Intra- and Inter-Individual Associations of Family-to-Work Conflict, Psychological Distress, and Job Satisfaction: Gender Differences in Dual-Earner Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

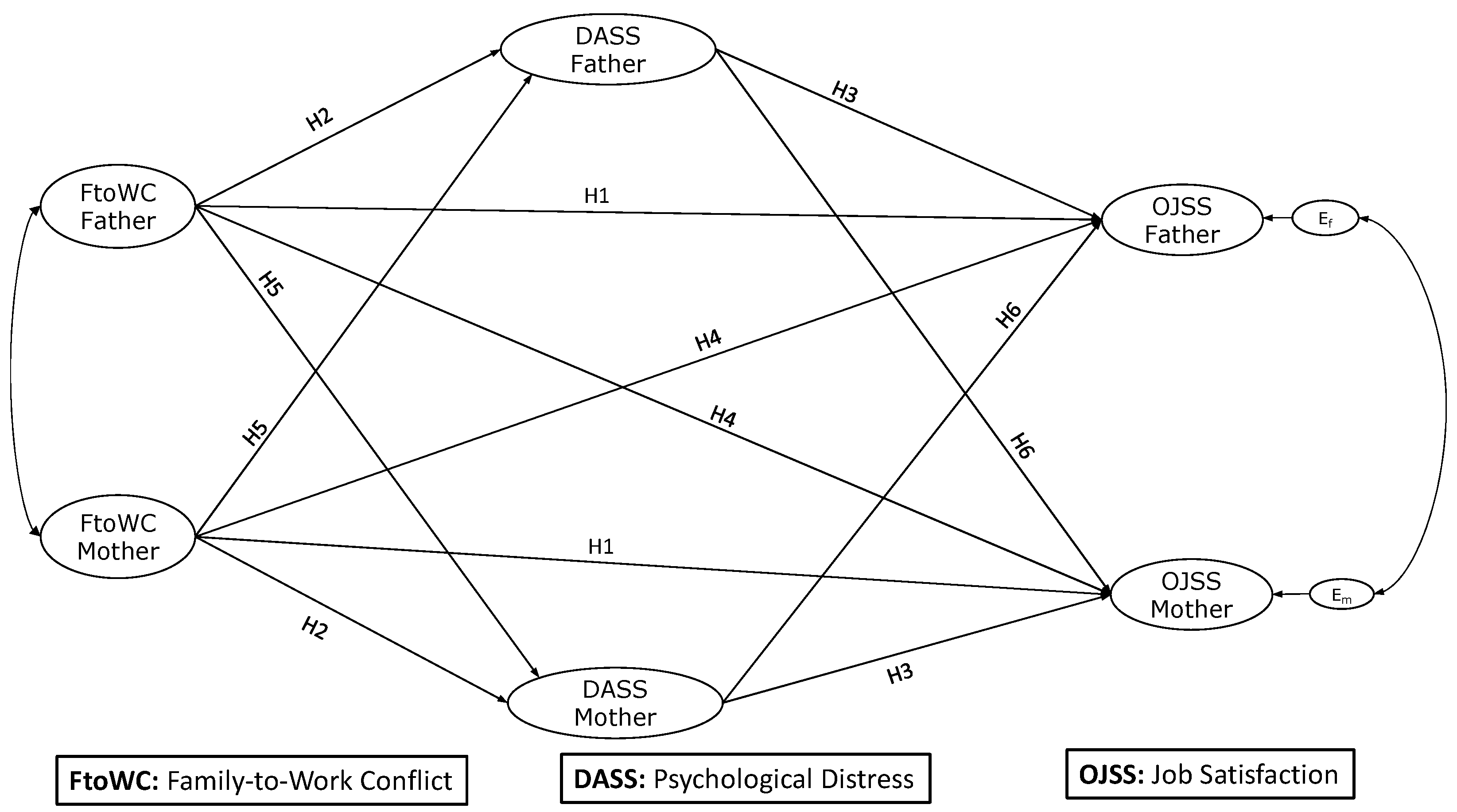

Theoretical and Empirical Frameworks and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

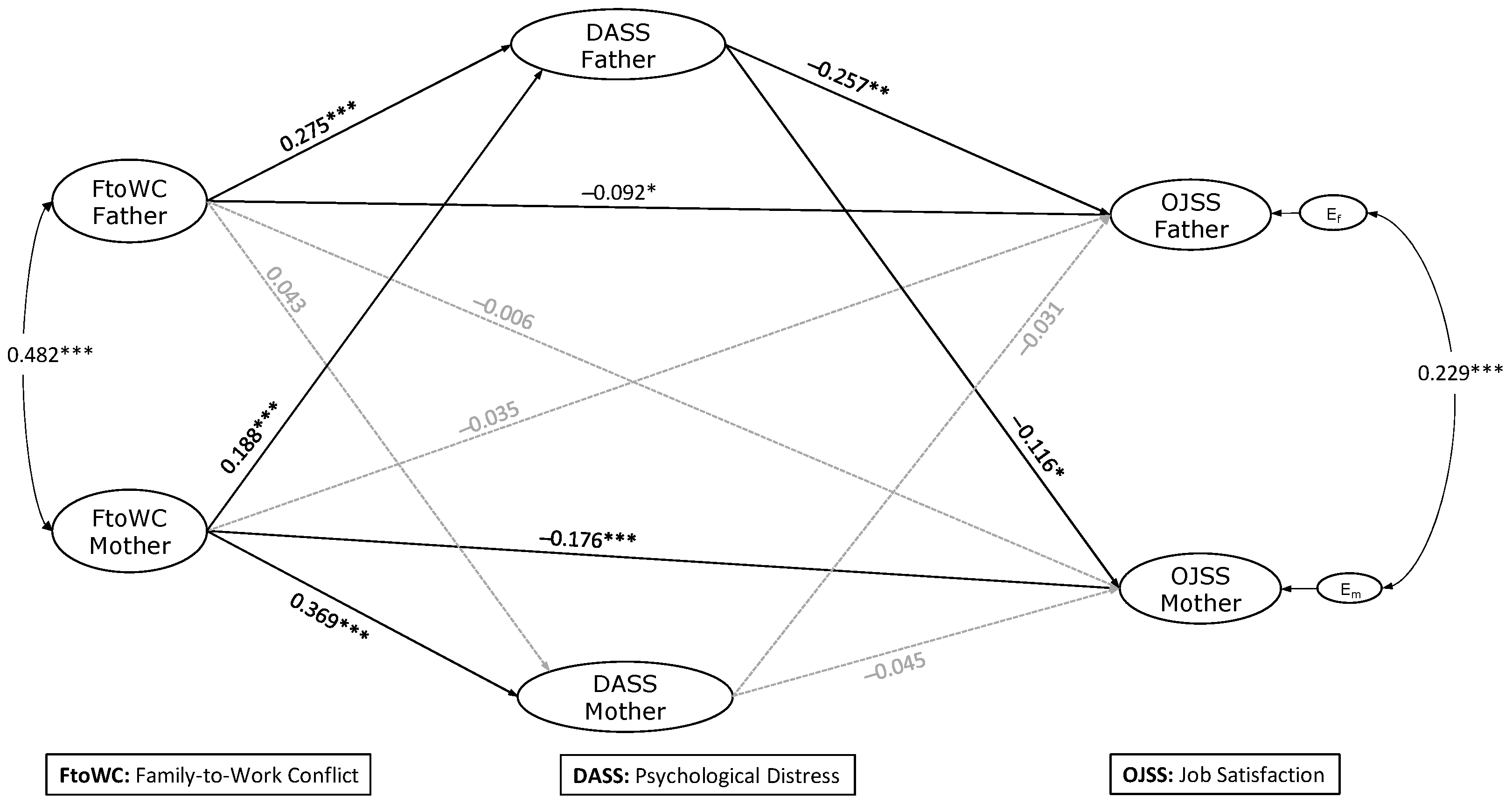

3.2. APIM Results: Testing Actor-Partner Hypotheses

3.3. Testing the Mediating Role of Psychological Distress

4. Discussion

4.1. Actor Effects

4.2. Partner Effects

4.3. The Mediating Role of Psychological Distress

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Estimate | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Family socioeconomic status→ Mothers’ DASS. | −0.101 | 0.012 * |

| Number of children → Mothers’ DASS. | 0.027 | 0.476 |

| Mother’s age → Mothers’ DASS. | 0.023 | 0.649 |

| Father’s age → Mothers’ DASS. | −0.045 | 0.358 |

| Mothers’ working hours → Mothers’ DASS. | −0.071 | 0.080 |

| Fathers’ working hours → Mothers’ DASS. | 0.033 | 0.389 |

| Mothers’ type of employment → Mothers’ DASS. | 0.027 | 0.498 |

| Fathers’ type of employment → Mothers’ DASS. | −0.027 | 0.480 |

| City of residence → Mothers’ DASS. | 0.028 | 0.492 |

| Family socioeconomic status→ Fathers’ DASS. | 0.026 | 0.553 |

| Number of children → Fathers’ DASS. | 0.034 | 0.401 |

| Mother’s age → Fathers’ DASS. | 0.050 | 0.396 |

| Father’s age → Fathers’ DASS. | 0.012 | 0.831 |

| Mothers’ working hours → Fathers’ DASS. | −0.058 | 0.175 |

| Fathers’ working hours → Fathers’ DASS. | −0.003 | 0.949 |

| Mothers’ type of employment → Fathers’ DASS. | −0.037 | 0.383 |

| Fathers’ type of employment → Fathers’ DASS. | 0.004 | 0.924 |

| City of residence → Fathers’ DASS. | 0.025 | 0.510 |

| Family socioeconomic status→ Mothers’ OJSS. | 0.105 | 0.005 ** |

| Number of children → Mothers’ OJSS. | 0.003 | 0.923 |

| Mothers’ age → Mothers’ OJSS. | 0.191 | 0.001 ** |

| Fathers’ age → Mothers’ OJSS. | −0.019 | 0.733 |

| Mothers’ working hours → Mothers’ OJSS. | −0.027 | 0.481 |

| Fathers’ working hours → Mothers’ OJSS. | 0.006 | 0.864 |

| Mothers’ type of employment → Mothers’ OJSS. | 0.081 | 0.032 * |

| Fathers’ type of employment → Mothers’ OJSS. | 0.045 | 0.219 |

| City of residence → Mothers’ OJSS. | 0.030 | 0.499 |

| Family socioeconomic status→ Fathers’ OJSS. | 0.049 | 0.183 |

| Number of children → Fathers’ OJSS. | −0.005 | 0.875 |

| Mothers’ age → Fathers’ OJSS. | 0.052 | 0.249 |

| Fathers’ age → Fathers’ OJSS. | 0.091 | 0.047 * |

| Mothers’ working hours → Fathers’ OJSS. | −0.076 | 0.055 |

| Fathers’ working hours → Fathers’ OJSS. | −0.014 | 0.699 |

| Mothers’ type of employment → Fathers’ OJSS. | 0.039 | 0.302 |

| Fathers’ type of employment → Fathers’ OJSS. | 0.051 | 0.157 |

| City of residence → Fathers’ OJSS. | 0.022 | 0.442 |

References

- De Aráujo, V.; Ribeiro, M.T.; Carvalho, V.S. The work-family interface and COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 914474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, S.; Brugnera, A.; Adorni, R.; Molgora, S.; Reverberi, E.; Manzi, C.; Angeli, M.; Bagirova, A.; Benet-Martinez, V.; Camilleri, L.; et al. Workers’ individual and dyadic coping with the COVID-19 health emergency: A cross cultural study. J. Social. Personal. Relatsh. 2023, 40, 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, F.; Jiménez-Molina, Á. Psychological distress during the COVID-19 epidemic in Chile: The role of economic uncertainty. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Or, P.P.L.; Fang, Y.; Sun, F.; Poon, E.T.C.; Chan, C.K.M.; Chung, L.M.Y. From parental issues of job and finance to child well-being and maltreatment: A systematic review of the pandemic-related spillover effect. Child. Abus. Negl. 2023, 137, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B. A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, A.A.; Breitenecker, R.J.; Shah, S.A.M. Relation of work-life balance, work-family conflict, and family-work conflict with the employee performance-moderating role of job satisfaction. South. Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2018, 7, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Sykes, T.A.; Chan, F.K.Y.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Hu, P.J.H. Children’s Internet addiction, family-to-work conflict, and job outcomes: A study of parent-child dyads. MIS Q. 2019, 43, 903–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phungsoonthorn, T.; Charoensukmongkol, P. How does mindfulness help university employees cope with emotional ex-haustion during the COVID-19 crisis? The mediating role of psychological hardiness and the moderating effect of workload. Scand. J. Psychol. 2022, 63, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, M.; Peters, E.; Diewald, M. COVID-19 and work–family conflicts in Germany: Risks and chances across gender and parenthood. Front. Sociol. 2022, 6, 780740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Wu, X.; Ren, Y.; Wang, X. Actor-partner association of work–family conflict and parental depressive symptoms during COVID-19 in China: Does coparenting matter? Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2022, 14, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandya, B.; Patterson, L.; Cho, B. Pedagogical transitions experienced by higher education faculty members—“Pre-Covid to Covid”. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2022, 14, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Jiang, M. “Ideal employees” and “good wives and mothers”: Influence mechanism of bi-directional work–family conflict on job satisfaction of female university teachers in China. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1166509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M. Stress and strain crossover. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 717–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasharudin, N.A.M.; Idris, M.A.; Young, L.M. The effects of work conditions on burnout and depression among Malaysian spouses: A crossover explanation. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 30, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, L.; Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Saracostti, M.; Poblete, H.; Lobos, G.; Adasme-Berríos, C.; Lapo, M.; Concha-Salgado, A. Job satisfaction as a mediator between family-to-work conflict and satisfaction with family life: A dyadic analysis in dual-earner parents. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 491–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, L.; García, R.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Schnettler, B. Effects of work-to-family enrichment on psychological distress and family satisfaction: A dyadic analysis in dual-earner parents. Scand. J. Psychol. 2022, 63, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Concha-Salgado, A.; Orellana, L.; Saracostti, M.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Poblete, H.; Lobos, G.; Adasme-Berríos, C.; Lapo, M.; Beroíza, K.; et al. Revisiting the link between domain satisfaction and life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: Job-related moderators in triadic analysis in dual-earner parents with adolescent children. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1108336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Moya, G.; Carvacho, H.; Álvarez, B. Azul y rosado: La (aún presente) trampa de los estereotipos de género. MIDevi-Dencias 2020, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- López-Contreras, N.; López-Jiménez, T.; Horna-Campos, O.; Mazzei, M.; Anigstein, M.; Jacques-Aviñó, C. Impacto del con-finamiento por la COVID-19 en la salud autopercibida en Chile según género. Gac. Sanit. 2022, 36, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barría-Sandoval, C.; Ferreira, G.; Lagos, B.; Montecino, C. Assessing the effectiveness of quarantine measures during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile using Bayesian structural time series models. Infect. Dis. Model. 2022, 4, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobierno de Chile. Plan Paso a Paso. July 2020. Available online: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/ConocePlanPasoaPaso.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Ministerio de Hacienda; Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo. Cuarto Reporte de Indicadores de Género en las Em-Presas en Chile. 2022. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/original-cuarto-reporte-indicadores-genero-2022-digital.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Wang, C.; Cheong, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Havewala, M.; Ye, Y. Parent work–life conflict and adolescent adjustment during COVID-19: Mental health and parenting as mediators. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Kreiner, G.E.; Fugate, M. All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; Kashy, D.A.; Cook, W.L. Dyadic Data Analysis, 1st ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, R.L.; Kenny, D.A.; Ledermann, T. Moderation in the actor–partner interdependence model. Pers. Relatsh. 2015, 22, 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattusamy, M.; Jacob, J. The mediating role of family-to-work conflict and work-family balance in the relationship between family support and family satisfaction: A three path mediation approach. Curr. Psychol. 2017, 36, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hite, L.M.; McDonald, K.S. Careers after COVID-19: Challenges and changes. Human. Resour. Dev. Int. 2020, 23, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, M.D.; Vallellano, M.D.; Oliver, C.; Mateo, I. What makes one feel eustress or distress in quarantine? An analysis from conservation of resources (COR) theory. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthatorn, P.; Charoensukmongkol, P. Effects of trust in organizations and trait mindfulness on optimism and perceived stress of flight attendants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pers. Rev. 2023, 52, 882–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agho, A.O.; Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W. Discriminant validity of measures of job satisfaction, positive affectivity and negative affectivity. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1992, 65, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D.; Latshaw, B.A. Spillover and crossover effects of work-family conflict among married and cohabiting couples. Soc. Ment. Health 2020, 10, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alawi, A.; Al-Saffar, E.; Alomohammedsaleh, Z.; Alotaibi, H.; Al-Alawi, E. A study of the effects of work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and work-life balance on Saudi female teachers’ performance in the public education sector with job satisfaction as a moderator. J. Int. Womens Stud. 2021, 22, 486–503. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T.D.; French, K.A.; Dumani, S.; Shockley, K.M. A cross-national meta-analytic examination of predictors and outcomes associated with work–family conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 539–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagger, J.; Li, A. Being important matters: The impact of work and family centralities on the family-to-work conflict–satisfaction relationship. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 473–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Contreras, F.; Fernández, I.A. Work–family and family–work conflict and stress in times of COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 951149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, M. Dual stressors and female pre-school teachers & job satisfaction during the COVID-19: The mediation of work-family conflict. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 691498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, A.; Vázquez, J. Las barreras del desarrollo laboral de las mujeres. Una aproximación latinoamericana. América Crítica 2020, 4, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Lyu, X.; Pan, L.; Chen, A. The role conflict-burnout-depression link among Chinese female health care and social service providers: The moderating effect of marriage and motherhood. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D.; Fan, W. Workplace flexibility, work–family interface, and psychological distress: Differences by family caregiving obligations and gender. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 1825–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro, P.; Saracostti, M.; Kinkead, A.; Grau, M.O. Niñez y adultez. Diálogos frente a tensiones familiares, laborales y del cuidado. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Ninez Juv. 2017, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Da, S.; Guo, H.; Zhang, X. Work–family conflict and mental health among female employees: A sequential mediation model via negative affect and perceived stress. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muafiah, E.; Sofiana, N.E.; Nurhidayati, M. Exploring the Influence of Work-Family Balance and Burnout on Working Mothers' Character-Building Efforts in a Post-Pandemic World. Islam. Guid. Couns. J. 2023, 6, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghawadra, S.F.; Abdullah, K.L.; Choo, W.Y.; Phang, C.K. Psychological distress and its association with job satisfaction among nurses in a teaching hospital. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 4087–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, A.A.; Seidler, Z.E.; Oliffe, J.L.; Rice, S.M.; Kealy, D.; Walther, A.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S. Job satisfaction and psychological distress among help-seeking men: Does meaning in life play a role? Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Cropanzano, R.; Butler, A.; Shao, P.; Westman, M. Work–family crossover: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2021, 28, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D.; Borgmann, L.S. Work–family conflict and depressive symptoms among dual-earner couples in Germany: A dyadic and longitudinal analysis. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 104, 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Lapo, M.; Hueche, C. Depression and satisfaction in different domains of life in dual-earner families: A dyadic analysis. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2019, 51, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, P.; Du, H.; King, R.B.; Zhou, N.; Cao, H.; Lin, X. Well-being contagion in the family: Transmission of happiness and distress between parents and children. Child. Indic. Res. 2019, 12, 2189–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. Longitudinal dyadic associations between depressive symptoms and life satisfaction among Chinese married couples and the moderating effect of within-dyad age discrepancy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Haar, J.M.; van der Lippe, T. Crossover of distress due to work and family demands in dual-earner couples: A dyadic analysis. Work Stress 2010, 24, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanine, K.K.; Eddleston, K.A.; Combs, J.G. Same boundary management preference, different outcome: Toward a gendered perspective of boundary theory among entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.; Sama, M.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. How Human Resource Management Practices Translate Into Sustainable Organizational Performance: The Mediating Role Of Product, Process And Knowledge Innovation. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 1, 1009–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arredondo, F.G.; Vázquez, J.C.; Velázquez, L.M. STEM and Gender Gap in Latin America. Rev. Col. San. Luis 2019, 9, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Boletín Estadístico: Empleo Trimestral (Report n°265, 27 November 2020). Available online: https://bit.ly/3uj72Yk (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Norma Chilena NCh3262:2021: Gestión de Igualdad de Género y Conciliación de la Vida Laboral, Familiar y Personal. Available online: https://www.sernameg.gob.cl/?page_id=32792 (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Global Gender Gap Report 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/45eiQZN (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD). Principales Resultados de la Primera Medición del Bienestar Social en Chile. 2021. Available online: https://www.estudiospnud.cl/informes-desarrollo/principales-resultados-de-la-primera-medicion-del-bienestar-social-en-chile/ (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T.; Geurts, S.; Pulkkinen, L. Types of work-family interface: Well-being correlates of negative and positive spillover between work and family. Scand. J. Psychol. 2006, 47, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, P.; Lovibond, S. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, A.; Wong, J.; Bagge, C.; Freedenthal, S.; Gutierrez, P.; Lozano, G. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21): Further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 68, 1322–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cómo Clasificar los Grupos Socioeconómicos en Chile. Available online: http://bit.ly/47zgsyh (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Ledermann, T.; Rudaz, M.; Grob, A. Analysis of group composition in multimember multigroup data. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 24, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struc. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, R.S.; Cheung, G.W. Estimating and comparing specific mediation effects in complex latent variable models. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 15, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Schieman, S. What happens at home does not stay at home: Family-to-work conflict and the link between relationship strains and quality. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2023, 44, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gan, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, F.; Liu, J.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Job satisfaction and its associated factors among general practitioners in China. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 2020, 33, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazaki, T.; Yamauchi, T.; Takenaka, K.; Suka, M. The link between involuntary non-regular employment and poor mental health: A cross-sectional study of Japanese workers. Int. J. Psychol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrow, S.R.; Ganzach, Y.; Liu, Y. Time and job satisfaction: A longitudinal study of the differential roles of age and tenure. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2558–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicijevic, N.; Paunović, K.I. Employee and the self-employed job satisfaction: Similarities and differences. Manag. J. Sustain. Bus. Manag. Solut. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 24, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlíková, M.; Maturkanič, P.; Akimjak, A.; Mazur, S.; Timor, T. Social Interventions in the Family in the Post-COVID Pandemic Period. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2023, 14, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmano, C.G.; Manuti, A.; Girardi, S.; Balenzano, C. From Conflict to Balance: Challenges for Dual-Earner Families Man-aging Technostress and Work Exhaustion in the Post-Pandemic Scenario. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Araoz, E.G.; Bautista Quispe, J.A.; Velazco Reyes, B.; Mamani Coaquira, H.; Ascona Garcia, P.P.; Arias Palomino, Y.L. Post-Pandemic Mental Health: Psychological Distress and Burnout Syndrome in Regular Basic Education Teachers. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, T.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, L.; Guo, S.; Li, H.; Sun, Q. Primary care provider's job satisfaction and organiza-tional commitment after COVID-19 restrictions ended: A mixed-method study using a mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 873770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Araoz, E.G.; Gallegos-Ramos, N.A.; Paredes-Valverde, Y.; Quispe-Herrera, R.; Mori-Bazán, J. Workload and Burnout syndrome as predictors of job satisfaction in Peruvian teachers. Univ. Soc. 2023, 15, 575–582. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Temuco (n = 430) | Rancagua (n = 430) | Total Sample | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [Mean (SD)] a | ||||

| Father | 42.0 (8.6) | 42.3 (7.8) | 42.2 (8.2) | 0.607 |

| Mother | 38.6 (7.3) | 39.4 (6.6) | 39.0 (6.9) | 0.091 |

| Number of family members [Mean (SD)] a | 4.3 (1.1) | 4.3 (1.0) | 4.3 (1.0) | 0.921 |

| Number of children [Mean (SD)] a | 2.2 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.9) | 0.525 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) (%) b | ||||

| High | 1.6 | 3.7 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Middle | 74.9 | 83.0 | 79.0 | |

| Low | 23.5 | 13.3 | 18.4 | |

| Mothers’ type of employment (%) b | ||||

| Employee | 68.1 | 62.8 | 65.5 | 0.099 |

| Self-employed | 31.9 | 37.2 | 34.5 | |

| Fathers’ type of employment (%) b | ||||

| Employee | 73.5 | 75.3 | 74.4 | 0.532 |

| Self-employed | 26.5 | 24.7 | 25.6 | |

| Mothers’ working hours (%) b | ||||

| 45 h per week | 48.4 | 44.0 | 46.2 | 0.194 |

| Less than 45 h per week | 51.6 | 56.0 | 53.8 | |

| Fathers’ working hours (%) b | ||||

| 45 h per week | 69.8 | 67.2 | 68.5 | 0.419 |

| Less than 45 h per week | 30.2 | 32.8 | 30.2 |

| M (SD) | Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1. Mothers’ FtoWC | 7.22 (3.16) | 1 | 0.395 ** | 0.344 ** | 0.250 ** | −0.193 ** | −0.127 ** |

| 2. Fathers’ FtoWC | 6.44 (2.93) | 1 | 0.185 ** | 0.305 ** | −0.117 ** | −0.149 ** | |

| 3. Mothers’ DASS | 30.47 (10.43) | 1 | 0.376 ** | −0.145 ** | −0.139 ** | ||

| 4. Fathers’ DASS | 27.21 (8.44) | 1 | −0.144 ** | −0.226 ** | |||

| 5. Mothers’ OJSS | 22.30 (5.06) | 1 | 0.274 ** | ||||

| 6. Fathers’ OJSS | 22.10 (4.68) | 1 | |||||

| Specific Indirect Effects | Estimate | Lower 2.5% | Upper 2.5% | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers’ FtoWC → Fathers’ DASS → Fathers’ OJSS | −0.071 | −0.091 | −0.031 | <0.001 *** |

| Mothers’ FtoWC → Mothers’ DASS → Mothers’ OJSS | −0.017 | −0.047 | 0.014 | 0.298 |

| Mothers’ FtoWC → Fathers’ DASS → Mothers’ OJSS | −0.032 | −0.041 | −0.002 | 0.032 * |

| Fathers’ FtoWC → Mothers’ DASS → Fathers’ OJSS | −0.001 | −0.005 | 0.003 | 0.574 |

| Mothers’ FtoWC → Fathers’ DASS → Fathers’ OJSS | −0.048 | −0.075 | −0.018 | 0.001 ** |

| Mothers’ FtoWC → Mothers’ DASS → Fathers’ OJSS | −0.011 | −0.041 | 0.019 | 0.477 |

| Fathers’ FtoWC → Fathers’ DASS → Mothers’ OJSS | −0.028 | −0.054 | −0.002 | 0.037 * |

| Fathers’ FtoWC → Mothers’ DASS → Mothers’ OJSS | −0.002 | −0.006 | 0.003 | 0.442 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Orellana, L.; Saracostti, M.; Poblete, H.; Lobos, G.; Adasme-Berríos, C.; Lapo, M.; Beroiza, K.; Concha-Salgado, A.; et al. Intra- and Inter-Individual Associations of Family-to-Work Conflict, Psychological Distress, and Job Satisfaction: Gender Differences in Dual-Earner Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010056

Schnettler B, Miranda-Zapata E, Orellana L, Saracostti M, Poblete H, Lobos G, Adasme-Berríos C, Lapo M, Beroiza K, Concha-Salgado A, et al. Intra- and Inter-Individual Associations of Family-to-Work Conflict, Psychological Distress, and Job Satisfaction: Gender Differences in Dual-Earner Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchnettler, Berta, Edgardo Miranda-Zapata, Ligia Orellana, Mahia Saracostti, Héctor Poblete, Germán Lobos, Cristian Adasme-Berríos, María Lapo, Katherine Beroiza, Andrés Concha-Salgado, and et al. 2024. "Intra- and Inter-Individual Associations of Family-to-Work Conflict, Psychological Distress, and Job Satisfaction: Gender Differences in Dual-Earner Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010056

APA StyleSchnettler, B., Miranda-Zapata, E., Orellana, L., Saracostti, M., Poblete, H., Lobos, G., Adasme-Berríos, C., Lapo, M., Beroiza, K., Concha-Salgado, A., Riquelme-Segura, L., Sepúlveda, J. A., & Reutter, K. (2024). Intra- and Inter-Individual Associations of Family-to-Work Conflict, Psychological Distress, and Job Satisfaction: Gender Differences in Dual-Earner Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010056