Self-Stigma and Mental Health in Divorced Single-Parent Women: Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Stigma and Mental Health

1.2. Self-Stigma and Self-Esteem

1.3. Self-Esteem and Mental Health

1.4. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Mental Health

2.2.2. Self-Stigma

2.2.3. Self-Esteem

2.2.4. Control Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Variables

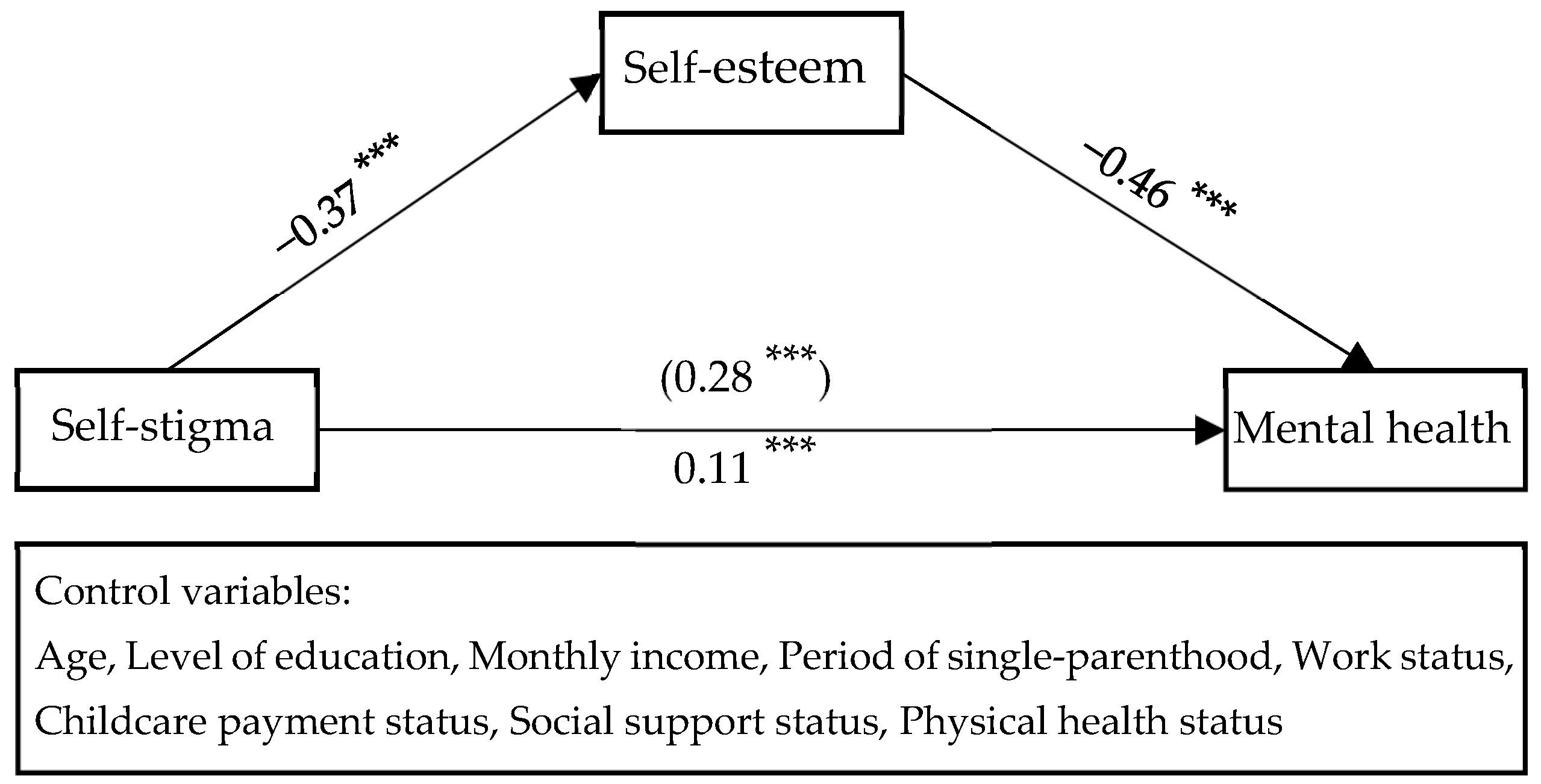

3.2. The Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem on the Effect of Self-Stigma on Mental Health

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, J.; Avison, W.R. Employment transitions and psychological distress the contrasting experiences of single and married mothers. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, A.M.; Knoester, C. Marital status, gender, and parents’ psychological well-being. Sociol. Inq. 2007, 77, 264–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good Gingrich, L. Single mothers, work(fare), and managed precariousness. J. Progress. Hum. Serv. 2010, 21, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLanahan, S.S. Family structure and stress: A longitudinal comparison of two-parent and female-headed families. J. Marriage Fam. 1983, 45, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peden, A.R.; Rayens, M.K.; Hall, L.A.; Grant, E. Negative Thinking and the Mental Health of Low-Income Single Mothers. J. Nurs. Sch. 2004, 36, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caragata, L.; Liegghio, M. Mental health, welfare reliance, and lone motherhood. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2013, 32, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Thomson, H.; Fenton, C.; Gibson, M. Lone parents, health, wellbeing and welfare to work: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.; Kelly, G. Constructing the “good” mother: Pride and shame in lone mothers’ narratives of motherhood. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 42, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.; Kelly, G. Mams, moms, mums: Lone mothers’ accounts of management strategies. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2022, 17, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.C.; Walker, R.; Richard, P.; Younis, M. Inequalities in poverty and income between single mothers and fathers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, R.J.; Meredith, A. The impact of financial hardship on single parents: An exploration of the journey from social distress to seeking help. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2018, 39, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collings, S.; Jenkin, G.; Carter, K.; Signal, L. Gender differences in the mental health of single parents: New Zealand evidence from a household panel survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufur, M.J.; Howell, N.C.; Downey, D.B.; Ainsworth, J.W.; Lapray, A.J. Sex differences in parenting behaviors in single-mother and single-father households. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 1092–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullin, S.; Harkness, S. The Single Motherhood Penalty as a Gender Penalty: Comment on Brady, Finnigan, and Hübgen. Am. J. Sociol. 2021, 127, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifcher, J.; Zarghamee, H. The happiness of single mothers: Evidence from the general social survey. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 1219–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Rao, D. On the self-stigma of mental illness: Stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Watson, A.C.; Barr, L. The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 25, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zartler, U. How to deal with moral tales: Constructions and strategies of single-parent families. J. Marriage Fam. 2014, 76, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstam, V.; Karwin, S.; Curran, T.; Lyons, M.; Celen-Demirtas, S. Stigma and divorce: A relevant lens for emerging and young adult women? J. Divorce Remarriage 2016, 57, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Conceiving the Self; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bleidorn, W.; Schwaba, T.; Denissen, J.J.; Hopwood, C.J. Charting self-esteem during marital dissolution. J. Personal. 2021, 89, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, D.B.; Harbaugh, B.L. Psychosocial differences related to parenting infants among single and married mothers. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2010, 33, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symoens, S.; Van de Velde, S.; Colman, E.; Bracke, P. Divorce and the multidimensionality of men and women’s mental health: The role of social-relational and socio-economic conditions. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2014, 9, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfhag, K.; Tynelius, P.; Rasmussen, F. Self-esteem links in families with 12-year-old children and in separated spouses. J. Psychol. 2010, 144, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keim, S. Are Lone Mothers Also Lonely Mothers? Social Networks of Unemployed Lone Mothers in Eastern Germany. In Lone Parenthood in the Life Course; Bernardi, L., Mortelmans, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 8, pp. 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; McGuire, K. ‘They’d already made their minds up’: Understanding the impact of stigma on parental engagement. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2021, 42, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Bink, A.B.; Schmidt, A.; Jones, N.; Rüsch, N. What is the impact of self-stigma? Loss of self-respect and the “why try” effect. J. Ment. Health 2016, 25, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowislo, J.F.; Orth, U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankham, C.; Richardson, T.; Maguire, N. Psychological factors associated with financial hardship and mental health: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 77, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, J.; Rayens, M.K.; Peden, A.R.; Hall, L.A. Predictors of depression for low-income African American single mothers. J. Health Disparities Res. Pract. 2008, 2, 89–110. Available online: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp/vol2/iss3/6 (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Atkins, R. Depression in black single mothers: A test of a theoretical model. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 37, 812–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Z.E.; Conger, R.D. Promoting strengths and resilience in single-mother families. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipman, E.L.; Kenny, M.; Jack, S.; Cameron, R.; Secord, M.; Byrne, C. Understanding how education/support groups help lone mothers. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Song, D. A study on the factors affecting changes in subjective health condition among single parents-focusing on family, economic, and social discrimination factors-. Korean J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2019, 65, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Re-defining stigmatization: Intersectional stigma of single mothers in Thailand. J. Fam. Stud. 2022, 29, 1222–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Mothers left without a man: Poverty and single parenthood in China. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunanayake, D.D.K.S.; Aysha, M.N.; Vimukthi, N. The Psychological Well-Being of Single Mothers with School age Children: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Kim, H. Effects of social exclusion on depression of single-parent householders. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 31, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. The Effects of Gender Role Attitudes and Family Service Utilization on Self-Esteem among Single Parents. Korean J. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Association between discrimination and self-rated health among single-mothers. J. Local Hist. Cult. 2019, 22, 487–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D.N.; Booth, A. Unhappily ever after: Effects of long-term, low-quality marriages on well-being. Soc. Forces 2005, 84, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, K. Describing Being a Single Parent of Multiples. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 12, 1310–1320. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/describing-being-single-parent-multiples/docview/2363844566/se-2 (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Goldberg, D.P.; Hillier, V.F. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol. Med. 1979, 9, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, Y.; Cho, M. Factor Structure of the 12-Item General Health Questionnaire in the Korean General Adult Population. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2012, 51, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, W.W.; Cheung, R.Y. Self-stigma among concealable minorities in Hong Kong: Conceptualization and unified measurement. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image, Rev. ed.; Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, CT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, P.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, T.J. Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach to Design and Evaluation; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, D.L.; Bitman, R.L.; Hammer, J.H.; Wade, N.G. Is stigma internalized? The longitudinal impact of public stigma on self-stigma. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitz, A.K. Self-esteem development and life events: A review and integrative process framework. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2022, 16, e12709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Self-esteem and identities. Sociol. Perspect. 2014, 57, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollmann-Schult, M. Single motherhood and life satisfaction in comparative perspective: Do institutional and cultural contexts explain the life satisfaction penalty for single mothers? J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 2061–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodermans, A.K.; Botterman, S.; Havermans, N.; Matthijs, K. Involved fathers, liberated mothers? Joint physical custody and the subjective well-being of divorced parents. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 122, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauserman, R. A meta-analysis of parental satisfaction, adjustment, and conflict in joint custody and sole custody following divorce. J. Divorce Remarriage 2012, 53, 464–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biblarz, T.J.; Stacey, J. How does the gender of parents matter? J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrova, O.; Fetchenhauer, D. Single Parents, Unhappy Parents? Parenthood, Partnership, and the Cultural Normative Context. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2015, 46, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 20 s | 6 (1.75%) |

| 30 s | 76 (21.9%) | |

| 40 s | 202 (58.2%) | |

| 50 s | 62 (17.9%) | |

| Over 60 s | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Level of education | Elementary school | 4 (1.2%) |

| Middle school | 21 (6.1%) | |

| High school | 181 (52.2%) | |

| Two year college | 76 (21.9%) | |

| Four year university | 63 (18.2%) | |

| Graduate or higher | 2 (0.6%) | |

| Monthly income (KRW) * | No income | 20 (5.8%) |

| less than one million won | 92 (26.5%) | |

| one million won~two million won | 208 (59.9%) | |

| two million won~three million won | 22 (6.3%) | |

| three million won~four million won | 1 (0.3%) | |

| four million won~five million won | 2 (0.6%) | |

| more five million won | 2 (0.6%) | |

| Period of single parenthood | less than 3 years | 102 (29.4%) |

| more than 3 to less than 5 years | 60 (17.3%) | |

| 5 to less than 10 years | 115 (33.1%) | |

| more than 10 years | 70 (20.2%) | |

| Work status | Currently working | 248 (71.5%) |

| Currently not working | 99 (28.5%) | |

| Child support payment status | Have received more than once | 171 (49.3%) |

| Had never received | 176 (50.7%) | |

| Social support status | Have social support | 228 (65.7%) |

| None | 119 (34.3%) | |

| Physical health status | Very poor | 51 (14.7%) |

| Poor | 90 (25.9%) | |

| Fair | 156 (45.0%) | |

| Good | 42 (12.1%) | |

| Very good | 8 (2.3%) |

| 1. Mental Health | 2. Self-Stigma | 3. Self-Esteem | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mental health | 1 | ||

| 2. Self-stigma | 0.53 ** | 1 | |

| 3. Self-esteem | −0.74 ** | −0.54 ** | 1 |

| Mean (M) | 2.98 | 2.69 | 3.08 |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | 0.54 | 0.93 | 0.67 |

| Range | 1–4 | 1–5 | 1–5 |

| Skewness | 0.10 | 0.16 | −0.28 |

| Kurtosis | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Variable | Dependent Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | Self-Esteem | Mental Health | |||||

| B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI | ||

| CV | Age | −0.11 ** (0.03) | [−0.18, −0.04] | 0.17 *** (0.04) | [0.08, 0.26] | −0.03 (0.03) | [−0.09, 0.02] |

| Level of education | −0.03 (0.02) | [−0.08, 0.02] | 0.09 ** (0.03) | [0.03, 0.15] | 0.01 (0.02) | [−0.03, 0.06] | |

| Monthly income | −0.01 (0.03) | [−0.07, 0.06] | −0.06 (0.04) | [−0.14, 0.02] | 0.01 (0.03) | [−0.08, 0.02] | |

| Period of single-parenthood | −0.01 (0.02) | [−0.05, 0.03] | 0.01 (0.03) | [−0.04, 0.07] | −0.01 (0.02) | [−0.04, 0.03] | |

| Work status | 0.04 (0.06) | [−0.07, 0.15] | 0.03 (0.07) | [−0.11, 0.17] | 0.06 (0.05) | [−0.03, 0.15] | |

| Childcare payment status | 0.00 (0.05) | [−0.09, 0.09] | −0.05 (0.06) | [−0.16, 0.07] | −0.02 (0.04) | [−0.09, 0.05] | |

| Social support status | −0.10 (0.05) | [−0.19, −0.00] | 0.04 (0.06) | [−0.09, 0.16] | −0.08 (0.04) | [−0.16, −0.00] | |

| Physical health status | −0.21 *** (0.03) | [−0.26, −0.16] | 0.17 *** (0.03) | [0.11, 0.24] | −0.13 *** (0.02) | [−0.17, −0.08] | |

| IV | Self-stigma | 0.28 *** (0.02) | [0.23, 0.32] | −0.37 *** (0.03) | [−0.42, −0.30] | 0.11 *** (0.02) | [0.06, 0.15] |

| MV | Self-esteem | −0.46 *** (0.03) | [−0.53, −0.39] | ||||

| F | 28.74 *** (0.43) | 23.78 *** (0.39) | 57.38 *** (0.63) | ||||

| Path | B | Boot SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |||

| Self-stigma→Self-esteem→Mental health | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, A.; Jeon, S.; Song, J. Self-Stigma and Mental Health in Divorced Single-Parent Women: Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090744

Kim A, Jeon S, Song J. Self-Stigma and Mental Health in Divorced Single-Parent Women: Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(9):744. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090744

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Anna, Sesong Jeon, and Jina Song. 2023. "Self-Stigma and Mental Health in Divorced Single-Parent Women: Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 9: 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090744

APA StyleKim, A., Jeon, S., & Song, J. (2023). Self-Stigma and Mental Health in Divorced Single-Parent Women: Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090744