Innovations in Trauma-Informed Care: Building the Nation’s First System of Trauma-Informed Recreation Centers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Impact of Childhood Trauma

1.2. City of Cleveland and the Neighborhood Resource and Recreation Centers

1.3. Limitations of Current Trauma-Informed Models and Approaches for Recreation Centers

1.4. Building the Nation’s First System of Trauma-Informed Recreation Centers

2. Phase 1: Establishing a Trauma-Informed Foundation

2.1. Recreation Centers to Neighborhood Resource and Recreation Centers

- Youth and adult education, ranging from K-12 enrichment programs to post-education skills training.

- Job and career readiness, including career planning, job training, and job-placement services for adults.

- Health and wellness education, raising awareness of both physical and emotional issues, to aid people of all ages.

- Youth leadership and development, including use of mentors who grew up in situations similar to what youth face today and can serve as role models.

- Arts programming, both for performing and visual arts.

- Sports and recreation, including both traditional recreation sports and nontraditional ones such as fencing and rowing.

2.2. Training All Recreation Center Staff

2.3. Hiring Trained Social Workers and Counselors

2.4. Phase 1 Lessons Learned

- Adequate time for strategic planning between legislation passing and program starting should be built into the first year of the program. Strategic planning should at minimum include a 5-year plan with mapped-out goals for each year of the programs.

- Measuring organizational readiness for change and providing support in this area is recommended.

- Rather than training all recreation staff at the same time, training should be conducted in stages starting with city leadership, followed by Center Managers, and then the remaining recreation staff.

- Tools, resources, and strategies should be available to staff early on to address secondary trauma experienced by staff, particularly for recreation systems located within cities with high levels of violence and crime.

- The city should adopt a trauma-informed city-level ordinance so that all departments and divisions have a shared understanding and language around trauma.

3. Phase 2: Organizational Change

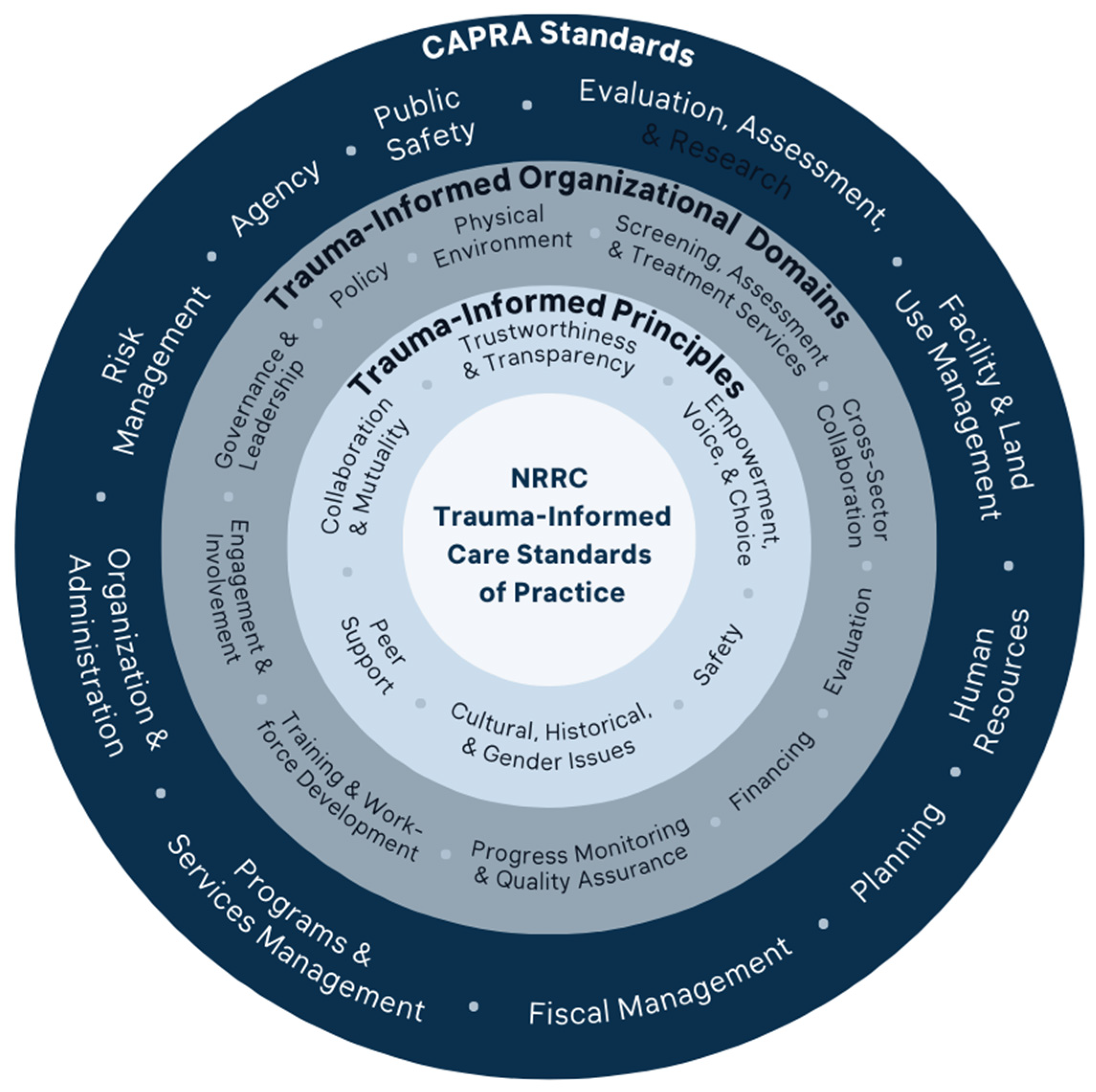

3.1. Development of the NRRC Trauma-Informed Standards

3.1.1. Benchmarking

3.1.2. Manager and Staff Feedback

3.1.3. Patron Feedback

3.1.4. Leadership Team Feedback

3.2. Development of TI-NRRC Progress Tool

3.2.1. Development of Measurable Indicators

3.2.2. Managers and Leadership Feedback

3.2.3. Pilot and Baseline Data

3.2.4. Progress Tool Report and Improvement Plan

3.3. Development of Leadership Competencies

3.3.1. Staff and Leadership Feedback

3.3.2. Infusing a Trauma-Informed Perspective

3.4. Ongoing Training for NRRC Social Workers and Counselors

3.5. Lessons Learned

4. Phase 3: The Future

4.1. All Staff Professional Development Series on Trauma-Informed Care

4.2. Expand Trauma-Informed Care Efforts to Involve Youth and Adult Community Members

4.3. Ongoing TI-NRRC Progress Tool Implementation and Improvement Plan

4.4. Trauma-Informed Policy Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jackson, M.F.; Zone, K. Toxic Stress and Trauma Management Training for Division of Recreation Staff; The City Record: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.clevelandcitycouncil.org/pdf/web/viewer.html?file=/sites/default/files/2021-11/City-Record-May-23-2018.pdf#search=toxic%20stress (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. 2014. Available online: https://calio.dspacedirect.org/handle/11212/1971 (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Bremner, J.D.; Walker, J.D.; Whitfield, C.H.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjet, C.; Bromet, E.; Karam, E.G.; Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Ruscio, A.M.; Shahly, V.; Stein, D.J.; Petukhova, M.; Hill, E.; et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giano, Z.; Wheeler, D.L.; Hubach, R.D. The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the U.S. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, A.; Turner, H.; Hamby, S. Improving the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study Scale. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire-Jack, K.; Lanier, P.; Lombardi, B. Investigating racial differences in clusters of adverse childhood experiences. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanier, P.; Maguire-Jack, K.; Lombardi, B.; Frey, J.; Rose, R.A. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Child Health Outcomes: Comparing Cumulative Risk and Latent Class Approaches. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, R.; Cronholm, P.F.; Fein, J.A.; Forke, C.M.; Davis, M.B.; Harkins-Schwarz, M.; Pachter, L.M.; Bair-Merritt, M.H. Household and community-level Adverse Childhood Experiences and adult health outcomes in a diverse urban population. Child Abuse Negl. 2016, 52, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teicher, M.H.; Samson, J.A. Annual Research Review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.; Pence, D.M.; Conradi, L. Trauma-Informed Care. In Encyclopedia of Social Work; Oxford Research Encyclopedias: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau. Quick Facts Cleveland, Ohio; US Census Bureau: Suitland, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/clevelandcityohio (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Cuyahoga County Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services (ADAMHS) Board. 2020–2021 Community Plan; Cuyahoga County Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services (ADAMHS) Board: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.adamhscc.org/resources/other-resources (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Center for Health Affairs Cuyahoga Health Improvement Partnership. Cuyahoga County Community Health Assessment Data; Center for Health Affairs Cuyahoga Health Improvement Partnership: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2019; Available online: https://hipcuyahoga.org/2019cha/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030: Social Determinants of Health; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- National Recreation and Park Association. Recreation Centers Play an Important Role in Communities. 2017. Available online: https://www.nrpa.org/publications-research/park-pulse/park-pulse-survey-recreation-centers-role-in-communities/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Damian, A.J.; Gallo, J.; Leaf, P.; Mendelson, T. Organizational and provider level factors in implementation of trauma-informed care after a city-wide training: An explanatory mixed methods assessment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, S.L. Creating Sanctuary: Toward the Evolution of Sane Societies, Revised Edition; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, S.L.; Farragher, B. Restoring Sanctuary: A New Operating System for Trauma-Informed Systems of Care; OUP USA: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.; Fallot, R.D. Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, A. Models for Developing Trauma-Informed Behavioral Health Systems and Trauma-Specific Services. 2008. Available online: https://www.theannainstitute.org/MDT.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Matlin, S.L.; Champine, R.B.; Strambler, M.J.; O'Brien, C.; Hoffman, E.; Whitson, M.; Kolka, L.; Tebes, J.K. A Community’s Response to Adverse Childhood Experiences: Building a Resilient, Trauma-Informed Community. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 64, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Creating, Supporting, and Sustaining Trauma-Informed Schools: A System Framework. 2017. Available online: https://www.nctsn.org/resources/creating-supporting-and-sustaining-trauma-informed-schools-system-framework (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Herrenkohl, T.; Miller, A.; Eisman, A.; Davis, E.; Price, D.; Robinson, Y.; Sherman, B.A. Trauma Informed Programs and Practices for Schools (TIPPS) [Program Guide]. 2021. Available online: https://tipps.ssw.umich.edu/tools/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Black, P.; Henderson-Smith, L.; Flinspach, S. Trauma-Informed, Resilience-Oriented Schools Toolkit. 2021. Available online: https://www.nc2s.org/resource/trauma-informed-resilience-oriented-schools-toolkit/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Santoro, M. Naturally Trauma-Informed: A Mixed Methods Case Study of Trauma-Informed Care Training for Frontline Parks and Recreation Staff Working in Urban After-School Programs—ProQuest. 2021. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/8a951b8a87b0b08d33c47895110ee5c2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Purtle, J. Systematic Review of Evaluations of Trauma-Informed Organizational Interventions That Include Staff Trainings. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 21, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaradeh, K.; Sergi, F.; Kivlahan, C.; Nava Gonzales, C.; Cury, M.; DeFries, T. Implementing a Trauma-Informed Approach at a Student-Run Clinic for Individuals Seeking Asylum. Acad. Med. 2023, 98, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, S.; Thomas, B. Organizational Change Explained: Case Studies on Transformational Change in Organizations; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, C.; Goodman, L. A Guide for Using the Trauma Informed Practices (TIP) Scales. 2015. Available online: dvevidenceproject.org/evaluation-tools (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Trauma Informed Oregon. Standards of Practice for Trauma Informed Care. 2015. Available online: http://traumainformedoregon.org/standards-practice-trauma-informed-care/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Evans, K.E.; Bender, A.E.; Rolock, N.; Hambrick, E.P.; Bai, R.; White, K.; Diamant-Wilson, R.; Bailey, K.A. Exploring Adherence to Client Treatment Recommendations in the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2023, 10497315231160588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, L.J.; Esaki, N.; Smith, C.A. Importance of Leadership and Employee Engagement in Trauma-Informed Organizational Change at a Girls’ Juvenile Justice Facility. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2017, 41, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J.; Harvey, S.; Esaki, N. Transformational leadership and organizational change: How do leaders approach trauma-informed organizational change… twice? Fam. Soc. 2015, 96, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.D.; Hambrick, E.P. The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. Reclaiming Child Youth 2008, 17, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Goessling, K.P. Youth participatory action research, trauma, and the arts: Designing youthspaces for equity and healing. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2020, 33, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, T.; Kenemore, T.; Mann, K.; Edwards, M.; List, C.; Martinson, K.J. The Truth N’ Trauma Project: Addressing Community Violence Through a Youth-Led, Trauma-Informed and Restorative Framework. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2015, 32, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoko, N.; Dwarakanath, N.; Macak, J.; Miller, E. 189. Youth Leadership in Action (YLIA): A Youth-Led Initiative to Improve Trauma-Sensitive School Climate. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holmes, M.R.; King, J.A.; Miller, E.K.; King-White, D.L.; Korsch-Williams, A.E.; Johnson, E.M.; Oliver, T.S.; Conard, I.T. Innovations in Trauma-Informed Care: Building the Nation’s First System of Trauma-Informed Recreation Centers. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050394

Holmes MR, King JA, Miller EK, King-White DL, Korsch-Williams AE, Johnson EM, Oliver TS, Conard IT. Innovations in Trauma-Informed Care: Building the Nation’s First System of Trauma-Informed Recreation Centers. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(5):394. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050394

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolmes, Megan R., Jennifer A. King, Emily K. Miller, Dakota L. King-White, Amy E. Korsch-Williams, Erica M. Johnson, Tomeika S. Oliver, and Ivan T. Conard. 2023. "Innovations in Trauma-Informed Care: Building the Nation’s First System of Trauma-Informed Recreation Centers" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 5: 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050394

APA StyleHolmes, M. R., King, J. A., Miller, E. K., King-White, D. L., Korsch-Williams, A. E., Johnson, E. M., Oliver, T. S., & Conard, I. T. (2023). Innovations in Trauma-Informed Care: Building the Nation’s First System of Trauma-Informed Recreation Centers. Behavioral Sciences, 13(5), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050394