Association between Electronic Media Use and Internalizing Problems: The Mediating Effect of Parent–Child Conflict and Moderating Effect of Children’s Age

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Electronic Media Use and Internalizing Problems

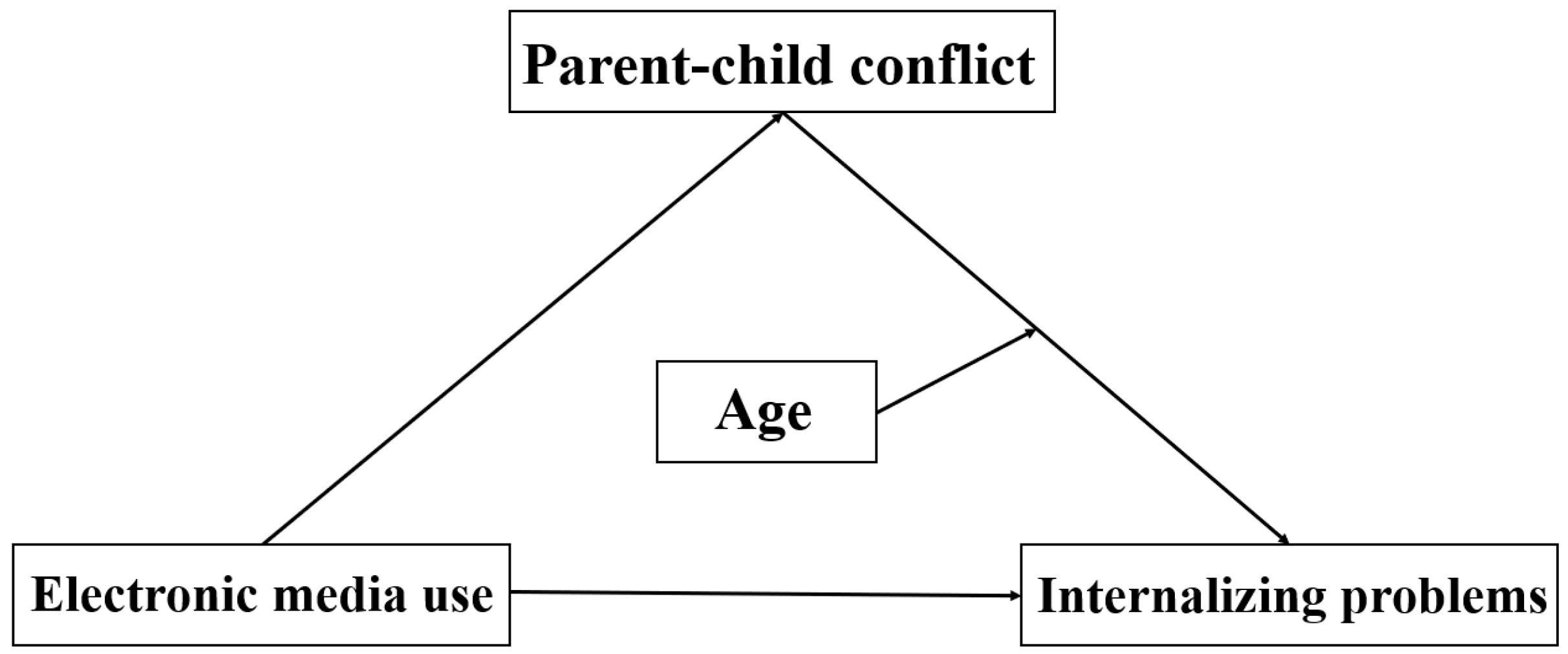

1.2. The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Conflict

1.3. The Moderating Role of Children’s Age

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Respondents

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Electronic Media Use

2.2.2. Parent–Child Conflict

2.2.3. Internalizing Problems

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

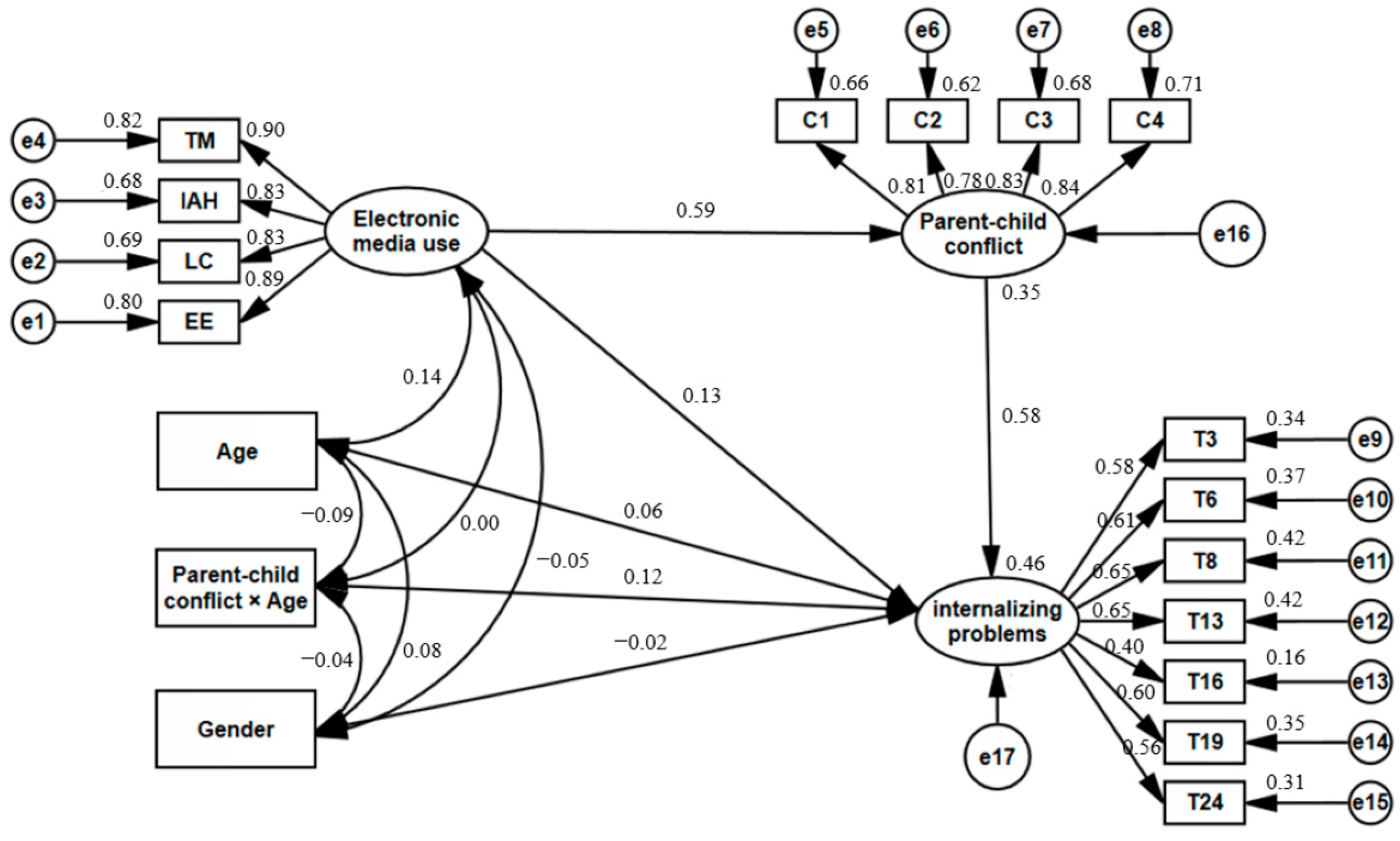

3.4. Moderated Mediation Effect Test

4. Discussion

4.1. Electronic Media Use and Internalizing Problems

4.2. The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Conflict

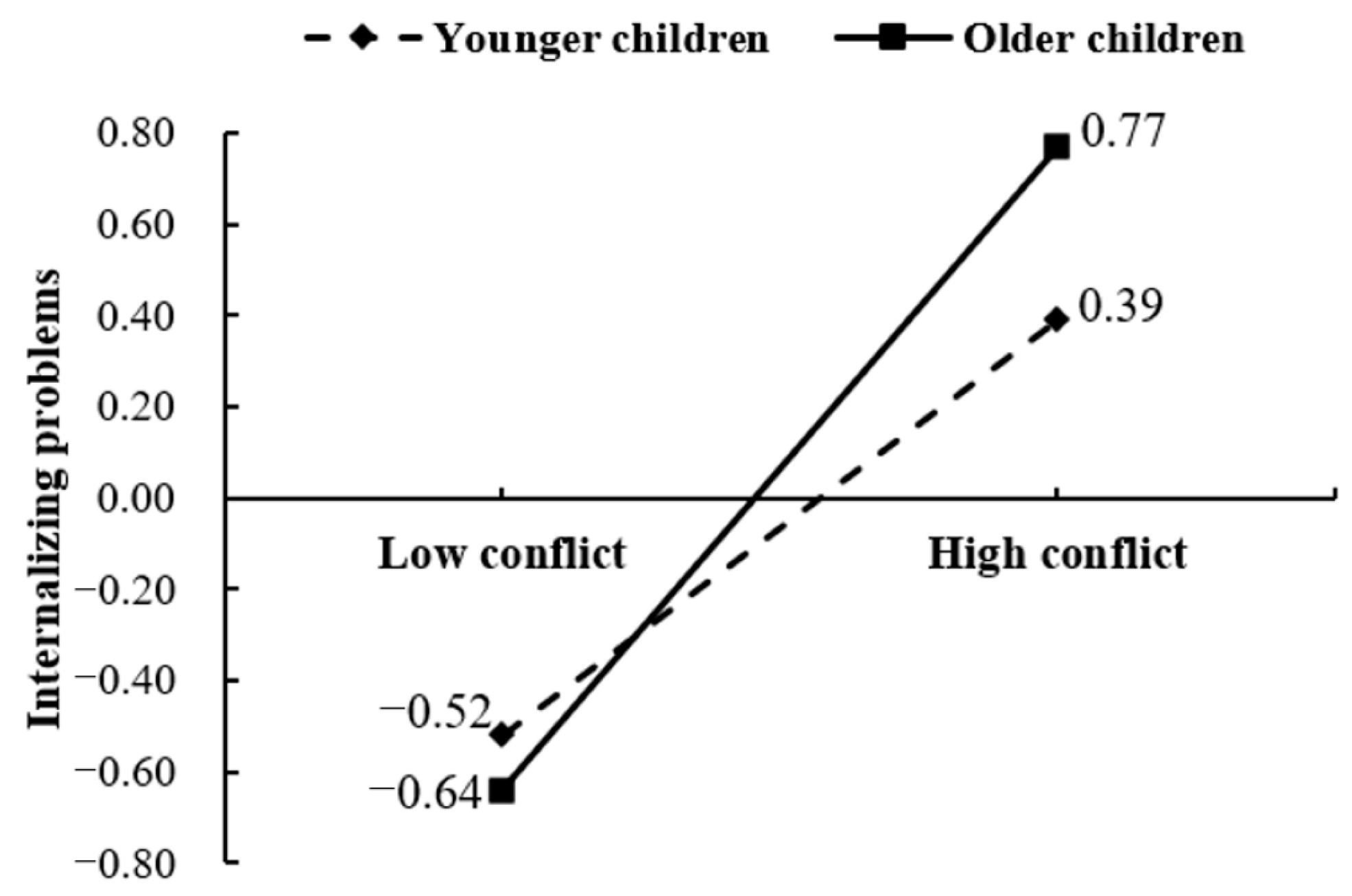

4.3. The Moderating Effects of Age

4.4. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lulla, D.; Mascarenhas, S.S.; How, C.H.; Yeleswarapu, S.P. An approach to problem behaviours in children. Singap. Med. J. 2019, 60, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, L.; Hale, D.; Barker, E.D.; Viner, R. Conduct problems trajectories and psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 1239–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lougheed, J.P.; Duncan, R.J.; Keskin, G.; Marceau, K. Longitudinal associations between mother-child conflict and child internalizing problems in mid-childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2022, 34, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, L.M.; Trentacosta, C.J.; Aikins, D.; Wargo-Aikins, J. Maternal emotion regulation and children’s behavior problems: The mediating role of child emotion regulation. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 2797–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Bullock, A.; Coplan, R.J.; Liu, J.; Cheah, C.S.L. Exploring the relations between parenting practices, child shyness, and internalizing problems in Chinese culture. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Jiang, J.N.; Chen, M.M.; Liu, J.Y.; Ma, T.; Ma, Q.; Cu, M.J.; Guo, T.J.; et al. Association of body fat distribution with depression and social anxiety in children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study based on dual-energy X-ray detection. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2023, 55, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.W.; Bullock, A.; Liu, J.S.; Coplan, R.J. The longitudinal links between marital conflict and Chinese children’s internalizing problems in mainland China: Mediating role of maternal parenting styles. Fam. Process 2022, 61, 1749–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.M.; Molyneaux, E.; Dennis, C.L.; Rochat, T.; Stein, A.; Milgrom, J. Perinatal mental health 1 Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet 2014, 384, 1775–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Cao, H.J.; Leerkes, E.M. Interparental conflict and infants’ behavior problems: The mediating role of maternal sensitivity. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, S.H.; Rapee, R.; McDonald, C.; Ingram, M. The structure of anxiety symptoms among preschoolers. Behav. Res. Ther. 2001, 39, 1293–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, O.L.; Degnan, K.A.; Fox, N.A.; Henderson, H.A. Social problem solving in early childhood: Developmental change and the influence of shyness. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 34, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bongers, I.L.; Koot, H.M.; van der Ende, J.; Verhulst, F.C. The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, M.O.; Yoon, D.; Minnes, S.; Ridenour, T.; Singer, L.T. Profiles of individual assets and mental health symptoms in at-risk early adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2019, 75, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, S.; Doane, L.D.; Breitenstein, R.; Grimm, K.J.; Lemery-Chalfant, K. Effortful control moderates the relation between electronic-media use and objective sleep indicators in childhood. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brushe, M.E.; Islam, T.; Monroy, N.S.; Sincovich, A.; Gregory, T.; Finlay-Jones, A.; Brinkman, S.A. Prevalence of electronic device use before bed among Australian children and adolescents: A cross-sectional population level study. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 46, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkley, T.; Verbestel, V.; Ahrens, W.; Lissner, L.; Molnar, D.; Moreno, L.A.; Pigeot, I.; Pohlabeln, H.; Reisch, L.A.; Russo, P.; et al. Early childhood electronic media use as a predictor of poorer well-being: A prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunborg, G.S.; Mentzoni, R.A.; Froyland, L.R. Is video gaming, or video game addiction, associated with depression, academic achievement, heavy episodic drinking, or conduct problems? J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, W. COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on increasing the risks of children’s addiction to electronic games from a social work perspective. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R.; Patterson, M.; Lundmark, V.; Kiesler, S.; Mukopadhyay, T.; Scherlis, W. Internet paradox—A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aierbe, A.; Oregui, E.; Bartau, I. Video games, parental mediation and gender socialization. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2019, 36, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.Q.; Zhu, Y.H.; Wang, J.Y.; Dong, H.Q. Parent-child conflict and friendship quality of Chinese adolescence: The mediating role of resilience. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlie, C.W.D.; Hyekyung, C.; Khoo, A. Role of parental relationships in pathological gaming. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Sykes, T.A.; Chan, F.K.Y.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Hu, P.J.H. Children’s internet addiction, family-to-work conflict, and job outcomes: A study of parent-child dyads. MIS Q. 2019, 43, 903–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Moreira, H.; Canavarro, M.C. Uncovering the links between parenting stress and parenting styles: The role of psychological flexibility within parenting and global psychological flexibility. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 18, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.T.; Cummings, E.M. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, I. Attachment theory: Retrospect and prospect. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1985, 50, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, N.; Howard, A.H.; Morgan, M.; Hardin, M. Adverse childhood experiences and problematic media use: The roles of attachment and impulsivity. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2020, 15, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippold, M.A.; Hussong, A.; Fosco, G.; Ram, N. Youth internalizing problems and changes in parent–child relationships across early adolescence: Lability and developmental trends. J. Early Adolesc. 2021, 41, 472–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelau, J. Biologically determined dimensions of personality or temperament. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1982, 3, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N. Ecological systems theory: The person in the center of the circles. Res. Hum. Dev. 2007, 4, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.M.; Wang, J.T. The relationship between family atmosphere children’s life satisfaction and intergenerational transmission of mental health: The difference of parent-child gender and children age. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2022, 20, 282–288. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, J.G.; Campione-Barr, N.; Metzger, A. Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 255–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.Y. The role of attachment style in building social capital from a social networking site: The interplay of anxiety and avoidance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Koh, E. Avoidant attachment and smartphone addiction in college students: The mediating effects of anxiety and self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xie, W.J. Teens’ concern for privacy when using social networking sites: An analysis of socialization agents and relationships with privacy-protecting behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 33, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, M.F. Parental harsh discipline and adolescent problem behavior in China: Perceived normativeness as a moderator. Child Abuse Negl. 2018, 86, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, A.S.; Zeytinoglu, S.; Leerkes, E.M. When is parental suppression of black children’s negative emotions adaptive? The role of preparation for racial bias and children’s resting cardiac vagal tone. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2022, 50, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishstrom, S.; Wang, H.H.; Bhat, B.H.; Daniel, J.; Dille, J.; Capin, P.; Vaughn, S. A meta-analysis of the effects of academic interventions on academic achievement and academic anxiety outcomes in elementary school children. J. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 92, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouri, E.; Midouhas, E. Environmental adversity and children’s early trajectories of problem behavior: The role of harsh parental discipline. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Q.; Zhou, Y.; Qu, F.B.; Liu, X.C. The Role of Parenting Styles and Parents’ Involvement in Young Children’s Videogames Use. In Proceedings of the HCI in Games: Second International Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Parent-child and teacher-child relationships in Chinese preschoolers: The moderating role of preschool experiences and the mediating role of social competence. Early Child. Res. Q. 2011, 26, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, M.A.; Saglam, M.; Ozdemir, F.; Ucuz, I.; Bugday, B. The effect of physical activity on mother-child relationship and parental attitudes: A follow-up study examining the long-term effects of COVID-19. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 4299–4308. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, H.C.; Zhang, G.F.; Zhou, B.F.; Wu, W. A longitudinal study of parent–child relationships and problem behaviors in early childhood: Transactional models. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2008, 5, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarø, L.E.; Davids, E.L.; Mathews, C.; Wubs, A.G.; Smith, O.R.F.; de Vries, P.J. Internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and prosocial behavior—Three dimensions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): A study among South African adolescents. Scand. J. Psychol. 2022, 63, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Goodman, R. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Smith, R.; O’Farrelly, C.; Iles, J.; Rosan, C.; Ryan, R.; Ramchandani, P. Assessing behavior in children aged 12-24 months using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Infancy 2021, 26, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice-Stam, H.; Haverman, L.; Splinter, A.; van Oers, H.A.; Schepers, S.A.; Grootenhuis, M.A. Dutch norms for the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)—Parent form for children aged 2–18 years. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.D.; Wen, Z.L. Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: Problems and suggestions. J. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K.F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wen, Z.L. Item parceling strategies in structural equation modeling. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 19, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga, M. Item parceling in structural equation modeling: A primer. Commun. Methods Meas. 2008, 2, 260–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.J.; Wang, H.Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhan, P.P.; Wang, J.L. Childhood maltreatment, basic psychological needs satisfaction, internet addiction and internalizing problems. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 86, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.A. Longitudinal effect of social withdrawal on negative peer relations mediated by smartphone dependence among Korean early adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.C.; Lan, N.N.; Zhang, H.B.; Sun, X.J.; Zhang, Y. How does social anxiety affect Mobile phone dependence in adolescents? The mediating role of self-concept clarity and self-esteem. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 8070–8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V.A.; Marchante, M.; Romao, A.M. Adolescents’ trajectories of social anxiety and social withdrawal: Are they influenced by traditional bullying and cyberbullying roles? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 69, 102053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, A.M.; Careaga, J.S.; Mehl, M.R.; O’Connor, M.F. Social engagement and user immersion in a socially based virtual world. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Rauti, S.; Islam, A.; Sutinen, E. Why playing augmented reality games feels meaningful to players? The roles of imagination and social experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, K.; Martins, N. A content analysis of American primetime television: A 20-year update of the national television violence studies. J. Commun. 2022, 72, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchioni, E.; Santoni, C. The youth on-line life: Risks, violence and support networks. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2022, 32, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, P.; Appel, M. Internet use and video gaming predict problem behavior in early adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Dong, G.; Wang, Q.; Du, X. Abnormal gray matter and white matter volume in ‘Internet gaming addicts’. Addict. Behav. 2015, 40, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axmacher, N.; Elger, C.E.; Fell, J. Working memory-related hippocampal deactivation interferes with long-term memory formation. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 1052–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, L.; Zhou, R.; Jiang, Y. Working memory training improves emotion regulation ability: Evidence from HRV. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 155, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.W.; Bolland, J.M.; Dick, D.; Mustanski, B.; Kertes, D.A. Effect of environmental risk and externalizing comorbidity on internalizing problems among economically disadvantaged African American youth. J. Res. Adolesc. 2016, 26, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Coyne, S.M. Technology interference in the parenting of young children: Implications for mothers’ perceptions of coparenting. Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 53, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, J.D.; Tan, Y.W.; Cao, Y.R.; Kato, N. Automatic content inspection and forensics for children android apps. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 7123–7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhu, W.M.; Sun, X.T.; Huang, L. Internet addiction and child physical and mental health: Evidence from panel dataset in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 309, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.P.; Shen, A.C.T.; Wei, H.S.; Feng, J.Y.; Huang, S.C.Y.; Hwa, H.L. Internet addiction: A closer look at multidimensional parenting practices and child mental health. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y. Overparenting, parent–child conflict and anxiety among Chinese adolescents: A cross-lagged panel study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anicama, C.; Zhou, Q.; Ly, J. Parent involvement in school and Chinese American children’s academic skills. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 111, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwairy, M.; Achoui, M.; Abouserie, R.; Farah, A.; Sakhleh, A.A.; Fayad, M.; Khan, H.K. Parenting styles in Arab societies—A first cross-regional research study. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2006, 37, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, I.; Garcia, J.F. Internalization of values and self-esteem among brazilian teenagers from authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful homes. Adolescent 2008, 43, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Widman, S.; Roque, R. Family Negotiation in Joint Media Engagement with Creative Computing. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, R.; Lee, K.J.; Choi, Y.J. Mobile phone overuse among elementary school students in Korea factors associated with mobile phone use as a behavior addiction. J. Addict. Nurs. 2015, 26, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikken, P.; Schols, M. How and why parents guide the media use of young children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 3423–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.C. Education video games in China. Multiling. Comput. Technol. 2010, 21, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.A.; Johnson, S.L.; Vandewater, E.A.; Schmiege, S.J.; Boles, R.E.; Lev, J.; Tschann, J.M. Parenting and preschooler TV viewing in low-income Mexican Americans: Development of the parenting practices regarding TV viewing (PPRTV) Scale. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2016, 37, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpin, S.; Mitchell, A.E.; Baker, S.; Morawska, A. Parenting and child behaviour barriers to managing screen time with young children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons-Ruth, K.; Pechtel, P.; Yoon, S.A.; Anderson, C.M.; Teicher, M.H. Disorganized attachment in infancy predicts greater amygdala volume in adulthood. Behav. Brain Res. 2016, 308, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; de Haan, M. Annual Research Review: Parenting and children’s brain development: The end of the beginning. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lollis, S.; Kuczynski, L. Beyond one hand clapping: Seeing bidirectionality in parent–child relations. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 1997, 14, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Zadurian, N. Exploring the links between parental attachment style, child temperament and parent–child relationship quality during adolescence. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeus, W. Adolescent psychosocial development: A review of longitudinal models and research. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 1969–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudat, S.; Van Petegem, S.; Antonietti, J.P.; Zimmermann, G. Parental solicitation and adolescents’ information management: The moderating role of autonomy-supportive parenting. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcone, R.; Affuso, G.; Borrone, A. Parenting styles and children’s internalizing-externalizing behavior: The mediating role of behavioral regulation. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, E.; Buchanan, D.; Quick, L. “Look at them! They all have friends and not me”: The role of peer relationships in schooling from the perspective of primary children designated as “lower-attaining”. Educ. Rev. 2022, 74, 1224–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, A.; Chai, W.Y.; Halstead, E.; Dimitriou, D.; Esposito, G. An exploratory analysis of the effect of demographic features on sleeping patterns and academic stress in adolescents in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Ren, W.T.; Liang, Z.R. Perceived academic stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation analysis of overweight status. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 296, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, X.O.; Liu, J.T.; Bai, Y.T. The influence of discrepancies between parents’ educational aspirations and children’s educational expectations on depressive symptoms of left-behind children in rural China: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, S.; Fujisawa, T.X.; Kojima, M.; Tomoda, A. Type and timing of negative life events are associated with adolescent depression. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Father | Mother | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 34.10 years (SD = 5.11) | 32.34 years (SD = 4.62) |

| Education (%) | ||

| Primary and below | 0.4% | 0.6% |

| Junior high | 2.4% | 2.2% |

| Senior high and middle school | 9.3% | 8.6% |

| College and bachelor’s degree | 70.6% | 78.4% |

| Postgraduate and above | 17.4% | 10.3% |

| Occupation (%) | ||

| Managers | 25.5% | 18.5% |

| Professionals and technicians | 20.1% | 15.3% |

| Clerical support workers | 8.6% | 9.1% |

| Service and sales workers | 11.5% | 13.7% |

| Skilled agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers | 1.6% | 0.6% |

| Craft and related trades workers | 2.6% | 1.0% |

| Armed forces occupations | 2.2% | 0.3% |

| Full-time parents | 0.6% | 13.4% |

| Unemployed | 0.9% | 1.9% |

| Freelancers | 26.3% | 26.3% |

| Monthly income (%) | ||

| ≤2999 CNY | 1.9% | 12.8% |

| 3000–5999 CNY | 15.0% | 25.9% |

| 6000–8999 CNY | 29.6% | 32.6% |

| 9000–11,999 CNY | 25.9% | 17.7% |

| ≥12,000 CNY | 27.6% | 11.0% |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.52 | 0.50 | — | ||||

| 2. Age | 5.23 | 1.91 | — | 1 | |||

| 3. Electronic media use | 33.19 | 10.68 | −0.05 | 0.15 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. Parent–child conflict | 25.97 | 8.29 | −0.09 * | 0.04 | 0.53 ** | 1 | |

| 5. Internalizing problems | 2.66 | 2.53 | −0.08 * | 0.07 | 0.42 ** | 0.54 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geng, S.; Xu, K.; Liu, X. Association between Electronic Media Use and Internalizing Problems: The Mediating Effect of Parent–Child Conflict and Moderating Effect of Children’s Age. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080694

Geng S, Xu K, Liu X. Association between Electronic Media Use and Internalizing Problems: The Mediating Effect of Parent–Child Conflict and Moderating Effect of Children’s Age. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):694. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080694

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeng, Shuliang, Ke Xu, and Xiaocen Liu. 2023. "Association between Electronic Media Use and Internalizing Problems: The Mediating Effect of Parent–Child Conflict and Moderating Effect of Children’s Age" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080694

APA StyleGeng, S., Xu, K., & Liu, X. (2023). Association between Electronic Media Use and Internalizing Problems: The Mediating Effect of Parent–Child Conflict and Moderating Effect of Children’s Age. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080694