Differences in Aggressive Behavior of Individuals with Different Self-Construal Types after Social Exclusion in the Same Cultural Background

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Effects of Social Exclusion on Individual Behavioral Responses

1.2. Effects of Self-Construal on Individual Behavioral Responses

1.3. The Present Study and Hypotheses

2. Experiment 1: Differences in Relational Aggression of Individuals with Different Self-Construal Types after Being Excluded

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Design

2.1.3. Materials

2.1.4. Procedures

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Manipulation Check

2.2.2. Examination of Differences in the Influence of Social Exclusion on Relational Aggression in Different Self-Constructors

3. Experiment 2: Differences in Physical Aggression of Individuals with Different Self-Construal Types after Being Excluded

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Design

3.1.3. Materials

3.1.4. Procedures

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Manipulation Check

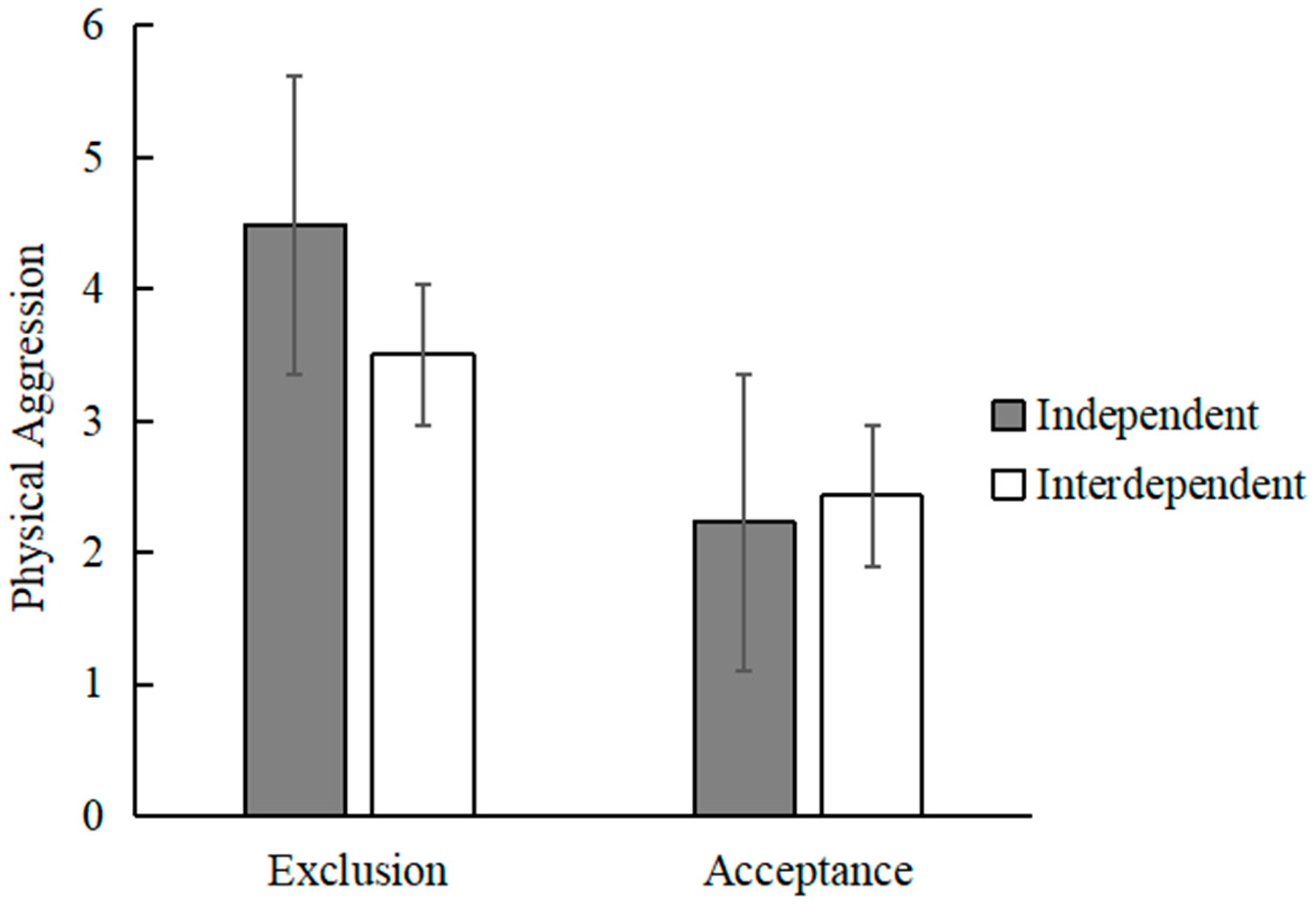

3.2.2. Examination of Differences in the Influence of Social Exclusion on Physical Aggression in Different Self-Constructors

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in the Types of Individual Self-Construal in the Same Cultural Background

4.2. Differences in Aggressive Behavior among Different Self-Constructors after Being Excluded

4.3. Differences in Relational Aggression and Physical Aggression among Different Self-Constructors after Being Excluded

4.4. Implications and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zych, I.; Ttofi, M.M.; Llorent, V.J.; Farrington, D.P.; Ribeaud, D.; Eisner, M.P. A longitudinal study on stability and transitions among bullying roles. Child Dev. 2020, 91, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muarifah, A.; Mashar, R.; Hashim, I.H.M.; Rofiah, N.H.; Oktaviani, F. Aggression in adolescents: The role of mother-child attachment and self-esteem. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, J. Aggression, aggression-related psychopathologies and their models. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 936105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, M.R.; Kowalski, R.M.; Smith, L.; Phillips, S. Teasing, rejection, and violence: Case studies of the school shootings. Aggress. Behav. 2003, 29, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Twenge, J.M.; Quinlivan, E. Interpersonal rejection as a determinant of anger and aggression. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter-Scheidl, K.; Papousek, I.; Lackner, H.K.; Paechter, M.; Weiss, E.M.; Aydin, N. Aggressive behavior after social exclusion is linked with the spontaneous initiation of more action-oriented coping immediately following the exclusion episode. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 195, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, W.A.; Williams, K.D.; Cairns, D.R. When ostracism leads to aggression: The moderating effects of control deprivation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 42, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojuharenco, I.; Shteynberg, G.; Gelfand, M.; Schminke, M. Self-construal and unethical behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wei, M. Differences in automatic emotion regulation after social exclusion in individuals with different attachment types. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2022, 185, 111296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, D.S.; DeWall, C.N. Combating the sting of rejection with the pleasure of revenge: A new look at how emotion shapes aggression. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 112, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-Y. Negative emotion and purchase behavior following social exclusion. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. 2017, 27, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijhof, C.I.; Van, D.; Overgaauw, S.; Lelieveld, G.J.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; Ijzendoorn, M.V. The prosocial cyberball game: Compensating for social exclusion and its associations with empathic concern and bullying in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2016, 52, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, E.; Tabernero, C.; Steinel, W. Motivational determinants of prosocial behavior: What do included, hopeful excluded, and hopeless excluded individuals need to behave prosocially? Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarmley, M.; Feldman, J.; Grossman, H.; Clarkson, T.; Moyer, A.; Jarcho, J.M. Testing effects of social rejection on aggressive and prosocial behavior: A meta-analysis. Aggress. Behav. 2022, 48, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masui, K.; Fujiwara, H.; Ura, M. Social exclusion mediates the relationship between psychopathy and aggressive humor style in noninstitutionalized young adults. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2013, 55, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Zee, S.; Anderson, R.; Poppe, R. When lying feels the right thing to do. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, K.E.; Winkel, R.E.; Leary, M.R. Reactions to acceptance and rejection: Effects of level and sequence of relational evaluation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 40, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajchert, J.; Konopka, K.; Boguszewski, P. Aggression and helping as responses to same-sex and opposite-sex rejection in men and women. Evol. Psychol. 2018, 16, 1474704918775253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Baumeister, R.F.; Tice, D.M.; Stucke, T.S. If you can’t join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovett, F. Rational choice theory and explanation. Ration. Soc. 2006, 18, 237–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Poon, K.-T.; DeWall, C.N. When do socially accepted people feel ostracized? Physical pain triggers social pain. Soc. Influ. 2015, 10, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseng, F.; Belsky, J.; Skalicka, V.; Wichstrøm, L. Social exclusion predicts impaired self-regulation: A 2-year longitudinal panel study including the transition from preschool to school. J. Pers. 2015, 83, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, K.T.; Wong, W.Y. Turning a blind eye to potential costs: Ostracism increases aggressive tendency. Psychol. Violence 2019, 9, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, K.T.; Teng, F. Feeling unrestricted by rules: Ostracism promotes aggressive responses. Aggress. Behav. 2017, 43, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E.; Hardin, E.E.; Gercek-Swing, B. The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 15, 142–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Cultures and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F.; Mullet, E. Personality, self-esteem, and self-construal as correlates of forgivingness. Eur. J. Pers. 2004, 18, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfundmair, M.; Graupmann, V.; Frey, D.; Aydin, N. The different behavioral intentions of collectivists and individualists in response to social exclusion. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 41, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Shao, B. Early immersive culture mixing: The key to understanding cognitive and identity differences among multiculturals. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 2016, 47, 1409–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B.J.; Felmingham, K.L.; Das, P.; Whitford, T.J.; Malhi, G.S.; Battaglini, E.; Bryant, R.A. Self-construal differences in neural responses to negative social cues. Biol. Psychol. 2017, 129, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Fu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Cropley, D.H. The effects of different types of social exclusion on creative thinking: The role of self-construal. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020, 166, 110215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D.; Cheung, C.K.T.; Choi, W. Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the internet. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papousek, I.; Reiter-Scheidl, K.; Lackner, H.K.; Weiss, E.M.; Perchtold-Stefan, C.M.; Aydin, N. The impacts of the presence of an unfamiliar dog on emerging adults’ physiological and behavioral responses following social exclusion. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, R.; Tingley, D.; Cowden, J.; Frazzetto, G.; Johnson, D.D. Monoamine oxidase A gene (MAOA) predicts behavioral aggression following provocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2118–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wei, L.; Ding, T. Social Exclusion: Self-construal Moderates Attentional Bias to Social Information. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Culture and shyness in childhood and adolescence. New Ideas Psychol. 2019, 53, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Zhang, D. Behavioral Responses to Ostracism: A Perspective from the General Aggression Model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 29, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Bushman, B.J. Media violence and the general aggression model. J. Soc. Issues 2018, 74, 386–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, A.K.; Shavitt, S.; Johnson, T. What is the relation between cultural orientation and socially desirable responding. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, S.; Einat, T. Moral judgment, crime seriousness, and the relations between them: An exploratory study. Crime Delinq. 2016, 62, 470–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mittal, V. The attractiveness of enriched and impoverished options: Culture, self-construal, and regulatory focus. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Male | Female | Age | Mage | SDage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusion-Independent (n = 30) | 15 | 15 | 16–21 | 18.09 | 1.63 |

| Exclusion-Interdependent (n = 34) | 22 | 12 | 16–21 | 18.05 | 1.63 |

| Acceptance-Independent (n = 31) | 24 | 7 | 16–21 | 18.48 | 1.67 |

| Acceptance-Interdependent (n = 33) | 17 | 16 | 16–21 | 18.24 | 1.79 |

| Total (n = 128) | 78 | 50 | 16–21 | 18.37 | 1.66 |

| Exclusion (n = 64) | Acceptance (n = 64) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent (n = 30) | Interdependent (n = 34) | Independent (n = 31) | Interdependent (n = 33) | |

| Relational Aggression | 4.29 (1.09) | 3.47 (0.69) | 2.92 (0.80) | 2.70 (0.72) |

| Effect | Measure | F (1, 122) | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | relational aggression | 53.94 | <0.001 | 0.31 |

| Self-construal type | relational aggression | 9.15 | 0.003 | 0.07 |

| Group × Self-construal type | relational aggression | 5.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Male | Female | Age | Mage | SDage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusion-Independent (n = 35) | 15 | 20 | 16–20 | 17.14 | 0.88 |

| Exclusion-Interdependent (n = 36) | 21 | 15 | 16–20 | 17.44 | 1.27 |

| Acceptance-Independent (n = 35) | 27 | 8 | 15–20 | 17.60 | 1.01 |

| Acceptance-Interdependent (n = 35) | 17 | 18 | 16–20 | 17.60 | 1.24 |

| Total (n = 141) | 80 | 61 | 15–20 | 17.45 | 1.12 |

| Exclusion (n = 71) | Acceptance (n = 70) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent (n = 35) | Interdependent (n = 36) | Independent (n = 35) | Interdependent (n = 35) | |

| Physical Aggression | 4.49 (2.06) | 3.50 (1.78) | 2.23 (1.48) | 2.43 (1.07) |

| Effect | Measure | F (1, 135) | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | physical aggression | 32.74 | <0.001 | 0.17 |

| Self-construal type | physical aggression | 1.64 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| Group × Self-construal type | physical aggression | 4.23 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Zou, Y.; Yin, H.; Jiang, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F. Differences in Aggressive Behavior of Individuals with Different Self-Construal Types after Social Exclusion in the Same Cultural Background. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080623

Yang X, Zou Y, Yin H, Jiang R, Wang Y, Wang F. Differences in Aggressive Behavior of Individuals with Different Self-Construal Types after Social Exclusion in the Same Cultural Background. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(8):623. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080623

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xiaoli, Yan Zou, Hang Yin, Rui Jiang, Yuan Wang, and Fang Wang. 2023. "Differences in Aggressive Behavior of Individuals with Different Self-Construal Types after Social Exclusion in the Same Cultural Background" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 8: 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080623

APA StyleYang, X., Zou, Y., Yin, H., Jiang, R., Wang, Y., & Wang, F. (2023). Differences in Aggressive Behavior of Individuals with Different Self-Construal Types after Social Exclusion in the Same Cultural Background. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13080623