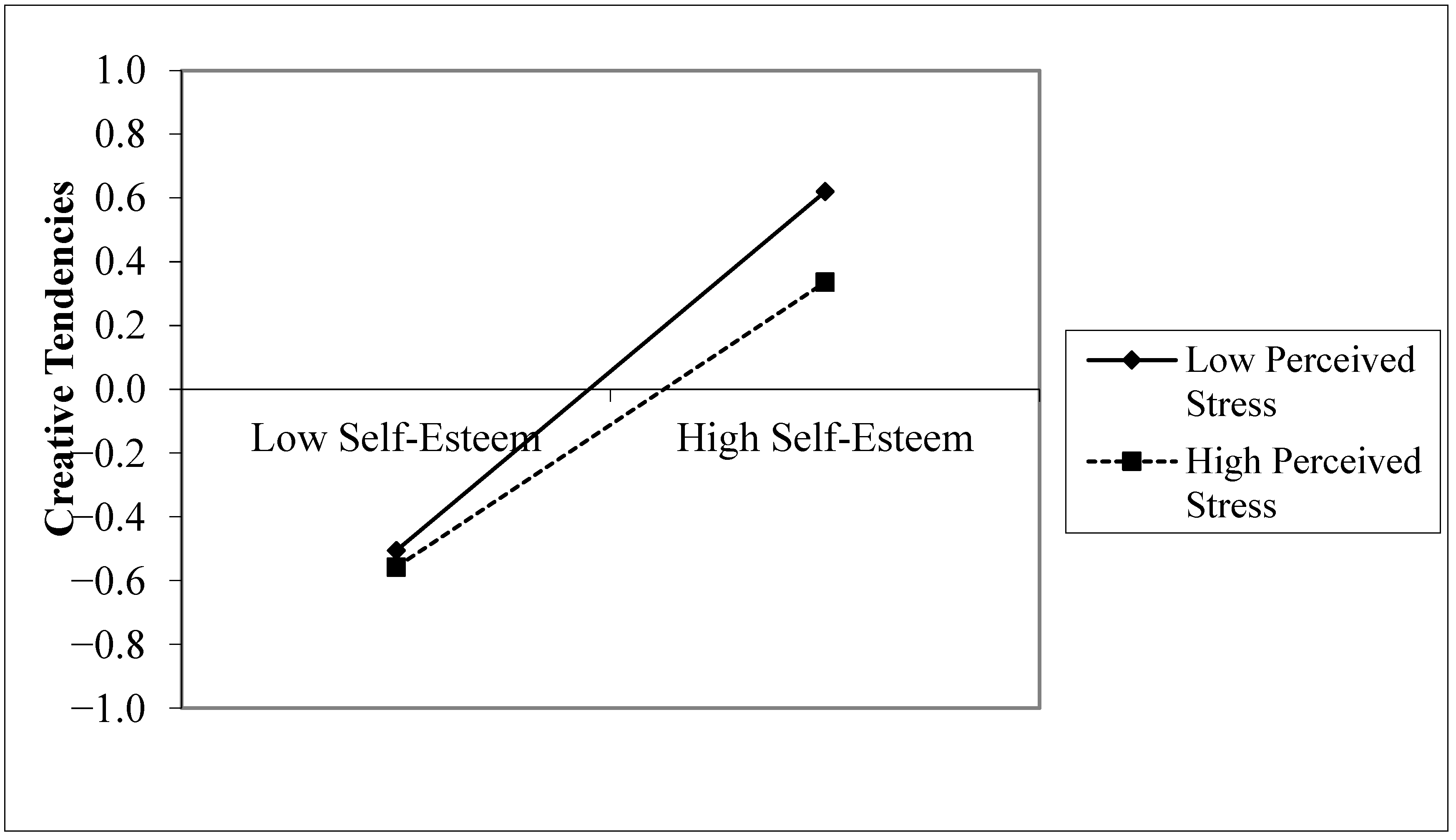

4.2.3. Moderating Effect Test

4.2.4. Test of Moderated Mediating Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. The Impact of Perceived Social Support on Mental Health Problems and Creative Tendencies

5.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem

5.3. The Moderating Role of Perceived Stress

5.4. Practical Implications and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, G. Prevalence of Mental Health Problems among Senior High School Students in Mainland of China from 2010 to 2020: A Meta-Analysis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 30, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R.A.; Dilley, A.E. Creative Aspirations or Pipe Dreams? Toward Understanding Creative Mortification in Children and Adolescents. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2016, 2016, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Vergara, M.; Barrios Galleguillos, N.; Jofré Cuello, L.; Alvarez-Marin, A.; Acuña-Opazo, C. Does Socioeconomic Status Influence Student Creativity? Think. Ski. Creat. 2018, 29, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steare, T.; Gutiérrez Muñoz, C.; Sullivan, A.; Lewis, G. The Association between Academic Pressure and Adolescent Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Qi, L.; Wan, G.; Li, B.; Hu, B. Child Population, Economic Development and Regional Inequality of Education Resources in China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 110, 104819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Operation Mechanism and Evaluation of “County High School Education Model” in the Context of Chinese College Entrance Examination System. Sci. Insights Educ. Front. 2020, 7, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Bai, B.; Bai, C. Body Image Dissatisfaction and Academic Buoyancy in Adolescents: The Mediating Roles of Social Anxiety and Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction. Psychol. Sch. 2023, 61, 832–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Social Relationship and Health. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefner, J.; Eisenberg, D. Social Support and Mental Health Among College Students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2009, 79, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.S.; Umberson, D.; Landis, K.R. Structures and Processes of Social Support. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1988, 14, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social Ties and Mental Health. J Urban Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.N. Context and Creativity: The Theory of Planned Behavior as an Alternative Mechanism. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2012, 40, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; You, S.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, X.; Song, C.; Yu, L.; Jiao, L. Associations between Social Networks and Creative Behavior during Adolescence: The Mediating Effect of Psychological Capital. Think. Ski. Creat. 2023, 49, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Xingli, Z.; Shi, J. The Relationships of Parental Responsiveness, Teaching Responsiveness, and Creativity: The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 748321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.; Costa, P.; Adonu, J. Social Support and Its Consequences: ‘Positive’ and ‘Deficiency’ Values and Their Implications for Support and Self-esteem. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 43, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zhang, X. Understanding the Relationship between Self-Esteem and Creativity: A Meta-Analysis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 19, 645. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Self-Esteem and Mental Health: The Sample of Chinese College Students. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 23, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development. Int. Encycl. Educ. 1994, 3, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayani, A.A. The Effect of Self-Esteem, Self-Efficacy and Family Social Support on Test Anxiety in Elementary Students: A Path Model. Int. J. Sch. Health 2016, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bum, C.-H.; Jeon, I.-K. Structural Relationships between Students’ Social Support and Self-Esteem, Depression, and Happiness. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2016, 44, 1761–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, Q.; Han, X.; Jiang, Y.; Ya, R.; Li, J. A Cross-Sectional Historical Study on the Changes in Self-Esteem among Chinese Adolescents from 1996 to 2019. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1280041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Y.; Lin, W.; Yang, J.; Huang, P.; Li, B.; Zhang, X. How Social Support Predicts Anxiety among University Students during COVID-19 Control Phase: Mediating Roles of Self-esteem and Resilience. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2022, 22, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Self-Construal and Creativity: The Moderator Effect of Self-Esteem. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 99, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakey, B.; Cassady, P.B. Cognitive processes in perceived social support. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, B.R.; Sarason, I.G.; Pierce, G.R. Traditional Views of Social Support and Their Impact on Assessment. In Social Support: An Interactional View; Wiley Series on Personality Processes; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 1990; pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Melrose, K.L.; Brown, G.D.A.; Wood, A.M. When Is Received Social Support Related to Perceived Support and Well-Being? When It Is Needed. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 77, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L. The Relation of Perceived and Received Social Support to Mental Health among First Responders: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 38, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Cleary, S.D. How Are Social Support Effects Mediated? A Test with Parental Support and Adolescent Substance Use. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Psychosocial Models of the Role of Social Support in the Etiology of Physical Disease. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 1988, 7, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, B.C.; Collins, N.L. Thriving through Relationships. Curr Opin Psychol 2015, 1, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harandi, T.F.; Taghinasab, M.M.; Nayeri, T.D. The Correlation of Social Support with Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. Electron Physician 2017, 9, 5212–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, M.; Zhou, S.-J.; Guo, Z.-C.; Zhang, L.-G.; Min, H.-J.; Li, X.-M.; Chen, J.-X. The Effect of Social Support on Mental Health in Chinese Adolescents During the Outbreak of COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, R.K. Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, R. Everyday Creativity: Process and Way of Life—Four Key Issues. In The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, F. Creativity Assessment Packet (CAP) Manual; DOK Publishers: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-Z.; Chang, T.-C.; Wu, C.-L. Effects of Gamified Classroom Management on the Divergent Thinking and Creative Tendency of Elementary Students. Think. Ski. Creat. 2020, 36, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Lu, Y.; Dai, D.Y.; Lin, C. Relationships between Migration to Urban Settings and Children’s Creative Inclinations. Creat. Res. J. 2013, 25, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, Q.; Gong, S.; Yi, L.; Cao, Y. Exploring the Effect of Perceived Teacher Support on Multiple Creativity Tasks: Based on the Expectancy–Value Model of Achievement Motivation. J. Creat. Behav. 2021, 55, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Conceiving the Self; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Yarcheski, A.; Mahon, N.E.; Yarcheski, T.J. Social Support and Well-Being in Early Adolescents: The Role of Mediating Variables. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2001, 10, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Tambor, E.S.; Terdal, S.K.; Downs, D.L. Self-Esteem as an Interpersonal Monitor: The Sociometer Hypothesis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. Causes and Consequences of Low Self-Esteem in Children and Adolescents. In Self-Esteem: The Puzzle of Low Self-Regard; Plenum Series in Social/Clinical Psychology; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Yuan, R.; Chen, J.-K. Social Support and Depression among Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Roles of Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 88, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, J.M.; Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J. Does Adolescent Self-Esteem Predict Later Life Outcomes? A Test of the Causal Role of Self-Esteem. Dev. Psychopathol. 2008, 20, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.; Hosman, C.; Schaalma, H.; Vries, N. Self-Esteem in a Broad-Spectrum Approach for Mental Health Promotion. Health Educ. Res. 2004, 19, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; He, J.; Fan, X. Relationships between Openness to Experience, Cognitive Flexibility, Self-Esteem, and Creativity among Bilingual College Students in the U.S. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2022, 25, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.; Ng, B. Self-Esteem as the Mediating Factor between Parenting Styles and Creativity. Int. J. Cogn. Behav. 2019, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alfiani, I.; Dwijanto, D.; Cahyono, A.N. Mathematical Creative Thinking Ability Viewed by Self-Esteem in Problem-Based Learning with Open Ended Approach. Unnes J. Math. Educ. Res. 2019, 8, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Theory-Based Stress Measurement. Psychol. Inq. 1990, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Huang, J.; An, Y.; Xu, W. The Relationship between Stress and Negative Emotion: The Mediating Role of Rumination. Clin. Res. Trials 2018, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; Psychology Foundation of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 1995; Volume 56. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965; pp. 16–36. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Lipman, R.S.; Rickels, K.; Uhlenhuth, E.H.; Covi, L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A Self-Report Symptom Inventory. Behav. Sci. 1974, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, B. A Study on the Structure and Development of Adolescents’ Creative Tendencies. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2005, 21, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanhai, A.; Singh, B. Some Environmental and Attitudinal Characteristics as Predictors of Mathematical Creativity. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 48, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zanden, P.; Meijer, P.; Beghetto, R. A Review Study about Creativity in Adolescence: Where Is the Social Context? Think. Ski. Creat. 2020, 38, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fu, H.; Zhang, Y. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Perceived Social Support and Student Academic Achievement: The Mediating Role of Student Engagement. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 31, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippon, D.; Shepherd, J.; Wakefield, S.; Lee, A.; Pollet, T.V. The Role of Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem in Mediating Positive Associations between Functional Social Support and Psychological Wellbeing in People with a Mental Health Diagnosis. J. Ment. Health 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsén, F.; Antonson, C.; Palmér, K.; Berg, R.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Associations between Perceived Stress and Health Outcomes in Adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K.; Khazanchi, S.; Nazarian, D. The Relationship between Stressors and Creativity: A Meta-Analysis Examining Competing Theoretical Models. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gothe, N.P.; Erlenbach, E.; Engels, H.-J. Exercise and Self-Esteem Model: Validity in a Sample of Healthy Female Adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 8876–8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulier, V.; Guinet, H.; Kovacevic, Z.; Bel-Abbass, Z.; Benamara, Y.; Zile, N.; Ourrad, A.; Arcella-Giraux, P.; Meunier, E.; Thomas, F.; et al. Effects of a Life-Skills-Based Prevention Program on Self-Esteem and Risk Behaviors in Adolescents: A Pilot Study. BMC Psychol. 2019, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafizh, Z.A.; Partino; Madjid, A. Enhancing Student Well-Being through AI Chat GPT in the Smart Education University Learning Environment: A Preliminary Review of Research Literature. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 440, 05005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Q.; Zhang, Z.-R. Potential Use of Large Language Models for Mitigating Students’ Problematic Social Media Use: ChatGPT as an Example. World J. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, S.; Irwin Hamilton, K.; Yuan, Y.; Wallis Hague, G. Assessment of Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) as a Stress-Reducing Technique for First-Year Veterinary Students. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2020, 47, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkoby, A.; Pliskin, R.; Halperin, E.; Levit-Binnun, N. An Eight-Week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Workshop Increases Regulatory Choice Flexibility. Emotion 2019, 19, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghannam, J.; Afana, A.; Ho, E.Y.; Al-Khal, A.; Bylund, C.L. The Impact of a Stress Management Intervention on Medical Residents’ Stress and Burnout. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2020, 27, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PSS | 5.011 ± 0.964 | 1 | ||||

| 2. MHP | 1.783 ± 0.618 | −0.461 ** | 1 | |||

| 3. CT | 3.406 ± 0.472 | 0.318 ** | −0.322 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. Self-Esteem | 2.961 ± 0.495 | 0.414 ** | −0.489 ** | 0.545 ** | 1 | |

| 5. PS | 1.775 ± 0.564 | −0.429 ** | 0.763 ** | −0.308 ** | −0.464 ** | 1 |

| Predictor | Independent Variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Esteem | MHP | Creative Tendencies | |

| Gender | 0.066 ** | 0.007 | 0.052 * |

| Age | −0.024 | 0.009 | 0.011 |

| Grade | 0.128 ** | 0.011 | 0.054 |

| Boarding Student | −0.043 | 0.050 ** | −0.016 |

| PSS | 0.421 *** | −0.128 *** | 0.114 *** |

| Self-Esteem | −0.136 *** | 0.472 *** | |

| Self-Esteem× PS | −0.075 *** | −0.057 * | |

| PS | 0.622 *** | −0.049 | |

| R2 | 0.192 | 0.627 | 0.320 |

| Independent Variable | Value of Moderator | Indirect Effect | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHP | Low PS (M − SD) | −0.026 | −0.045 | −0.006 |

| High PS (M + SD) | −0.089 | −0.117 | −0.062 | |

| Contrast | −0.064 | −0.094 | −0.033 | |

| Creative Tendencies | Low PS (M − SD) | 0.223 | 0.181 | 0.265 |

| High PS (M + SD) | 0.175 | 0.138 | 0.212 | |

| Contrast | −0.048 | −0.091 | −0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, D.; Dong, Y.; Kong, A.; Li, X. How Does Perceived Social Support Impact Mental Health and Creative Tendencies Among Chinese Senior High School Students? Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111002

Gao D, Dong Y, Kong A, Li X. How Does Perceived Social Support Impact Mental Health and Creative Tendencies Among Chinese Senior High School Students? Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(11):1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111002

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Dongdong, Yixuan Dong, Anran Kong, and Xiaoyu Li. 2024. "How Does Perceived Social Support Impact Mental Health and Creative Tendencies Among Chinese Senior High School Students?" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 11: 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111002

APA StyleGao, D., Dong, Y., Kong, A., & Li, X. (2024). How Does Perceived Social Support Impact Mental Health and Creative Tendencies Among Chinese Senior High School Students? Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111002