The Antecedents and Outcomes of Public Service Motivation: A Meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands–Resources Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

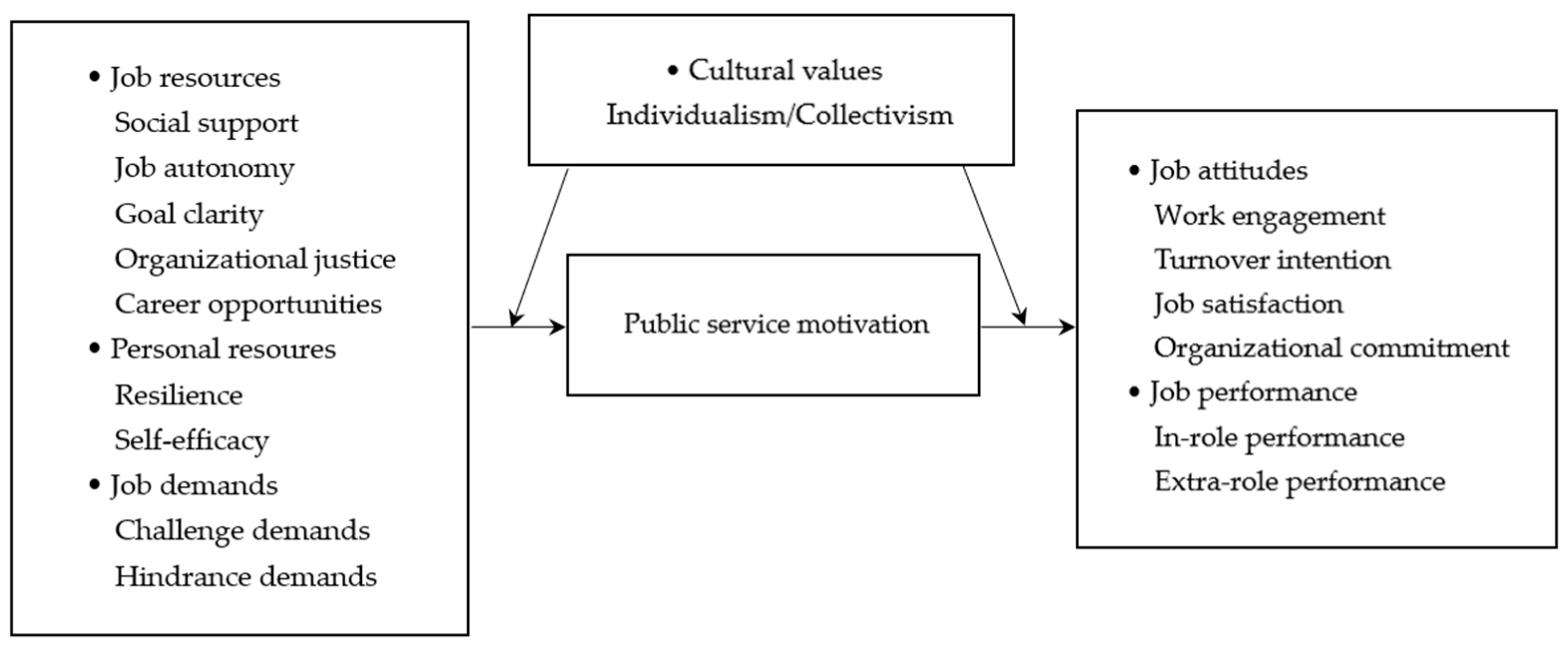

2. Theoretical Basis and Model Construction

2.1. Antecedents of PSM

2.2. Outcomes of PSM

2.3. Culture Values as Moderators

3. Materials and Methods

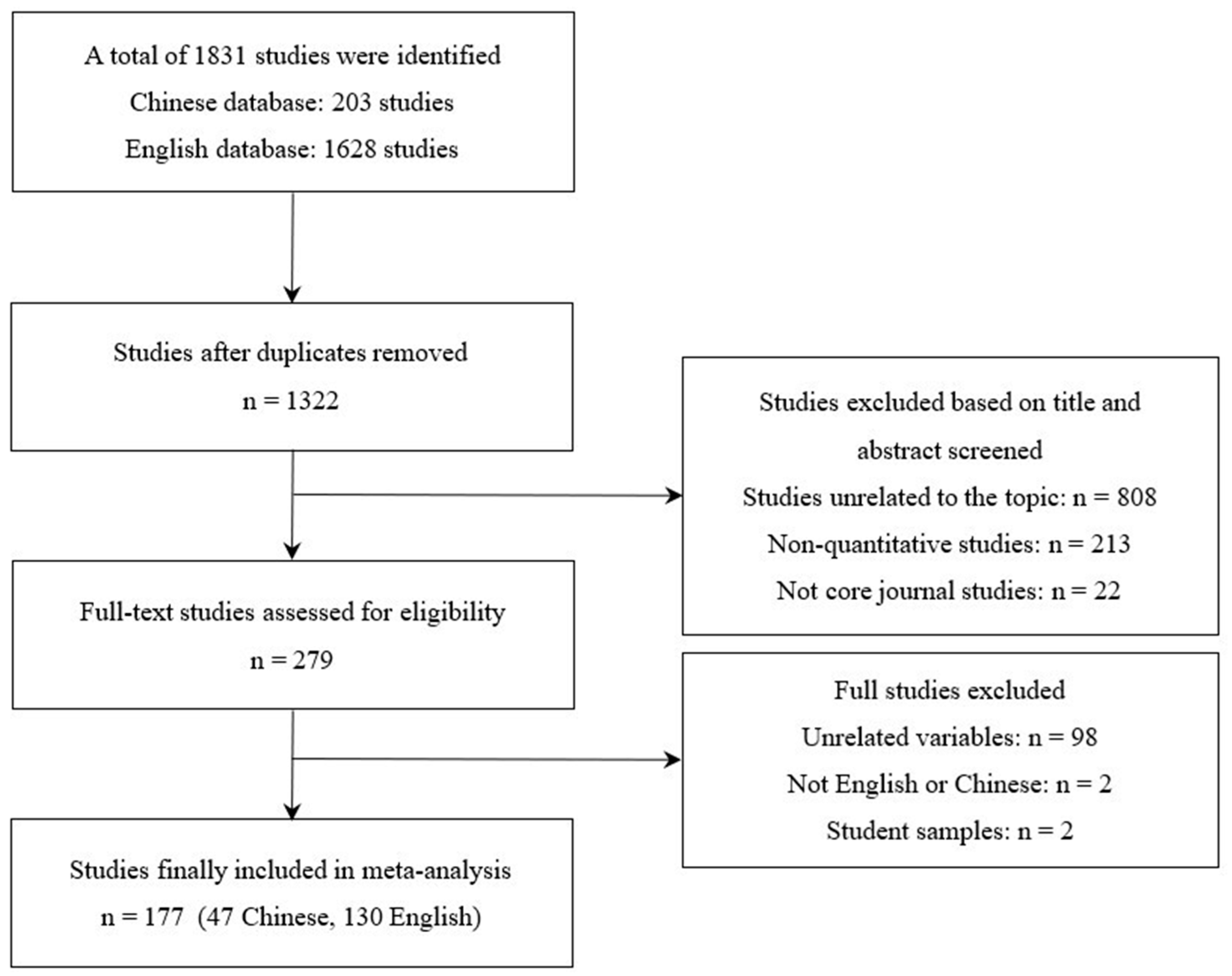

3.1. Literature Search and Screening

3.2. Coding Procedure

3.3. Meta-Analytic Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Main Effects

4.2. Moderating Effects

4.3. Publication Bias Tests

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Effects of Antecedents

5.2. Main Effects of Outcomes

5.3. Moderating Effects of Individualism/Collectivism

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perry, J.L.; Wise, L.R. The Motivational Bases of Public Service. Public Adm. Rev. 1990, 50, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.L. Measuring Public Service Motivation: An Assessment of Construct Reliability and Validity. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1996, 6, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisink, P.; Steijn, B. Public Service Motivation and Job Performance of Public Sector Employees in the Netherlands. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2009, 75, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.E.; Christensen, R.K.; Pandey, S.K. Measuring Public Service Motivation: Exploring the Equivalence of Existing Global Measures. Int. Public Manag. J. 2013, 16, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, T. How Does Social Support Affect Public Service Motivation of Healthcare Workers in China: The Mediating Effect of Job Stress. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uluturk, B.; Yilmaz Altuntas, E.; Isik, T. Impact of Ethical Leadership on Job Satisfaction and Work-Related Burnout among Turkish Street-Level Bureaucrats: The Roles of Public Service Motivation, Perceived Organizational Support, and Red Tape. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2023, 46, 1502–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G. Does Public Service Motivation Mediate the Relationship between Goal Clarity and Both Organizational Commitment and Extra-Role Behaviours? Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-W. Moderators of the Motivational Effects of Performance Management: A Comprehensive Exploration Based on Expectancy Theory. Public Pers. Manag. 2019, 48, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, H.R.; Harari, M.B.; Herst, D.E.L.; Prysmakova, P. Demographic Determinants of Public Service Motivation: A Meta-Analysis of PSM-Age and -Gender Relationships. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 1397–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Wang, C. Can Public Service Motivation Increase Work Engagement?—A Meta-Analysis across Cultures. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1060941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Perry, J.L. The Psychological Mechanisms of Public Service Motivation: A Two-Wave Examination. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2016, 36, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G. Towards a Better Understanding of Public Service Motivation and Mission Valence in Public Agencies. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1217–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-R. Public Service Motivation and Proactive Behavioral Responses to Change: A Three-Way Interaction. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2021, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homberg, F.; McCarthy, D.; Tabvuma, V. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between Public Service Motivation and Job Satisfaction. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Blalock, E.C.; Lyu, X. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Public Service Motivation and Individual Job Performance: Cross-Validating the Effect of Culture. Int. Public Manag. J. 2022, 25, 1115–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, K.P.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Q. Public Service Motivation and Turnover Intention: Testing the Mediating Effects of Job Attitudes. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Zhong, W. Public Service Motivation Matters: Examining the Differential Effects of Challenge and Hindrance Stressors on Organizational Identification and Turnover Intention. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 545–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.E.; Schmidt, F.L. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; De Cuyper, N.; De Witte, H.; Vansteenkiste, M. Not All Job Demands Are Equal: Differentiating Job Hindrances and Job Challenges in the Job Demands–Resources Model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2010, 19, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, U.T.; Bro, L.L. How Transformational Leadership Supports Intrinsic Motivation and Public Service Motivation: The Mediating Role of Basic Need Satisfaction. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2018, 48, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wu, Z.; Ma, M.; Zang, Z.; Yang, T. How Stress Affects Presenteeism in Public Sectors: A Dual Path Analysis of Chinese Healthcare Workers. J. Public Health 2022, 30, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürstenberg, N.; Alfes, K.; Kearney, E. How and When Paradoxical Leadership Benefits Work Engagement: The Role of Goal Clarity and Work Autonomy. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 94, 672–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G.; Robledo, E.; Vignoli, M.; Topa, G.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. Work Engagement: A Meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands-Resources Model. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 126, 1069–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory in Work Organizations: The State of a Science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Vallerand, R.J. The Effects of Work Motivation on Employee Exhaustion and Commitment: An Extension of the JD-R Model. Work Stress 2012, 26, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Guo, Q.; Ma, B.; Zhang, S.; Sun, P. Bridging Personality and Online Prosocial Behavior: The Roles of Empathy, Moral Identity, and Social Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 575053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, R.B.; Bodine, A.J.; Gibbs, J.C.; Basinger, K.S. What Accounts for Prosocial Behavior? Roles of Moral Identity, Moral Judgment, and Self-Efficacy Beliefs. J. Genet. Psychol. 2018, 179, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, S.; Kaufman, M.R.; Zhang, X.; Xia, S.; Niu, C.; Zhou, R.; Xu, W. Resilience and Prosocial Behavior among Chinese University Students During COVID-19 Mitigation: Testing Mediation and Moderation Models of Social Support. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 1531–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, J.B.; Judge, T.A. Can “Good” Stressors Spark “Bad” Behaviors? The Mediating Role of Emotions in Links of Challenge and Hindrance Stressors with Citizenship and Counterproductive Behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepine, J.A.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Lepine, M.A. A Meta-Analytic Test of the Challenge Stressor-Hindrance Stressor Framework: An Explanation for Inconsistent Relationships among Stressors and Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective Events Theory: A Theoretical Discussion of the Structure, Causes and Consequences of Affective Experiences at Work. In Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews; Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L., Eds.; Elsevier Science/JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1996; Volume 18, pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Lee, H.; Xu, D. Challenge Stressors, Work Engagement, and Affective Commitment among Chinese Public Servants. Public Pers. Manag. 2020, 49, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential Challenge Stressor-Hindrance Stressor Relationships with Job Attitudes, Turnover Intentions, Turnover, and Withdrawal Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S. An Emotion-Centered Model of Voluntary Work Behavior: Some Parallels between Counterproductive Work Behavior and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, J.; Sohn, Y.W.; Lim, J.I. Perceived Overqualification, Boredom, and Extra-Role Behaviors: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. J. Career Dev. 2021, 48, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D. Job Attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 341–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswesvaran, C.; Ones, D.S. Perspectives on models of job performance. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2000, 8, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-S.; Park, T.-Y.; Koo, B. Identifying Organizational Identification as a Basis for Attitudes and Behaviors: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.B.; Kjeldsen, A.M. Public Service Motivation, User Orientation, and Job Satisfaction: A Question of Employment Sector? Int. Public Manag. J. 2013, 16, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Cho, I.K.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.; Choi, J.M.; Kim, J.; Kim, C.; Yoo, S.; Chung, S. Mediating Effect of Public Service Motivation and Resilience on the Association between Work-related Stress and Work Engagement of Public Workers in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Investig. 2022, 19, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Does Person-Organization Fit Matter in the Public-Sector? Testing the Mediating Effect of Person-Organization Fit in the Relationship between Public Service Motivation and Work Attitudes. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. The Causal Relation between Job Attitudes and Performance: A Meta-Analysis of Panel Studies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, G.; Eva, N.; Newman, A. Can Public Leadership Increase Public Service Motivation and Job Performance? Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 80, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.W.; Im, T. PSM and Turnover Intention in Public Organizations: Does Change-Oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior Play a Role? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2016, 36, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattrie, L.T.B.; Kittler, M.G.; Paul, K.I. Culture, Burnout, and Engagement: A Meta-Analysis on National Cultural Values as Moderators in JD-R Theory. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2020, 69, 176–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycan, Z.; Kanungo, R.N.; Sinha, J.B. Organizational Culture and Human Resource Management Practices: The Model of Culture Fit. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1999, 30, 501–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. The Cultural Relativity of Organizational Practices and Theories. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1983, 14, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. National Culture and Public Service Motivation: Investigating the Relationship Using Hofstede’s Five Cultural Dimensions. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 83, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockstuhl, T.; Eisenberger, R.; Shore, L.M.; Kurtessis, J.N.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Salar, M. Perceived Organizational Support (POS) Across 54 Nations: A Cross-Cultural Meta-Analysis of POS Effects. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 933–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Lu, L.; Eisenberger, R.; Fosh, P. Effects of Leader–Member Exchange and Workload on Presenteeism. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A. Challenge and Hindrance Demands Lead to Employees’ Health and Behaviours Through Intrinsic Motivation. Stress Health 2018, 34, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, C. The Relationship between Acculturation, Individualism/Collectivism, and Job Attribute Preferences for Hispanic MBAs. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M.; Lawler, J. Cultural Values as Moderators of Employee Reactions to Job Insecurity: The Role of Individualism and Collectivism. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2006, 55, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, M.B.; Williams, E.A.; Castro, S.L.; Brant, K.K. Self-Leadership: A Meta-Analysis of Over Two Decades of Research. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 94, 890–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiernik, B.M.; Dahlke, J.A. Obtaining Unbiased Results in Meta-Analysis: The Importance of Correcting for Statistical Artifacts. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 3, 94–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Piatak, J.S. Public Service Motivation, Prosocial Behaviours, and Career Ambitions. Int. J. Manpow. 2016, 37, 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, M.L.; Royal, M.A. Breaking Engagement Apart: The Role of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation in Engagement Strategies. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 10, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Yahui, S.; Xiao, L. Undermining Effect Exists or Not: Relationship between Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation in Workplace. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2016, 48, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, A.J.; Biggs, A.; Hegerty, E. Work Engagement: Investigating the Role of Transformational Leadership, Job Resources, and Recovery. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 2017, 151, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B. A Resource Perspective on the Work–Home Interface: The Work–Home Resources Model. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, K.; Yu, W. Work-Related Stressors and Health-Related Outcomes in Public Service: Examining the Role of Public Service Motivation. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2015, 45, 653–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnenluecke, M.K. Resilience in Business and Management Research: A Review of Influential Publications and a Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, T.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.P. The Effect of Resilience and Self-Efficacy on Nurses’ Compassion Fatigue: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 2030–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, M.A.; Boswell, W.R.; Roehling, M.V.; Boudreau, J.W. An Empirical Examination of Self-Reported Work Stress among U.S. Managers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Choking Under Pressure: Self-Consciousness and Paradoxical Effects of Incentives on Skillful Performance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, C.; Li, H. Leading Poorly under Challenge Stress? Indirect Influence of Team Leader’s Challenge Stress on Subordinates’ Creativity. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; LePine, J.A.; Buckman, B.R.; Wei, F. It’s Not Fair… Or Is It? The Role of Justice and Leadership in Explaining Work Stressor–Job Performance Relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, J.J.; Disselhorst, R. Should We Be “Challenging” Employees?: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis of the Challenge-Hindrance Model of Stress. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould-Williams, J.S.; Mostafa, A.M.; Bottomley, P.A. Public Service Motivation and Employee Outcomes in the Egyptian Public Sector: Testing the Mediating Effect of Person-Organization Fit. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Chen, H. “Bite the Bullet?”—The Influence of Job Stress on Turnover Intention: The Chain Mediating Role of Organization-Based Self-Esteem and Resilience. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 11360–11372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Howard, J.L.; Van Vaerenbergh, Y.; Leroy, H.; Gagné, M. Beyond Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: A Meta-Analysis on Self-Determination Theory’s Multidimensional Conceptualization of Work Motivation. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 11, 240–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. Factor Analysis of the General Self-Efficacy Scale and Its Relationship with Individualism/Collectivism among Twenty-Five Countries: Application of Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lu, H.; Li, P.; van der Linden, D.; Bakker, A.B. Antecedents and Outcomes of Work-Related Flow: A Meta-Analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2023, 144, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.C.; Cheng, Y. Psychosocial Work Hazards, Self-Rated Health and Burnout: A Comparison Study of Public and Private Sector Employees. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e193–e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golembiewski, R.T.; Boudreau, R.A.; Sun, B.-C.; Luo, H. Estimates of Burnout in Public Agencies: Worldwide, How Many Employees Have Which Degrees of Burnout, and with What Consequences? Public Adm. Rev. 1998, 58, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lan, Y.; Li, C. Challenge-Hindrance Stressors and Innovation: A Meta-Analysis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 4, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | K | N | SDρ | 95% CI | 80% CV | %VAR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job resources | 49 | 43,208 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.20 | [0.24, 0.36] | [0.03, 0.57] | 4.24 |

| Social support | 16 | 9049 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.23 | [0.26, 0.51] | [0.08, 0.68] | 5.05 |

| Job autonomy | 7 | 6740 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.07 | [0.12, 0.26] | [0.10, 0.29] | 27.21 |

| Goal clarity | 12 | 13,271 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.23 | [0.20, 0.50] | [0.04, 0.66] | 3.06 |

| Organizational justice | 10 | 9496 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.20 | [0.15, 0.44] | [0.01, 0.57] | 4.08 |

| Career opportunities | 4 | 4652 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.15 | [−0.08, 0.41] | [−0.08, 0.41] | 5.65 |

| Personal resources | 11 | 5757 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.19 | [0.30, 0.57] | [0.17, 0.70] | 6.58 |

| Resilience | 5 | 3408 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.18 | [0.27, 0.73] | [0.23, 0.78] | 6.44 |

| Self-efficacy | 6 | 2349 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.19 | [0.12, 0.55] | [0.05, 0.62] | 8.46 |

| Job demands | ||||||||

| Challenge demands | 19 | 19,001 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.16 | [−0.10, 0.06] | [−0.23, 0.19] | 5.06 |

| Hindrance demands | 30 | 40,822 | −0.12 | −0.15 | 0.23 | [−0.24, −0.06] | [−0.45, 0.15] | 2.15 |

| Variables | K | N | SDρ | 95% CI | 80% CV | %VAR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job attitudes | 127 | 147,272 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.24 | [0.33, 0.41] | [0.06, 0.68] | 2.82 |

| Work engagement | 21 | 23,565 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.10 | [0.56, 0.66] | [0.47, 0.74] | 18.60 |

| Turnover intention | 20 | 23,382 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.16 | [−0.14, 0.01] | [−0.28, 0.15] | 4.70 |

| Job satisfaction | 59 | 47,840 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.20 | [0.26, 0.37] | [0.06, 0.57] | 5.09 |

| Org. commitment | 27 | 52,485 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.19 | [0.37, 0.52] | [0.20, 0.69] | 3.96 |

| Job performance | 83 | 53,345 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.21 | [0.46, 0.56] | [0.24, 0.78] | 5.97 |

| In-role performance | 22 | 16,539 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.21 | [0.33, 0.52] | [0.15, 0.70] | 5.18 |

| Extra-role performance | 61 | 36,806 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.20 | [0.50, 0.60] | [0.29, 0.81] | 6.88 |

| Variables | Subgroup | K | N | SDρ | 95% CI | 80% CV | ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job resources | Individualism | 16 | 21,595 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.09 | [0.10, 0.20] | [0.03, 0.28] | F (1, 46.02) = 55.90 *** |

| Collectivism | 33 | 21,613 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.17 | [0.39, 0.51] | [0.22, 0.68] | ||

| Personal resources | Individualism | 3 | 1964 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.16 | [−0.06, 0.78] | [0.05, 0.67] | F (1, 4.71) = 0.08 |

| Collectivism | 8 | 3793 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.21 | [0.29, 0.65] | [0.17, 0.77] | ||

| Challenge demands | Individualism | 2 | 2107 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.21 | [−1.97, 1.93] | [−0.68, 0.64] | F (1, 1.14) = 0.00 |

| Collectivism | 17 | 16,894 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.16 | [−0.10, 0.07] | [−0.23, 0.20] | ||

| Hindrance dmands | Individualism | 10 | 20,303 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.06, −0.01] | [−0.06, −0.01] | F (1, 19.96) = 12.12 ** |

| Collectivism | 20 | 20,519 | −0.21 | −0.26 | 0.28 | [−0.39, −0.13] | [−0.64, 0.11] | ||

| Job attitudes | Individualism | 43 | 83,700 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.21 | [0.22, 0.34] | [0.01, 0.55] | F (1, 95.31) = 26.28 *** |

| Collectivism | 83 | 62,655 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.23 | [0.44, 0.54] | [0.19, 0.79] | ||

| Job performance | Individualism | 18 | 16,389 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.15 | [0.26, 0.42] | [0.14, 0.54] | F (1, 32.82) = 30.66 *** |

| Collectivism | 65 | 36,956 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.19 | [0.54, 0.64] | [0.34, 0.83] |

| Variables | 5K + 10 | Nfs | Begg’s Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tau | p | |||

| Job resources | 255 | 46,014 | 0.08 | 0.41 |

| Social support | 90 | 5545 | −0.05 | 0.82 |

| Job autonomy | 45 | 307 | 0.14 | 0.77 |

| Goal clarity | 70 | 3967 | 0.12 | 0.64 |

| Organizational justice | 60 | 2090 | −0.07 | 0.86 |

| Career opportunities | 30 | - | 0.33 | 0.75 |

| Personal resources | 65 | 3381 | −0.05 | 0.88 |

| Resilience | 35 | 1400 | 0.20 | 0.82 |

| Self-efficacy | 40 | 425 | −0.20 | 0.72 |

| Job demands | ||||

| Challenge demands | 105 | - | 0.27 | 0.11 |

| Hindrance demands | 160 | 4325 | −0.16 | 0.20 |

| Job attitudes | 645 | 552,993 | −0.09 | 0.12 |

| Work engagement | 115 | 32,498 | −0.11 | 0.51 |

| Turnover intention | 110 | - | 0.19 | 0.26 |

| Job satisfaction | 305 | 76,194 | −0.06 | 0.53 |

| Org. commitment | 145 | 62,062 | −0.08 | 0.56 |

| Job performance | 425 | 316,323 | −0.02 | 0.79 |

| In-role performance | 120 | 13,933 | −0.01 | 0.96 |

| Extra-role performance | 310 | 197,404 | 0.05 | 0.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, H.; An, S.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X. The Antecedents and Outcomes of Public Service Motivation: A Meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands–Resources Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100861

Tang H, An S, Zhang L, Xiao Y, Li X. The Antecedents and Outcomes of Public Service Motivation: A Meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands–Resources Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(10):861. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100861

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Hanyu, Shiwen An, Luoyi Zhang, Yun Xiao, and Xia Li. 2024. "The Antecedents and Outcomes of Public Service Motivation: A Meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands–Resources Model" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 10: 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100861

APA StyleTang, H., An, S., Zhang, L., Xiao, Y., & Li, X. (2024). The Antecedents and Outcomes of Public Service Motivation: A Meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands–Resources Model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14100861