Workaholism Scales: Some Challenges Ahead

Abstract

1. Introduction

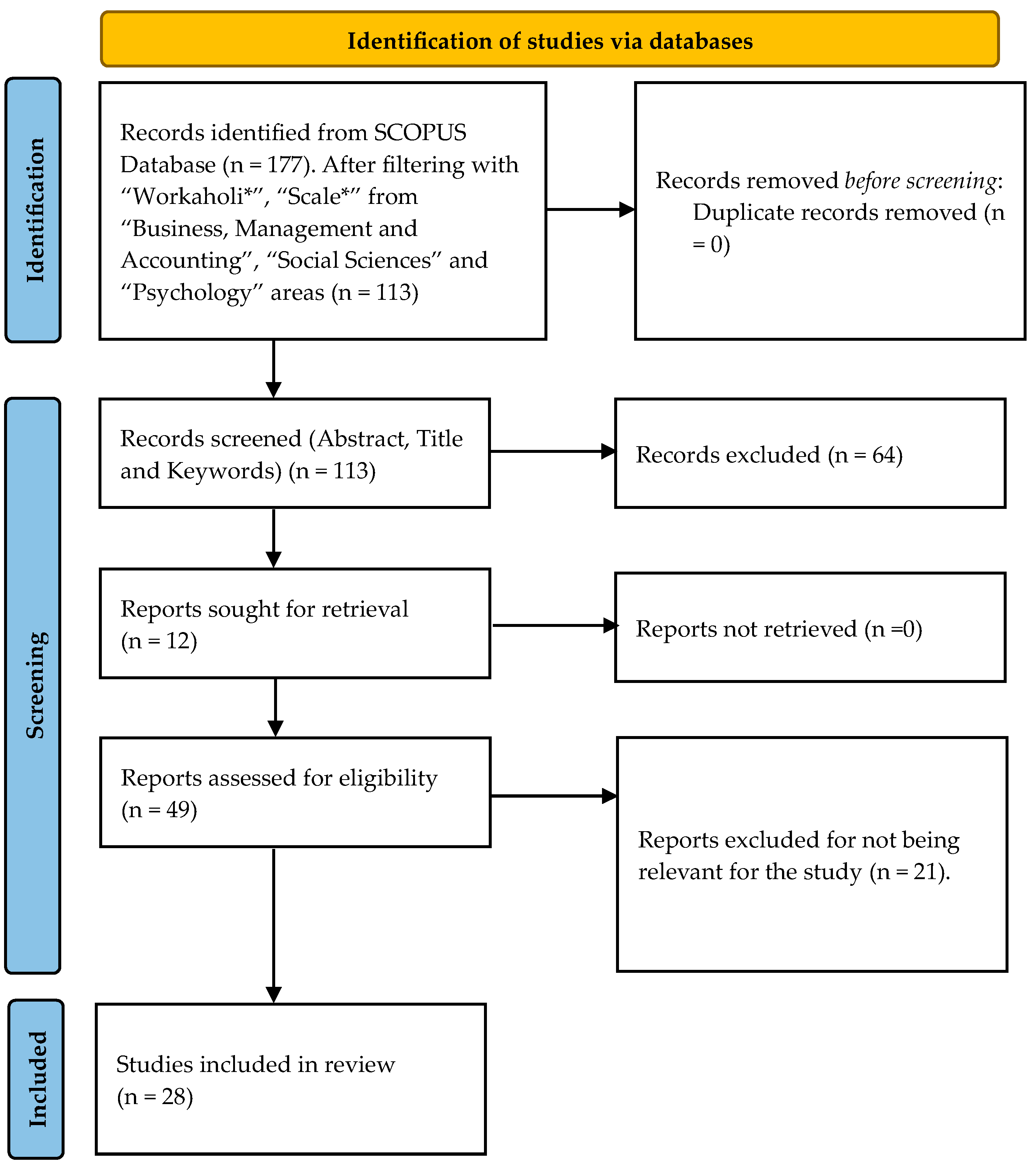

2. Methodology

- First, a review was conducted based on the research objectives.

- Secondly, manuscripts were selected based on strict criteria to guide the search in the Scopus database and to identify the scales used to measure workaholism.

- Finally, relevant information extracted from the selected articles was analyzed, and the results were discussed.

3. Results

3.1. General Characterization of the Sample

3.2. Analysis of the Main Scales

3.2.1. Work Addiction Risk Test (WART)

3.2.2. Workaholism Battery (WorkBAT)

3.2.3. Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS)

3.2.4. Bergen Work Addiction Scale (BWAS)

3.2.5. Multidimensional Workaholism Scale (MWS)

4. Discussion

- No consensus relating to the factor structure

- Its validity oscillates when used in different cultures.

- Focused on work addiction instead of workaholism, and thus only captures the negative aspects of workaholism

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oates, W. Confessions of a Workaholic: The Facts About Work Addiction; World: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, C.; Hetland, J.; Pallesen, S. Psychometric assessment of workaholism measures. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.; Griffiths, M.D.; Hetland, J.; Pallesen, J. Development of a work addiction scale. Scand. J. Psychol. 2012, 53, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador, A.; Gonçalves, A.; Martins, G.; Carvalho, L. Pathological traits and adaptability as predictors of engagement, job satisfaction, burnout and workaholism. Psicol. Teor. E Pesqui. 2022, 38, e38551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, A.; Wakabayashi, M.; Fling, S. Workaholism among employees in Japanese corporations: An examination based on the Japanese version of the Workaholism Scales. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 1996, 38, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beer, L.T.; Horn, J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Construct and criterion validity of the Dutch workaholism scale (DUWAS) within the South African financial services context. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221079879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.; Salessi, S.; Vaamonde, J.; Urteaga, F. Psychometric qualities of the Argentine version of the Dutch work addiction scale (DUWAS). Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Wijhe, C.; Peeters, M.; Taris, T. Werkverslaving, een begrip gemeten [Work addiction, a concept measured]. Gedrag En Organ. 2011, 24, 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Urbán, R.; Kun, B.; Mózes, T.; Soltész, P.; Paksi, B.; Farkas, J.; Kökönyei, G.; Orosz, G.; Maráz, A.; Felvinczi, K.; et al. A four-factor model of work addiction: The development of the work addiction risk test revised. Eur. Addict. Res. 2019, 25, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littman-Ovadia, H.; Balducci, C.; Ben-Moshe, T. Psychometric properties of the Hebrew version of the Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS-10). J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 2014, 148, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S.L.; Leiter, M.P. Key questions regarding work engagement. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, G.; Gaudiino, M. Workaholism and work engagement: How are they similar? How are they different? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkoler, O.; Rabenu, E.; Vasiliu, C.; Sharoni, G.; Tziner, A. Organizing the confusion surrounding workaholism: New structure, measure, and validation. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscalzo, Y.; Giannini, M. What type of worker are you? Work-related Inventory (WI-10): A comprehensive instrument for the measurement of workaholism. Work 2019, 62, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 15, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcerzak, A.; Nica, E.; Rogalska, E.; Poliak, M.; Klieštik, T.; Sabie, O.-M. Blockchain technology and smart contracts in decentralized governance systems. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Rasul, T. Customer engagement and social media: Revisiting the past to inform the future. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D., Bryman, A., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2009; pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Bachrach, D.; Podsakoff, N. The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.; Moreira, A. Workplace innovation: A search for its determinants through a systematic literature review. Bus. Theory Pract. 2022, 23, 502–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivares, J.A.; Avella, L.; Sarache, W. Trends and challenges in operations strategy research: Findings from a systematic literature review. Cuad. Gest. 2022, 22, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, J.; Schotten, M.; Plume, A.; Cote, G.; Karimi, R. Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2019, 1, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Singh, P.; Karmakar, M.; Leta, J.; Mayr, P. The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and dimensions: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5113–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, I.; Anderson, J.; Munim, Z.; Ho, A. A review of the internationalization of Chinese enterprises. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 573–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.T.; Robbins, A.S. Workaholism: Definition, measurement, and preliminary results. J. Personal. Assess. 1992, 58, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Shimazu, A.; Taris, T. Being driven to work excessively hard. The evaluation of a two-factor measure of workaholism in The Netherlands and Japan. Cross-Cult. Res. 2009, 43, 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Verhoeven, L.C. Workaholism in the Netherlands: Measurement and implications for job strain and work-nonwork conflict. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 54, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, L.H.W.; Brady, E.C.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Marsh, N.V. A multifaceted validation study of Spence and Robbins’ (1992) Workaholism Battery. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2002, 75, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Líbano, M.; Llorens, S.; Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W. Validación de una escala breve de adicción al trabajo. Psicothema 2010, 22, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Mudrack, P.E.; Naughton, T.J. The assessment of workaholism as behavioral tendencies: Scale development and preliminary empirical testing. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2001, 8, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Smith, R.W.; Haynes, N.J. The Multidimensional Workaholism Scale: Linking the conceptualization and measurement of workaholism. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1281–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Avanzi, L.; Consiglio, C.; Fraccaroli, F.; Schaufeli, W. A cross-national study on the psychometric quality of the Italian version of the Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2017, 33, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Hu, C.; Wu, T.C. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the workaholism battery. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 2010, 144, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, A.; Kravina, L.; Girardi, D.; Corso, L.D.; di Sipio, A.; de Carlo, N.A. The convergence between self and observer ratings of workaholism: A comparison between couples. TPM-Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 19, 311–324. [Google Scholar]

- Nonnis, M.; Cuccu, S.; Cortese, C.; Massidda, D. The Italian version of the Dutch Workaholism Scale (DUWAS): A study on a group of nurses. BPA Appl. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 65, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Boada-Grau, J.; Prizmic-Kuzmica, A.J.; Serrano-Fernández, M.J.; Vigil-Colet, A. Estructura factorial, fiabilidad y validez de la escala de adicción al trabajo (WorkBAT): Versión Española. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T.; Caesens, G.; Sandrin, É.; Gillet, N. Workaholism and work engagement: An examination of their psychometric multidimensionality and relations with employees’ functioning. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 5240–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, I.; Kamal, A.; Masood, S. Translation and validation of Dutch workaholism scale. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2016, 31, 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, J. A confirmatory factor analysis of Dutch work addiction scale (DUWAS). Glob. Bus. Rev. 2013, 14, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, A.C.S.; de Freitas, C.P.P.; Cyrre, A.; Hutz, C.S.; Schaufeli, W.B. Validity evidence of the Dutch work addiction scale-Brazilian version. Aval. Psicol. 2020, 17, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Li, C. Validation of the Chinese version of the multidimensional workaholism scale. J. Career Assess. 2021, 29, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Choi, J.; Park, Y.; Sohn, Y.W. The multidimensional workaholism scale in a Korean population: A cross-cultural validation study. J. Career Assess. 2022, 30, 258–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Kovalchuk, L.; Ghislieri, C.; Spagnoli, P. Work addiction among employees and self-employed workers: An investigation based on the Italian version of the Bergen Work Addiction Scale. Eur. J. Psychol. 2022, 18, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, B.E. Workaholism: Hidden Legacies of Adult Children; Health Communications: Deerfield Beach, FL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, B.E.; Post, P. Validity of the work addiction risk test. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1994, 78, 337–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flowers, C.P.; Robinson, B. A structural and discriminant analysis of the work addiction risk test. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2002, 62, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Bakker, A.B. It takes two to tango: Workaholism is working excessively and working compulsively. In The Long Workhours Culture: Causes, Consequences and Choices; Burke, R.J., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravina, L.; Falco, A.; Girardi, D.; De Carlo, N.A. Workaholism among management and workers in an Italian cooperative enterprise. TP-Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 17, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Sorensen, K.L.; Feldman, D.C. Dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of workaholism: A conceptual integration and extension. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Journal | Number of Articles | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied | 2 | 7% |

| Journal of Career Assessment | 2 | 7% |

| Current Psychology | 2 | 7% |

| Others | 22 | 79% |

| Year of Publication | Number of Articles | Percentage of Total Articles | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020–2023 | 9 | 32.14% | 32.14% |

| 2016–2019 | 4 | 14.28% | 46.43% |

| 2012–2015 | 7 | 25.00% | 71.43% |

| 2009–2011 | 3 | 10.71% | 82.14% |

| 1992–2005 | 5 | 17.85% | 100.00% |

| Author | Source Title | Quartile | TGC | TLC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spence and Robbins [25] | Journal of Personality Assessment | Q1 | 593 | 12 |

| Schaufeli, Shimazu et al. [26] | Cross-Cultural Research | Q1 | 310 | 8 |

| Taris et al. [27] | Applied Psychology | Q1 | 200 | 6 |

| Andreassen, Griffiths et al. [3] | Scandinavian Journal of Psychology | Q1 | 198 | 3 |

| McMillan et al. [28] | Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology | Q1 | 141 | 6 |

| Kanai et al. [5] | Japanese Psychological Research | Q2 | 121 | 6 |

| Del Libano et al. [29] | Psicothema | Q1 | 84 | 6 |

| Mudrack and Naughton [30] | International Journal of Stress Management | Q1 | 65 | 1 |

| Andreassen, Hetland et al. [2] | Journal of Managerial Psychology | Q1 | 60 | 4 |

| Clark et al. [31] | Journal of Applied Psychology | Q1 | 48 | 1 |

| Balducci et al. [32] | European Journal of Psychological Assessment | Q2 | 40 | 3 |

| Huang et al. [33] | Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied | Q1 | 26 | 2 |

| Littman-Ovadia et al. [10] | Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied | Q1 | 26 | 3 |

| Falco et al. [34] | TPM—Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology | Q2 | 21 | 0 |

| Nonnis et al. [35] | BPA Applied Psychology Bulletin | Q4 | 15 | 0 |

| Schaufeli, Wijhe et al. [8] | Gedrag en Organisatie | Q4 | 15 | 0 |

| Boada-Grau et al. [36] | Anales de Psicologia | Q2 | 11 | 0 |

| Urbán et al. [9] | European Addiction Research | Q1 | 11 | 0 |

| Huyghebaert-Zouaghi et al. [37] | Current Psychology | Q2 | 8 | 0 |

| Mir et al. [38] | Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research | Q4 | 7 | 0 |

| Sharma and Sharma et al. [39] | Global Business Review | Q2 | 6 | 0 |

| Vazquez et al. [40] | Avaliacao Psicologica | Q4 | 6 | 0 |

| Xu and Li [41] | Journal of Career Assessment | Q1 | 5 | 1 |

| Kim et al. [42] | Journal of Career Assessment | Q1 | 2 | 0 |

| de Beer et al. [6] | SAGE Open | Q2 | 1 | 0 |

| Molino et al. [43] | Europe’s Journal of Psychology | Q2 | 1 | 0 |

| Omar et al. [7] | Current Psychology | Q2 | 1 | 0 |

| Salvador et al. [4] | Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa | Q4 | 1 | 0 |

| Article | DUWAS | WorkBAT | WART | BWAS | MWS | Comparison between Scales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andreassen, Griffiths et al. [3] | X | X | X | |||

| Andreassen, Hetland et al. [2] | X | X | ||||

| Balducci et al. [32] | X | |||||

| Boada-Grau et al. [36] | X | |||||

| Clark et al. [31] | X | |||||

| de Beer et al. [6] | X | |||||

| del Líbano et al. [29] | X | |||||

| Falco et al. [34] | X | |||||

| Huang et al. [33] | X | X | ||||

| Huyghebaert-Zouaghi et al. [37] | X | |||||

| Kanai et al. [5] | X | |||||

| Kim et al. [42] | X | X | X | |||

| Littman-Ovadia et al. [10] | X | |||||

| McMillan et al. [28] | X | |||||

| Mir et al. [38] | X | |||||

| Molino et al. [43] | X | X | ||||

| Mudrack and Naughton [30] | X | |||||

| Nonnis et al. [35] | X | |||||

| Omar et al. [7] | X | X | ||||

| Salvador et al. [4] | X | |||||

| Schaufeli, Shimazu et al. [26] | X | |||||

| Schaufeli, Wijhe et al. [8] | X | |||||

| Sharma and Sharma [39] | X | X | ||||

| Spence and Robbins [25] | X | |||||

| Taris et al. [27] | X | X | ||||

| Urbán et al. [9] | X | X | X | X | ||

| Vazquez et al. [40] | X | |||||

| Xu and Li [41] | X |

| Authors | Country | Year | Name of Scale | Number of Factors | Title of Factors | Number of Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson [44] | USA | 1989 | Work Addiction Risk Test (WART) | 5 | 1. Overdoing 2. Self-Worth 3. Control-Perfectionism 4. Intimacy 5. Future Reference/Mental Preoccupation | 25 |

| Spence and Robbins [25] | USA | 1992 | Workaholism Battery (WorkBAT) | 3 | 1. Work Involvement (WI) 2. Driveness (D) 3. Work Enjoyment (E) | 25 |

| Schaufeli, Taris et al. [47]; Schaufeli, Shimazu, et al. [26] | Netherlands | 2009 | Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS) | 2 | 1. Working Excessively (WE) 2. Working Compulsively (WC) | 17 |

| Andreassen, Griffiths et al. [3] | Norway | 2012 | Bergen Work Addiction Scale (BWAS) | 1 | 1. Workaholism | 7 |

| Clark, Smith, and Haynes [25] | USA | 2020 | Multidimensional Workaholism Scale (MWS) | 4 | 1. Motivational Dimension 2. Cognitive Dimension 3. Emotional Dimension 4. Behavioral Dimension | 16 |

| Scale | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Work Addiction Risk Test (WART) |

|

|

| Workaholism Battery (WorkBAT) |

|

|

| Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS) |

|

|

| Bergen Work Addiction Scale (BWAS) |

|

|

| Multidimensional Workaholism Scale (MWS) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonçalves, L.; Meneses, J.; Sil, S.; Silva, T.; Moreira, A.C. Workaholism Scales: Some Challenges Ahead. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070529

Gonçalves L, Meneses J, Sil S, Silva T, Moreira AC. Workaholism Scales: Some Challenges Ahead. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(7):529. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070529

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonçalves, Leandro, Jéssica Meneses, Simão Sil, Tatiana Silva, and António C. Moreira. 2023. "Workaholism Scales: Some Challenges Ahead" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 7: 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070529

APA StyleGonçalves, L., Meneses, J., Sil, S., Silva, T., & Moreira, A. C. (2023). Workaholism Scales: Some Challenges Ahead. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070529