Abstract

Employee health is crucial to organizational success. However, workplace ostracism (WO) has significant negative effects on employee health. Numerous researchers have extensively examined how WO influences employees’ negative health (job stress, burnout); however, the focus on mediating effects in the relationship between WO and health has been lacking. This study examined the cognitive evaluation response to WO by employees who perceive they have been ostracized because another employee envies them. The psychological defense mechanism is expected to be activated—thus triggering job stress and burnout. We investigated envy perceived by individuals as a mediator of WO, job stress, and burnout using data from a 2-wave longitudinal survey of 403 employees of a South Korean firm. We found that employees perceived WO. Specifically, based on the sensitivity to being the target of a threatening upward comparison theory, it was confirmed that envy was a mediator in the relationship between WO and negative health outcomes. Our results are the first to show that the perception of envy can mediate the maintenance of a positive self-image in the context of WO in South Korea. The results suggest that a greater awareness of and focus on envy, and WO is required.

1. Introduction

Employees are an important human resource in organizations. Their personal health is a fundamental issue at the organizational level. However, results from the scientific literature indicate that ostracization causes psychological pain in individuals and negatively affects their behavior and mental and physical health [1,2,3]. When high-performing workers like Ella experience psychological distress, such as stress or burnout, their self-esteem is lowered, and their health suffers [1,4]. This causes disruptions in their work progress and eventually results in additional costs for the organization. As such, it is important to focus on employees’ health in relation to workplace ostracism (hereafter, “WO”).

Recently, WO has been recognized as a severe organizational problem behavior [5]. Previous studies have found that a surprisingly large number of people are being ostracized within their organizations. For example, in a study on how being ostracized by co-workers affects people’s attitudes and behaviors at work, 13% of the survey respondents reported experiencing some neglect or rejection [6]. Another study by Fox and Stallworth [7], in which 66% of respondents reported experiencing a similar experience of bullying, suggested that bullying in organizations is currently a behavior that anyone can engage in. Workplace bullying has, therefore, become prevalent [8].

Why do problem behaviors, such as WO, become widespread in organizations? One reason is that ostracism is an unobtrusive behavior and, therefore, is not subject to punitive action [4]. Thus, WO can be problematic because it is likely to persist among coworkers for a long time. Nevertheless, WO as an organizational behavior remains relatively unexplored, and many unresolved research questions have been raised [5]. South Korea, a small but strong country that has rapidly become prosperous, has the stigma of having the highest suicide rate among the OECD countries [9]. As extreme incidents have recently occurred due to WO, its cause should be identified through further research; hence, it is timely to study the cause and mechanism of WO by targeting office workers in South Korea.

Our study aims to examine WO as a mechanism of job stress and burnout affecting employees’ health and suggest theoretical and practical implications for organizations. We argue that individual perceptions of WO may differ from person to person according to their perceptions of the source of ostracism. The experience of becoming aware of WO is psychologically very painful for the victim. WO is dangerous because it is not obvious. As an individual recognizes that they are experiencing WO, the psychological defense mechanism may be activated as a cognitive evaluation reaction, with the individual perceiving that the WO is occurring because someone within their organization is envious of them. This can lead to job stress and burnout. Our argument is in line with research by Balliet and Ferris [10]. As mentioned earlier, Ella believes she is being bullied because she perceives that she is an object of envy among her peers as she is a high performer. However, it is the position that there is no need to react negatively or repulsively to her perception itself [5]. Individuals activate cognitive thinking about themselves in threatening situations, such as social exclusion, in an attempt to determine the reasons behind the threat. Meaningful actions are then based on these reasons [11].

To support these arguments, we suggest a research model based on social comparison. When individuals face complex or ambiguous situations such as WO, they compare themselves with others to convince themselves of their reality [12]. For example, in Ella’s case, the situation in which she was being ostracized made her believe that her co-workers envied her work-related success and the approval of her superiors. This is because when humans encounter undesirable social information, such as ostracizing, they momentarily perceive it as a threat, and their self-protection becomes important [13,14,15]. This process is at the core of our study. Humans activate the “psychological immune system” when they infer or rationalize why someone is doing something to them in a threatening and uncomfortable situation [16]; that is, when there is a detrimental effect on an individual, they offset negative social experiences by focusing on success (e.g., [17,18]). Through this mechanism, employees who believe they are successful at work and contribute to the organization may perceive themselves as objects of envy by their peers [19,20].

To date, studies related to ostracism have mainly investigated job stress or burnout as parameters (e.g., [21,22,23,24]). We aim to go a step further and present a model that provides deeper insights by demonstrating the mediating effect of envy in the relationship between perceived ostracization and stress or burnout. This study aimed to demonstrate that WO positively (+) affects employees’ job stress and burnout and that an individual’s perception of themselves as an object of envy has a mediating effect between WO and employee health outcomes (job stress and burnout). This mediating effect is a unique perspective that has not yet been explored in WO research. We aim to make theoretical and practical contributions to the development of WO research by identifying gaps in the current literature regarding the mediating effect of the perception of envy.

2. Theoretical Background

When people are mistreated, they attempt to understand the reasons for this mistreatment [25]. Employees who are aware of ostracism in their organizations are no exception; they also look for a reason for being ostracized. As a result, among the various interactions that occur in interpersonal relationships, the interpretation of a discretionary phenomenon such as WO affects individual responses [26]: the victim of WO will likely determine a reason for being a target, and this recognition will affect their job stress and burnout as aspects of their personal health.

When an employee achieves exceptional job performance, they may become the object of envy in the workplace [27]. Interestingly, as humans are likely to falsely perceive that others envy them [28]; although this may not be the case, this perception can occur even if the employee is not necessarily a high-performing worker. Thus, this study focuses on individual perceptions that influence one’s reactions rather than the objective characteristics of the reality in the workplace. How an individual perceives reality or a phenomenon influences their subsequent behaviors and psychological health (cf. Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson’s [29] meta-analysis results [30,31]); therefore, we argue that when an individual who experiences WO perceived that they are the object of envy, the resulting emotional response harms their health [32,33,34].

2.1. Workplace Ostracism

WO has been studied under organizational behavior since the 1970s [35] and has been treated as an abnormal social phenomenon. Negative social phenomena similar to WO include organizational misbehavior [36], antisocial behavior [37], aggression [38], dysfunctional behavior [39], workplace deviance [40], counterproductive work behavior [41], social undermining [42], and workplace bullying [7,43]. Although ostracism has long been studied in various social science fields [44], the separate distinction of “in the workplace” is added in the context of organizational behavior to emphasize its importance. As a concept, it has been defined by Robinson, O’Reilly, and Wang [45] as “an individual or group within the workplace that decides that it is socially acceptable to do so, omitting the participation of a specific member”. One example is treating a particular member of the organization as invisible, which includes omitting ambiguous behaviors, such as not making eye contact with them or not inviting them to formal or informal gatherings within the team [3].

Although highly undesirable and a negative social phenomenon among employees, WO differs from other dysfunctional behaviors in organizations that include acts of exclusion, workplace harassment, incivility, bullying, deviance, and social undermining [45], which can largely be observed as interactions. In contrast, WO is characterized as being non-interactional and not blunt or overt; in other words, openly negative words or actions are not included in this behavior [45]. WO is more ambiguous than other dysfunctional behaviors [8]; hence, it is much more challenging to deal with and can be more threatening than incivility, harassment, or bullying. As such, O’Reilly et al. [46] suggest that ostracism is more harmful than other forms of workplace abuse. More research is needed on WO because of its possible potential adverse effects on employees; however, it has received relatively little attention to date [1].

2.2. Workplace Ostracism and Employees’ Negative Health Outcomes

Employees are key organizational resources, and job stress and burnout are representative negative health indicators that need to be managed. Derived from the Latin word “stringere”, meaning narrow or suppressed, the word stress was first used in the 14th century. Stress occurs in objective interactions but as a subjective experience [47]. It refers to the physical and psychological reactions that occur when pressure or threat is perceived. Among various stresses, job stress can be defined as “harmful physical and mental reactions that occur when job requirements do not match the ability, resources, or desires of workers” (International Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, NIOSH). Job stress can significantly impact individual health [48], with all job stress parameters explaining 41% of general health-related changes [49]. Burnout is a state of chronic stress that involves an individual becoming “exhausted due to excessive demands on energy, strength, or resources” at work [50]. It is defined as a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, dehumanization, and reduced achievement [51]. Therefore, we assumed that two negative aspects related to health, job stress and burnout, are important variables and examine these with WO.

WO is an interpersonal stressor [8,48,52]. Both theoretical and empirical studies support its potential negative impact on individual health. According to the conservation of resources theory (COR), individuals have limited resources that they strive to possess, protect, and further establish [53,54]. However, individuals that are aware of WO not only have to mobilize their resources to fight back but also use them in isolation. Resource depletion occurs because the likelihood of replenishment is low; therefore, employees deprived of resources because of WO are more likely to become stressed and exhausted [53]. Social support frees employees from the harmful effects of stressful experiences. As WO indicates a lack of social support, individuals who experience ostracism are less likely to cope with stressful work experiences [55,56,57].

WO is a stressor that is also consistent with affective events theory, which states that employees react emotionally to specific work events and that such emotional reactions are important determinants of employee attitudes and behaviors [58,59]. Workplace exclusion is similar to WO as it can create negative emotional states that increase the experience of stress and reduce an individual’s resources [60]. This exacerbates the imbalance between job demands and resources and increases the likelihood of burnout. The most widely reported component of burnout is a chronic state of emotional and physical exhaustion [61], which includes the feeling that one’s emotional and physical resources are overextended and depleted [62]. Emotional burnout occurs when emotional demands exceed an individual’s ability to manage interpersonal relationships [63]. Workplace ostracism constitutes a loss of resources in terms of unsupportive colleagues. Research has shown that individuals experience emotional exhaustion when they do not have sufficient resources to handle daily tasks [64]. When employees are ostracized, they lose their emotional connections with others. Humans need social interaction to share emotional feelings, strengthen emotional resources, and maintain psychological and physical health [65]. Emotional resources are lost when the need for emotional sharing is unmet, which leads to emotional burnout. This suggests a unique relationship between WO and emotional exhaustion.

Several empirical studies have revealed an association between ostracism and health. Individuals who perceive WO have lower levels of satisfaction and psychological health [1,6]. According to Wu et al. [66], it is essential to investigate the association between WO and stress-related outcomes. Ostracism is related to experiencing a lack of control over a situation that leaves the victim feeling helpless in the workplace. Overall, ostracism is considered a workplace stressor that threatens the employee’s ability to cope with work and daily life. Based on the COR theory [54] and Williams’s ostracism model [52], the following hypotheses were established regarding the effects of WO:

Hypothesis 1.

WO is strongly related to employee’s negative health outcomes.

Hypothesis 1(a).

WO is strongly related to employee’s job stress.

Hypothesis 1(b).

WO is strongly related to employee’s burnout.

2.3. Mediation Effect of Envy

When faced with the threatening situation of WO, a self-protective thought named ‘envy’ is often evoked as a coping mechanism. Envy is a unique emotion that strongly influences an individual’s behavior [67]. It cannot be seen as a simple personality trait but as a relative emotion caused by someone else [68]; therefore, an individual’s perception that they are the object of someone’s envy should also be considered a temporary and circumstantial phenomenon [67]. The individual who recognizes WO activates a perception of others’ envy as a self-protective thought, which may later lead to job stress or burnout.

To support our argument, we adopted the perspective of sensitivity to being the target of a threatening upward comparison theory in a broad framework. Upward comparison is the perception that someone has a more significant advantage than oneself [12]; it arises from a competitive paradigm with others and has negative effects on the self [69]. High-performing employees who recognize ostracism in their organizations may have self-protective thoughts that their co-workers envy their achievements and are jealous of their success. They view their image favorably because they need psychological defense mechanisms to buffer negative experiences related to ostracism [16]. Menon and Thompson [70] suggest that when individuals experience social exclusion similar to WO, they struggle to find a reason for it and attempt to make cognitive and emotional judgments about others’ motives for their exclusion. They subsequently want to maintain their positive emotions to respond to the threat [71], as WO is a painful experience, both psychologically and attitudinally, for the person concerned [71]. As such, a psychological immune system is necessary [44]. Several studies have shown that social exclusion similar to WO induces a response to defend oneself (e.g., [72,73,74]).

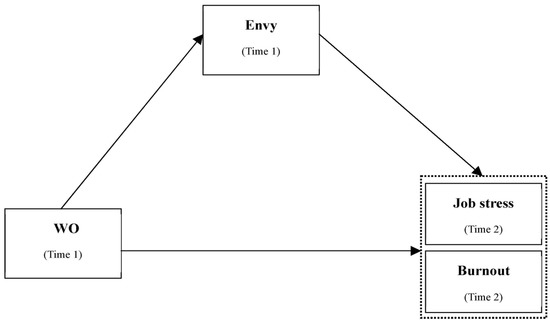

An individual’s perception that someone in their organization is envious of them can become a stressful experience that interferes with their work progress (e.g., [19,69,75]) and leads to burnout. Since the Republic of Korea is a society with a high tendency to be relationship-oriented, the negative influence of an individual’s perception of not having a good relationship with someone can be significant. Thus, an individual’s belief that they are envied by their co-workers can have a detrimental effect on their job stress and could lead to burnout. In summary, employees who believe they are experiencing WO will recognize job stress and burnout as negative influences. In this process, they will activate the perception that they are the object of envy through upward comparison as a form of psychological immunity to protect themselves. Based on the results of previous studies, the following hypotheses were established regarding the mediating effect of envy (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

This study’s theoretical model. Notes: The two variables (job stress and burnout) inside the dotted line represent Negative Health Outcomes.

Hypothesis 2.

The relationship between WO and an employee’s health outcomes is mediated by the perception that they are the target of co-worker envy.

Hypothesis 2(a).

The relationship between WO and an employee’s job stress is mediated by the perception that they are the target of co-worker envy.

Hypothesis 2(b).

The relationship between WO and an employee’s burnout is mediated by the perception that they are the target of co-worker envy.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

We conducted an online survey with 530 employees who worked at various companies in South Korea to validate the hypotheses. The online survey was available for five weeks, providing ample opportunity for participants to complete it. The first and second rounds were conducted with a one-month time difference. The total number of participants was 520 in the first survey. These 520 participants were requested to participate in the second survey, and 430 responses were received. After excluding missing values, data from 403 participants were used for the final analysis (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive features of the sample (n = 403).

To solve the problem of the common method bias [76], the survey was conducted twice with a time difference. The first survey measured workplace ostracism and envy, and the second measured job stress and burnout. By adopting this research design, we overcame the limitations of cross-sectional research.

3.2. Measures

The surveys employed a 5-point Likert scale. We translated the original English questionnaires into Korean. To ensure the reliability and validity of the research tool, we followed a standard translation and back-translation procedure [76].

WO. We measured employees’ perceptions of WO using Ferris et al.’s [1] 10-item scale. A sample item is “Others at work treated you as if you were not there”.

Envy. We measured employees’ perceptions of being envied using Vecchio’s [28] 3-item scale. A sample item is “Because of my success at work, I am sometimes resented by my coworkers”.

Job stress. We measured the employees’ perceptions of job stress using Keller’s [77] four-item scale. A sample item is “I experience stress from my job”.

Burnout. We measured employees’ perceptions of burnout using Kalliath et al.’s [78] five-item emotional exhaustion scale. A sample item is “I feel emotionally drained from my work”.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

First, we performed descriptive and correlation analyses to assess the data’s normality assumption, encompassing skewness and kurtosis statistics. No significant concerns arose during this stage. The data underwent a two-step procedure for structural equation modeling (SEM) [79]. Firstly, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was executed to evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement model. Subsequently, SEM was conducted to examine the connections between the study variables. For these analyses, we used the SPSS 25 and AMOS 25 software packages.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

CFA assessed the measurement model’s psychometric properties. The results showed that the measurement model fitted the data well: χ2 = 577.09, χ2/df = 1.62, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.07. The reliability of the measures was evaluated by examining Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and composite reliability (CR) values (see Table 2) [80]. The results showed that the scales exhibited good reliability as Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of all constructs were more than acceptable, ranging from 0.87–0.95 [31] and, therefore, meeting the threshold requirement (>0.70). Factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) values were employed to examine the construct and convergent validity of the measures. All factor loadings of the measures showed high significance, with the smallest factor loading being 0.66. The AVE values were greater than 0.50 (ranging from 0.59–0.82), satisfying the threshold criteria. In conclusion, the measurement model exhibited sufficient psychometric properties.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and consistency coefficients for each variable.

A Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationship between the study variables (Table 2). The findings indicated significant positive correlations between WO and three variables: envy (r = 0.33; p < 0.001), job stress (r = 0.17; p < 0.01), and burnout (r = 0.21; p < 0.001). Moreover, the results of this analysis demonstrated a positive association between envy and stress (r = 0.19; p < 0.001).

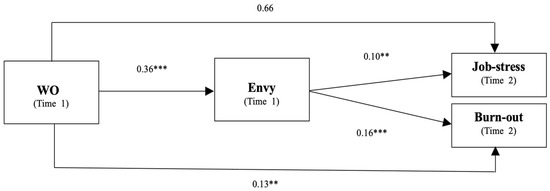

4.2. Structure Model Assessment

The model presented in this study was appropriate because all fitness indices were within reasonable bounds (see Table 3 and Figure 2). Various fitness indices were used to evaluate the model’s fit, including the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Chi-square normalized by degrees of freedom. The proposed structural model showed a reasonable fit to the data with the following values: χ2 = 584.30, χ2/df = 1.63, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.07 [81]. Table 4 presents the results of the standardized path coefficients for all hypothesized relationships between the variables.

Table 3.

Results of the hypothesized model.

Figure 2.

The research model with path coefficients. Note: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Results of bootstrapped indirect effect tests.

Moreover, WO had an indirect positive effect (β = 0.03, 0.06, p < 0.01) on negative health outcomes (job stress and burnout) mediated by envy, with an acceptable range of 95% CI. Since this CI did not contain 0, we concluded that envy significantly mediated the relationship between WO and negative health outcomes (job stress and burnout). The direct positive effect of WO on burnout was 0.14 (p < 0.01); therefore, the mediating effect of envy was partial. The total effect of WO on negative health outcomes, that is, job stress and burnout, was 0.10 and 0.19, respectively.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our study showed that employees who recognized WO within their organization were affected by job stress and burnout. Furthermore, employees’ self-protective perceptions of being the object of envy had a mediating effect on their WO. To achieve our research purpose, we conducted empirical research with 403 people in various companies. The results are summarized below.

First, it has been demonstrated that WO has a negative effect on health [46], job stress [82], and burnout among employees [83]. In line with the results of previous studies, we reconfirmed that WO is positively related to job stress and burnout in terms of employees’ health. As suggested by Sharma and Dhar [84], the fact that more research is needed to uncover the dangers of ostracism and the negative influence of WO, which needs to be managed more paradoxically, was also meaningfully reconfirmed by our findings.

Previous research has confirmed that job stress or burnout mediates the effect of WO on employees’ behavior and attitudes in various organizations. This study went a step further by revealing the mediating effect of perceiving envy to defend oneself. WO is a threatening situation for employees that can trigger the self-protective perception that they are the object of envy. Therefore, our study has important theoretical significance because it is the first to demonstrate the mediating effect of envy among employees in the Republic of Korea, where WO causes many social problems.

5.2. Practical Implications

In addition to its theoretical significance, this study offers the following practical implications. The study’s results confirmed that the perception of being the object of others’ envy was mediated to maintain a positive self-image in WO. However, despite this process, WO has a detrimental effect on employees’ health in an organization. It is important for leaders at the organizational level to recognize WO as a factor that needs to be managed and seek various action plans to this end. The following actions are suggested.

First, the health and psychological state of employees at the organizational level must not be neglected. Outcome variables, such as job stress and burnout, have been shown to affect performance through various previous studies. Therefore, checking employees’ health and psychological status in the organization on an annual or quarterly basis and ascertaining the frequency of experiences similar to WO is the most reliable way to confirm the impact of WO, which is not easily revealed.

Second, if WO is managed within the organization in terms of human resource development, cooperative and mutually beneficial behaviors among employees can be promoted by conducting group discussions or training that boost these behaviors. As part of this process, it is recommended to conduct training on how to use appropriate body language and multiple perspectives on communication [3]. In developing an organizational training program, a plan that can eliminate negative emotions or relationships should be sought. Through the implementation of such a program, employees can assist each other to cooperate constructively.

Those who instigate WO must be held accountable irrespective of their hierarchical reputation or unique talent. Additionally, providing stress relief options, such as a company fitness center, human resources hotline, or a conflict mediator, can encourage employees to develop a means to vent their pent-up emotions without passing them on to other employees. WO seems to be spreading due to competition between individuals as competition between companies intensifies due to technological advancement. This quiet but aggressive action requires more academic focus. We hope this study will contribute to sustainable organizations by triggering awareness of the negative interactions caused by WO.

6. Limitations and Strengths

As with all research, some limitations in our study should be considered. First, it is important to confirm the mediating effect of the recognition of envy in the impact of WO on health-related job stress and burnout among employees. However, attempting to maintain a positive self-image in a difficult environment within an organization can be an effort to survive. In this study, only the negative effects of WO were examined; however, as Balliet and Ferris [10] asserted, ostracism may also have the positive effect of promoting prosocial behaviors, for example, organizational citizenship behaviors, depending on the situation within the organization. Therefore, future research needs to confirm whether WO leads to both negative effects and altruistic behaviors, such as organizational citizenship behaviors, that are beneficial to organizations. Efforts in this direction will enable us to undertake new evaluations of the perception of envy that occurs in threatening situations within organizations. Second, in designing this WO study, a common method bias error was implied by using a questionnaire from the same respondent for all variables. To counter this limitation, a cross-sectional design was adopted, using the data collected by setting two different time points for questionnaire collection. Nevertheless, more sophisticated results could be obtained if the dependent variable is measured using more objective health-related third-party data. Third, this study targeted only office workers in Korea, and our findings should be verified in other countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, E.J.; Methodology, Formal Analysis, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by research funding from Honam University in 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Honam Univerisity (1041223-202202-HR-23).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results are available from the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferris, D.L.; Brown, D.J.; Berry, J.W.; Lian, H. The development and validation of the Workplace Ostracism Scale. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1348–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlan, R.T.; Cliffton, R.J.; DeSoto, M.C. Perceived exclusion in the workplace: The moderating effects of gender on work-related attitudes and psychological health. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2006, 8, 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, E.; Chen, X. How can we make a sustainable workplace? Workplace ostracism, employees’ well-being via need satisfaction and moderated mediation role of authentic leadership. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.L.; Tams, S.; Schippers, M.C.; Lee, K. Opening the black box: Why and when workplace exclusion affects social reconnection behaviour, health, and attitudes. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamian-Wilk, M.; Madeja-Bien, K. Ostracism in the workplace. In Special Topics and Particular Occupations, Professions and Sectors; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hitlan, R.T.; Kelly, K.M.; Schepman, S.; Schneider, K.T.; Zárate, M.A. Language exclusion and the consequences of perceived ostracism in the workplace. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2006, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Stallworth, L.E. Racial/ethnic bullying: Exploring links between bullying and racism in the US workplace. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D.; Zadro, L. Ostracism: On being ignored, excluded, and rejected. In Interpersonal Rejection; Leary, M.R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Korea’s Increase in Suicides and Psychiatric Bed Numbers is Worrying; OECD: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Balliet, D.; Ferris, D.L. Ostracism and prosocial behavior: A social dilemma perspective. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 120, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWall, C.N.; Twenge, J.M.; Gitter, S.A.; Baumeister, R.F. It’s the thought that counts: The role of hostile cognition in shaping aggressive responses to social exclusion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. Social comparison theory. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, S.R.; Tesser, A. Self-evaluation maintenance and evolution: Some speculative notes. In Handbook of Social Comparison: Theory and Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Vohs, K.D. Interpersonal evaluations following threats to self: Role of self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Tambor, E.S.; Terdal, S.K.; Downs, D.L. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.T.; Pinel, E.C.; Wilson, T.D.; Blumberg, S.J.; Wheatley, T.P. Immune neglect: A source of durability bias in affective forecasting. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E. Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. Am. Psychol. 1983, 38, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesser, A. Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 21, 181–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.K.; Shaw, J.D.; Schaubroeck, J.M. Envy in organizational life. Envy Theory Res. 2008, 2, 167–189. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, M.K.; Shaw, J.D.; Scott, K.L.; Tepper, B.J. The moderating roles of self-esteem and neuroticism in the relationship between group and individual undermining behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfooz, Z.; Arshad, A.; Nisar, Q.A.; Ikram, M.; Azeem, M. Does workplace incivility & workplace ostracism influence the employees’ turnover intentions? Mediating role of burnout and job stress & moderating role of psychological capital. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Abdullah, M.I.; Hafeez, H.; Chughtai, M.A. How does workplace ostracism lead to service sabotage behavior in nurses: A conservation of resources perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.W. Workplace ostracism and workplace behaviors: A moderated mediation model of perceived stress and psychological empowerment. Anxiety Stress Coping 2018, 31, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Ming, X.; Siddiqi, A.F.; Rasool, S.F. An empirical study analyzing job productivity in toxic workplace environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 24, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradfield, M.; Aquino, K. The effects of blame attributions and offender likableness on forgiveness and revenge in the workplace. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 607–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, W.G.; Smith, R.H. Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 906–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.P. Negative emotion in the workplace: Employee jealousy and envy. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2000, 7, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of Individuals′FIT at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers; Cartwright, D., Ed.; Harper & Brothers: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann, E.L.; Cohen, G.L. “I think it, therefore it’s true”: Effects of self-perceived objectivity on hiring discrimination. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 104, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, L.J.; Skarlicki, D.P.; Pugh, S.D. Exploring the role of emotions in injustice perceptions and retaliation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, C.D. Emotional and behavioral reactions to social undermining: A closer look at perceived offender motives. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 108, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S. Counterproductive work behavior and organisational citizenship behavior: Are they opposite forms of active behavior? Appl. Psychol. 2010, 59, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Schabram, K. Invisible at work: Workplace ostracism as aggression. In Research and Theory on Workplace Aggression; Bowling, N.A., Hershcovis, M.S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 221–244. [Google Scholar]

- Vardi, Y.; Wiener, Y. Misbehavior in organizations: A motivational framework. Org. Sci. 1996, 7, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, R.A.; Greenberg, J. Antisocial Behavior in Organizations; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, J.H.; Baron, R.A. Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence concerning specific forms, potential causes, and preferred targets. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.W.; O’Leary-Kelly, A.E.; Collins, J.M. Dysfunctional Behavior in Organizations: Violent and Deviant Behavior; Elsevier Science/JAI Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.J.; Robinson, S.L. Development of a measure of workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackett, P.; DeVore, C. Counterproductive behaviors at work: In Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology; Anderson, N., Ones, D.S., Sinangil, H.K., Viswesvaran, C., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 1, pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, M.K.; Ganster, D.C.; Pagon, M. Social undermining in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, D. Prevalence and forms of bullying among business professionals: A comparison of two different strategies for measuring bullying. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.L.; O’Reilly, J.; Wang, W. Invisible at work: An integrated model of workplace ostracism. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, J.; Robinson, S.L.; Berdahl, J.L.; Banki, S. Is negative attention better than no attention? The comparative effects of ostracism and harassment at work. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 774–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Peeters, M.C. Job stress and burnout among correctional officers: A literature review. J. Stress Manag. 2000, 7, 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jahanzeb, S.; Fatima, T. The role of defensive and prosocial silence between workplace ostracism and emotional exhaustion. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc. 2017, 2017, 17107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovides, A.; Fountoulakis, K.N.; Kaprinis, S.; Kaprinis, G. The relationship between job stress, burnout and clinical depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2003, 75, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff burn-out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.D. Social Ostracism Aversive Interpersonal Behaviors; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 133, p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Doef, M.; Maes, S. The job demand-control (-support) model and psychological well-being: A review of 20 years of empirical research. Work Stress 1999, 13, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, M. Analyzing and Theorizing the Dynamics of the Workplace Incivility Crisis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Rupp, D.E.; Byrne, Z.S. The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Bowler, W.M. Organizational citizenship behaviors and burnout. In Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Review of ‘Good Soldier’Activity in Organizations; Turnipseed, D.L., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaphy, E.D.; Dutton, J.E. Positive social interactions and the human body at work: Linking organizations and physiology. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Z.; Yim, F.H.k.; Kwan, H.K.; Zhang, X. Coping with workplace ostracism: The roles of ingratiation and political skill in employee psychological distress. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Charash, Y. Episodic envy. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 2128–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalin, L.J. On the problem of envy: Social, clinical and theoretical considerations. Scand. Psychoanal. Rev. 1979, 2, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, J.J.; Lobel, M. The perils of outperformance: Sensitivity about being the target of a threatening upward comparison. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 307–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, T.; Thompson, L. Don’t hate me because I’m beautiful: Self-enhancing biases in threat appraisal. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 104, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, S.R.; Tesser, A. Self-esteem and the extended self-evaluation maintenance model: The self in social context. In Efficacy, Agency, and Self-Esteem; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 145–170. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Smart, L.; Boden, J.M. Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem. Psychol. Rev. 1996, 103, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Richman, L.; Leary, M.R. Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: A multimotive model. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 116, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadro, L.; Williams, K.D.; Richardson, R. Riding the ‘O’train: Comparing the effects of ostracism and verbal dispute on targets and sources. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2005, 8, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, K.; Narayanan, J.; McAllister, D.J. Envy as pain: Rethinking the nature of envy and its implications for employees and organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology; Methodology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, R.T. The role of performance and absenteeism in the prediction of turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliath, T.J.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Gillespie, D.F.; Bluedorn, A.C. A test of the Maslach Burnout Inventory in three samples of healthcare professionals. Work Stress 2000, 14, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Methods, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Abdullah, M.I.; Sarfraz, M.; Imran, M.K. Collaborative effect of workplace ostracism and self-efficacy versus job stress. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2019, 15, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Yang, F.; Wang, B.; Huang, C.; Song, B. When workplace ostracism leads to burnout: The roles of job self-determination and future time orientation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 2465–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Dhar, R.L. From curse to cure of workplace ostracism: A systematic review and future research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2022, 32, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).