How Information Framing Nudges Acceptance of China’s Delayed Retirement Policy: A Moderated Mediation Model of Anchoring Effects and Perceived Fairness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Policy Acceptance

- Perceptions of policies and their attributes, such as benefits, costs, effectiveness, and fairness [10]. The perceived fairness of a policy emerges as a paramount influence of its acceptance [10,13,14,15,16]. A thematic analysis was conducted by scholars on over 60 policy articles related to environmental taxes, and it was found that people are more likely to support environmental policies when they perceive the policy to be fair in terms of cost distribution and social sharing [17].

- Contextual factors of policy acceptance, such as media exposure [18,19] and information framing [20]. Research from Sweden indicated higher public acceptance of a carbon tax policy following the release of the documentary “An Inconvenient Truth” and the publication of “Stern Review” [21]. During the COVID-19 crisis, positive media framing of expert predictions on GDP growth bolstered support for pandemic policies, especially among those expecting an economic downturn [22]. This accentuates the pivotal role of information framing in shaping public opinion and supporting government policies.

2.2. Attribute Framing Effect and Its Impact on Persuasion

2.3. The Impact of Perceived Fairness on Policy Acceptance and the Framing Effect

2.4. The Anchoring Effect and Its Impact on Persuasion

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Research Overview

4. Study 1

4.1. Participants

4.2. Procedure and Measures

4.3. Result

4.3.1. Manipulation Check

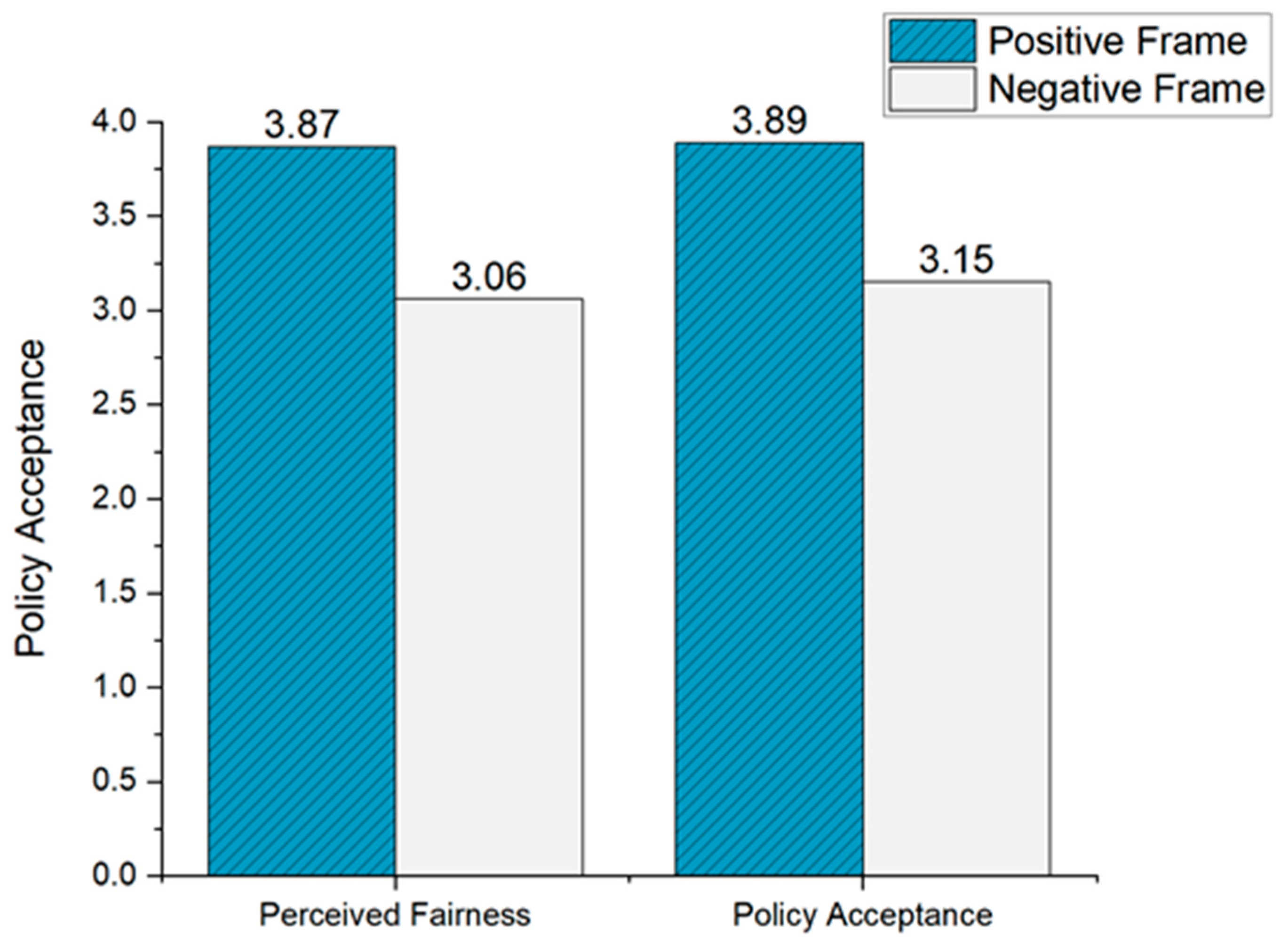

4.3.2. The Main Effect

5. Study 2

5.1. Participants

5.2. Procedure and Measures

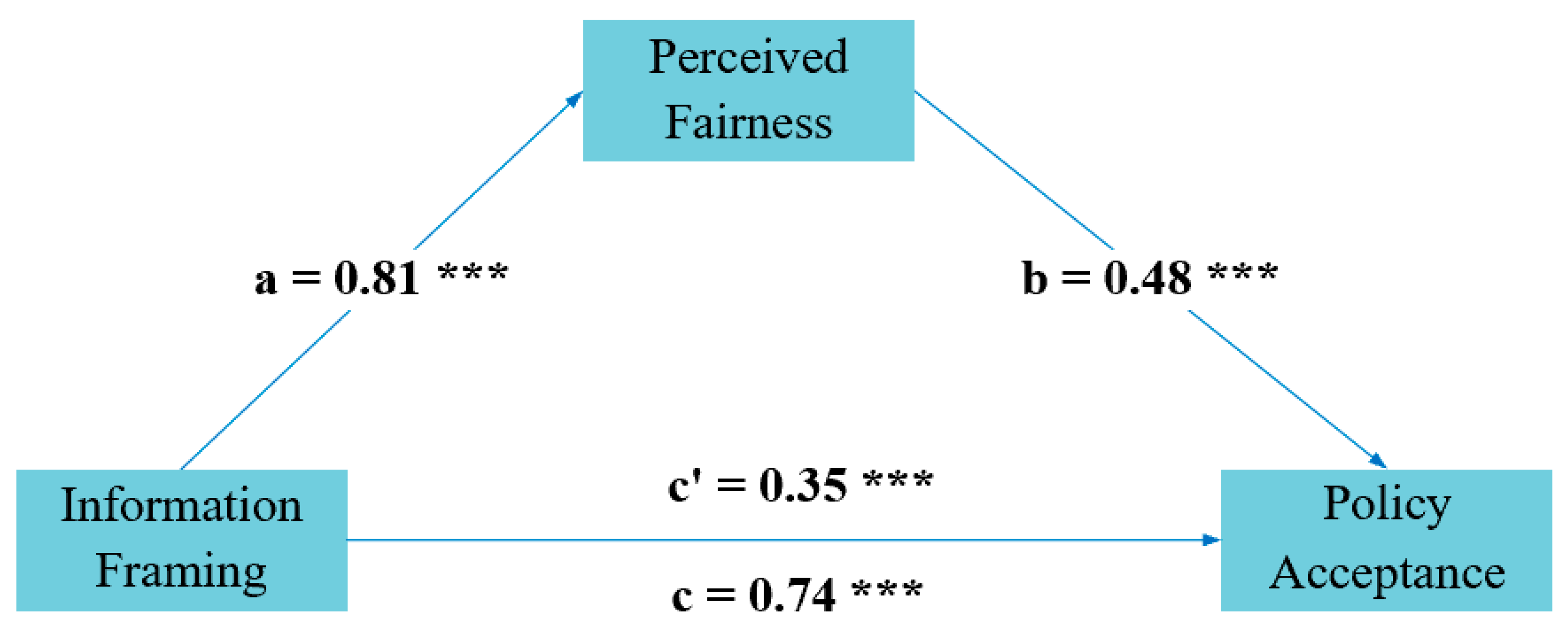

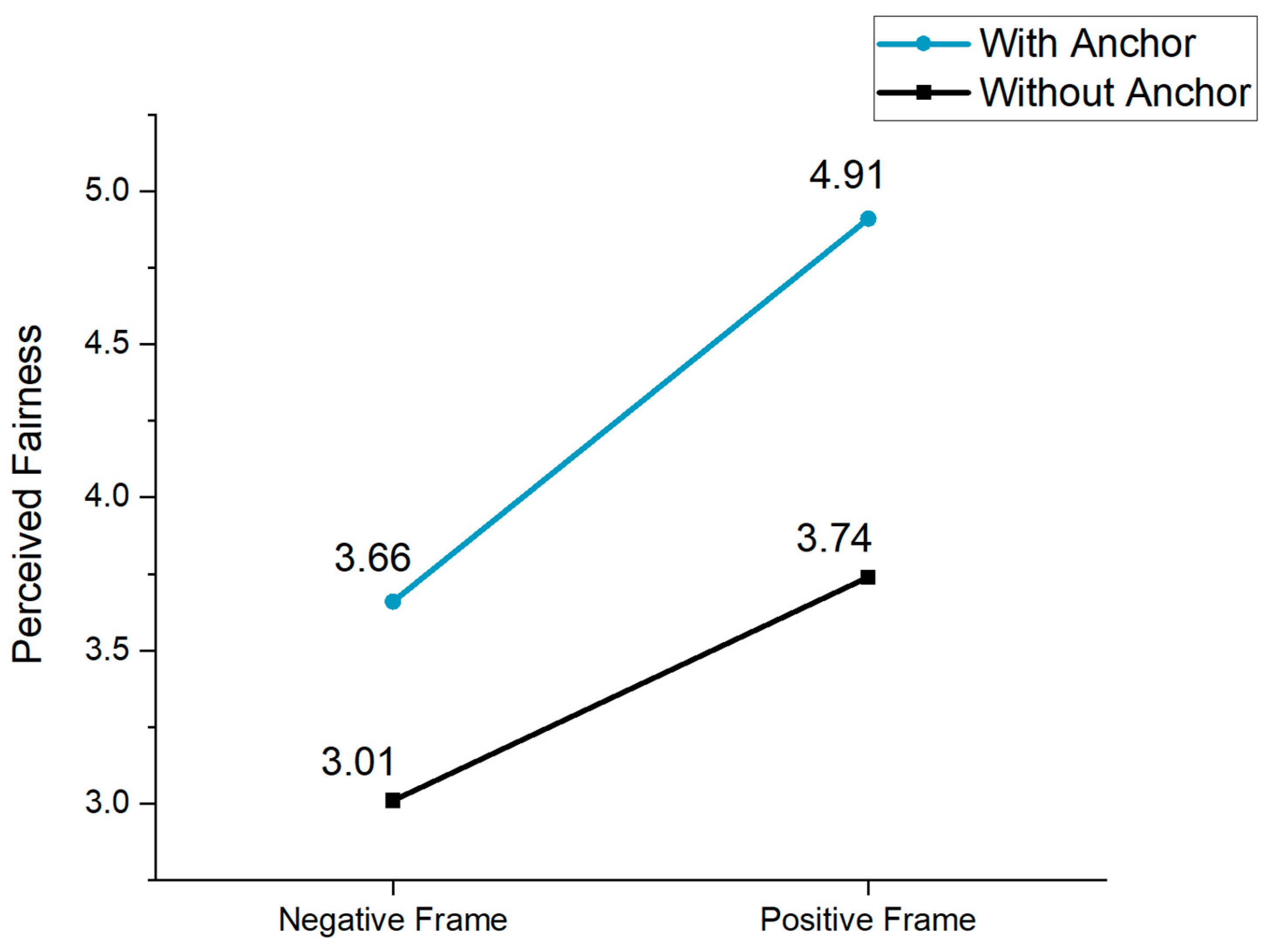

5.3. Result

5.3.1. Manipulation Check

5.3.2. The Main Effect

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Implications

7.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Groups | Scenario | Material Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The positive frame (fact presentation framing) | Currently, China’s statutory retirement age follows the standards set in 1951: 60 years old for men and 50 for female workers. However, the average starting age for China’s young workforce has been steadily delayed, with an average education duration extending to 13.7 years. The average life expectancy has also increased from around 40 years at the founding of New China to 78.2 years in 2021. Furthermore, adjusting the legal retirement age can alleviate the tax burden on young workers. Hence, in order to optimize policies based on actual social conditions, the Chinese government has proposed a “progressive delayed retirement policy”. During the retirement policy reform, differences among groups will be considered, individuals will be given more flexibility to choose early retirement, and the approach of delaying the retirement age by several months annually will be progressively implemented. |

| 2 | The negative frame (problem description framing) | Currently, China is confronted with numerous societal issues such as an aging population, pension fund deficits, and the diminishing demographic dividend. A recent report from the Chinese Academy of Sciences indicates that China’s pension fund will face expenditure exceeding income by 2028 and will run into a deficit by 2035. The prevailing legal retirement age in China is 60 for men and 50 for female workers. It is estimated that for every year the retirement age is delayed, the pension gap can be reduced by 20 billion yuan. Hence, to address the pension fund deficit and other related issues, the Chinese government has proposed a “progressive delayed retirement policy”. During the retirement policy reform, differences among groups will be considered, individuals will be given more flexibility to choose early retirement, and the approach of delaying the retirement age by several months annually will be progressively implemented. |

| Groups | Scenario | Material Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | With anchor (international perspective) | Since 2021, in the socialist country of Vietnam, the retirement age for men has been 60 years and 3 months, and for women, it has been 55 years and 4 months. Following this, every year the retirement age for men is delayed by 3 months, and for women by 4 months. By 2028, the retirement age in Vietnam will be 62 for men and 57 years and 8 months for women. |

| 2 | Without anchor (domestic perspective) | Since 2008, there have been calls in our country for the optimization of retirement policies. Only by 2021 was a clear proposal introduced to gradually delay the statutory retirement age. During the First Session of the 14th National People’s Congress in March 2023, Premier Li Keqiang stated in response to a journalist’s question that the delayed retirement policy would be rolled out at an appropriate time. |

References

- Cipriani, G.P.; Fioroni, T. Endogenous demographic change, retirement, and social security. Macroecon. Dyn. 2021, 25, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, H.; Achdut, L.; Youssim, I. Who Supports Delayed Retirement? A Study of Older Workers in Israel. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2009, 19, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, M.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y. Support strategies and platform construction for delayed retirement—Based on the perspective of “intelligent aging”. Soc. Sci. J. 2023, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.N.; Zhang, Z.R. Impact, Influencing Factors, and Guiding Policies of Implementing Delayed Retirement on Enterprise Organizations and Employees. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2023, 36, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R. Reward and Punishment Mechanism of Flexible Retirement Pension based on Inter-generational Equity. Fisc. Sci. 2022, 8, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Sanchez, C.; Schuitema, G.; Claudy, M.; Sancho-Esper, F. How Trust and Emotions Influence Policy Acceptance: The Case of the Irish Water Charges. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 57, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, W.G. Media Framing Effects on Public Vieho’wws of State Security: An Experiment of Economic Security Issue. J. Contemp. Asia-Pac. Stud. 2022, 31, 76–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.W.; Li, S. Exploring the Novel of Behavioral Public Management: Contents, Methods and Trends. Public Adm. Rev. 2018, 11, 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E. Doing the Right Thing Willingly Using the Insights of Behavioral Decision Research for Better Environmental Decisions. Behav. Found. Public Policy 2013, 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, S.; van den Bergh, J. What Explains Public Support for Climate Policies? A Review of Empirical and Experimental Studies. Clim. Policy 2015, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Leviston, Z.; Hurlstone, M.; Lawrence, C.; Walker, I. Emotions Predict Policy Support: Why It Matters How People Feel about Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 50, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Leiserowitz, A. The Role of Emotion in Global Warming Policy Support and Opposition. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grelle, S.; Hofmann, W. When and Why Do People Accept Public Policy Interventions? An Integrative Public Policy Acceptance Framework. Perspect. Psychol. Sci, 2023; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre-Andrés, S.; Drews, S.; van den Bergh, J. Perceived Fairness and Public Acceptability of Carbon Pricing: A Review of the Literature. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, S.; Walker, I. Acceptance and Support of the Australian Carbon Policy. Soc. Justice Res. 2013, 26, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; De Groot, J.I.M.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W.; Siero, F. General Antecedents of Personal Norms, Policy Acceptability, and Intentions: The Role of Values, Worldviews, and Environmental Concern. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 24, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.; Mohd Hasnu, N.N.; Ekins, P. Empirical Research of Public Acceptance on Environmental Tax: A Systematic Literature Review. Environments 2021, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Bennett, J. Household Perceptions of Climate Change and Preferences for Mitigation Action: The Case of the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme in Australia. Clim. Chang. 2011, 109, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Jiang, J.K.; Chen, H. The Effects of Different Means to Disseminate Information on Agricultural Policies and the Acceptanceby the Farmers. Issues Agric. Econ. 2005, 44, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, P.G.; Hornsey, M.J.; Bongiorno, R.; Jeffries, C. Promoting Pro-Environmental Action in Climate Change Deniers. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G. Why It Matters How We Frame the Environment. Environ. Commun. 2010, 4, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylong, P.; Koenings, F. Framing of Economic News and Policy Support during a Pandemic: Evidence from a Survey Experiment. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2023, 76, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. The Impact of the Financial–Economic Crisis on Sustainability Transitions: Financial Investment, Governance and Public Discourse. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2013, 6, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, B.I.; Shapiro, R.Y. Effects of Public Opinion on Policy. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1983, 77, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, I.P.; Schneider, S.L.; Gaeth, G.J. All Frames Are Not Created Equal: A Typology and Critical Analysis of Framing Effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1998, 76, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Crosta, A.; Marin, A.; Palumbo, R.; Ceccato, I.; La Malva, P.; Gatti, M.; Prete, G.; Palumbo, R.; Mammarella, N.; Di Domenico, A. Changing Decisions: The Interaction between Framing and Decoy Effects. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P. Message Framing and COVID-19 Vaccination Intention: Moderating Roles of Partisan Media Use and Pre-Attitudes about Vaccination. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 30686–30695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, M.; Mazzoni, D.; Pizzoli, S.F.M.; Gargenti, S.; Grasso, R.; Mazzocco, K.; Pravettoni, G. The Individuals’ Willingness to Get the Vaccine for COVID-19 during the Third Wave: A Study on Trust in Mainstream Information Sources, Attitudes and Framing Effect. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobayed, T.; Sanders, J.G. Moral Foundational Framing and Its Impact on Attitudes and Behaviours. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.M.; Tan, P. Research on the Application of Frame Effect and Its Application Techniques. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.C.; Xu, F.M.; Yu, H.H. The Psychological Mechanism and Influential Factors of Attribute Framing Effect. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 19, 1822–1833. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, E.; Zhou, J. Whose Policy Is It Anyway? Public Support for Clean Energy Policy Depends on the Message and the Messenger. Environ. Politics 2021, 31, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, M.; Nilsson Hed, A.; Harring, N.; Jagers, S. Meta-Analyses of Fifteen Determinants of Public Opinion about Climate Change Taxes and Laws. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, C.; van der Lans, I.; Van Rijnsoever, F.; Trijp, H. Consumer Acceptance of Population-Level Intervention Strategies for Healthy Food Choices: The Role of Perceived Effectiveness and Perceived Fairness. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7842–7862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, J. Bidding to Drive: Car License Auction Policy in Shanghai and Its Public Acceptance. Transp. Policy 2013, 27, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganegoda, D.B.; Folger, R. Framing Effects in Justice Perceptions: Prospect Theory and Counterfactuals. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2015, 126, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamliel, E.; Peer, E. Attribute Framing Affects the Perceived Fairness of Health Care Allocation Principles. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Y. Flexible Retirement, Incentive and Constraint, and the Internal Rate of Return of Social Pension Insurance. Insur. Stud. 2023, 30, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-S.; Cheng, F.-F. The Joint Effect of Framing and Anchoring on Internet Buyers’ Decision-Making. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2011, 10, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Boo, H.C. A Literature Review of the Anchoring Effect. J. Soc. Econ. 2011, 40, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Diao, H.; Wu, L. Influence of the Framing Effect, Anchoring Effect, and Knowledge on Consumers’ Attitude and Purchase Intention of Organic Food. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.C.; Zhang, E.Z.; Sun, W.W. The Impact of Random Discount Tactics on the Intention to Buy: Roles of Anchoring Effect and Price Fairness Perception. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- 2022 China Resident Retirement Readiness Index Survey Report; School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University and Aegon THTF Life Insurance: Beijing, China, 2022.

- James, O.; Jilke, S.R.; Van Ryzin, G.G. Experiments in Public Management Research: Challenges and Opportunities; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Ma, W.; Wu, J. Fostering Voluntary Compliance in the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analytical Framework of Information Disclosure. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 027507402094210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.; Rumrill, P. Pretest-Posttest Designs and Measurement of Change. Work 2003, 20, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.W.; Tan, X.H.; Liang, X.Y.; Zhu, Y.P. Nudging Fertility Policy: Two Survey Experiments of the Effect of Information Framework on Fertility Intention. Public Adm. Policy Rev. 2021, 10, 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.; Kim, H. Differential Effects of Message Framing on Obesity Policy Support Between Democrats and Republicans. Health Commun. 2016, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardisty, D.; Johnson, E.; Weber, E. A Dirty Word or a Dirty World? Attribute Framing, Political Affiliation, and Query Theory. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.J. Experimental Study on the Frame Effect of Urban Garbage Classification and Recycling Policy. Urban Probl. 2023, 42, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Stivers, C.; Pandey, S.; DeHart-Davis, L.; Hall, J.; Newcomer, K.; Portillo, S.; Sabharwal, M.; Strader, E.; Wright, J., II. Beyond Social Equity: Talking Social Justice in Public Administration. Public Adm. Rev. 2023, 83, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.C. Can “Learning from the Experience of Developed Countries” in Policy Advocacy Improve Public Policy Support? A Case Study of Property Tax Policy. J. Public Adm. 2022, 15, 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, B.; Loer, K.; Thomann, E. Beyond Nudge: Advancing the State-of-the-Art of Behavioural Public Policy and Administration. Policy Politics 2021, 49, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Levels | Study 1 (N = 225) | Study 2 (N = 383) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 125 | 55.6% | 199 | 52.0% |

| Female | 100 | 44.4% | 184 | 48.0% | |

| Age | 16–25 | 54 | 24.0% | 80 | 20.9% |

| 26–35 | 64 | 28.4% | 115 | 30.0% | |

| 36–45 | 46 | 20.4% | 86 | 22.5% | |

| 46–55 | 44 | 19.6% | 78 | 20.4% | |

| 56–65 | 17 | 7.6% | 24 | 6.3% | |

| Education level | Junior high School or below | 33 | 14.7% | 54 | 14.1% |

| High school/vocational secondary school | 52 | 23.1% | 76 | 19.8% | |

| Bachelor’s degree/ Associate degree | 113 | 50.2% | 199 | 52.0% | |

| Master’s degree or above | 27 | 12.0% | 54 | 14.1% | |

| Job position | Unemployed | 32 | 14.2% | 59 | 15.4% |

| Management | 65 | 28.9% | 127 | 33.2% | |

| Non-management | 128 | 56.9% | 197 | 51.4% | |

| Experimental Scenario | Policy Acceptance | M ± SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive frame (N = 112) | Pre-acceptance | 3.14 ± 2.04 | 8.20 | <0.001 |

| Post-acceptance | 3.89 ± 1.97 | |||

| Negative frame (N = 113) | Pre-acceptance | 3.15 ± 1.85 | 0.05 | 0.96 |

| Post-acceptance | 3.15 ± 1.72 |

| Acceptance) | B | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect of X on Y | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.53 |

| Indirect effect of X on Y | 0.39 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.59 |

| Total effect of X on Y | 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.98 |

| Perceived Fairness | Post-Acceptance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β(SE) | t | β(SE) | t | |

| Framing | 0.73 (0.17) *** | 4.22 | 0.31 (0.08) *** | 3.76 |

| Perceived fairness | 0.48 (0.03) *** | 16.06 | ||

| Anchoring | 0.66 (0.17) *** | 3.84 | ||

| Framing × anchoring | 0.55 (0.24) * | 2.24 | ||

| Pre-acceptance | 0.34 (0.03) *** | 10.98 | 0.62 (0.02) *** | 27.94 |

| R2 | 0.3958 | 0.8365 | ||

| F | 61.90 *** | 646.22 *** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, W.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y. How Information Framing Nudges Acceptance of China’s Delayed Retirement Policy: A Moderated Mediation Model of Anchoring Effects and Perceived Fairness. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010045

Zeng W, Zhao L, Zhao W, Zhang Y. How Information Framing Nudges Acceptance of China’s Delayed Retirement Policy: A Moderated Mediation Model of Anchoring Effects and Perceived Fairness. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Weixi, Lixia Zhao, Wenlong Zhao, and Yijing Zhang. 2024. "How Information Framing Nudges Acceptance of China’s Delayed Retirement Policy: A Moderated Mediation Model of Anchoring Effects and Perceived Fairness" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010045

APA StyleZeng, W., Zhao, L., Zhao, W., & Zhang, Y. (2024). How Information Framing Nudges Acceptance of China’s Delayed Retirement Policy: A Moderated Mediation Model of Anchoring Effects and Perceived Fairness. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010045