The Moderating Role of the Five-Factor Model of Personality in the Relationship between Job Demands/Resources and Work Engagement: An Online Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

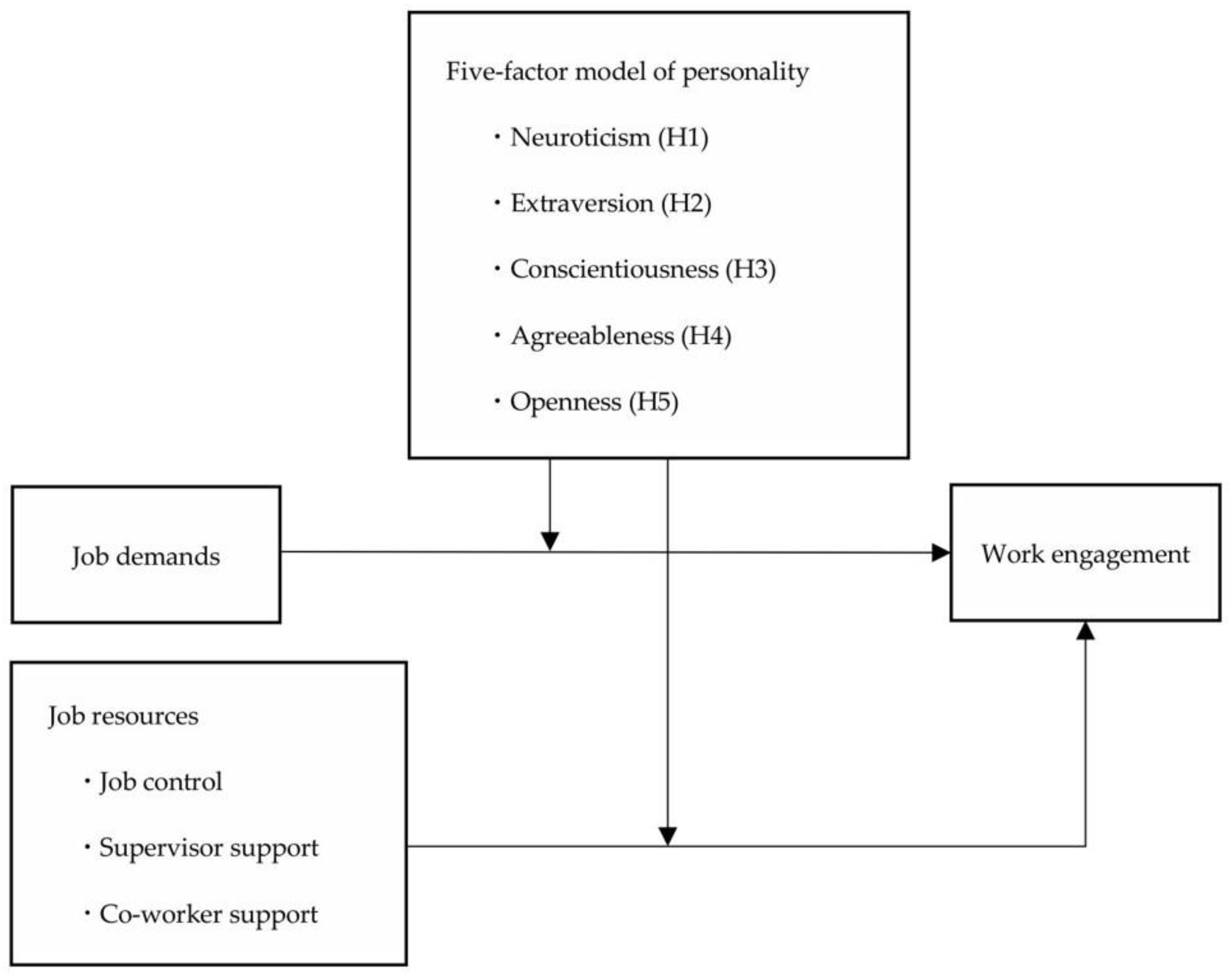

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Demographic Variables

2.2.2. Job Demands

2.2.3. Job Resources

2.2.4. Work Engagement

2.2.5. Personality Traits

2.3. Statistical Analysis

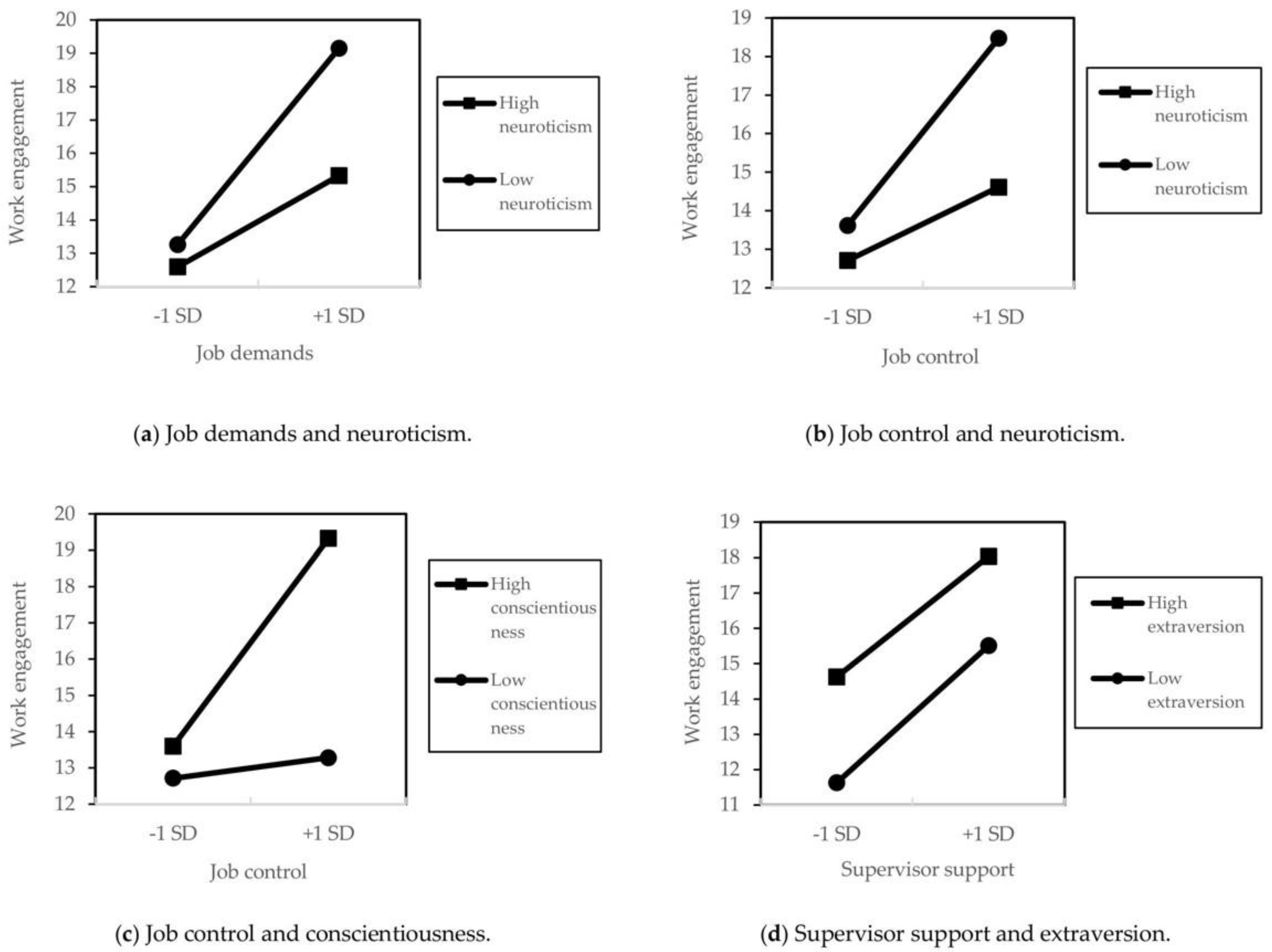

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S. Work engagement: Current trends. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B. A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Shirom, A.; Toker, S.; Berliner, S.; Shapira, I.; Melamed, S. The effects of physical fitness and feeling vigorous on self-rated health. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Bakker, A.B. Dr Jekyll or Mr. Hyde? On the Differences Between Work Engagement and Workaholism. In Research Companion to Working Time and Work Addiction; Burke, R.J., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kubota, K.; Kawakami, N. Do workaholism and work engagement predict employee well-being and performance in opposite directions? Ind. Health 2012, 50, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Ahola, K. The Job Demands-Resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work Stress 2008, 22, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Gevers, J.M.P. Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hayes, T.L. Business-unit–level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Shimazu, A.; Demerouti, E.; Shimada, K.; Kawakami, N. Work engagement versus workaholism: A test of the spillover-crossover model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 29, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Fujiwara, T.; Iwata, N.; Shimada, K.; Takahashi, M.; Tokita, M.; Watai, I.; Kawakami, N. Workaholism, work engagement and child well-being: A test of the spillover-crossover model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G.; Robledo, E.; Vignoli, M.; Topa, G.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work engagement: A meta-analysis using the job demands-resources model. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 126, 1069–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Patterson, M.; Dawson, J. Building work engagement: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, C.; Patterson, M.; Dawson, J. Work engagement interventions can be effective: A systematic review. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 348–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Leiter, M.P. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lesener, T.; Gusy, B.; Wolter, C. The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work Stress 2019, 33, 76–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Johnson, R.J.; Ennis, N.; Jackson, A.P. Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B. A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 1991, 44, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtz, G.M.; Donovan, J.J. Personality and job performance: The big five revisited. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langelaan, S.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Doornen, L.J.P.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement: Do individual differences make a difference? Pers. Individ. Dif. 2006, 40, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, K.; Rothmann, S. Work-related well-being in the South African police service. J. Crim. Justice 2006, 34, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Shin, K.H.; Swanger, N. Burnout and engagement: A comparative analysis using the big five personality dimensions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, H.R.; Glerum, D.R.; Wang, W.; Joseph, D.L. Who are the most engaged at work? A meta-analysis of personality and employee engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 1330–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuzaki, T.; Iwata, N. Association between the five-factor model of personality and work engagement: A meta-analysis. Ind. Health 2022, 60, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiotis, K.; Michaelides, G. Crossover of work engagement: The moderating role of agreeableness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, H.; De Zutter, P.; Geens, T.; Vogt, G.; Braeckman, L. Do personality traits determine work engagement? Results from a Belgian study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Bajpai, L. Linking conservation of resource perspective to personal growth initiative and intention to leave: Role of mediating variables. Pers. Rev. 2020, 50, 686–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, R.M.; van Vianen, A.E.M.; Bosle, C.; Fischer, J.E. Personality type matters: Perceptions of job demands, job resources, and their associations with work engagement and mental health. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 2576–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R. An alternative “description of personality”: The Big-Five factor structure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1216–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninomiya, K.; Ukiya, S.; Horike, K.; Ando, J.; Fujita, S.; Oshio, A.; Watanabe, Y. Handbook of Personality; Fukumura Shuppan, Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 2013. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt, F.; De Bolle, M.; McCrae, R.R.; Terracciano, A.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Collaborators of the Adolescent Personality Profiles of Cultures Project. Assessing the universal structure of personality in early adolescence: The NEO-PI-R and NEO-PI-3 in 24 cultures. Assessment 2009, 16, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T.; Martin, T.A.; Oryol, V.E.; Rukavishnikov, A.A.; Senin, I.G.; Hřebíčková, M.; Urbánek, T. Consensual validation of personality traits across cultures. J. Res. Pers. 2004, 38, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Terracciano, A.; Personality Profiles of Cultures Project. Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: Data from 50 cultures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tackett, J.L.; Lahey, B.B. Neuroticism. In The Oxford Handbook of the Five Factor; Widiger, T.A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, C.J. How replicable are links between personality traits and consequential life outcomes? The life outcomes of personality replication project. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Four ways five factors are basic. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1992, 13, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, D. Personality: What Makes You the Way You Are; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, A. Agreeableness. In Encyclopedia of Psychology; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.F.; Steelman, L.A. Marrying personality and job resources and their effect on engagement via critical psychological states. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 797–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vianen, A.E.M. Person–environment fit: A review of its basic tenets. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; van Woerkom, M. Strengths use in organizations: A positive approach of occupational health. Can. Psychol. 2018, 59, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, J.J.; McLaney, M.A. Exposure to job stress: A new psychometric instrument. Scan. J. Work Environ. Health. 1988, 14, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E.; O’Connell, B.J. The contribution of personality traits, negative affectivity, locus of control and Type A to the subsequent reports of job stressors and job strains. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1994, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Chen, P.Y.; O’Connell, B.J. A longitudinal study of relations between job stressors and job strains while controlling for prior negative affectivity and strains. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.W.; DeNunzio, M.M. Examining personality—Job characteristic interactions in explaining work outcomes. J. Res. Pers. 2020, 84, 103884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, T.; De Caluwé, E.; Bogaerts, S. Personality moderators of the cross-sectional relationship between job demands and both burnout and work engagement in judges: The boosting effects of conscientiousness and introversion. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2023, 89, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuzaki, T.; Iwata, N. The impact of negative and positive affectivity on the relationship between work-related psychological factors and work engagement in Japanese workers: A comparison of psychological distress. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.V.; Hall, E.M. Job strain, workplace social support, and cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am. J. Public Health 1988, 78, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E. Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—Self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—With job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.; Eschleman, K.J.; Bowling, N.A. Relationship between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work Stress 2009, 23, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Stewart, G.L.; Piotrowski, M. Personality and job performance: Test of the mediating effects of motivation among sales representatives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, B.H.; Baur, J.E.; Banford, C.G.; Postlethwaite, B.E. Team players and collective performance: How agreeableness affects team performance over time. Small Group Res. 2013, 44, 680–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, G.J. A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 2, 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Population Estimates. 2021. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2021np/index.html (accessed on 18 November 2022). (In Japanese).

- Maniaci, M.R.; Rogge, R.D. Caring about carelessness: Participant inattention and its effects on research. J. Res. Pers. 2014, 48, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomitsu, T.; Haratani, T.; Nakamura, K.; Kawakami, N.; Hayashi, T.; Hiro, H.; Arai, M.; Miyazaki, S.; Furuki, K.; Ohya, Y.; et al. Final development of the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire mainly used for assessment of the individuals. In The Ministry of Labor Sponsored Grant for the Prevention of Work-Related Illness; Kato, M., Ed.; Ministry of Labor: Tokyo, Japan, 2000; pp. 126–164. Available online: http://www.tmu-ph.ac/news/data/H11report.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021). (In Japanese)

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Download site for the “Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare Stress Check Program”. Available online: https://stresscheck.mhlw.go.jp/material.html (accessed on 23 September 2024). (In Japanese).

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kosugi, S.; Suzuki, A.; Nashiwa, H.; Kato, A.; Sakamoto, M.; Irimajiri, H.; Amano, S.; Hirohata, K.; et al. Work engagement in Japan: Validation of the Japanese version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2008, 57, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namikawa, T.; Tani, I.; Wakita, T.; Kumagai, R.; Nakane, A.; Noguchi, H. Development of a short form of the Japanese Big-Five Scale, and a test of its reliability and validity. Jpn. J. Psychol. 2012, 83, 91–99. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, H.G.; Heilbrun, A.B. The Adjective Check List Manual, 1983 ed.; Consulting Psychologist Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, S. Construction of the Big Five Scales of personality trait terms and concurrent validity with NPI. Jpn. J. Psychol. 1996, 67, 61–67. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B. The gain spiral of resources and work engagement: Sustaining a positive work life. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 118–131. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.A. Personality dimensions and emotion systems. In The Nature of Emotion; Ekman, P., Davidson, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 329–331. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C. The dispositional causes of job satisfaction: A core evaluations approach. Res. Organ. Behav. 1997, 19, 151–188. [Google Scholar]

- Chiorri, C.; Garbarino, S.; Bracco, F.; Magnavita, N. Personality traits moderate the effect of workload sources on perceived workload in flying column police officers. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, S.; Chiorri, C.; Magnavita, N. Personality traits of the five-factor model are associated with work-related stress in special force police officers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2014, 87, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mierlo, H.; Bakker, A.B. Crossover of engagement in groups. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H. Personality change via work: A job demand–control model of Big-Five personality changes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 92, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, A.L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, K.; Morrison, H.M.; Jorgensen, D.F. Trait expression through perceived job characteristics: A meta-analytic path model linking personality and job attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A.; Feldt, T.; Kinnunen, U.; Mauno, S. Does personality matter? A review of individual differences in occupational well-being. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Bakker, A.B., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2013; pp. 107–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, M.A.; Boswell, W.R.; Roehling, M.V.; Boudreau, J.W. An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 757 | 50.5 |

| Women | 743 | 49.5 |

| Age (years) | 45.7 1 | 12.9 2 |

| Education | ||

| University/graduate school graduate | 873 | 58.2 |

| Vocational school/college graduate | 354 | 23.6 |

| High school graduate | 263 | 17.5 |

| Others | 10 | 0.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 488 | 32.5 |

| Married | 833 | 55.5 |

| Divorce/bereavement | 179 | 11.9 |

| Number of children | ||

| 0 | 708 | 47.2 |

| 1 | 265 | 17.7 |

| 2 | 362 | 24.1 |

| 3≥ | 165 | 11.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Manager | 237 | 15.8 |

| Non-manual worker | 1057 | 70.5 |

| Manual worker | 78 | 5.2 |

| Other | 128 | 8.5 |

| Career in the current job (years) | 13.8 1 | 11.5 2 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 45.7 | 12.9 | ― | |||||||||||

| 2. Career in the current job | 13.8 | 11.5 | 0.55 *** | ― | ||||||||||

| 3. Job demands | 16.4 | 4.0 | −0.08 ** | −0.03 | (0.87) | |||||||||

| 4. Job control | 8.0 | 2.1 | 0.13 *** | 0.11 *** | −0.01 | (0.79) | ||||||||

| 5. Supervisor support | 7.4 | 2.4 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.30 *** | (0.90) | |||||||

| 6. Co-worker support | 7.8 | 2.3 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 * | 0.24 *** | 0.69 *** | (0.88) | ||||||

| 7. Work engagement | 22.1 | 12.4 | 0.21 *** | 0.09 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.30 *** | (0.97) | |||||

| 8. Neuroticism | 16.1 | 3.9 | −0.21 *** | −0.08 ** | 0.19 *** | −0.17 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.24 *** | (0.84) | ||||

| 9. Extraversion | 15.4 | 3.8 | 0.09 *** | 0.02 | 0.06 * | 0.20 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.30 *** | −0.26 *** | (0.84) | |||

| 10. Conscientiousness | 22.4 | 4.5 | 0.25 *** | 0.09 *** | −0.02 | 0.12 *** | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.28 *** | −0.29 *** | 0.07 * | (0.79) | ||

| 11. Agreeableness | 19.3 | 3.6 | 0.12 *** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.14 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.27 *** | −0.27 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.35 *** | (0.75) | |

| 12. Openness | 18.2 | 3.9 | 0.09 *** | 0.01 | 0.08 ** | 0.23 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.25 *** | −0.12 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.26 *** | (0.81) |

| B 1 | 95%CI 2 | β 3 | ΔR2 4 | Adjusted R2 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 0.05 | 0.04 *** | |||

| Age | 0.13 | 0.08–0.18 | 0.13 *** | ||

| Gender (0 = Men, 1 = Women) | 1.14 | 0.05–2.23 | 0.05 * | ||

| Career in the current job | −0.01 | −0.07–0.04 | −0.01 | ||

| Step 2 | 0.17 *** | 0.22 *** | |||

| Job demands | 0.52 | 0.38–0.65 | 0.17 *** | ||

| Job control | 0.71 | 0.44–0.99 | 0.12 *** | ||

| Supervisor support | 0.76 | 0.45–1.08 | 0.15 *** | ||

| Co-worker support | 0.39 | 0.06–0.72 | 0.07 * | ||

| Step 3 | 0.08 *** | 0.30 *** | |||

| Neuroticism | −0.28 | −0.43–(−0.13) | −0.09 *** | ||

| Extraversion | 0.35 | 0.18–0.53 | 0.11 *** | ||

| Conscientiousness | 0.38 | 0.25–0.52 | 0.14 *** | ||

| Agreeableness | 0.26 | 0.10–0.43 | 0.08 ** | ||

| Openness | 0.19 | 0.02–0.35 | 0.06 * | ||

| Step 4 | 0.01 * | 0.30 *** | |||

| Job demands × Neuroticism | −0.04 | −0.07–(−0.01) | −0.05 * | ||

| Job demands × Extraversion | −0.00 | −0.05–0.04 | −0.01 | ||

| Job demands × Conscientiousness | 0.03 | −0.00–0.06 | 0.04 | ||

| Job demands × Agreeableness | −0.02 | −0.06–0.02 | −0.02 | ||

| Job demands × Openness | 0.01 | −0.03–0.04 | 0.01 | ||

| Step 5 | 0.02 *** | 0.31 *** | |||

| Job control × Neuroticism | −0.07 | −0.14–(−0.00) | −0.05 * | ||

| Job control × Extraversion | −0.01 | −0.09–0.07 | −0.01 | ||

| Job control × Conscientiousness | 0.11 | 0.05–0.18 | 0.10 *** | ||

| Job control × Agreeableness | −0.01 | −0.09–0.07 | −0.01 | ||

| Job control × Openness | −0.02 | −0.09–0.05 | −0.02 | ||

| Supervisor support × Neuroticism | 0.04 | −0.04–0.12 | 0.04 | ||

| Supervisor support × Extraversion | −0.10 | −0.20–(−0.01) | −0.08 * | ||

| Supervisor support × Conscientiousness | 0.05 | −0.02–0.12 | 0.05 | ||

| Supervisor support × Agreeableness | 0.04 | −0.05–0.13 | 0.03 | ||

| Supervisor support × Openness | −0.01 | −0.09–0.08 | −0.01 | ||

| Co-worker support × Neuroticism | −0.01 | −0.10–0.07 | −0.01 | ||

| Co-worker support × Extraversion | 0.08 | −0.02–0.18 | 0.06 | ||

| Co-worker support × Conscientiousness | 0.00 | −0.07–0.08 | 0.00 | ||

| Co-worker support × Agreeableness | −0.08 | −0.17–0.02 | −0.06 | ||

| Co-worker support × Openness | 0.06 | −0.03–0.15 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fukuzaki, T.; Iwata, N. The Moderating Role of the Five-Factor Model of Personality in the Relationship between Job Demands/Resources and Work Engagement: An Online Cross-Sectional Study. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100936

Fukuzaki T, Iwata N. The Moderating Role of the Five-Factor Model of Personality in the Relationship between Job Demands/Resources and Work Engagement: An Online Cross-Sectional Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):936. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100936

Chicago/Turabian StyleFukuzaki, Toshiki, and Noboru Iwata. 2024. "The Moderating Role of the Five-Factor Model of Personality in the Relationship between Job Demands/Resources and Work Engagement: An Online Cross-Sectional Study" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100936

APA StyleFukuzaki, T., & Iwata, N. (2024). The Moderating Role of the Five-Factor Model of Personality in the Relationship between Job Demands/Resources and Work Engagement: An Online Cross-Sectional Study. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100936