Career Calling, Courage, Flourishing and Satisfaction with Life in Italian University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure of Data Collection

2.2. Measures

- Flourishing

- Life satisfaction

- Courage

- Career calling

2.3. Data Analysis

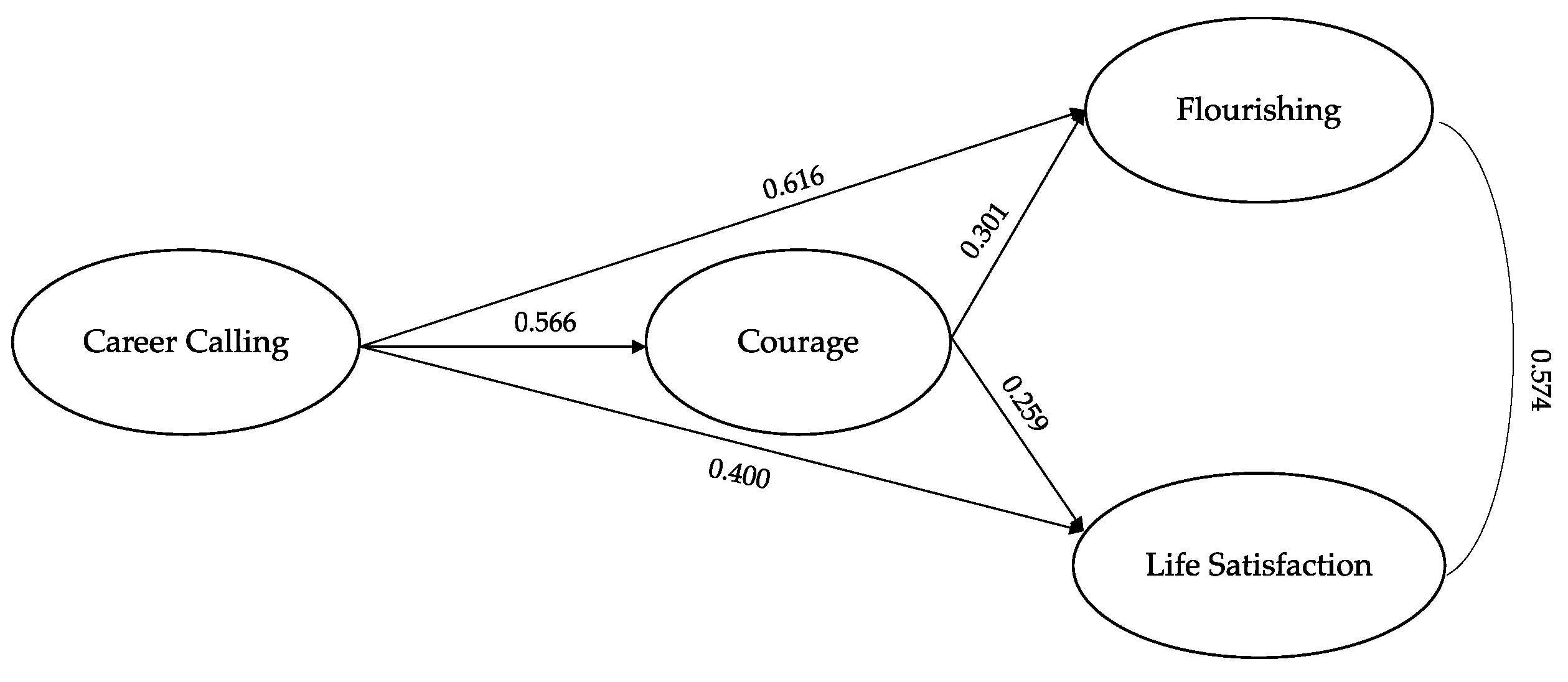

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fusco, L.; Parola, A.; Sica, L.S. Life design for youth as a creativity-based intervention for transforming a challenging World. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 662072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginevra, M.C.; Santilli, S.; Camussi, E.; Magnano, P.; Capozza, D.; Nota, L. The Italian adaptation of courage measure. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2020, 20, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Sedlacek, W.E. The salience of a career calling among college students: Exploring group differences and links to religiousness, life meaning, and life satisfaction. Career Dev. Q. 2010, 59, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Allan, B.A.; Dik, B.J. The presence of a calling and academic satisfaction: Examining potential mediators. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity and the life cycle: Selected papers. Psychol. Issues 1959, 1, 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Porfeli, E.J. Career exploration. In Career Counseling; Leong, F.T.L., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 3, pp. 1474–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M. Identity in vocational development. J. Vocat. Behav. 1985, 27, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L.; Nota, L.; Rossier, J.; Dauwalder, J.P.; Duarte, M.E.; Guichard, J.; Soresi, S.; Van Esbroeck, R.; Van Vianen, A.E. Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 75, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. Career construction theory and practice. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 2nd ed.; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Nota, L.; Rossier, J. Handbook of Life Design: From Practice to Theory and from Theory to Practice; Hogrefe: Firenze, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Santisi, G.; Magnano, P.; Platania, S.; Ramaci, T. Psychological resources, satisfaction, and career identity in the work transition: An outlook on Sicilian college students. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2018, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A. The role of chance events in the school-to-work transition: The influence of demographic, personality and career development variables. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Dik, B.J.; Douglass, R.P.; England, J.W.; Velez, B.L. Work as a calling: A theoretical model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 65, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dik, B.J.; Wei, J.; Zhang, J. Work as a calling in China: A qualitative study of Chinese college students. J. Career Assess. 2015, 23, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Herrmann, A. Calling and career preparation: Investigating developmental patterns and temporal precedence. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. A longer road to adulthood; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J.; Žukauskienė, R.; Sugimura, K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, C.M.; Arnett, J.; Palmer, C.G.; Nelson, L.J. Established adulthood: A new conception of ages 30 to 45. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrow, S.R.; Tosti-Kharas, J. Calling: The development of a scale measure. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 1001–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.T.; Chandler, D.E. Psychological success: When the career is a calling. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.; Griffin, M.A.; Parker, S.K. Future work selves: How salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Calling and vocation at work: Definitions and prospects for research and practice. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 37, 424–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, I.; Dik, B.J.; Banning, J.H. College students’ perceptions of calling in work and life: A qualitative analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Pickering, N.K.; Shin, J.Y.; Dik, B.J. Calling in work: Secular or sacred? J. Career Assess. 2010, 18, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Bott, E.M.; Allan, B.A.; Torrey, C.L.; Dik, B.J. Perceiving a calling, living a calling, and job satisfaction: Testing a moderated, multiple mediator model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 59, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.; Park, N.; Hall, N.; Seligman, M.E. Zest and work. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2009, 30, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Dik, B.J. Research on calling: What have we learned and where are we going? J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well–Being; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zyl, L.E.; Stander, M.W. Flourishing interventions: A practical guide to student development. In Psycho-Social Career Meta-Capacities: Dynamics of Contemporary Career Development; Coetzee, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, S. The interplay of courage and reason in moral action. Hist. Hum. Sci. 2011, 24, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, D. Philosophical roots of the concept of courage. In The Psychology of Courage: Modern Research on an Ancient Virtue; Pury, C.L.S., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, S.J.; Rasmussen, H.N.; Skorupski, W.P.; Koetting, K.; Petersen, S.E.; Yang, Y. Folk conceptualizations of courage. In The Psychology of Courage: Modern Research on an Ancient Virtue; Pury, C.L.S., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rate, C.R. Defining the features of courage: A search for meaning. In The Psych-Ology of Courage: Modern Research on an Ancient Virtue; Pury, C.L.S., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, C. The psychology of courage: Modern research on an ancient virtue. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2011, 45, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, K.; Morse, J.; Mitcham, C. Ethical sensitivity in professional practice: Concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaSala, C.; Bjarnason, D. Creating workplace environments that support moral courage. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2010, 15, 1F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, I.B.; Barbosa da Silva, A.; Berg, A.; Severinsson, E. Courage and nursing practice: A theoretical analysis. Nurs. Ethics 2010, 17, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, P.J.; Weiss, B.J. The role of courage on behavioral approach in a fear-eliciting situation: A proof-of-concept pilot study. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rate, C.R.; Clarke, J.A.; Lindsay, D.R.; Sternberg, R.J. Implicit theories of courage. J. Posit. Psychol. 2007, 2, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, C.R. Hardiness and the concept of courage. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2004, 56, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U. Emancipatory catastrophism: What does it mean to climate change and risk society? Curr. Sociol. 2015, 63, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, C. Humanistic Cognitive Behavioral Theory, a value-added approach to teaching theories of personality. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnano, P.; Lodi, E.; Zammitti, A.; Patrizi, P. Courage, career adaptability, and readiness as resources to improve well-being during the University-to-Work Transition in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockorny, K.M. Psychological Capital, Courage, and Entrepreneurial Success. Ph.D. Thesis, Bellevue University, Bellevue, NE, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gustems, J.; Calderon, C. Character strengths and psychological wellbeing among students of teacher education. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 3, 265–286. [Google Scholar]

- Toner, E.; Haslam, N.; Robinson, J.; Williams, P. Character strengths and wellbeing in adolescence: Structure and correlates of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Children. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnano, P.; Santisi, G.; Zammitti, A.; Zarbo, R.; Di Nuovo, S. Self-perceived employability and meaningful work: The mediating role of courage on quality of life. Sustainability 2019, 11, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, M.C.; Magnano, P.; Lodi, E.; Annovazzi, C.; Camussi, E.; Patrizi, P.; Nota, L. The role of career adaptability and courage on life satisfaction in adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2018, 62, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. Flourishing Scale: Primo contributo alla validazione della versione italiana. Counseling 2016, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A.; Gori, A. Measuring adolescent life satisfaction: Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale in a sample of Italian adolescents and young adults. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2016, 34, 501–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianello, M.; Dalla Rosa, A.; Anselmi, P.; Galliani, E.M. Validity and measurement invariance of the Unified Multidimensional Calling Scale (UMCS): A three-wave survey study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, T.D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K.F. To Parcel or not to Parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multi-Discip. J. 2002, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Rhemtulla, M.; Gibson, K.; Schoemann, A.M. Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol. Methods 2013, 18, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyle, R.H. Handbook of Strucural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A.A.; Panzeri, A.; Taccini, F.; Parola, A.; Mannarini, S. The Rising of the Shield Hero. Development of the Post-Traumatic Symptom Questionnaire (PTSQ) and Assessment of the Protective Effect of Self-Esteem from Trauma-Related Anxiety and Depression. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2022, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoffcriteria for t indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammitti, A. Career planning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Training for strengthening courage and career adaptability and lowering fear levels of COVID-19. Psychol. Hub 2021, 38, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Argyropoulou, K.; Kaliris, A.; Charokopaki, A.; Katsioula, P. Coping with career indecision: The role of courage and future orientation in secondary education students from Greek provincial cities. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2021, 21, 671–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, A.; Marcionetti, J. Positive Resources for Flourishing: The Effect of Courage, Self-Esteem, and Career Adaptability in Adolescence. Societies 2022, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, L. Career choices and development: Post-secondary education career transitions in Italy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Naples Federico II, Napoli, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, S.F. Courage and caring: Step up to your next level of nursing excellence. Patient Care Manag. 2003, 19, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J.M.; Grant, A.M.; Johnson, V. When callings are calling: Crafting work and leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 973994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmaier, T.; Abele, A.E. The multidimensionality of calling: Conceptualization, measurement and a bicultural perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 81, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FS | 5.82 | 0.89 | - | |||||||||

| 2 | LS | 4.96 | 1.32 | 0.688 | - | ||||||||

| 3 | CS | 5.56 | 0,96 | 0.543 | 0.420 | - | |||||||

| 4 | CALL_PASS | 5.63 | 1.17 | 0.674 | 0.555 | 0.342 | - | ||||||

| 5 | CALL_SAC | 5.57 | 1.26 | 0.615 | 0.500 | 0.440 | 0.786 | - | |||||

| 6 | CALL_TrS | 4.95 | 1.68 | 0.506 | 0.396 | 0.352 | 0.557 | 0.531 | - | ||||

| 7 | CALL_PRO | 5.83 | 1.13 | 0.532 | 0.347 | 0.322 | 0.492 | 0.497 | 0.584 | - | |||

| 8 | CALL_PER | 4.87 | 1.46 | 0.458 | 0.318 | 0.307 | 0.581 | 0.584 | 0.479 | 0.513 | - | ||

| 9 | CALL_PUR | 5.67 | 1.13 | 0.444 | 0.216 | 0.377 | 0.499 | 0.556 | 0.349 | 0.458 | 0.573 | - | |

| 10 | CALL_IDE | 5.67 | 1.12 | 0.597 | 0.349 | 0.464 | 0.587 | 0.595 | 0.554 | 0.518 | 0.615 | 0.709 | - |

| 11 | CALLING | 5.46 | 1.01 | 0.691 | 0.489 | 0.470 | 0.815 | 0.823 | 0.766 | 0.735 | 0.797 | 0.734 | 0.822 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parola, A.; Zammitti, A.; Marcionetti, J. Career Calling, Courage, Flourishing and Satisfaction with Life in Italian University Students. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040345

Parola A, Zammitti A, Marcionetti J. Career Calling, Courage, Flourishing and Satisfaction with Life in Italian University Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(4):345. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040345

Chicago/Turabian StyleParola, Anna, Andrea Zammitti, and Jenny Marcionetti. 2023. "Career Calling, Courage, Flourishing and Satisfaction with Life in Italian University Students" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 4: 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040345

APA StyleParola, A., Zammitti, A., & Marcionetti, J. (2023). Career Calling, Courage, Flourishing and Satisfaction with Life in Italian University Students. Behavioral Sciences, 13(4), 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040345