Abstract

Depression is a common mental health issue that affects 280 million people in the world with a high mortality rate, as well as being a leading cause of disability. Psychopharmacological therapies with psychedelics, particularly those with psilocybin, are showing promising potential for the treatment of depression, among other conditions. Some of their benefits include a rapid and exponential improvement in depressive symptoms and an increased sense of well-being that can last for months after the treatment, as well as a greater development of introspective capacity. The aim of this project was to provide experimental evidence about therapeutic procedures along with psilocybin for the treatment of major depressive disorder. The project highlights eight studies that examined this condition. Some of them dealt with treatment-resistant depression while others dealt with depression due to a life-threatening disease such as cancer. These publications affirm the efficiency of the psilocybin therapy for depression, with only one or two doses in conjunction with psychological support during the process.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization [1], depression is a common illness, affecting approximately 280 million people worldwide. About 700,000 people with depression die by suicide each year, making it the second leading cause of death in young people aged 15 to 29 and a leading global cause of disability. Despite the existence of effective pharmacological therapies for depression, there is limited efficacy to this form of treatment. At times, it produces adverse effects and adherence problems in patients [2]. It has been predicted that 23% of patients with major depression will remit within 13 weeks without any treatment [3]. According to a study by Kolovos et al. [4], traditional treatments for depression have a remission rate of 33%, which is only 10% higher than those who remit without treatment. It is necessary to develop and investigate innovative and efficient alternative treatments after taking into account these factors and the considerable negative impact of this condition on public health [5].

Psilocybin is a natural tryptamine compound found in certain species of mushrooms. Its structure and mechanisms of action are similar to those of serotonin. Despite being classified as a Schedule I drug in the US, it is becoming popular again for therapeutic purposes, even though it has been used for thousands of years for healing and spiritual purposes. Clinical studies with psilocybin for depression treatment, among various treatment-resistant disorders, have yielded satisfactory results, increasing the amount of evidence over time and offering a promising paradigm for psychology and psychiatry [6,7].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

In April 2022, a literature search following the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis declaration guide [8] was conducted to identify studies that evaluated psychological therapy combined with psilocybin for the treatment of depression. The search was carried out on databases such as ProQuest, PsycInfo, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Scopus, using the keywords “psilocybin” and the name of each disorder, along with their derivatives and synonyms, using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” (“psilocybin” AND depress* AND [“therapy” OR “support” OR “treatment”]). The search was limited so that the keywords appeared in the title in all the databases. In addition, a manual search was carried out based on the bibliographic references of the selected publications. Data extracted from each study included the country, objective, condition, design, participants, treatment, dose, measurement instruments, results, and conclusions.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were based on research articles that focused on psychological treatment of depression supplemented with psilocybin. Those treatments were conducted in any population, in either English or Spanish, and without a date limit, as it is considered relevant to include all scientific evidence in a timeless manner, and without restrictions on the type of clinical trial. Documents such as theses, reports, book chapters, study protocols, descriptive articles, and reviews of other articles were excluded, as well as those that did not use the substance for therapeutic purposes and those based solely on pharmacological treatment. Exclusion criteria also included those that focused exclusively on spiritual experiences without measuring psychological variables, as well as those that primarily discussed the physiological effects of psilocybin on the brain.

2.3. Search Flow

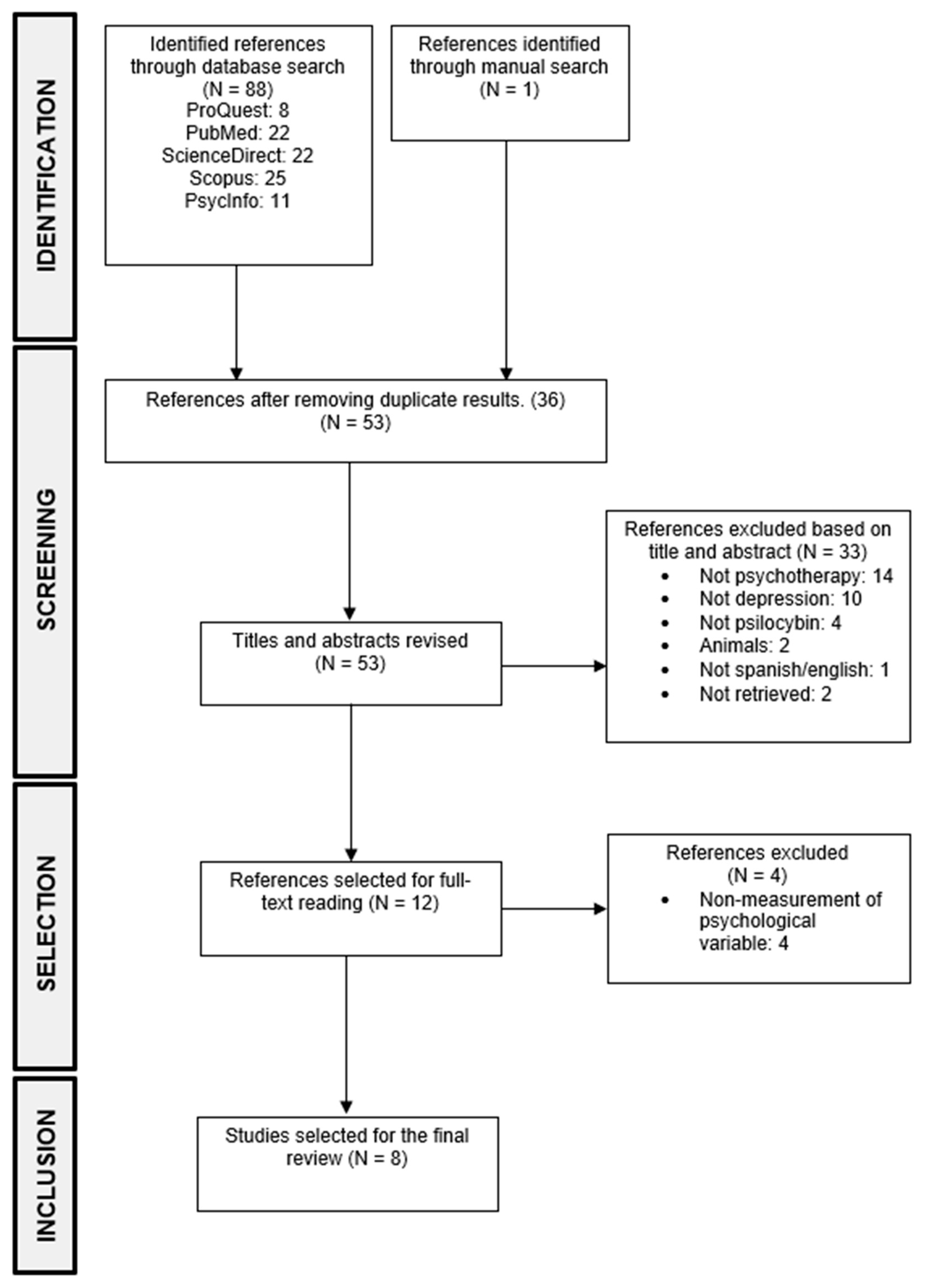

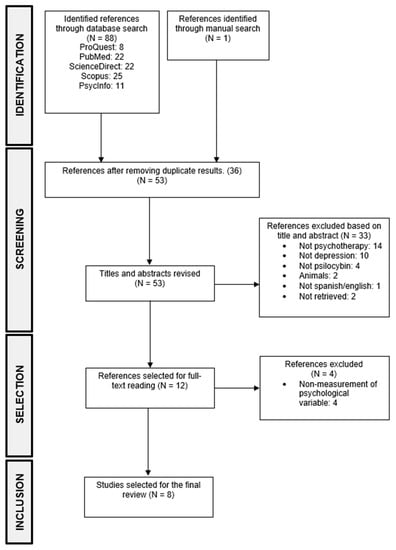

Of the 88 studies that were identified during the search, 52 were selected after eliminating duplicates. After analyzing titles and abstracts, 11 articles were chosen for full-text reading. Additionally, one study was added based on the bibliographic references of the selected articles, resulting in a total of 12 articles selected for full-text reading, as the others did not meet the inclusion criteria. Following this, a full-text reading was conducted, and four more articles were excluded as they met exclusion criteria, leaving eight articles for extracting relevant information to perform the results’ analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection.

3. Results

The most relevant data from the eight articles that met the inclusion criteria are presented below.

3.1. Objective of the Studies

All selected papers focus on psilocybin therapy to treat depressive disorder. However, certain differences should be mentioned regarding this condition, such as studies on patients who suffer from depressive symptoms due to their oncological situation [9,10] or in cases where the depressive disorder is treatment-resistant [11,12,13]. Furthermore, one of the included studies was based on the comparison of treatments between psilocybin and escitalopram [14].

3.2. Study Design

Of the eight studies analyzed, five had a randomized controlled design [2,9,10,14,15], with three of these five being double-blind [9,10,12] and two being crossover studies [9,10]. The remaining three studies were open-label trials [11,12,13].

3.3. Participants

The sample sizes ranged from 12 to 59 participants [9,14] with an age range of 39 to 56 years [9,15]. Regarding the sex of the patients, the number of males was higher than females in six out of eight studies, except for Davis et al. [2] and Gukasyan et al. [15]. The study by Carhart-Harris et al. [11] was the only one with an equal number of males and females (n = 6).

3.4. Treatment

It should be noted that certain studies share treatment due to their relationship, either by the same author [11,12,13] or to performing long-term follow-up [2,15].

The therapeutic processes carried out in these studies share several factors, beginning with preparatory sessions prior to dosing. The preparation period had a variable duration range, from just one session [11,12,13,14] to three or more sessions over several weeks [2,9,10,15]. The goal of the preparatory sessions is to discuss the participants’ history and the dosing procedure, but especially to create a therapeutic alliance. Following this procedure, two dosing sessions took place in all studies, which lasted between 6 and 8 h, in a cozy environment, in a reclined and comfortable position, with eyes closed and music therapy or with psychotherapy in the case of Ross et al. [9]. In studies with music therapy, therapists accompany patients during the process, adopting a non-directive and supportive attitude, allowing the patient to experience the inner experience uninterrupted. Generally, the doses had a one-week delay, except for the study by Giffiths et al. [10], in which they were delayed by five weeks, or Ross et al. [9], with a seven-week delay. Finally, after each dose, integration sessions were conducted, dedicated to listening to patients’ testimonies and occasionally providing some interpretation regarding the content of the experience and its potential meaning, in addition to helping process and develop a personal sense while maintaining positive aspects of it. The number of integration sessions varied between totals of two [11,12,13], four [2,15], or six [9,10].

The duration of the treatment phase varied between studies, although it was not specifically stated in some [11,12,13]; it ranged from 6 weeks [14] and 8 weeks [2,15] to several months [9].

A description of these issues is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Authors, objectives, conditions, designs, participants, and treatments of the studies.

3.5. Dosage

The range of psilocybin doses went from a moderate dose of 10 mg in the first sessions [11,12,13] to high doses of 30 mg/70 kg in the second sessions [2,15]. It is also worth noting that in double-blind studies, a small enough dose of psilocybin was used to act as a placebo, being 1 mg/70 kg [10] or 250 mg of niacin [9]. However, the most commonly used doses were 25 mg of psilocybin, in four of the eight studies [11,12,13].

3.6. Evaluation Measures

The evaluation measures used were quantitative in all studies, focusing solely on depressive symptoms. The most commonly used instruments were the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [9,10,11,12,13,15], Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS) [2,11,13,14,15], and GRID–Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (GRID-HAMD) or its variant HAM-D [10,11,13,15]. The less common instruments were the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [13], Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) [13], and Prediction of Future Life Events (POFLE, 2006) [12]. The latter consists of predicting the possibility of certain desirable and undesirable everyday situations over a period of 30 days. After that time period, patients must indicate which situations have occurred.

3.7. Synthesis of the Results

The results of all studies showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms after treatment with one or two doses of psilocybin. Symptomatic improvement was immediate in some cases, showing significant results one day [2,9] and one week after the second dose [2,11,12,13]. This improvement was long-lasting, maintaining significant reduction up to 6 [10,13], 8 [9], and 12 months [15]. Regarding the comparative treatment between psilocybin and escitalopram [14], no significant differences were found between both at the sixth week. Although secondary evaluation measures mostly favor psilocybin treatment, firm conclusions cannot be established as confidence intervals have not been adjusted in several comparisons. Nonetheless, both treatments were effective, and the study may have been underpowered to detect small differences.

On the other hand, moderate/high doses of psilocybin, compared to placebo or low doses of such a substance, showed considerably greater treatment efficiency. For example, in the study by Griffiths et al. [10], the group with a high amount of psilocybin in the first dose showed a much greater reduction in symptoms than the group with a low amount. However, when crossing the doses, the scores of the group with the low dose in the first place resembled the scores of the high-dose group. These observations were also demonstrated similarly in the study by Ross et al. [9], using niacin as a placebo instead of a low dose of psilocybin. These results demonstrate that a single moderate/high dose of psilocybin produces a significant improvement in symptoms.

In addition, all studies, except one [14], provided information regarding the magnitude of the differences, with effect sizes being large at all measurement points, favoring treatment with psilocybin. Finally, in six of the eight studies [2,9,10,11,14,15], adverse effects produced by psilocybin were mostly headaches, dizziness, nausea, and tachycardia, occurring occasionally and with moderate or mild intensity, not hindering treatment, and no cases of addiction to the substance were reported after treatment. It should also be noted that in the study by Carhart-Harris et al. [14], the adverse effects of the psilocybin and escitalopram groups were similar.

A description of these issues can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dosage, measurement instruments, results, and conclusions of the studies.

4. Discussion

The objective of this work has been to present a review of therapies that have used psilocybin to treat depressive symptoms, as well as a synthesis of the effectiveness of this treatment. Eight studies have been found that focus on this treatment, with one of them being a comparison with escitalopram.

After analyzing the studies, the importance of the therapist’s role in the course of this substance is frequently emphasized. In the first place, building a therapeutic alliance is crucial for facilitating the initial stages of this experience The therapist must forge a sense of trust and closeness with the patient, which is necessary for them to feel comfortable and safe with undergoing the unfamiliar psilocybin therapy and to be sufficiently prepared for it. Unlike many other drugs, the use of this substance requires the therapists to accompany the patients throughout the transitory effect of this substance, as it leads them to an abstract and individual realm, making it important for the therapists to provide guidance and support throughout the experience. In addition, the therapists play a crucial role in helping the patients integrate the thoughts, feelings, and emotions stimulated by the experience. It is important to note that the setting in which the therapy is carried out is also significant, as it facilitates the revelation of the patients’ inner landscape. The ideal environment is a quiet space, in a reclined position, wearing an eye mask, and engaging in music therapy.

The effectiveness of the treatments is noteworthy, leading to optimal results in a few sessions. The fact that patients showed a rapid reduction in depressive symptoms as early as one day or one week after a dose highlights the difference compared to traditional treatments with other antidepressant drugs, which generally require at least two weeks to take effect with daily administration [16], and may take 6 to 12 months to produce optimal improvement [17]. Although the study by Carhart-Harris et al. [14] did not find significant differences between both drugs, the duration of the antidepressant effect of psilocybin up to several weeks with a single dose could facilitate the progress by avoiding daily medication. This might also improve the adherence to treatment, which is poor, with only around 50% [18] of patients treated with classical antidepressants, in addition to having limited efficacy, with 30–50% of patients not responding to treatment and 10–30% completely resistant to treatment [2].

Although it was not mentioned in the review, the influence of the spiritual experience is worth noting. This factor has been evaluated in more than half of the studies presented [9,10,11,12,15] and represents an important subjective component that contributes to attitudinal and behavioral improvement. That is, the intensity and quality of the psychedelic experience can act as a predictor of the maintenance of mental health benefits in the medium and long term [19,20].

The consumption of psilocybin or any psychoactive substance can produce psychotic symptoms such as delusions, panic attacks, and depersonalization [21,22]. However, when carried out in a controlled context, adverse effects are limited (headaches, dizziness, nausea, and tachycardia), as mentioned earlier. It is important to note that these adverse effects are mild or moderate and merely transient, unlike classical antidepressants, which mainly cause dizziness, gastrointestinal problems, and sexual dysfunction, among others [23,24], more continuously since such treatment involves repeated consumption. In addition, the studies presented in this work did not report any cases of potential abuse or addiction to psilocybin, being a substance with a low addictive risk and no evidence that it causes any withdrawal symptoms [2,25].

Regarding the limitations that have been presented in the development of this work, one of them is the scarcity of articles that evaluate the effectiveness of this treatment experimentally or in comparison with other traditional drugs. Additionally, it should also be noted that there was no access to scientific articles that would have been interesting for the review. Another limitation would be that, given the limited scope of this work, it was not possible to include articles that examine the treatment of other psychological disorders. Nevertheless, a satisfactory analysis of a significant part of this field has been carried out. It should be noted that half of the studies have been carried out in the United States [2,9,10,15] and the other half in the United Kingdom [11,12,13,14], which leads to the conclusion that there is a lack of population representativeness. Two other factors to consider regarding the study sample would be the imbalance between men and women, as there has been a great disparity in the present studies, and the participants’ history of substance use, as having experience with psychedelics or other drugs could bias adaptation to the treatment.

There is a certain homogeneity among the authors in this research area, with Carhart-Harris and Griffiths being the main researchers and inspirers of most of the studies with psilocybin. The combination of this factor with limited experimental support means that the number of studies conducted on this topic is relatively small, with many of the studies using similar or related experimental conditions. It would be convenient to carry out a broader reflection on procedural differences, such as variability in doses, treatment, or a greater number of studies with a double-blind and controlled design, in order to have more experimental rigor. Regarding the study design, an important factor to consider is the influence of the type of preparation prior to the doses, as certain expectations could bias the procedure when combined with a placebo, facilitating the identification of the substance and thus hindering the double-blind design. In addition, another aspect that should be controlled in future clinical trials is the effect of expectancy masking. These elements should be taken into account and be measured routinely, as discussed in the work of Muthukumaraswamy et al. [26].

Future research in this area could explore the po31tential benefits of other types of more extensive therapeutic interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral or acceptance and commitment therapy [27]. Given that most of the studies presented in this review used music therapy in conjunction with minimal therapeutic intervention (mainly non-directive psychological support), it would be valuable to investigate the influence of different types of psychotherapy of the effectiveness on this modality. Likewise, investigating which psychotherapies would be more functional in relation to high or low doses of psilocybin would help expand its effectiveness and extension to other sociocultural and economic levels.

As mentioned earlier, the spiritual factor could be of utmost importance in terms of patients’ experience and improvement during the treatment. It would be interesting to explore this topic and have more solid references, so that it is easier for professionals to understand and guide patients during their spiritual experiences.

Other important factors to consider, apart from the focus of this review, could be the extrapolation of psilocybin therapy for the treatment of other disorders. So far, research has been found experimenting with its efficacy with anxiety, a factor that is valued in some articles presented in this review [9,10] and addictions, such as alcoholism [28,29,30] or smoking [31,32,33], as well as speculations regarding its possible effectiveness for obsessive-compulsive disorder [34] and post-traumatic stress disorder [35,36,37], among others. The inclusion of different psychotherapies evidenced for these disorders and the development of procedural guides and structures [29,38] to prepare and adapt professionals to these types of therapies could represent a revolutionary expansion of therapeutic approaches.

Finally, although there is limited evidence of the use of psilocybin in non-clinical populations, recent studies have suggested its potential benefits. For example, research has shown that microdosing in healthy individuals can have positive effects on personality traits and yield promising results. Given this, exploring the use of microdoses in this population may be a worthwhile avenue for further research [39,40,41].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, psilocybin treatment for depression represents a promising paradigm for the fields of psychology and psychiatry. The growing number of experimental studies that demonstrate the efficiency of this substance highlights its therapeutic potential and minimizes adverse effects. Therefore, even though psilocybin is still classified as a harmful substance due to its legal and cultural history it could lead to a positive revolution in this field and become a novel antidepressant intervention. By carrying out a procedurally appropriate and adaptive use, it could significantly expand the range of possible medical applications, such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, addictions, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- OMS. Depresión. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Davis, A.K.; Barrett, F.S.; May, D.G.; Cosimano, M.P.; Sepeda, N.D.; Johnson, M.W.; Finan, P.H.; Griffiths, R.R. Effects of Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy on Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteford, H.A.; Harris, M.G.; McKeon, G.; Baxter, A.; Pennell, C.; Barendregt, J.J.; Wang, J. Estimating remission from untreated major depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2012, 43, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolovos, S.; van Tulder, M.W.; Cuijpers, P.; Prigent, A.; Chevreul, K.; Riper, H.; Bosmans, J.E. The effect of treatment as usual on major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 210, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, S.B.; Pace, B.T.; Nicholas, C.R.; Raison, C.L.; Hutson, P.R. The experimental effects of psilocybin on symptoms of anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, H.; Toyang, N.; Steele, B.; Valentine, H.; Grant, J.; Ali, A.; Ngwa, W.; Gordon, L. The Therapeutic Potential of Psilocybin. Molecules 2021, 26, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, T.; Wright, K. The frontiers of new psychedelic therapies: A survey of sociological themes and issues. Sociol. Compass 2022, 16, e12959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. Declaración PRISMA: Una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Med. Clin. 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Bossis, A.; Guss, J.; Agin-Liebes, G.; Malone, T.; Cohen, B.; Mennenga, S.E.; Belser, A.; Kalliontzi, K.; Babb, J.; et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W.; Carducci, M.A.; Umbricht, A.; Richards, W.A.; Richards, B.D.; Cosimano, M.P.; Klinedinst, M.A. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Bolstridge, M.; Rucker, J.; Day, C.M.J.; Erritzoe, D.; Kaelen, M.; Bloomfield, M.; Rickard, J.A.; Forbes, B.; Feilding, A.; et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: An open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. More Realistic Forecasting of Future Life Events After Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Bolstridge, M.; Day, C.M.J.; Rucker, J.; Watts, R.; Erritzoe, D.E.; Kaelen, M.; Giribaldi, B.; Bloomfield, M.; Pilling, S.; et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: Six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.; Giribaldi, B.; Watts, R.; Baker-Jones, M.; Murphy-Beiner, A.; Murphy, R.; Martell, J.; Blemings, A.; Erritzoe, D.; Nutt, D.J. Trial of Psilocybin versus Escitalopram for Depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1402–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gukasyan, N.; Davis, A.K.; Barrett, F.S.; Cosimano, M.P.; Sepeda, N.D.; Johnson, M.W.; Griffiths, R.R. Efficacy and safety of psilocybin-assisted treatment for major depressive disorder: Prospective 12-month follow-up. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 36, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmer, C.J.; Goodwin, G.M.; Cowen, P.J. Why do antidepressants take so long to work? A cognitive neuropsychological model of antidepressant drug action. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, A.; Benmansour, S. Delayed pharmacological effects of antidepressants. Mol. Psychiatry 2002, 7, S23–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, R.; Sansone, L. Antidepressant adherence: Are Patients Taking Their Medications? Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 9, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Richards, W.A.; McCann, U.; Jesse, R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology 2006, 187, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseman, L.; Nutt, D.J.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Quality of Acute Psychedelic Experience Predicts Therapeutic Efficacy of Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 8, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassman, R.J. Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. A review of the literature. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1984, 172, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziff, S.; Stern, B.; Lewis, G.; Majeed, M.; Gorantla, V.R. Analysis of Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy in Medicine: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e21944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, A.A.; Lewis, S.; Nutt, D.; Peters, T.J.; Cowen, P.; O’Donovan, M.C.; Wiles, N.; Lewis, G. Adverse effects from antidepressant treatment: Randomised controlled trial of 601 depressed individuals. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 2921–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uher, R.; Farmer, A.; Henigsberg, N.; Rietschel, M.; Mors, O.; Maier, W.; Kozel, D.; Hauser, J.; Souery, D.; Placentino, A.; et al. Adverse reactions to antidepressants. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.W.; Griffiths, R.R.; Hendricks, P.S.; Henningfield, J.E. The abuse potential of medical psilocybin according to the 8 factors of the Controlled Substances Act. Neuropharmacology 2018, 142, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukumaraswamy, S.D.; Forsyth, A.; Lumley, T. Blinding and expectancy confounds in psychedelic randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloshower, J.; Krause, R.; Gus, J. The Yale Manual for Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy of Depression (using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a Therapeutic Frame). PsyarXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agin-Liebes, G. The Role of Self-Compassion in Psilocybin-Assisted Motivational Enhancementtherapy to Treat Alcohol Dependence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ph.D. Thesis, Palo Alto University, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschutz, M.P.; Forcehimes, A.A. Development of a Psychotherapeutic Model for Psilocybin-Assisted Treatment of Alcoholism. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2016, 57, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaden, D.B.; Berghella, A.P.; Regier, P.S.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Johnson, M.W.; Hendricks, P.S. Classic psychedelics in the treatment of substance use disorder: Potential synergies with twelve-step programs. Int. J. Drug Policy 2021, 98, 103380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Romeu, A.; Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2014, 7, 157–164. Available online: http://publicaciones.umh.es/scholarly-journals/psilocybin-occasioned-mystical-experiences/docview/1659765884/se-2?accountid=28939 (accessed on 8 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Griffiths, R.R. Potential Therapeutic Effects of Psilocybin. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Cosimano, M.P.; Griffiths, R.R. Pilot study of the 5-HT^sub 2A^R agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. J. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 28, 983. Available online: http://publicaciones.umh.es/scholarly-journals/pilot-study-5-ht-sub-2a-r-agonist-psilocybin/docview/1620421697/se-2 (accessed on 8 November 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugo-Radillo, A.; Cortes-Lopez, J.L. Long-term Amelioration of OCD Symptoms in a Patient with Chronic Consumption of Psilocybin-containing Mushrooms. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2020, 53, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krediet, E.; Bostoen, T.; Breeksema, J.; Van Schagen, A.; Passie, T.; Vermetten, E. Reviewing the Potential of Psychedelics for the Treatment of PTSD. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 23, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B. Compass Will Study Its Psilocybin Drug As PTSD Therapy In Phase 2 Trial. InsideHealthPolicy.com’s Daily Brief. Available online: http://publicaciones.umh.es/trade-journals/compass-will-study-psilocybin-drug-as-ptsd/docview/2594517792/se-2?accountid=28939 (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Henner, R.L.; Keshavan, M.S.; Hill, K.P. Review of potential psychedelic treatments for PTSD. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 439, 120302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, J. Developing Guidelines and Competencies for the Training of Psychedelic Therapists. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2017, 57, 450–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Petranker, R.; Rosenbaum, D.; Weissman, C.R.; Dinh-Williams, L.-A.; Hui, K.; Hapke, E.; Farb, N.A.S. Microdosing psychedelics: Personality, mental health, and creativity differences in microdosers. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, T.; Amada, N.; Jungaberle, H.; Schecke, H.; Klein, M. Microdosing psychedelics: Motivations, subjective effects and harm reduction. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 75, 102600. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095539591930307X (accessed on 8 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Rucker, J.J.; Marwood, L.; Ajantaival, R.-L.J.; Bird, C.; Eriksson, H.; Harrison, J.; Lennard-Jones, M.; Mistry, S.; Saldarini, F.; Stansfield, S.; et al. The effects of psilocybin on cognitive and emotional functions in healthy participants: Results from a phase 1, randomised, placebo-controlled trial involving simultaneous psilocybin administration and preparation. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 36, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).