The Relationship between Parent-Offspring Communication and the School Adaptation of Leftover Children in Overseas Countries: The Mediating Role of Companionship and the Moderating Role of a Sense of Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Relationship between Parent-Offspring Communication and School Adaptation

1.2. The Mediating Role of Companionship

1.3. Moderating Effect of Safety Perception

1.4. Purpose of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measure

2.2.1. Parent-Offspring Communication Scale

2.2.2. School Adaptation Scale

2.2.3. Student Companionship Scale

2.2.4. The Sense of Safety Scale

2.3. Research Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Deviation Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Latent Variable Correlation Analysis

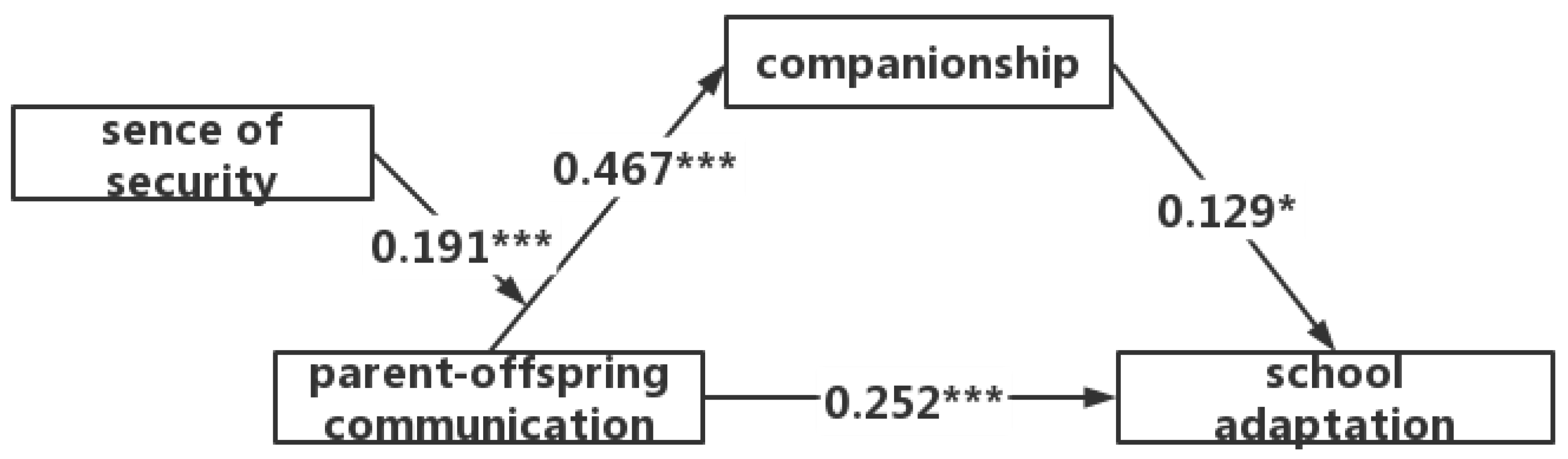

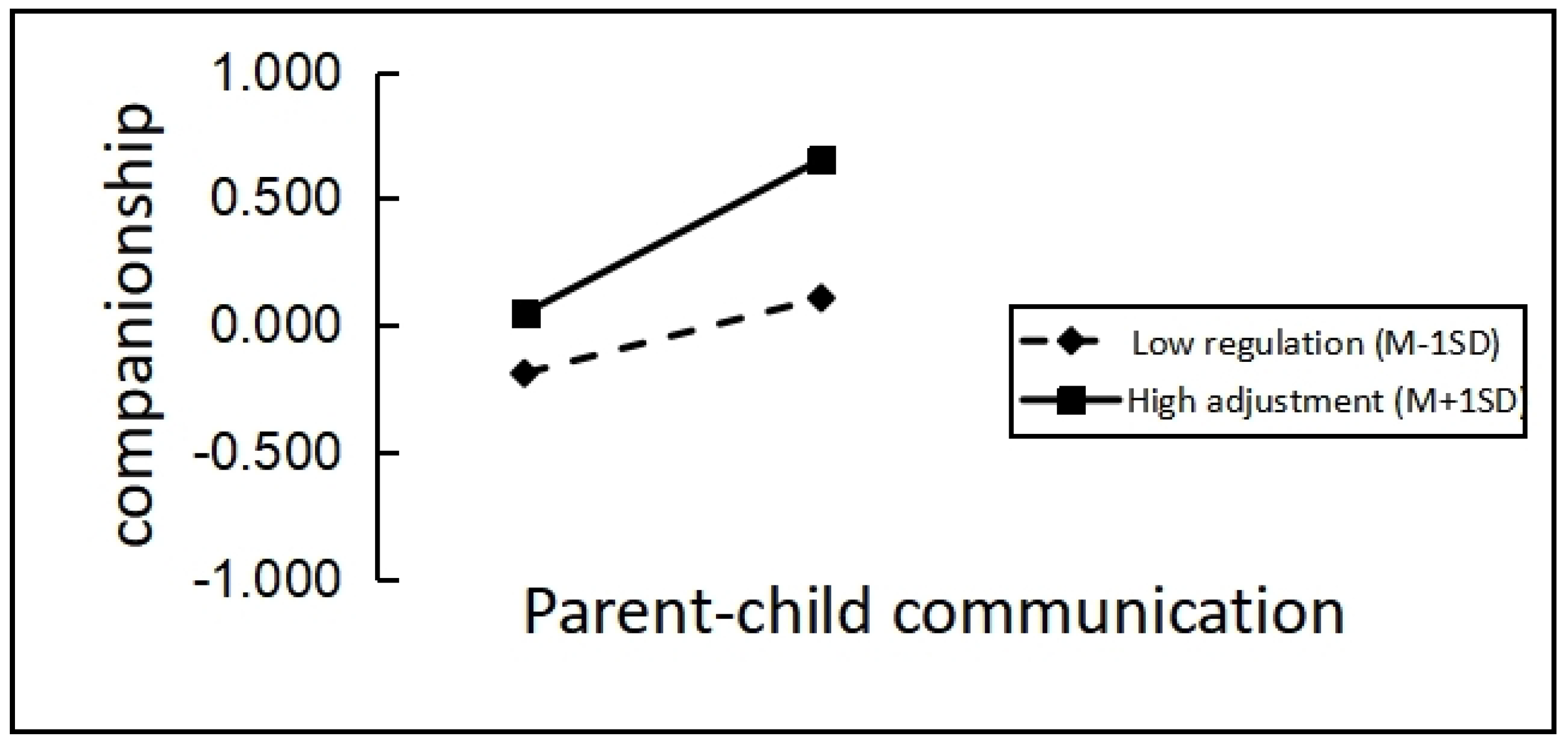

3.3. The Role of Parent-Offspring Communication on School Adaptation among Leftover Children in the Chinese Diaspora: A Moderately Mediating Effect

4. Discussion

4.1. The Predictive Role of Parent-Offspring Communication on School Adaptation

4.2. The Mediating Role of Companionship

4.3. Moderating Effect of Safety Perception

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, W.; Lin, S.; Lin, D.; Wang, H. Left-behind children’s social adjustment and relationship with parental coping with children’s negative emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, G.W.; Kochenderfer, B.J.; Coleman, C.C. Friendship quality as a predictor of young children’s early school adjustment. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.B. Social and cultural influences on school adjustment: The application of an identity-focused. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 34, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Mao, Y. The effect of boarding on campus on left-behind children’s sense of school belonging and academic achievement: Chinese evidence from propensity score matching analysis. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2018, 22, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lin, L.; Xu, M.; Li, L.; Lu, J.; Zhou, X. Mental Health among Left-Behind Children in Rural China in Relation to Parent-Child Communication. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Deng, C. The Impact of Parent–Child Attachment on School Adjustment in Left-behind Children Due to Transnational Parenting: The Mediating Role of Peer Relationships. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson-Arad, B.; Navaro-Bitton, I. Resilience among adolescents in foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 59, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Ashish, K.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H. Socio-emotional challenges and development of children left behind by migrant mothers. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 010806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Yan, X.; Deng, C. The influence of parent–child attachment on school adjustment among the left-behind children of overseas Chinese: The chain mediating role of peer relationships and hometown identity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1041805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, S.N.; Yu, S.H.; Wright, B.; Fung, J.; Saleem, F.; Lau, A.S. Resilience and Family Socialization Processes in Ethnic Minority Youth: Illuminating the Achievement-Health Paradox. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 25, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxcroft, D.R.; Howcutt, S.J.; Matley, F.; Bunce, L.T.; Davies, E.L. Testing socioeconomic status and family socialization hypotheses of alcohol use in young people: A causal mediation analysis. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullo, A.; Schulz, P.J. Parent-child Communication, Social Norms, and the Development of Cyber Aggression in Early Adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2022, 51, 1774–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Rothenberg, W.A.; Lansford, J.E.; Bornstein, M.H.; Chang, L.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Di Giunta, L.; Dodge, K.A.; Gurdal, S.; Malone, P.S.; et al. Cross-Cultural Examination of Links between Parent-Adolescent Communication and Adolescent Psychological Problems in 12 Cultural Groups. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, T.A.; Fox, K.; Zelkowitz, R.L.; Smith, D.M.Y.; Alloy, L.B.; Hooley, J.M.; Cole, D.A. Does nonsuicidal self-injury prospectively predict change in depression and self-criticism? Cogn. Ther. Res. 2019, 43, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, G.H. The Life Course and Human Developmentin. In Handbook of Child Psychology, Theoretical Models of Human Development; Lerner, R.M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Teubert, D.; Pinquart, M. The Association Between Coparenting and Child Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2010, 10, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, K.A.; Currie, C. Family structure, mother-child communication, father-child communication, and adolescent life satisfaction: A cross-sectional multilevel analysis. Health Educ. 2010, 110, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, J.M.; Booth, M.Z. Family and school influences on adolescents’ adjustment: The moderating role of youth hopefulness and aspirations for the future. J. Adolesc. 2015, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun-Sook, Y.; Hye-Yeon, S. Mediating effects of academic failure tolerance in the relationship between per-ceived parent-child communication and academic helplessness in primary school students. J. Learn. Cent. Curric. Educ. 2017, 17, 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, O.; Barbosa-Ducharne, M.; Canário, C. Do adolescents’ perceptions of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors predict academic achievement and social skills? Child Indic. Res. 2020, 13, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Lv, Q.; Yang, N.; Wang, F. Left-Behind Children, Parent-Child Communication and Psychological Resilience: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Bukowski, W.; Parker, J.G. Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups. In Handbook of Child Psychology. Social, Emotional, and Personality Development, 5th ed.; Damon, W., Nancy, E., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, H.; Steinhauer, P.; Sitarenios, G. Family Assessment Measure (FAM) and Process Model of Family Functioning. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 22, 190–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hu, N.; Yao, Z.; Peng, B. Family functioning and adolescent depression: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and peer relationships. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 962147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disiye, M.A. Influence of Parent-Adolescent Communication on Adolescent Peer Relations and Gender Implications. J. Arts Humanit. 2015, 4, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, E.-H.; Kim, G. Influence of Middle School Students’ Shyness and Interpersonal Anxiety on Smartphone Addiction: Focused on the Mediating Effect in Problematic Communication between Parent-Adolescent and Peer Relationship. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2017, 24, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, O.R.; Lee, J. Effects of Peer Relationship Skills on Alternative School Students’ School Adjustment. Korean J. Community Living Sci. 2014, 25, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.S. Influences of teacher and peer relationships on school adjustment of middle school students-Focusing on mediating effects of the sense of community. J. Reg. Stud. 2013, 21, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H.; Hirsh, E.; Stein, M.; Honigmann, I. A clinically derived test for measuring psychological security-insecurity. J. Gen. Psychol. 1945, 31, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumariu, L.E.; Madigan, S.; Giuseppone, K.R.; Abtahi, M.M.; Kerns, K.A. The Security Scale as a measure of attachment: Meta-analytic evidence of validity. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2018, 20, 600–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. The dynamics of psychological security-insecurity. In Proceedings of the Fifth Chinese National Conference of Sport Psychology, Kunming, China, 21–23 July 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bendel-Stenzel, L.C.; An, D.; Kochanska, G. Parent-child relationship and child anger proneness in infancy and attachment security at toddler age: A short-term longitudinal study of mother- and father-child dyads. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2021, 24, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendel-Stenzel, L.C.; An, D.; Kochanska, G. Infants’ attachment security and children’s self-regulation within and outside the parent-child relationship at kindergarten age: Distinct paths for children varying in anger proneness. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2022, 221, 105433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotova, Y.O.; Karapetyan, L.V. Psychological Security as the Foundation of Personal Psychological Well being. Psychol. Russ. State Art 2018, 2, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwain, N.L.; Holland, A.S.; Engle, J.M.; Wong, M.S.; Emery, H.T. Child-Mother Attachment Security and Child Characteristics as Joint Contributors to Young Children’s Coping in a Challenging Situation. Infant Child Dev. 2014, 24, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H.L.; Olson, D.H. Parent-Adolescent Communication and the Circumplex Model. Child Dev. 1985, 56, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Li, X.; Lin, D.; Xu, X.; Zhu, M. Psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: The role of parental migration and parent-child communication. Child Care Health Dev. 2012, 39, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.J.; Gong, L.; Wang, J.L. The revision of adolescent’s psychological Suzhi questionnaire. Int. J. Psychol. 2012, 47, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, A.J.; Asher, S.R. Children’s goals and strategies in response to conflicts within a friendship. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J. Measuring the Sense of Security of Children Left Behind in China. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2014, 42, 1585–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, B.S.; Freund, A.M. Parents as role models: Parental behavior affects adolescents’ plans for work involvement. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2011, 35, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Janhonen-Abruquah, H.; Darling, C.A. Parent-Child Communication, Relationship Quality, and Female Young Adult Children’s Well-Being in U.S. and Finland. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2022, 52, 648–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Quality Matters More Than Quantity: Parent–Child Communication and Adolescents’ Academic Performance. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Lin, L.; Roy, B.; Riley, C.; Wang, E.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Zhou, X. The impacts of parent-child communication on left-behind children’s mental health and suicidal ideation: A cross sectional study in Anhui. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 110, 104785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.-L.; Wang, L.-H.; Yin, X.-Q.; Hsieh, H.-F.; Rost, D.H.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Wang, J.-L. The promotive effects of peer support and active coping in relation to negative life events and depression in Chinese adolescents at boarding schools. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 40, 2251–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, U.F.; Chen, W.-W.; Zhang, J.; Liang, T. It feels good to learn where I belong: School belonging, academic emotions, and academic achievement in adolescents. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2015, 36, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.Y.; Kim, J.S. Factors Influencing Adolescents’ Self-control According to Family Structure. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 3520–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X. Peer Victimization, Maternal Control, And Adjustment Problems Among Left-Behind Adolescents From Father-Migrant/Mother Caregiver Families. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karberg, E.; Cabrera, N. Family change and co-parenting in resident couples and children’s behavioral problems. J. Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Li, X.; Ding, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Mediating roles of perceived social support and sense of security in the relationship between negative life events and life satisfaction among left-behind children: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X.; Fu, Q.; Bao, Q. Caregivers’ mind-mindedness and rural left-behind young children’s insecure attachment: The moderated mediation model of theory of mind and family status. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 124, 105472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent-offspring communication | 3.30 | 0.68 | 1 | |||

| 2. Companionship | 3.88 | 0.39 | 0.63 ** | 1 | ||

| 3. School adaptation | 3.24 | 0.78 | 0.50 * | 0.64 ** | 1 | |

| 4. Sense of safety | 2.75 | 0.58 | 0.49 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.24 *** | 1 |

| Safety | Effect Value | Boot Standard Error | Boot CI Lower Limit | Boot CI Higher Limit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct role | M − 1SD | 0.161 | 0.030 | 0.022 | 0.138 |

| M | 0.252 | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.110 | |

| M + 1SD | 0.284 | 0.020 | 0.012 | 0.090 | |

| The mediating role of companionship | M − 1SD | 0.076 | 0.083 | 0.425 | 0.751 |

| M | 0.060 | 0.064 | 0.341 | 0.593 | |

| M + 1SD | 0.045 | 0.080 | 0.188 | 0.504 |

| Regression Equation (n = 516) | Overall Fit Coefficient | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result Variables | Predictive Variables | R | R-sq | F | β | t |

| Companionship | 0.650 | 0.423 | 50.357 | |||

| Grade | 0.026 | 1.649 | ||||

| Gender | 0.054 | 1.586 | ||||

| Parent-offspring communication | 0.467 | 7.311 *** | ||||

| Safety | 0.191 | 3.026 *** | ||||

| Parent-offspring communication x sense of safety | −0.152 | −2.397 ** | ||||

| School Adaptation | 0.528 | 0.278 | 39.914 | |||

| Grade | 0.057 | 3.620 | ||||

| Gender | 0.112 | 3.253 | ||||

| Parent-offspring communication | 0.252 | 5.195 *** | ||||

| Companionship | 0.129 | 2.520 * | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Shen, B.; Deng, C.; LYu, X. The Relationship between Parent-Offspring Communication and the School Adaptation of Leftover Children in Overseas Countries: The Mediating Role of Companionship and the Moderating Role of a Sense of Safety. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070557

Zhang H, Shen B, Deng C, LYu X. The Relationship between Parent-Offspring Communication and the School Adaptation of Leftover Children in Overseas Countries: The Mediating Role of Companionship and the Moderating Role of a Sense of Safety. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(7):557. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070557

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Huilan, Bingwei Shen, Chunkao Deng, and Xiaojun LYu. 2023. "The Relationship between Parent-Offspring Communication and the School Adaptation of Leftover Children in Overseas Countries: The Mediating Role of Companionship and the Moderating Role of a Sense of Safety" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 7: 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070557

APA StyleZhang, H., Shen, B., Deng, C., & LYu, X. (2023). The Relationship between Parent-Offspring Communication and the School Adaptation of Leftover Children in Overseas Countries: The Mediating Role of Companionship and the Moderating Role of a Sense of Safety. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070557