Compassion Catalysts: Unveiling Proactive Pathways to Job Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

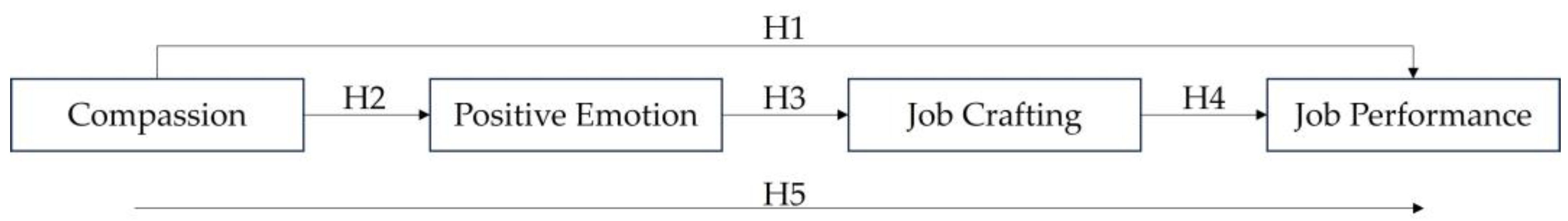

2. Hypotheses Development

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Testing of Common Method Bias

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Instrument and Measurement Scales

- Compassion

- I frequently experience compassion on the job.

- I frequently experience compassion from my supervisor.

- I frequently experience compassion my co-workers.

- Positive Emotion

- I often feel proud within the organization.

- I often feel grateful within the organization.

- I often feel inspired within the organization.

- I often feel at ease within the organization.

- Job Crafting

- I often make constructive suggestions for improving how things operate within the organization.

- I often try to implement solutions pressing organizational problems.

- I often try to introduce new structures, technologies, or approaches to improve efficiency.

- I often try to institute new work methods that are more effective for the company.

- Job Performance

- I adequately complete assigned duties.

- I fulfill responsibilities specified in job description.

- I meet formal performance requirements of the job.

- I engage in activities that will directly affect his/her performance evaluation.

- I perform task that are expected of him/her.

References

- Kanov, J. Why suffering matters! J. Manag. Inq. 2021, 30, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Workman, K.M.; Hardin, A.E. Compassion at work. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Worline, M.C.; Frost, P.J.; Lilius, J.M. Explaining compassion organizing. Adm. Sci. Q. 2006, 51, 59–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, P.J. Why compassion counts! J. Manag. Inq. 1999, 8, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilius, J.M.; Worline, M.C.; Maitlis, S.; Kanov, J.; Dutton, J.E.; Frost, P. The contours and consequences of compassion at work. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prev. Treat. 2000, 3, 1a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Llorens, S. Flow at work: Evidence for an upward spiral of personal and organizational resources. J. Happiness Stud. 2006, 7, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1988; Volume 10, pp. 123–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.-W.; Ko, S.-H. How employees’ perceptions of CSR increase employee creativity: Mediating mechanisms of compassion at work and intrinsic motivation. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worline, M.C.; Dutton, J.E. Awakening Compassion at Work: The Quiet Power That Elevates People and Organizations; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.; Frost, P.; Worline, M.; Lilius, J.; Kanov, J. Leading in times of trauma. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dutton, J.E. Energize Your Workplace: How to Create and Sustain High-Quality Connections at Work; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, P. Toxic Emotions at Work: How Compassionate Managers Handle Pain and Conflict; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, W.A. Caring for the caregivers: Patterns of organizational caregiving. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 539–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-H.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y. Compassion and workplace incivility: Implications for open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.C. Impact of providing compassion on job performance and mental health: The moderating effect of interpersonal relationship quality. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2017, 49, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Arya, B.; Farooqi, S. Workplace behavioral antecedents of job performance: Mediating role of thriving. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 755–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.; Rhee, S.-Y. Exploring the relationships between compassion at work, the evaluative perspective of positive work-related identity, service employee creativity, and job performance. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.-W.; Hur, W.-M.; Ko, S.-H.; Kim, J.-W.; Yoo, D.-K. Positive work-related identity as a mediator of the relationship between compassion at work and employee outcomes. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2016, 26, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.C. Mediating positive moods: The impact of experiencing compassion at work. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-H.; Choi, Y. Compassion and job performance: Dual-paths through positive work-related identity, collective self esteem, and positive psychological capital. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, P.J.; Dutton, J.E.; Maitlis, S.; Lilius, J.M.; Kanov, J.M.; Worline, M.C. Seeing organizations differently: Three lenses on compassion. In The SAGE Handbook of Organization Studies; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 843–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, M.J. Proactive behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Crant, J.M.; Kraimer, M.L. Proactive personality and career success. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, S.J.; Black, J.S. Proactivity during organizational entry: The role of desire for control. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, D.A.; Kozlowski, S.W. Newcomer information seeking: Individual and contextual influences. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 1997, 5, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.D.; Jablin, F.M. Information seeking during organizational entry: Influences, tactics, and a model of the process. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 92–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C.; Kozlowski, S.W. Organizational socialization as a learning process: The role of information acquisition. Pers. Psychol. 1992, 45, 849–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D. Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.-Y.; Hur, W.-M.; Kim, M. The relationship of coworker incivility to job performance and the moderating role of self-efficacy and compassion at work: The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Approach. J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 32, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgärtner, M.K.; Böhm, S.A.; Dwertmann, D.J. Job performance of employees with disabilities: Interpersonal and intrapersonal resources matter. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2014, 34, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.; Catty, J.; Becker, T.; Drake, R.E.; Fioritti, A.; Knapp, M.; Lauber, C.; Rössler, W.; Tomov, T.; Van Busschbach, J. The effectiveness of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Job crafting and job performance: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 914–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, P.; Dutton, J.; Worline, M.; Wilson, A. Narratives of compassion in organizations. In Emotions in Organizations; Fineman, S., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kanov, J.; Maitlis, S.; Worline, M.; Dutton, J.; Frost, P.; Lilius, J. Compassion in organizational life. Am. Behav. Sci. 2004, 47, 808–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Spreitzer, G.M. Trust, connectivity, and thriving: Implications for innovative behaviors at work. J. Creat. Behav. 2009, 43, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboul-Ela, G.M.B.E. Reflections on workplace compassion and job performance. J. Hum. Values 2017, 23, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Wernsing, T.S.; Luthans, F. Can positive employees help positive organizational change? Impact of psychological capital and emotions on relevant attitudes and behaviors. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2008, 44, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Ashford, S.J. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Barrett, L.F.; Bartunek, J.M. The role of affective experience in work motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svejenova, S. The path with the heart: Creating the authentic career. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 947–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, H.P.; Totterdell, P.; Niven, K.; Barros, E. Leader affective presence and innovation in teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Cohn, M.A.; Coffey, K.A.; Pek, J.; Finkel, S.M. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacharkulksemsuk, T.; Fredrickson, B.L. Looking Back and glimpsing forward: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions as applied to organizations. Adv. Posit. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 1, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Losada, M.F. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, M. The role of work authenticity in linking strengths use to career satisfaction and proactive behavior: A two-wave study. Career Dev. Int. 2020, 25, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazazzara, A.; Tims, M.; De Gennaro, D. The process of reinventing a job: A meta–synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 116 Pt B, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Grant, A.M.; Johnson, V. When callings are calling: Crafting work and leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 973–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Tims, M.; Derks, D. Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M.; Choi, W.H. Coworker support as a double-edged sword: A moderated mediation model of job crafting, work engagement, and job performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1417–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. The exit of social mobility and the voice of social change: Notes on the social psychology of intergroup relations. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1975, 14, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Ilies, R. Charisma, positive emotions and mood contagion. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W.; Phelps, C.C. Taking charge at work: Extrarole efforts to initiate workplace change. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroudi, S.E.; Khapova, S.N. The effects of age on job crafting: Exploring the motivations and behavior of younger and older employees in job crafting. In Leadership, Innovation and Entrepreneurship as Driving Forces of the Global Economy; Benlamri, R., Sparer, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D.T.A.M.; van Woerkom, M.; Wilkenloh, J.; Dorenbosch, L.; Denissen, J.J.A. Job crafting towards strengths and interests: The effects of a job crafting intervention on person–job fit and the role of age. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, T.E. Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 2005, 8, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.E.; Atinc, G.; Breaugh, J.A.; Carlson, K.D.; Edwards, J.R.; Spector, P.E. Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Brannick, M.T. Methodological urban legends: The misuse of statistical control variables. Organ. Res. Methods 2011, 14, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.J.; Hartman, N.; Cavazotte, F. Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 477–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, M. Reflection on success in promoting authenticity and proactive behavior: A two-wave study. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 41, 8793–8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoidbach, J.; Mikolajczak, M.; Gross, J.J. Positive interventions: An emotion regulation perspective. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 655–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Fulk, H.K.; Sarker, S. Building a compassionate workplace using information technology: Considerations for information systems research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldor, L. Public service sector: The compassionate workplace—The effect of compassion and stress on employee engagement, burnout, and performance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.I. Compassionate communication in the workplace: Exploring processes of noticing, connecting, and responding. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2007, 35, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehan, M. The compassionate workplace: Leading with the heart. Illn. Crisis Loss 2007, 15, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G.R.; Kern, M.L.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. Workplace well-being: The role of job crafting and autonomy support. Psychol. Well-Being 2015, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, S.K.; Klopper, H.C. Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nurs. Health Sci. 2010, 12, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabo, B.M. Compassion fatigue and nursing work: Can we accurately capture the consequences of caring work? Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2006, 12, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, E.A. Compassion fatigue in nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2010, 23, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M.C.; Baaten, S.M. How a learning-oriented organizational climate is linked to different proactive behaviors: The role of employee resilience. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 143, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Collins, C.G. Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.C.; Dolmans, D.; de Grave, W.; Sanabria, A.; Stassen, L.P. Job crafting to persist in surgical training: A qualitative study from the resident’s perspective. J. Surg. Res. 2019, 239, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbridge, R.; Ivanitskaya, L.; Spreitzer, G.; Boscart, V. Job crafting in registered nurses working in public health: A qualitative study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2022, 64, 151556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonocore, F.; de Gennaro, D.; Russo, M.; Salvatore, D. Cognitive job crafting: A possible response to increasing job insecurity and declining professional prestige. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 30, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, V.; Rousset, C.; Schäfer, B. Uncovering paradoxes of compassion at work: A dyadic study of compassionate leader behavior. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1112644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, K.; Al-Abbadey, M. Compassion fatigue and global compassion fatigue in practitioner psychologists: A qualitative study. Curr. Psychol. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Items | AVE | α | C.R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compassion | Com1 | 0.810 | 0.894 | 0.940 |

| Com2 | ||||

| Com3 | ||||

| Positive Emotion | PE1 | 0.813 | 0.916 | 0.947 |

| PE2 | ||||

| PE3 | ||||

| PE4 | ||||

| Job Crafting | JC1 | 0.786 | 0.808 | 0.864 |

| JC2 | ||||

| JC3 | ||||

| JC4 | ||||

| Job Performance | JP1 | 0.843 | 0.900 | 0.939 |

| JP2 | ||||

| JP3 | ||||

| JP4 | ||||

| JP5 |

| χ2 | df | p | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | NFI | IFI | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Model (M.M) | 141.270 | 95 | <0.001 | 1.487 | 0.040 | 0.985 | 0.957 | 0.985 | 0.981 |

| Controlled Model (C.M.) | 112.664 | 84 | <0.001 | 1.341 | 0.037 | 0.989 | 0.965 | 0.989 | 0.984 |

| Stepwise Analysis | Δχ2 | Δdf | Accepted Model | ||||||

| M.M.-C.M. | 28.606 | 11 | >0.05 | Measurement Model | |||||

| Construct | Items | λ | λ (CMV) | λ-λ (CMV) | SE | CR | AVE | α | C.R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compassion | Com1 | 0.853 | 0.725 | 0.128 | - | - | 0.810 | 0.894 | 0.940 |

| Com2 | 0.882 | 0.709 | 0.173 | 0.057 | 18.599 | ||||

| Com3 | 0.843 | 0.743 | 0.100 | 0.057 | 17.750 | ||||

| Positive Emotion | PE1 | 0.831 | 0.800 | 0.031 | - | - | 0.813 | 0.916 | 0.947 |

| PE2 | 0.788 | 0.747 | 0.041 | 0.046 | 20.412 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.871 | 0.814 | 0.057 | 0.058 | 17.997 | ||||

| PE4 | 0.881 | 0.792 | 0.089 | 0.062 | 18.182 | ||||

| Job Crafting | JC1 | 0.794 | 0.711 | 0.083 | - | - | 0.786 | 0.808 | 0.864 |

| JC2 | 0.685 | 0.661 | 0.024 | 0.081 | 11.291 | ||||

| JC3 | 0.741 | 0.679 | 0.062 | 0.076 | 12.326 | ||||

| JC4 | 0.564 | 0.443 | 0.121 | 0.083 | 9.429 | ||||

| Job Performance | JP1 | 0.830 | 0.739 | 0.091 | - | - | 0.843 | 0.900 | 0.939 |

| JP2 | 0.805 | 0.719 | 0.086 | 0.051 | 19.712 | ||||

| JP3 | 0.803 | 0.697 | 0.106 | 0.060 | 15.920 | ||||

| JP4 | 0.813 | 0.756 | 0.057 | 0.060 | 16.203 | ||||

| JP5 | 0.726 | 0.627 | 0.099 | 0.065 | 13.960 | ||||

| χ2 = 112.664 (df = 79, p = 0.000), CFI = 0.989, TLI = 0.984, IFI = 0.989, NFI = 0.965, RMSEA = 0.037, RMR = 0.015 | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Compassion | 3.433 | 0.706 | 0.810 | |||

| 2. Positive Emotion | 3.229 | 0.707 | 0.356 ** | 0.813 | ||

| 3. Job Crafting | 3.356 | 0.667 | 0.350 ** | 0.301 ** | 0.786 | |

| 4. Job Performance | 3.682 | 0.654 | 0.361 ** | 0.289 ** | 0.658 ** | 0.843 |

| Hypotheses | Path | β | SE | CR | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | Compassion ⟶ Job Performance | 0.121 | 0.041 | 2.921 | <0.01 |

| Hypothesis 2 | Compassion ⟶ Positive Emotion | 0.337 | 0.053 | 6.329 | <0.001 |

| Hypothesis 3 | Positive Emotion ⟶ Job Crafting | 0.262 | 0.052 | 5.085 | <0.001 |

| Hypothesis 4 | Job Crafting ⟶ Job Performance | 0.581 | 0.043 | 13.511 | <0.001 |

| From ⟶ To | Indirect Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | CIlow | CIhigh | |

| Total indirect effect | 0.202 | 0.117 | 0.286 |

| Comp ⟶ PE ⟶ JP | 0.020 | 0.014 | 0.056 |

| Comp ⟶ JC ⟶ JP | 0.148 | 0.075 | 0.221 |

| Comp ⟶ PE ⟶ JC ⟶ JP | 0.034 | 0.008 | 0.068 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, Y.; Ko, S.-H. Compassion Catalysts: Unveiling Proactive Pathways to Job Performance. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010057

Choi Y, Ko S-H. Compassion Catalysts: Unveiling Proactive Pathways to Job Performance. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Yongjun, and Sung-Hoon Ko. 2024. "Compassion Catalysts: Unveiling Proactive Pathways to Job Performance" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010057

APA StyleChoi, Y., & Ko, S.-H. (2024). Compassion Catalysts: Unveiling Proactive Pathways to Job Performance. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010057