Educating Youth to Civic Engagement for Social Justice: Evaluation of a Secondary School Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Civic Engagement between Social and Individual Dimensions

1.2. Education for Civic Engagement

1.3. The Project

1.4. The Current Study: Objectives and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics at T1

3.2. T-Tests and Correlations

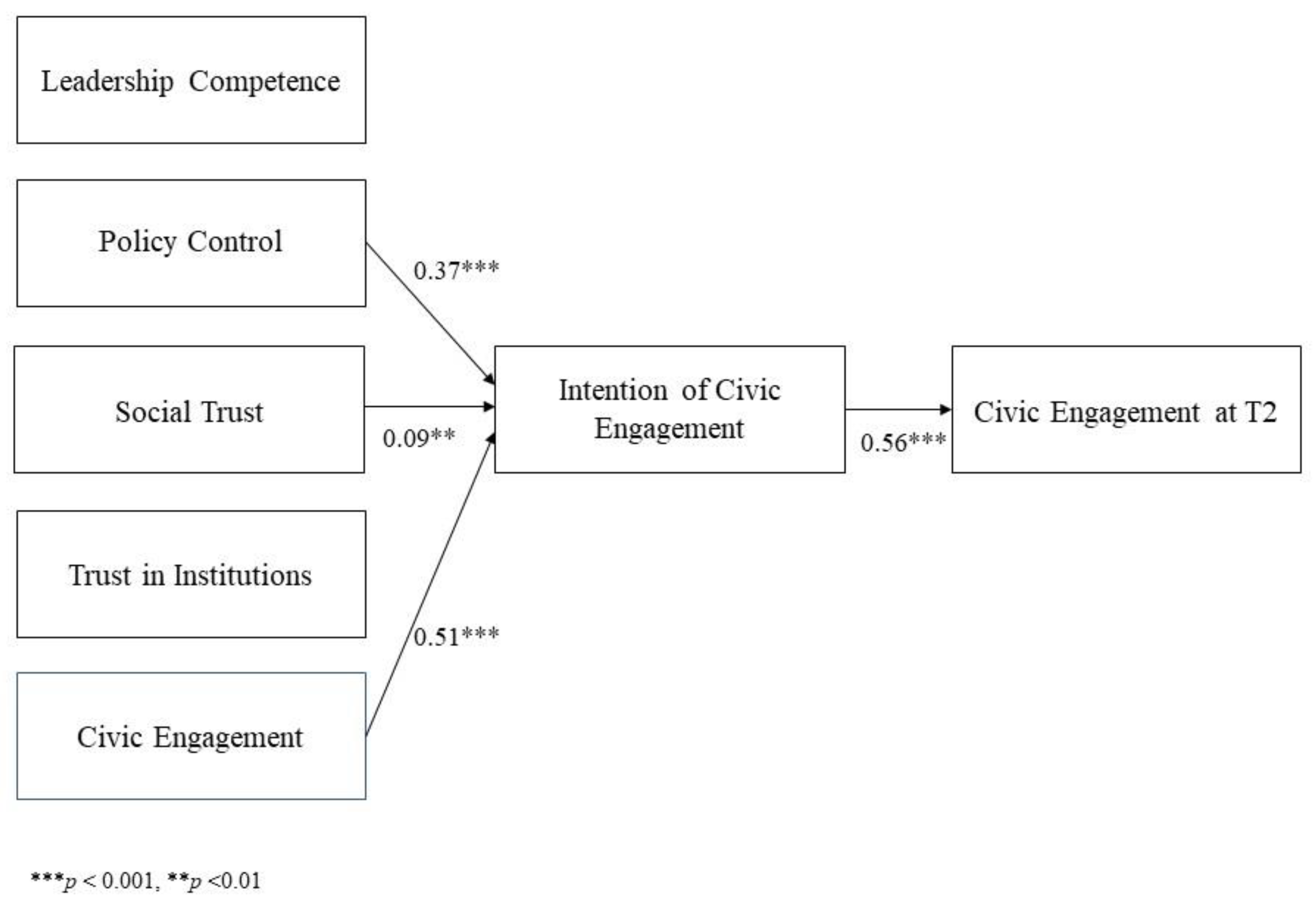

3.3. Path Analysis to Test the Hypothesised Model

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, R.P.; Goggin, J. What Do We Mean by “Civic Engagement”? J. Transform. Educ. 2005, 3, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanesi, C.; Cicognani, E.; Zani, B. Sense of community, civic engagement and social well-being in Italian adolescents. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 17, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.Y.; Ou, S.R.; Reynolds, A.J. Adolescent Civic Engagement and Adult Outcomes: An Examination among Urban Racial Minorities. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1829–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaff, J.; Boyd, M.; Li, Y.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. Active and Engaged Citizenship: Multi-group and Longitudinal Factorial Analysis of an Integrated Construct of Civic Engagement. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 736–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaff, J.F.; Kawashima-Ginsberg, K.; Lin, E.S.; Lamb, M.; Balsano, A.; Lerner, R.M. Developmental trajectories of civic engagement across adolescence: Disaggregation of an integrated construct. Individual and contextual bases of Thriving in adolescence: Findings from the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsano, A.B. Youth Civic Engagement in the United States: Understanding and Addressing the Impact of Social Impediments on Positive Youth and Community Development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2005, 9, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M.; Vieno, A.; Pastore, M.; Santinello, M. Neighborhood social connectedness and adolescent civic engagement: An integrative model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denault, A.S.; Poulin, F.; Pedersen, S. Intensity of Participation in Organized Youth Activities during the High School Years: Longitudinal Associations with Adjustment. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2009, 13, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.M.; Larson, R.W.; Dworkin, J.B. What Adolescents Learn in Organized Youth Activities: A Survey of Self-Reported Developmental Experiences. J. Res. Adolesc. 2003, 13, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieno, A.; Nation, M.; Perkins, D.D.; Santinello, M. Civic participation and the development of adolescent behavior problems. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 35, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M.; Vieno, A.; Perkins, D.D.; Santinello, M.; Elgar, F.J.; Morgan, A.; Mazzardis, S. Family Affluence, School and Neighborhood Contexts and Adolescents’ Civic Engagement: A Cross-National Study. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 50, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obradović, J.; Masten, A.S. Developmental Antecedents of Young Adult Civic Engagement. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2007, 11, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Lenzi, M.; Sharkey, J.D.; Vieno, A.; Santinello, M. Factors Associated with Civic Engagement in Adolescence: The Effects of Neighborhood, School, Family, and Peer Contexts. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 44, 1040–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishishiba, M.; Nelson, H.T.; Shinn, C.W. Explicating Factors That Foster Civic Engagement among Students. J. Public Aff. Educ. 2005, 11, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.S.; Hope, E.C.; Eisman, A.B.; Zimmerman, M.A. Predictors of Civic Engagement among Highly Involved Young Adults: Exploring the Relationship between Agency and Systems Worldview. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 44, 888–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, A.; Bilewicz, M.; Lewicka, M. The merits of teaching local history: Increased place attachment enhances civic engagement and social trust. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Touchstone Books/Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torney-Purta, J.; Richardson, W.K.; Barber, C.H. Trust in Government-Related Institutions and Civic Engagement among Adolescents: Analysis of Five Countries from the IEA Civic Education Study; CIRCLE Working Paper 17; Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement: College Park, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, E.C.; Jagers, R.J. The Role of Sociopolitical Attitudes and Civic Education in the Civic Engagement of Black Youth. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardier, D.T.; Opara, I.; Garcia-Reid, P.; Reid, R.J. The Mediating Role of Ethnic Identity and Social Justice Orientation between Community Civic Participation, Psychological Sense of Community, and Dimensions of Psychological Empowerment among Adolescents of Color. Urban. Rev. 2021, 53, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, K.G.; Peterson, N.A.; Treitler, P.C.; Lardier, D.T., Jr.; Rashid, M.; Reid, R.J. Measuring Youth Empowerment: An Item Response Theory Analysis of the Sociopolitical Control Scale for Youth. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 68, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieno, A.; Lenzi, M.; Canale, N.; Santinello, M. Italian Validation of The Sociopolitical Control Scale for Youth (SPCS-Y). J. Community Psychol. 2014, 42, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R.J.; Williams, N.C.; Jagers, R.J. Sociopolitical Development. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 31, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Zahniser, J.H. Refinements of sphere-specific measures of perceived control: Development of a sociopolitical control scale. J. Community Psychol. 1991, 19, 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, J.; Durrheim, K.; Kerr, P.; Thomae, M. What’s So Funny «Bout Peace, Love and Understanding?» Further Reflections on the Limits of Prejudice Reduction as a Model of Social Change. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 2013, 1, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.C.; Baray, G. Models of social change in social psychology: Collective action or prejudice reduction? Conflict or harmony? In Beyond Prejudice: Extending the Social Psychology of Conflict, Inequality and Social Change; Dixon, J., Keynes, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 225–247. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, N.K.; Becker, J.C.; Benz, A.; Christ, O.; Dhont, K.; Klocke, U.; Neji, S.; Rychlowska, M.; Schmid, K.; Hewstone, M. Intergroup contact and social change: Implications of negative and positive contact for collective action in advantaged and disadvantaged groups. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathi, S.; Cameron, L.; Hartley, B.; Bradford, S. Imagined contact as a prejudice-reduction intervention in schools: The underlying role of similarity and attitudes. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Commentary: South African Contributions to the Study of Intergroup Relations. J. Soc. Issues 2010, 66, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakal, H.; Halabi, S.; Cazan, A.M.; Eller, A. Intergroup contact and endorsement of social change motivations: The mediating role of intergroup trust, perspective-taking, and intergroup anxiety among three advantaged groups in Northern Cyprus, Romania, and Israel. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2021, 24, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zomeren, M.; Spears, R.; Leach, C.W. Exploring psychological mechanisms of collective action: Does relevance of group identity influence how people cope with collective disadvantage? Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zomeren, M.; Postmes, T.; Spears, R. Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 504–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zomeren, M.; Leach, C.W.; Spears, R. Protesters as “Passionate Economists”: A dynamic dual pathway model of approach coping with collective disadvantage. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanesi, C.; Mazzoni, D.; Cicognani, E.; Zani, B. Discriminatory Contexts, Emotions and Civic/Political Engagement among Native Italians and Migrants. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 26, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, Y.G.; Uluğ, Ö.M. Examining Prejudice Reduction Through Solidarity and Togetherness Experiences Among Gezi Park Activists in Turkey. J. Soc. Political Psychol. 2016, 4, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, T.; Fedi, A. Ingiustizia e diseguaglianze sociali. In Psicologia Sociale del Pregiudizio; Brambilla, M., Sacco, S., Eds.; Raffaello Cortina Editore: Milan, Italy, 2022; pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Stallworth, L.M.; Malle, B.F. Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Pratto, F.; Zeineddine, F.; Sweetman, J.; Aiello, A.; Petrović, N.; Rubini, M. From Social Dominance Orientation to Political Engagement: The Role of Group Status and Shared Beliefs in Politics across Multiple Contexts. Politic Psychol. 2022, 43, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.C.; Pratto, F.; Johnson, B.T. Intergroup consensus/disagreement in support of group-based hierarchy: An examination of socio-structural and psycho-cultural factors. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 1029–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.F.; McGarty, C.; Reese, G.; Berndsen, M.; Bliuc, A.M. Where there is a (collective) will, there are (effective) ways: Integrating individual-and group-level factors in explaining humanitarian collective action. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 42, 1678–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bynner, J.; Schuller, T.; Feinstein, L. Wider benefits of education: Skills, higher education and civic engagement. Z. Für Pädagogik 2003, 49, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, M.; Cole, D. Disentangling the impact of diversity courses: Examining the influence of diversity course content on students’ civic engagement. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2015, 56, 794–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisby, B.; Sloam, J. Promoting youth participation in democracy: The role of higher education. In Beyond the Youth Citizenship Commission: Young People and Politics; Political Studies Association, Mycock, A., Tonge, J., Eds.; Political Studies Association: London, UK, 2014; pp. 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, N.; Edwards, K. Does civic education for young people increase political participation? A systematic review. Educ. Rev. 2014, 66, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, A.I.; Henn, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pontes, H.M. Validation of the Online Political Engagement Scale in a British population survey. Aloma Rev. Psicol. Ciènc. L’educació I L’esport 2017, 35, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahen, J.E.; Sporte, S.E. Developing citizens: The impact of civic learning opportunities on students’ commitment to civic participation. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 45, 738–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie Corporation of New York and CIRCLE. The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (2003). In The Civic Mission of Schools; Carnegie Corporation: New York, NY, USA; Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Youniss, J. Civic Education: What Schools Can Do to Encourage Civic Identity and Action. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2011, 15, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasek, J.; Feldman, L.; Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Schools as Incubators of Democratic Participation: Building Long-Term Political Efficacy with Civic Education. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2008, 12, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P.; Fiske, S.T. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, C.; Glick, P.; Tartaglia, S. Psychometric properties of short versions of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory and Ambivalence Toward Men Inventory. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 21, 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- European Social Survey (ESS). Round 7 Module on Attitudes towards Immigration and Their Antecedents—Question Design Final Module in Template; Centre for Comparative Social Surveys, City University London: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akrami, N.; Ekehammar, B.; Araya, T. Classical and modern racial prejudice: A study of attitudes toward immigrants in Sweden. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 521–532. [Google Scholar]

- Gattino, S.; Miglietta, A.; Testa, S. The Akrami, Ekehammar and Araya’s Classical and Modern Racial Prejudice Scale in the Italian context. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 18, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano, G.; Roccato, M. Una banca dati per misurare l’orientamento alla dominanza sociale in Italia. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 12, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbio, A.; Fochesato, M.; Manganelli, A.N.; Crivellari, F. La scala di controllo sociopolitico di Zimmerman e Zahniser (SPCS, 1991). Un contributo all’adattamento italiano con metodo carta e matita e Web-based. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 12, 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wray-Lake, L.; Flanagan, C.A. Parenting practices and the development of adolescents’ social trust. Political Civ. Engagem. Dev. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzana, D.; Marta, E.; Pozzi, M. Young Adults and Civic Behavior: The Psychosocial Variables Determining It. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2012, 40, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.D.; Azevedo, C.N.; Menezes, I. The developmental quality of participation experiences: Beyond the rhetoric that “participation is always good!”. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthen, M.G.; Lingiardi, V.; Caristo, C. The roles of politics, feminism, and religion in attitudes toward LGBT individuals: A cross-cultural study of college students in the USA, Italy, and Spain. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2017, 14, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjogren, A.L.; Bae, C.L.; Deutsch, N.L.; Zumbrunn, S.; Broda, M. Afterschool engagement: A mixed methods approach to understanding profiles of youth engagement. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2022, 26, 638–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, M.K.; Gellermann, J.M.; Holtmann, E.; Jaeck, T.; Körner, A.; Silbereisen, R.K. Applying the volunteer process model to predict future intentions for civic and political participation: Same antecedents, different experiences? J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 162, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.P.; Pancer, M.S. Community service experiences and commitment to volunteering. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 320–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A.; Suárez-Orozco, M.; Ben-Peretz, M. Global Migration, Diversity, and Civic Education: Improving Policy and Practice; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, D.C.; Braganza, S.U.; Delos Reyes, B.D. Youth Civic Engagement in the Philippines: The Association between Social Dominance Orientation and Civic Engagement through Locus of Control. Bachelor’s Thesis, De la Salle University, Manila, Philippines, 2012. Available online: https://animorepository.dlsu.edu.ph/etd_bachelors/10846 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Martini, M.; Fedi, A.; Resceanu, A.; Tilea, M. Engaging young Mindchangers in climate action: A case study of two European regions. Psicol. Comunità 2023, 1, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min–Max | Time 1 | Time 2 | t | |

| Hostile Sexism | 0–5 | 1.44 (1.08) | 1.18 (1.08) | 4.21 *** |

| Benevolent Sexism | 0–5 | 2.09 (1.18) | 1.88 (1.17) | 3.43 *** |

| LGBT Prejudice | 1–5 1 | 4.70 (0.58) | 4.73 (0.56) | −1.03 |

| Classical Ethnic Prejudice | 1–5 | 2.01 (0.59) | 1.91 (0.59) | 2.47 * |

| Modern Ethnic Prejudice | 1–5 | 2.15 (0.63) | 1.99 (0.60) | 3.80 *** |

| Social Dominance Orientation | 0–4 | 1.73 (0.67) | 1.60 (0.61) | 3.01 ** |

| Leadership Competence | 1–4 | 2.80 (0.55) | 2.83 (0.54) | −0.92 |

| Policy Control | 1–4 | 2.66 (0.46) | 2.63 (0.48) | 0.94 |

| Social Trust | 1–5 | 2.99 (0.81) | 3.03 (0.90) | −0.52 |

| Trust in Institutions | 1–5 | 2.29 (0.43) | 2.41 (0.42) | −3.48 *** |

| Civic Engagement | 1–5 | 2.79 (0.72) | 2.81 (0.68) | −0.31 |

| Intention of Civic Engagement | 1–5 | 2.88 (0.64) | 2.93 (0.66) | −0.90 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Civic Engagement T1 | ||||||

| 2. Civic Engagement T2 | 0.52 ** | |||||

| 3. Leadership Competence T1 | 0.15 ** | 0.05 | ||||

| 4. Policy Control T1 | 0.36 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.28 ** | |||

| 5. Social Trust T1 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.08 | ||

| 6. Trust in Institutions T1 | 0.10 * | 0.04 | 0.12 * | 0.21 ** | 0.24 ** | |

| 7. Intention of Civic Engagement T1 | 0.67 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.19 ** |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Civic Engagement T1 | |||||||

| 2. Civic Engagement T2 | 0.52 ** | ||||||

| 3. Hostile Sexism T2 | −0.05 | 0.04 | |||||

| 4. Benevolent Sexism T2 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.50 ** | ||||

| 5. LGBT Prejudice T2 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.37 ** | 0.34 ** | |||

| 6. Classical Ethnic Prejudice T2 | −0.17 | −0.11 | 0.47 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.46 ** | ||

| 7. Modern Ethnic Prejudice T2 | −0.11 | −0.18 | 0.49 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.57 ** | |

| 8. Social Dominance Orient. T2 | −0.15 | −0.15 | 0.52 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.70 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martini, M.; Rollero, C.; Rizzo, M.; Di Carlo, S.; De Piccoli, N.; Fedi, A. Educating Youth to Civic Engagement for Social Justice: Evaluation of a Secondary School Project. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080650

Martini M, Rollero C, Rizzo M, Di Carlo S, De Piccoli N, Fedi A. Educating Youth to Civic Engagement for Social Justice: Evaluation of a Secondary School Project. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):650. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080650

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartini, Mara, Chiara Rollero, Marco Rizzo, Sabrina Di Carlo, Norma De Piccoli, and Angela Fedi. 2023. "Educating Youth to Civic Engagement for Social Justice: Evaluation of a Secondary School Project" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080650

APA StyleMartini, M., Rollero, C., Rizzo, M., Di Carlo, S., De Piccoli, N., & Fedi, A. (2023). Educating Youth to Civic Engagement for Social Justice: Evaluation of a Secondary School Project. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080650