Dating Violence and the Quality of Relationships through Adolescence: A Longitudinal Latent Class Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Risk Factors for Involvement in Violence: The Quality of the Relationship

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

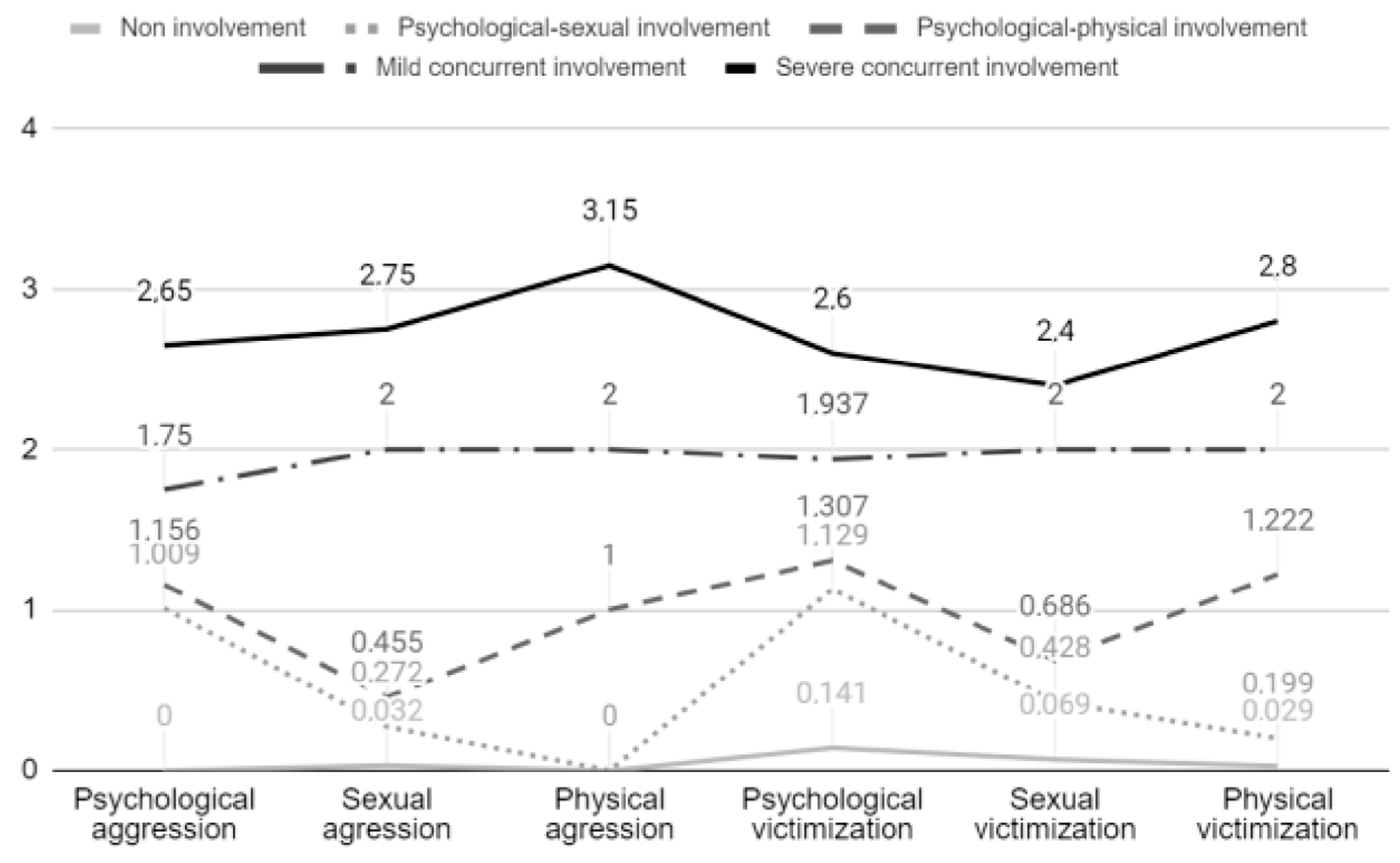

3.1. Latent Classes of Involvement in Violence

3.2. Relationship Quality and Involvement in Violence

4. Discussion, Conclusions, and New Research Challenges

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Viejo, C.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Sánchez, V. Adolescent love and well-being: The role of dating relationships for psychological adjustment. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 18, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halberstadt, A.G.; Denham, S.A.; Dunsmore, J.C. Affective social competence. Soc. Dev. 2001, 10, 79–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, W.A.; Steinberg, L. Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In Child and Adolescent Development: An Advanced Course; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 551–590. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, A.; Fortin, L.; Paradis, A.; Hébert, M. Relationship quality among dating adolescents: Development and validation of the Relationship Quality Inventory for Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1026507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, R.; Sánchez, V. Juvenile dating and violence. In Bullying in Different Contexts; Monks, C.P., Coyne, I., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menesini, E.; Nocentini, A.; Ortega-Rivera, F.J.; Sanchez, V.; Ortega, R. Reciprocal involvement in adolescent dating aggression: An Italian–Spanish study. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 8, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccì, G.; Confalonieri, E.; Olivari, M.G.; Borroni, E.; Davila, J. Adolescent romantic relationships as a tug of war: The interplay of power imbalance and relationship duration in adolescent dating aggression. Aggress. Behav. 2020, 46, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viejo, C.; Gómez-López, M.; Ortega-Ruiz, R. Adolescents’ Psychological Well-Being: A Multidimensional Measure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, P.V.; Guevara-Martínez, C.; Rojas-Solís, J.L.; Peña-Cárdenas, F.; González Cruz, V.G. Apego y ciber-violencia en la pareja de adolescentes. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. Rev. INFAD Psicol. 2017, 2, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.H.; White, J.W.; Holland, L.J. A Longitudinal Perspective on Dating Violence Among Adolescent and College-Age Women. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Garay, F.; López-González, M.A.; Carrasco, M.Á.; Amor, P. Prevalencia de la Violencia en el Noviazgo: Una Revisión Sistemática. Papeles Del Psicol.-Psychol. Pap. 2017, 37, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.G.; Okeem, C.; Piquero, A.R.; Sellers, C.S.; Theobald, D.; Farrington, D.P. Dating and intimate partner violence among young persons ages 15–30: Evidence from a systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 33, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Storey, A.; Fromme, K. Mediating Factors Explaining the Association Between Sexual Minority Status and Dating Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 36, 132–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thulin, E.J.; Heinze, J.E.; Kernsmith, P.; Smith-Darden, J.; Fleming, P.J. Adolescent Risk of Dating Violence and Electronic Dating Abuse: A Latent Class Analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 50, 2472–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncy, E.A.; Sullivan, T.N.; Farrell, A.D.; Mehari, K.R.; Garthe, R.C. Identification of patterns of dating aggression and victimization among urban early adolescents and their relations to mental health symptoms. Psychol. Violence 2017, 7, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.M.; Goodman, L.A. Advocacy With Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: What It Is, What It Isn’t, and Why It’s Critically Important. Violence Against Women 2019, 25, 2007–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, J.; Craig, W.; Goldberg, A.; Pepler, D. Mixed-Gender Groups, Dating, and Romantic Relationships in Early Adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 2004, 14, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.P.; Delgado, A.O.; Gómez, Á.H. Violencia en relaciones de pareja de jóvenes y adolescentes. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2014, 46, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Garay, F.; Carrasco, M.Á.; Amor, P.J.; López-González, M.A. Factores asociados a la violencia en el noviazgo entre adolescentes: Una revisión crítica. Anu. Psicol. Jurid. 2015, 25, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, D.E.; Kearns, M.C.; Houry, D.; Valle, L.A.; Holland, K.M.; Marshall, K.J. Dating Violence and Injury among Youth Exposed to Violence. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20152627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.-J.; Buelga, S.; Tomás, I. Peer Victimization and Dating Violence Victimization: The Mediating Role of Loneliness, Depressed Mood, and Life Satisfaction. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 36, 2677–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, A.; Lanning, B.A.; Patterson, M.S. A Systematic Review of Dating Violence Risk Factors Among Undergraduate College Students. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 21, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Zafra, M.; Gómez-López, M.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Viejo, C. The association between dating violence victimization and the well-being of young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Violence 2024, 14, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.C.; Soto, D.A.; Manning, W.D.; Longmore, M.A. The characteristics of romantic relationships associated with teen dating violence. Soc. Sci. Res. 2010, 39, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blázquez-Alonso, M.; Moreno-Manso, J.M.; Sánchez ME, G.B.; Guerrero-Barona, E. La competencia emocional como recurso inhibidor para la perpetración del maltrato psicológico en la pareja. Salud Ment. 2012, 35, 287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, F.; Romera, E.M.; Viejo, C. Influencia de la auto-eficacia social y el apoyo social en la calidad de las relaciones de pareja adolescentes. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2015, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Furman, W.; Buhrmester, D. Methods and Measures: The Network of Relationships Inventory: Behavioral Systems Version. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, C.; Confalonieri, E.; Cuccì, G. The dimensions of uncertainty and ambiguity in adolescents and young adults’ romantic relationships: A systematic review. Ric. Di Psicol.-Open Access 2024, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi, F.S. Relationship of feelings of loneliness and depressive symptoms in old age: A study of older adults living with family and living alone. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2014, 5, 1428–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Dush CM, K.; Amato, P.R. Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2005, 22, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzer, B.; Kuiper, N.A. Humor use in romantic relationships: The effects of relationship satisfaction and pleasant versus conflict situations. J. Psychol. 2008, 142, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, J.; Steinberg, S.J.; Kachadourian, L.; Cobb, R.; Fincham, F. Romantic involvement and depressive symptoms in early and late adolescence: The role of a preoccupied relational style. Pers. Relatsh. 2004, 11, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Greca, A.M.; Harrison, H.M. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2005, 34, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Fernández, N.; Sánchez-Jiménez, V.; Rodríguez-deArriba, M.; Nacimiento-Rodríguez, L.; Elipe, P.; Del Rey, R. Traditional and cyber dating violence among adolescents: Profiles, prevalence, and short-term associations with peer violence. Aggress. Behav. 2022, 49, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J.; Herrero, J.; Rodríguez-Franco, L.; Bringas-Molleda, C.; Paíno-Quesada, S.G.; Pérez, B. Validation of Dating Violence QuestionNarie-R (DVQ-R). Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2017, 17, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viejo, C.; Rodríguez, C.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Sánchez-Zafra, M. Validation of DVQ questionarie: Agresión scale. 2024; in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Franco, L.; López-Cepero Borrego, J.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J.; Bringas-Molleda, C.; Antuña-Bellerín, M.D.L.Á.; Estrada-Pineda, C. Validation of the Dating Violence Questionnaire, DVQ (Cuestionario de Violencia entre Novios CUVINO) among Spanish-speaking youth: Analysis of results in Spain, Mexico and Argentina. Anu. De Psicol. Clin. Y De La Salud/Annu. Clin. Health Psychol. 2010, 6, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester, D.; Furman, W. The Network of Relationships Inventory: Relationship Qualities Version; Unpublished Measure; University of Texas at Dallas: Richardson, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen, L.K.; Muthen, B.O. MPlus, version 8.5, [Computer software]; Muthen y Muthen: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.L.; Muthén, B. Relating Latent Class Analysis Results to Variables not Included in the Analysis; University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pozueco, J.M.; Moreno, J.M.; Blázquez, M.; García-Baamonde, M.E. “psicópatas integrados/subclínicos en las relaciones de pareja: Perfil, maltrato psicológico y factores de riesgo.”/ integrated/sub-clinical psychopaths in relationships: Profile, psychological abuse and risk factors’. Papeles Del Psicólogo 2013, 34, 32–48. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=77825706004 (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Rey-Anacona, C. Prevalencia, factores de riesgo y problemáticas asociadas con la violencia en el noviazgo: Una revisión de la literatura. Av. En Psicol. Latinoam. 2008, 26, 227–241. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=79926209 (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Choi, H.J.; Weston, R.; Temple, J.R. A Three-Step latent class analysis to identify how different patterns of teen dating violence and psychosocial factors influence mental health. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 46, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, D.L.; Farhat, T.; Brooks-Russell, A.; Wang, J.; Barbieri, B.; Iannotti, R.J. Dating Violence Perpetration & Victimization among U.S. Adolescents: Prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, R.; Ortega-Rivera, J.A.; Sánchez, V. Violencia sexual entre compañeros y violencia en parejas adolescentes. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2008, 8, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera FJ, O.; Jiménez, V.S.; Ruiz, R.O. Violencia sexual y cortejo juvenil. In Agresividad Injustificada, Bullying y Violencia Escolar; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Gea, E.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Sánchez, V. Peer sexual harassment in adolescence: Dimensions of the sexual harassment survey in boys and girls. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Fuertes, A.; Fuertes, A. Agresión física y psicológica en las relaciones de noviazgo de adolescentes españoles: Motivos y consecuencias. Child Abus. Y Negl. 2010, 34, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, K.D.; Slep AM, S. A dyadic longitudinal model of adolescent dating aggression. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2003, 32, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viejo, C.; Toledano, N.; Gómez-López, M.; Ortega-Ruiz, R. Competencia para las relaciones romantices en el proceso de cortejo adolescente: Un estudio descriptivo. Inf. PsicolòGica/Inf. Psicològica 2022, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccì, G.; Davila, J.; Olivari, M.G.; Confalonieri, E. The Italian adaptation of the Romantic Competence Interview: A preliminary test of psychometrics properties. J. Relatsh. Res. 2020, 11, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povedano, A.; Estévez, E.; Martínez, B.; Monreal, M.-C. Un perfil psicosocial de adolescentes agresores y víctimas en la escuela: Análisis de las diferencias de género. Int. J. Soc. Psychol. Rev. De Psicol. Soc. 2012, 27, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Class Number | AIC | BIC | Log-Likelihood | Entrophy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 7575.796 | 7684.655 | 1.3074 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 3714.522 | 3827.746 | 3.4735 | 0.998 |

| 4 | 2872.825 | 3016.519 | 5.4392 | 0.998 |

| 5 | 2315.698 | 2489.872 | 5.4235 | 0.995 |

| Boys | Girls | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Non-involvement | 147 (63.9%) | 253 (75.7%) |

| Psychological–sexual involvement | 45 (19.6%) | 56 (16.8%) |

| Psychological–physical involvement | 13 (5.7%) | 16 (4.8%) |

| Mild concurrent violence | 10 (4.3%) | 5 (1.5%) |

| Severe concurrent involvement | 15 (6.5%) | 4 (1.2%) |

| Quality | Boys Separate Involvement | Girls Separate Involvement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | OR | β | OR | ||

| Non-involvement | Companionship | −0.059 | 0.943 | −0.365 | 0.952 |

| Intimate communication | −0.402 | 0.669 | −0.049 | 0.845 | |

| Emotional support | 0.205 | 1.227 | −0.168 | 0.964 | |

| Approval | −0.208 | 0.812 | −0.037 | 0.968 | |

| Satisfaction | 0.235 | 1.265 | −0.033 | 0.694 | |

| Conflict | 0.616 ** | 1.852 | −0.366 | 1.697 | |

| Criticism | −0.254 | 0.776 | 0.529 ** | 0.486 | |

| Pressure | 0.065 | 1.067 | −0.721 ** | 0.989 | |

| Exclusion | 0.083 | 1.087 | −0.011 | 1.535 | |

| Dominance | −0.008 | 0.992 | 0.429 | 1.364 | |

| Quality | Boys Separate Involvement | Girls Separate Involvement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | OR | β | OR | ||

| Non-involvement | Companionship | −0.089 | 0.914 | −0.869 | 0.419 |

| Intimate communication | 0.152 | 1.165 | 0.397 | 1.487 | |

| Emotional support | −0.841 * | 0.431 | −0.423 | 0.655 | |

| Approval | 0.338 | 1.402 | 0.461 | 1.585 | |

| Satisfaction | −0.018 | 0.982 | −0.539 | 1.715 | |

| Conflict | 0.710 * | 0.492 | −0.036 | 1.037 | |

| Criticism | 0.482 | 1.619 | 0.320 | 1.377 | |

| Pressure | 0.810 * | 2.249 | −0.202 ** | 0.817 | |

| Exclusion | −0.121 | 0.886 | −0.117 | 0.889 | |

| Dominance | −0.200 | 0.819 | 0.529 | 1.697 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Viejo, C.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Sánchez-Zafra, M. Dating Violence and the Quality of Relationships through Adolescence: A Longitudinal Latent Class Study. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100948

Viejo C, Ortega-Ruiz R, Sánchez-Zafra M. Dating Violence and the Quality of Relationships through Adolescence: A Longitudinal Latent Class Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):948. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100948

Chicago/Turabian StyleViejo, Carmen, Rosario Ortega-Ruiz, and María Sánchez-Zafra. 2024. "Dating Violence and the Quality of Relationships through Adolescence: A Longitudinal Latent Class Study" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100948

APA StyleViejo, C., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Sánchez-Zafra, M. (2024). Dating Violence and the Quality of Relationships through Adolescence: A Longitudinal Latent Class Study. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100948