The Impact of Short-Form Video and Optimistic Bias on Engagement in Oral Health Prevention: Integrating a KAP Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

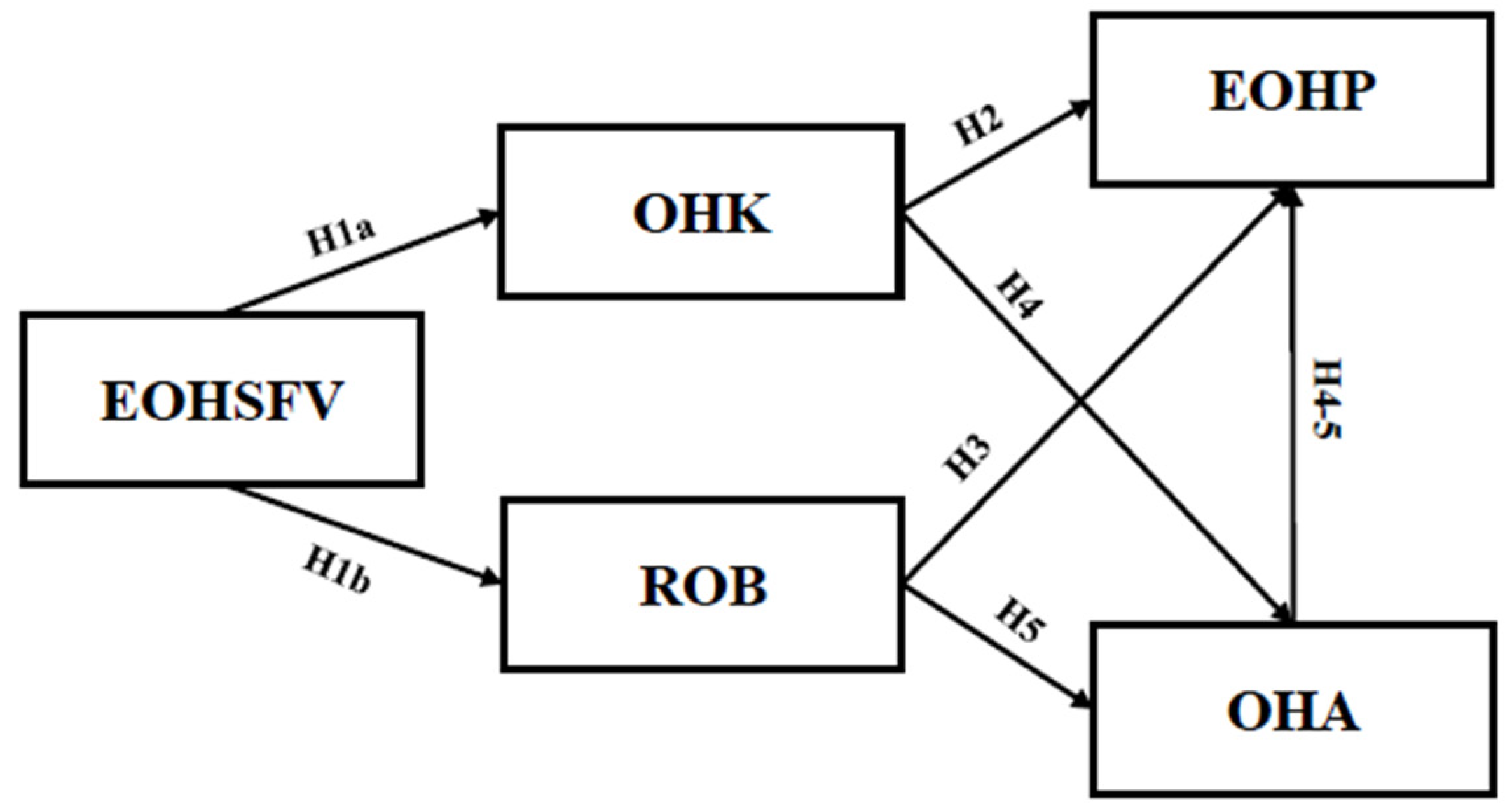

2.1. Extended KAP Theory Model

2.2. EOHSFV on KAP Constructs and ROB

2.3. The Mediating Roles of OHK and ROB

3. Methods

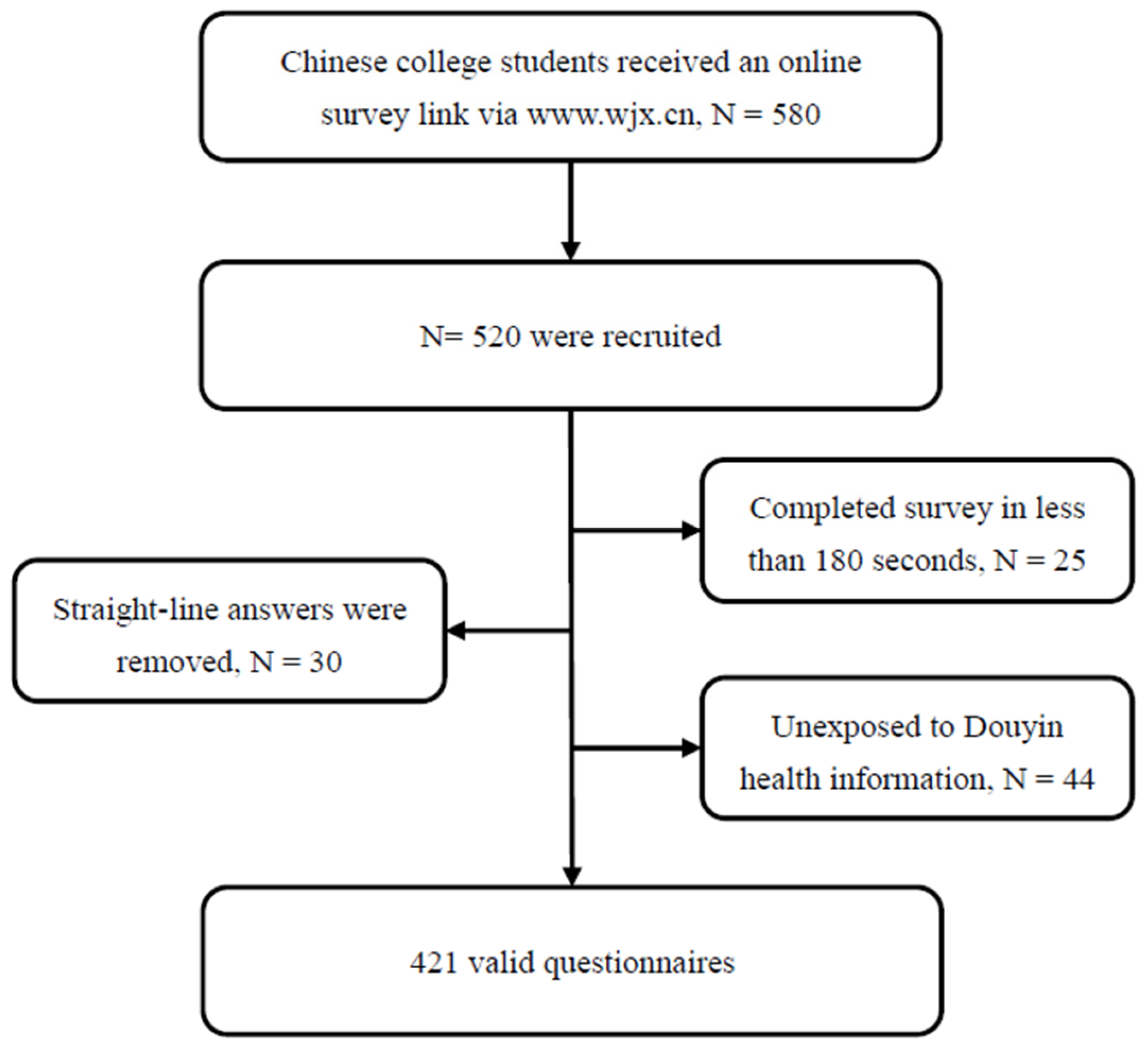

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Data

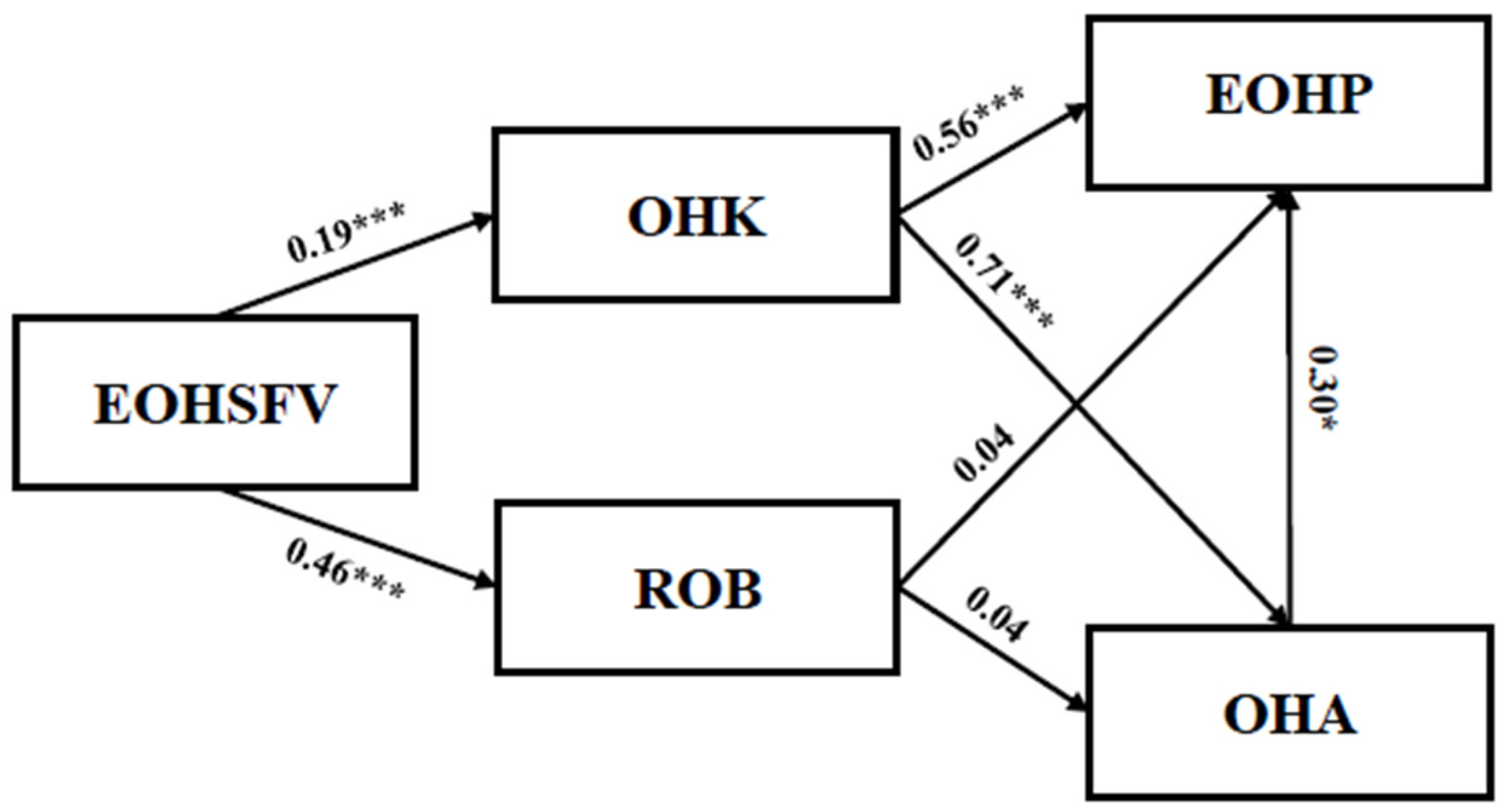

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Source | Items | Loading | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to oral health short-form videos (EOHSFV) | Liu et al. (2020) [77] | Dental health practical tips short videos. | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.77 |

| Dental drama short videos. | 0.90 | |||||

| Oral health popular science short videos (e.g., causes of cavities and wisdom teeth). | 0.90 | |||||

| Dental imaging short videos (e.g., X-rays). | 0.87 | |||||

| Oral care product introduction and marketing short videos. | 0.82 | |||||

| Reversed optimistic bias (ROB) | van der Meer et al. (2023) [78] | I may be more susceptible to oral diseases than others. | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.75 |

| Oral diseases may disrupt my life and work rhythm compared to others. | 0.91 | |||||

| Oral diseases may lead to more severe health consequences for me compared to others. | 0.90 | |||||

| Oral diseases may have more severe economic consequences for me than others. | 0.84 | |||||

| Oral health knowledge (OHK) | Tadin et al. (2022) [79] | In order to prevent tooth decay, it is necessary to brush teeth frequently (with emphasis on the crown). | 0.66 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 0.50 |

| You should brush your teeth every morning and before bed every night. | 0.65 | |||||

| Plaque can lead to gum disease and cavities. | 0.77 | |||||

| Gum bleeding is a sign of gum disease. | 0.76 | |||||

| Diabetes increases the risk of gum disease. | 0.68 | |||||

| It is especially important to gargle at least once a day. | 0.74 | |||||

| Smoking/vaping is associated with the occurrence of periodontitis. | 0.67 | |||||

| It is necessary to visit the dentist regularly to check the condition of the mouth and to have a professional cleaning. | 0.75 | |||||

| Maintain oral health by eating a strictly balanced diet and limiting sweets (including sugary drinks). | 0.70 | |||||

| Oral health attitude (OHA) | Francis et al. (2004) [80]; Ajzen (2006) [102]; Ho et al. (2015) [103] | I believe that oral health practices are pleasant. | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.96 | 0.66 |

| I believe that oral health practices are beneficial. | 0.87 | |||||

| I believe that oral health practices are good. | 0.81 | |||||

| I believe that oral health practices are important. | 0.73 | |||||

| Engagement in oral health prevention (EOHP) | Brennan et al. (2010) [81]; Zheng et al. (2021) [37] | I avoid sweets, fizzy drinks, tobacco, and alcohol to prevent oral diseases. | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.73 |

| I have regular oral care (e.g., brushing my teeth, removing tartar, and removing plaque). | 0.90 | |||||

| I visit the dentist regularly to prevent oral diseases. | 0.88 |

References

- GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators; Bernabe, E.; Marcenes, W.; Hernandez, C.; Bailey, J.; Abreu, L.; Alipour, V.; Amini, S.; Arabloo, J.; Arefi, Z. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2017 study. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R.; Haque, M. Oral health messiers: Diabetes mellitus relevance. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 3001–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Marco del Castillo, A.; Jepsen, S.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; D’Aiuto, F.; Bouchard, P.; Chapple, I.; Dietrich, T.; Gotsman, I.; Graziani, F. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: Consensus report. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Morales, A.; González-López, B.S.; Scougall-Vilchis, R.J.; Bermeo-Escalona, J.R.; Velázquez-Enríquez, U.; Islas-Zarazúa, R.; Márquez-Rodríguez, S.; Sosa-Velasco, T.A.; Medina-Solís, C.E.; Maupomé, G. Lip and oral cavity cancer incidence and mortality rates associated with smoking and chewing tobacco use and the human development index in 172 countries worldwide: An ecological study 2019–2020. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Oral Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Acuña-González, G.R.; Casanova-Sarmiento, J.A.; Islas-Granillo, H.; Márquez-Rodríguez, S.; Benítez-Valladares, D.; Mendoza-Rodríguez, M.; de la Rosa-Santillana, R.; Navarrete-Hernández, J.d.J.; Medina-Solís, C.E.; Maupomé, G. Socioeconomic inequalities and toothbrushing frequency among schoolchildren aged 6 to 12 years in a multi-site study of mexican cities: A cross-sectional study. Children 2022, 9, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, T.; Tada, M.; Shiratori, T.; Imai, M.; Onose, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Satou, R.; Ishizuka, Y.; Sugihara, N. Factors associated with undergoing regular dental check-ups in healthy elderly individuals. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2018, 59, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, P.E.; Baez, R.J.; Ogawa, H. Global application of oral disease prevention and health promotion as measured 10 years after the 2007 World Health Assembly statement on oral health. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2020, 48, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Ting, C.C.; Wu, J.H.; Lee, K.T.; Chen, H.S.; Chang, Y.Y. Dental visiting behaviours among primary schoolchildren: Application of the health belief model. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2018, 16, e88–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrabani, S. Factors affecting oral examinations and dental treatments among older adults in Israel. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2019, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DCHB. More Than 1.1 Million Free Cavity and Groove Sealing Teeth, the Incidence of Dental Caries in Dongguan Children Decreased by 50%. 2021. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/71ngbJfzcC-o7BoAbEYAdA (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- CY. Combined with Professional Expertise, University Student Volunteers Preach Oral Health but “18 Martial Arts” All. 2024. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/fg0tHgxelnk2UkoR8_0ceQ (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Zhang, J. Analyzes how short-form video apps affects popular culture and people’s entertainment. In Rethinking Communication and Media Studies in the Disruptive Era; European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences; European Publisher: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Omar, B.; Musetti, A. The addiction behavior of short-form video app tiktok: The information quality and system quality perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 932805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L. Investigating the existing state of health information dissemination on the tiktok short video platform and potential solutions. Probe Media Commun. Stud. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C. Research on the flow experience and social influences of users of short online videos. A case study douyin. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Humor and camera view on mobile short-form video apps influence user experience and technology-adoption intent, an example of TikTok (DouYin). Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 110, 106373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. TikTok’s influence on Education. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2023, 8, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriç, P.; Kılınç, D.D. Evaluation of quality and reliability of videos about orthodontics on tiktok (douyin). APOS Trends Orthod 2022, 12, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfmann, S. The Quality of Information on Oral Hygiene Instructions for Orthodontic Patients in Tiktok Videos. Master’s Thesis, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Adnan, H.M.; Alivi, M.A.; Sarmiti, N.Z. Unveiling the influence of tiktok dependency on university students’ post-covid-19 health protective behavior. Stud. Media Commun. 2024, 12, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareban, I.; Rahmani, A.; Allahqoli, L.; Ghanei Gheshlagh, R.; Hashemian, M.; Khayyati, F.; Chan, W.-c.; Volken, T.; Nemat, B. Effect of education based on trans-theoretical model in social media on students with gingivitis; a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerman, J.F.M.; Hamilton, K.; Sharif, M.O.; Lindmark, U.; Pakpour, A.H. A theory-based intervention delivered by an online social media platform to promote oral health among Iranian adolescents: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Health 2020, 35, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Espanha, R. Association of sina-microblog use with knowledge, attitude and practices towards COVID-19 control in china. Open Access J. Public Health 2021, 7, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, Y.; Tang, X.; Gan, L.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, T.; Peng, B. Research on knowledge, attitudes, and practices of influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in chongqing, china—based on structural equation model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 853041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Abbas, J.; Draghici, A.; Negulescu, O.H.; Ain, N.U. Social media application as a new paradigm for business communication: The role of COVID-19 knowledge, social distancing, and preventive attitudes. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 903082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahani, B.; Asgari, I.; Golkar, S.; Ghorani, A.; Hasan Zadeh Tehrani, N.; Arezoo Moghadam, F. Effectiveness of an integrated model of oral health-promoting schools in improving children’s knowledge and the KAP of their parents, Iran. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboalshamat, K.; Alharbi, J.; Alharthi, S.; Alnifaee, A.; Alhusayni, A.; Alhazmi, R. The effects of social media (Snapchat) interventions on the knowledge of oral health during pregnancy among pregnant women in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WLLH. Oral Health of College Students. 2024. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Csv64BdwgvbkBgiwHbuHCg (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Hochbaum, G.M. Public Participation in Medical Screening Programs: A Socio-Psychological Study; US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Bureau of State Services, Division of Special Health Services, Tuberculosis Program: Washington, DC, USA, 1958; p. 572.

- Launiala, A. How much can a KAP survey tell us about people’s knowledge, attitudes and practices? Some observations from medical anthropology research on malaria in pregnancy in Malawi. Anthropol. Matters 2009, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.T.; Rav-Marathe, K.; Marathe, S. A systematic review of kap-o framework for diabetes. Med. Res. Arch. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, N.; Shi, S.; Duan, Y.; Ma, G.; Li, X.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Luo, A.; Zhong, Z. Social media use, eHealth literacy, knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese college students in the phase of regular epidemic prevention and control: A cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 754904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kang, B.-A.; You, M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) toward COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in South Korea. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhao, L.; Ju, N.; Hua, T.; Zhang, S.; Liao, S. Relationship between oral health-related knowledge, attitudes, practice, self-rated oral health and oral health-related quality of life among Chinese college students: A structural equation modeling approach. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yezli, S.; Yassin, Y.; Mushi, A.; Maashi, F.; Aljabri, N.; Mohamed, G.; Bieh, K.; Awam, A.; Alotaibi, B. Knowledge, attitude and practice (kap) survey regarding antibiotic use among pilgrims attending the 2015 Hajj mass gathering. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 28, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Lai, X.; Tan, L.; Zhou, Q.; Duan, L.; Lin, R.; Wang, X.; Zheng, F. The impacts of knowledge and attitude on behavior of antibiotic use for the common cold among the public and identifying the critical behavioral stage: Based on an expanding KAP model. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Cunha, D.T.; de Rosso, V.V.; Pereira, M.B.; Stedefeldt, E. The differences between observed and self-reported food safety practices: A study with food handlers using structural equation modeling. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bao, S. The impact of exposure to HPV related information and injunctive norms on young women’s intentions to receive the HPV vaccine in China: A structural equation model based on KAP theory. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, R.; Lo, V.-H.; Lu, H.-Y. Reconsidering the relationship between the third-person perception and optimistic bias. Commun. Res. 2007, 34, 665–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkaki, I.; Maciejewski, D.F.; Weijman, E.L.; Feltes, J.; Cima, M. Human responses to COVID-19: The role of optimism bias, perceived severity, and anxiety. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 176, 110781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pettersson, E.; Schandl, A.; Markar, S.; Johar, A.; Lagergren, P. Higher dispositional optimism predicts better health-related quality of life after esophageal cancer surgery: A nationwide population-based longitudinal study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 7196–7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Niederdeppe, J. Exploring optimistic bias and the integrative model of behavioral prediction in the context of a campus influenza outbreak. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strombotne, K.; Sindelar, J.; Buckell, J. Who, me? Optimism bias about US teenagers’ ability to quit vaping. Addiction 2021, 116, 3180–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, D.T.; Braga, A.R.C.; de Camargo Passos, E.; Stedefeldt, E.; de Rosso, V.V. The existence of optimistic bias about foodborne disease by food handlers and its association with training participation and food safety performance. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A.; Ismangil, M.; He, W.; Cao, S. If I’m not Streaming, I’m not Earning: Audience relations and platform time on douyin. Online Media Glob. Commun. 2022, 1, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Liechty, T.; Santos, C.A.; Park, J. ‘I want to record and share my wonderful journey’: Chinese Millennials’ production and sharing of short-form travel videos on TikTok or Douyin. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 3412–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Song, S.; Zhao, Y.C.; Zhu, Q.; Sha, L. TikTok as a health information source: Assessment of the quality of information in diabetes-related videos. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e30409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Nguyen, T.P.L.; Sasaki, N. Use of the knowledge, attitude, and practice (kap) model to examine sustainable agriculture in Thailand. Reg. Sustain. 2022, 3, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Asawasirisap, P.; Kearney, J. Knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) towards diet and health among international students in Dublin: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.u.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Zeb, F.; Jiang, P.; Wu, X.; Tian, Y. Association of smoking-related knowledge, attitude, and practices (kap) with nutritional status and diet quality: A cross-sectional study in china. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 5897478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, H.R.; Sijali, T.R.; Bogati, R.; Clarke, A.; Adhikary, P.; Karkee, R. How does public knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors correlate in relation to COVID-19? A community-based cross-sectional study in Nepal. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 589372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickens, J. Attitudes and perceptions. Organ. Behav. Health Care 2005, 4, 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K.A.; Roloff, M.E.; Friesema, E.M.; Brown, T.; Jovanovic, B.D.; Hauber, S.; Baker, D.W. Patient knowledge and recall of health information following exposure to “facts and myths” message format variations. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 92, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melki, J.; Tamim, H.; Hadid, D.; Farhat, S.; Makki, M.; Ghandour, L.; Hitti, E. Media exposure and health behavior during pandemics: The mediating effect of perceived knowledge and fear on compliance with COVID-19 prevention measures. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.; Bottorff, J.L.; Ratner, P.A.; Gotay, C.; Johnson, K.C.; Memetovic, J.; Richardson, C.G. Effect of web-based messages on girls’ knowledge and risk perceptions related to cigarette smoke and breast cancer: 6-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2014, 3, e3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.C.; Kyle, D.; Swan, J.; Thomas, C.; Vrungos, S. Increasing condom use by undermining perceived invulnerability to HIV. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2002, 14, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W. They liked and shared: Effects of social media virality metrics on perceptions of message influence and behavioral intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M. The message influences me more than others: How and why social media metrics affect first person perception and behavioral intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 91, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, S.; Romero, C.; Carcamo, C.; Tinoco, Y.; Valderrama, M.; La Rosa, S.; Mallma, P.; Neyra, J.; Soto, G.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E. A community-based survey on influenza and vaccination knowledge, perceptions and practices in Peru. Vaccine 2020, 38, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, R.; Chen, B.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, H.; Wang, H. Knowledge, perceived beliefs, and preventive behaviors related to COVID-19 among Chinese older adults: Cross-sectional web-based survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e23729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milam, J.E.; Sussman, S.; Ritt-Olson, A.; Dent, C.W. Perceived invulnerability and cigarette smoking among adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2000, 25, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Lo, V.-H.; Lu, H.-Y.; Hou, H.-Y. Examining multiple behavioral effects of third-person perception: Evidence from the news about Fukushima nuclear crisis in Taiwan. Chin. J. Commun. 2015, 8, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, A.L.; Wagle, M.; Dogaru, B.C.; Manolescu, B. Modeling the theory of planned behavior for intention to improve oral health behaviors: The impact of attitudes, knowledge, and current behavior. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 53, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.M. Factors associated with knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to oral care among the elderly in Hong Kong community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Shah, S.; Ahmad, A.; Fatokun, O. Knowledge and attitude of healthcare workers about middle east respiratory syndrome in multispecialty hospitals of Qassim, Saudi Arabia. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Ackerman, J.M.; Bargh, J.A. Superman to the rescue: Simulating physical invulnerability attenuates exclusion-related interpersonal biases. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Linder, A.D.; Harper, A.; Jung, J.; Woodson-Smith, A. Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviors attitude and intention and their impact on physical activity among college students enrolled in lifetime fitness courses. Coll. Stud. J. 2017, 51, 550–560. [Google Scholar]

- Fernbach, P.M.; Light, N.; Scott, S.E.; Inbar, Y.; Rozin, P. Extreme opponents of genetically modified foods know the least but think they know the most. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellinda-Patra, M.; Dewanti-Hariyadi, R.; Nurtama, B. Modeling of food safety knowledge, attitude, and behavior characteristics. Food Res. 2020, 4, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Wu, F.; Li, Q.; Lin, Q.; Cao, H.; Zhou, X.; Gu, Z.; Chen, Q. Heightened willingness toward pneumococcal vaccination in the elderly population in Shenzhen, China: A cross-sectional study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines 2021, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cui, G.; Yin, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, L. Health-promoting behaviors mediate the relationship between eHealth literacy and health-related quality of life among Chinese older adults: A cross-sectional study. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 2235–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Swarlik, V.J.; Grethe, G.A.; Schillack, H.; Margraf, J. Experimental longitudinal evidence for causal role of social media use and physical activity in COVID-19 burden and mental health. J. Public Health 2023, 31, 1885–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelcey, B.; Bai, F.; Xie, Y. Statistical power in partially nested designs probing multilevel mediation. Psychother. Res. 2020, 30, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H. Media exposure to COVID-19 information, risk perception, social and geographical proximity, and self-rated anxiety in China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, T.G.; Brosius, A.; Hameleers, M. The role of media use and misinformation perceptions in optimistic bias and third-person perceptions in times of high media dependency: Evidence from four countries in the first stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mass Commun. Soc. 2022, 26, 438–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadin, A.; Poljak Guberina, R.; Domazet, J.; Gavic, L. Oral hygiene practices and oral health knowledge among students in split, croatia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, J.; Eccles, M.P.; Johnston, M.; Walker, A.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Foy, R.; Kaner, E.F.; Smith, L.; Bonetti, D. Constructing Questionnaires Based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Manual for Health Services Researchers; Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, D.; Spencer, J.; Roberts-Thomson, K. Dental knowledge and oral health among middle-aged adults. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2010, 34, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Chang, L.L.; Backman, K.F. Detecting common method bias in predicting creative tourists behavioural intention with an illustration of theory of planned behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xie, J.; Li, K.; Ji, S. Exploring how media influence preventive behavior and excessive preventive intention during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Hayat, N.; Mohiuddin, M.; Salameh, A.A.; Zainol, N.R. Modelling the energy conservation behaviour among Chinese households under the premises of value-belief-norm theory. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 954595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, W.; Tripopsakul, S. Explaining social Media adoption for a business purpose: An application of the UTAUT model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.; Milman, A. Exploring experiential consumption dimensions in the theme park context. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 853–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V. When to use hierarchical linear modeling. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2014, 10, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.R.; Windschitl, P.D.; Suls, J. Egocentrism, event frequency, and comparative optimism: When what happens frequently is “more likely to happen to me”. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Orts, C.; Rey, L.; Chamizo-Nieto, M.T.; Worthington Jr, E.L. A serial mediation model of the relationship between cybervictimization and cyberaggression: The role of stress and unforgiveness motivations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjit, Y.S.; Shin, H.; First, J.M.; Houston, J.B. COVID-19 protective model: The role of threat perceptions and informational cues in influencing behavior. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, F.; Rossi, L. Sustainable choices: The relationship between adherence to the dietary guidelines and food waste behaviors in italian families. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1026829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, M.; Ahmad, T.; Qi, X.; Murad, M.A.; Baig, M.; Sagga, A.K.; Tariq, S.; Baig, F.; Naz, R.; Hui, J. Social media use, psychological distress and knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding the COVID-19 among a sample of the population of Pakistan. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 754121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, J.; Denmon, J. Interactions with COVID-19 content on social media: Outcomes of social media use on student KAPs. J. Stud. Res. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.M.; Rouf, A.S.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Exploring young adult perspectives on the use of gamification and social media in a smartphone platform for improving vegetable intake. Appetite 2018, 120, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitroyannis, R.; Cho, S.; Thodupunoori, S.; Fenton, D.; Nordgren, R.; Roxbury, C.R.; Shogan, A. “Does my kid have an ear infection?” an analysis of pediatric acute otitis media videos on tiktok. Laryngoscope 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, S.; Eagle, L. Empowering or misleading? Online health information provision challenges. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2016, 34, 1000–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwig, P.; Dalrymple, K.E.; Brossard, D.; Scheufele, D.A.; Corley, E.A. Perceived familiarity or factual knowledge? Comparing operationalizations of scientific understanding. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Ho, S.S. Does media exposure relate to the illusion of knowing in the public understanding of climate change? Public Underst. Sci. 2020, 29, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, I. Digital Health Promotion: A Critical Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Bol, N.; King, A.J. Customisation versus personalisation of digital health information: Effects of mode tailoring on information processing outcomes. Eur. J. Health Commun. 2020, 1, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-L.; Yin, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, X. The differential effects of trusting beliefs on social media users’ willingness to adopt and share health knowledge. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. Amherst, MA. 2006. Available online: http://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Ho, S.S.; Liao, Y.; Rosenthal, S. Applying the theory of planned behavior and media dependency theory: Predictors of public pro-environmental behavioral intentions in singapore. Environ. Commun. 2015, 9, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOHSFV | 0.88 | ||||

| ROB | 0.48 ** | 0.86 | |||

| OHK | 0.32 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.71 | ||

| OHA | 0.31 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.81 | |

| EOHP | 0.57 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.85 |

| Variables | Item | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 208 | 49.4% |

| Male | 213 | 50.6% | |

| Education level | Undergraduate | 328 | 77.9% |

| Postgraduate | 93 | 22.1% | |

| Age | 18–21 years old | 136 | 32.3% |

| 22–25 years old | 167 | 39.7% | |

| 26–30 years old | 118 | 28.0% | |

| Monthly household income (RMB) | 1000–3999 | 68 | 16.2% |

| 4000–8999 | 134 | 31.9% | |

| 9000–13,999 | 116 | 27.6% | |

| >14,000 RMB | 103 | 24.5% | |

| Total | 421 | 100% |

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | EOHSFV has a significant and positive effect on Chinese college students’ (a) OHK and (b) ROB. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 2 | OHK mediates the relationship between EOHSFV and Chinese college students’ EOHP. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 3 | ROB mediates the relationship between EOHSFV and Chinese college students’ EOHP. | Rejected |

| Hypothesis 4 | OHK and OHA play a serial mediating role in the relationship between EOHSFV and Chinese college students’ EOHP. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 5 | ROB and OHA play a serial mediating role in the relationship between EOHSFV and Chinese college students’ EOHP. | Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chung, D.; Wang, J.; Meng, Y. The Impact of Short-Form Video and Optimistic Bias on Engagement in Oral Health Prevention: Integrating a KAP Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100968

Chung D, Wang J, Meng Y. The Impact of Short-Form Video and Optimistic Bias on Engagement in Oral Health Prevention: Integrating a KAP Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):968. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100968

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Donghwa, Jiaqi Wang, and Yanfang Meng. 2024. "The Impact of Short-Form Video and Optimistic Bias on Engagement in Oral Health Prevention: Integrating a KAP Model" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100968

APA StyleChung, D., Wang, J., & Meng, Y. (2024). The Impact of Short-Form Video and Optimistic Bias on Engagement in Oral Health Prevention: Integrating a KAP Model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100968