Relationship between Grateful Disposition and Subjective Happiness of Korean Young Adults: Focused on Double Mediating Effect of Social Support and Positive Interpretation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

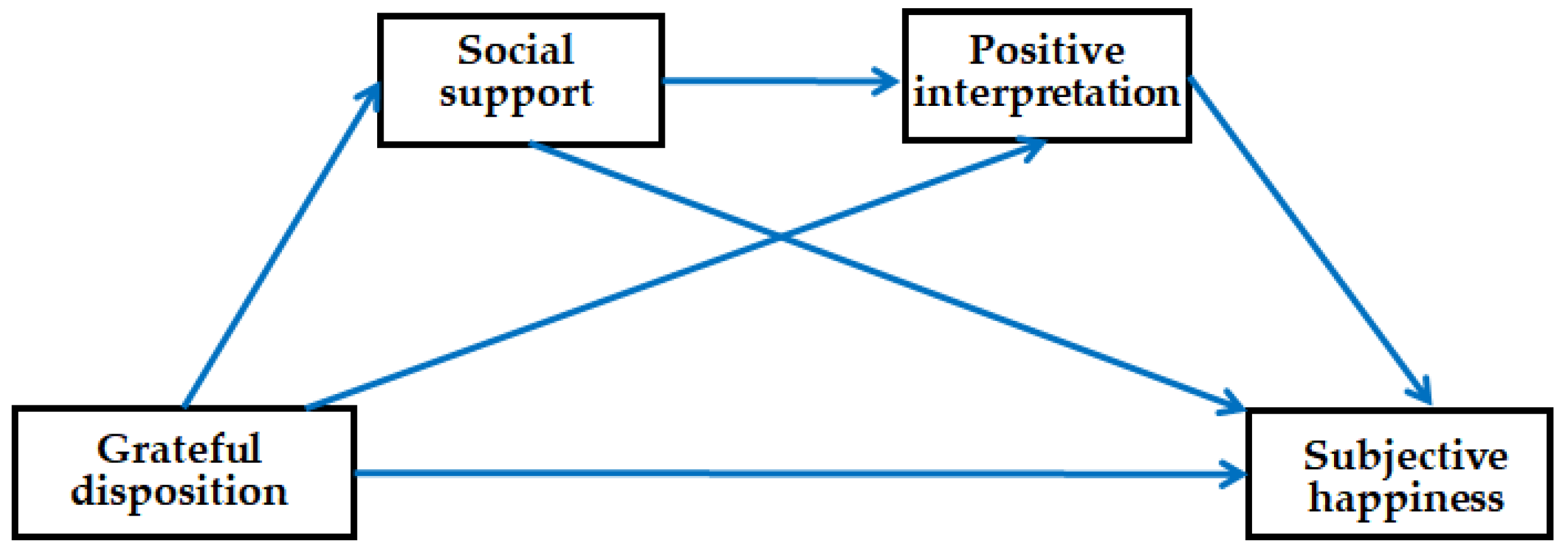

2.1. Research Design and Hypothesis

2.2. Participants

2.3. Participants’ Characteristics

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Instruments

2.5.1. Gratitude Questionnaire-6

2.5.2. Positive Interpretation Questionnaire

2.5.3. Scale for Social Support

2.5.4. Subjective Happiness Scale

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Relationship between Variables Involved in Subjective Happiness of Young Adults

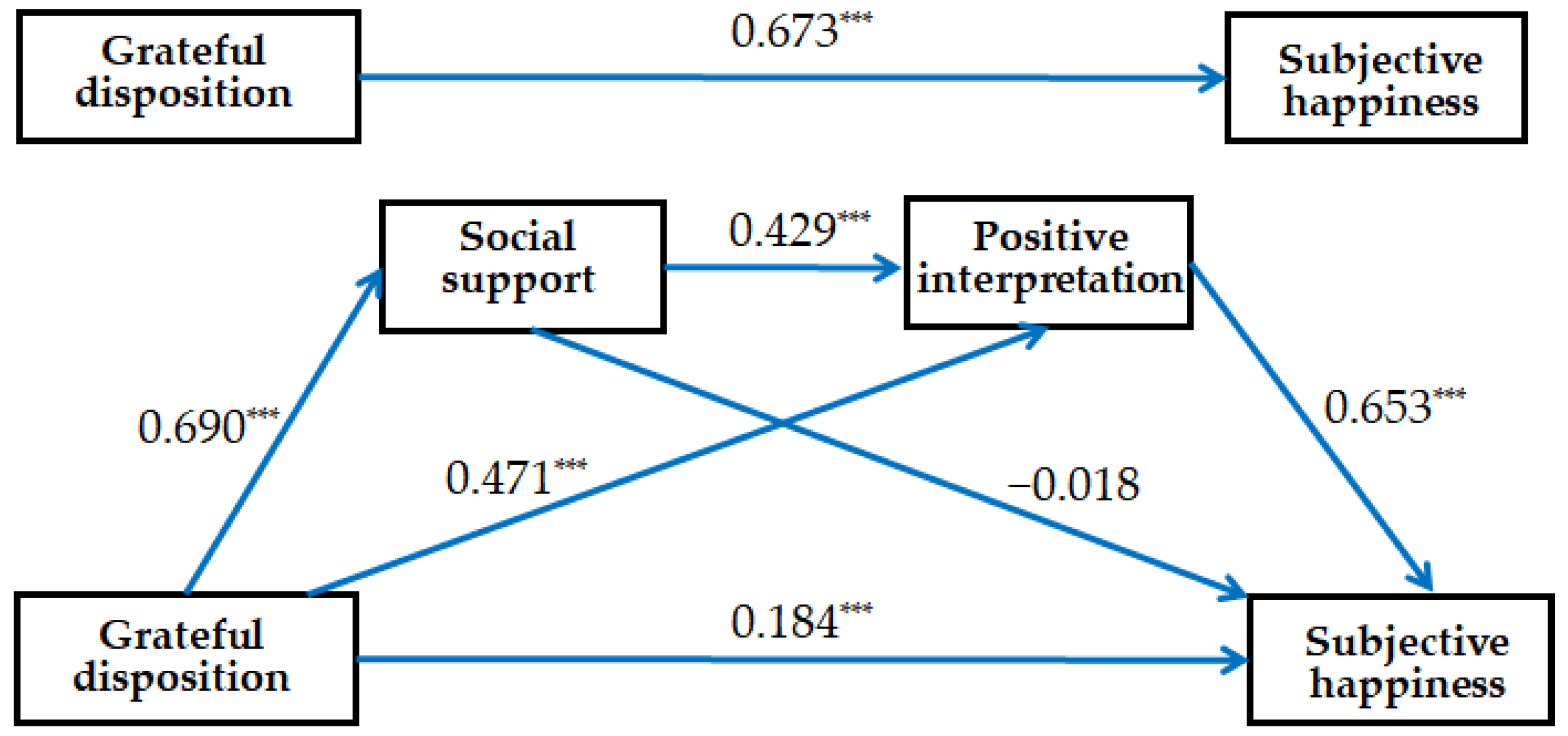

3.2. Verification of the Double Mediation Model for the Subjective Happiness of Young Adults

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| MZ | Millennials and Generation Z |

| GQ-6 | Gratitude Questionnaire-6 |

| SHS | Subjective Happiness Scale |

| IRB | institutional review board |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| VIF | variance inflation factor |

| LLCI | lower level for confidence interval |

| ULCI | upper level for confidence interval |

References

- Levinson, D.J. The mid-life transition: A period in adult psychosocial development. Psychiatry 1977, 40, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matud, M.P.; Díaz, A.; Bethencourt, J.M.; Ibáñez, I. Stress and psychological distress in emerging adulthood: A gender analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovi, M. The lasting well-Being effects of early adulthood macroeconomic crises. Rev. Income Wealth. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.J.; Jung, H.H.; Lim, H.; Kim, S.C. Lifestyle, health status and socioeconomic factors associated with depressive symptoms in Korean young adults: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017. Korean J. Fam. Pract. 2021, 11, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y. The effect of MZ generation characteristics on need solving and satisfaction. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2012, 34, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Emmons, R.A.; Tsang, J. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P.C. Gratitude and subjective well-being. In The Psychology of Gratitude; Emmons, R.A., McCullough, M.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: London, England, 2004; pp. 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkozei, A.; Smith, R.; Killgore, W.D.S. Gratitude and subjective well-being: A proposal of two causal frameworks. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1519–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froh, J.J.; Yurkewicz, C.; Kashdan, T.B. Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J. Gratitude and subjective well-being among Koreans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unanue, W.; Gomez, M.M.E.; Cortez, D.A.; Bravo, D.; Araya-Véliz, C.; Unanue, J.; Van Den Broeck, A. The reciprocal relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction: Evidence from two longitudinal field studies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P.C.; Frederick, M.; Dodson, W.A. Gratitude and happiness: The causes and consequences of gratitude. In Happiness and Wellness: Biopsychosocial and Anthropological Perspectives; Irtelli, F., Gabrielli, F., Eds.; Internet; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, L.F.; Pellanda, L.C.; Reppold, C.T. Positive psychology and gratitude interventions: A randomized clinical trial. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P.C.; Woodward, K.; Stone, T.; Kolts, R.L. Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude and relationships with subjective well-being. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2003, 31, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, L.; Vehreschild, V.; Renner, K.H. Effectiveness of two cognitive interventions promoting happiness with video-based online instructions. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzynska-Tatjewska, B.; Stolarski, M. Leaving past adversities behind: Gratitude intervention compensates for the undesirable effects of past time perspectives on negative affect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, F.B. Savoring Beliefs Inventory (SBI): A scale for measuring beliefs about savouring. J. Ment. Health 2003, 12, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujitani, T.; Ohara, K.; Kouda, K.; Mase, T.; Miyawaki, C.; Momoi, K.; Okita, Y.; Furutani, M.; Nakamura, H. Association of social support with gratitude and sense of coherence in Japanese young women: A cross-sectional study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2017, 10, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ati, M.R.S.; Matulessy, A.; Rochim, M.F. The relationship between gratitude and social support with the stress of parents who have children in need of special. J. Child Dev. Stud. 2018, 3, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Maltby, J.; Gillett, R.; Linley, P.A.; Joseph, S. The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. J. Res. Pers. 2008, 42, 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deichert, N.T.; Fekete, E.M.; Craven, M. Gratitude enhances the beneficial effects of social support on psychological well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 16, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Yin, R. Social support and hope mediate the relationship between gratitude and depression among front-line medical staff during the pandemic of COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 623873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rash, J.A.; Matsuba, M.K.; Prkachin, K.M. Gratitude and well-being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2011, 3, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakey, B. Perceived social support and happiness: The role of personality and relational processes. In Oxford Handbook of Happiness; Boniwell, I., David, S.A., Ayers, A.C., Eds.; Online Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeini, B.; Barati, M.; Farhadian, M.; Ara, M.H. The association between social support and happiness among elderly in Iran. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2018, 39, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalino, L.I.; Algoe, S.B.; Fredrickson, B.L. Prioritizing positivity: An effective approach to pursuing happiness? Emotion 2014, 14, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.J.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, H.S. Validation of the Korean version of Gratitude Questionnaire. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, K.; Lee, H.; Kim, K.; Moon, T. Development and standardization of SU Mental Health Test; Sahmyook University: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson, R.D.; Olekalns, M.; Erwin, P.J. Affectivity, organizational stressors, and absenteeism: A causal model of burnout and its consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 1998, 52, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, Y. The effect of Job Stress of Regional Government Employees on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: Focused on Adjustment Prevention Solution Effects according to Social Support. Master’s Thesis, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Lepper, H.S. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Ind. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. The Relationship between Life Satisfaction/Life Satisfaction Expectancy and Stress/Well-Being: An Application of Motivational States Theory. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 325–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D. Is gratitude a moral virtue? Philos. Stud. 2015, 172, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Lyubomirsky, S. How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. J. Posit. Psychol. 2006, 1, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Males Femals | 191 198 | 49.1 50.9 |

| Age group | 19 or 20s 30s | 205 194 | 52.7 47.3 |

| Educational qualification | High school College Graduate school | 80 279 30 | 20.6 71.7 7.7 |

| Marital status | Single Married Divorced | 290 97 2 | 74.6 24.9 0.5 |

| Residence type | Living alone Living with other(s) | 91 298 | 23.4 76.6 |

| Religion | Having a religion Having no religion | 271 118 | 69.7 30.3 |

| Occupation | Employed Unemployed | 291 98 | 74.8 25.2 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Grateful disposition | 1 | |||

| 2. Social support | 0.690 *** | 1 | ||

| 3. Positive interpretation | 0.767 *** | 0.754 *** | 1 | |

| 4. Subjective happiness | 0.673 *** | 0.601 *** | 0.781 *** | 1 |

| M | 28.98 | 27.87 | 20.86 | 17.48 |

| SD | 6.95 | 6.15 | 5.23 | 5.18 |

| Skewness | −0.10 | −0.08 | −0.29 | −0.28 |

| Kurtosis | −0.32 | −0.25 | −0.29 | −0.26 |

| Variables | B | S.E. | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediating Variable Model (Outcome Variable: Social support) | |||||

| Constant | 10.212 | 0.969 | 10.53 *** | 8.3061 | 12.1181 |

| Grateful disposition | 0.609 | 0.033 | 18.73 *** | 0.5455 | 0.6734 |

| Mediating Variable Model (Outcome Variable: Positive interpretation) | |||||

| Constant | 0.417 | 0.726 | 0.58 | −1.0098 | 1.8438 |

| Grateful disposition | 0.354 | 0.030 | 11.94 *** | 0.2958 | 0.4124 |

| Social support | 0.365 | 0.034 | 10.89 *** | 0.2994 | 0.4313 |

| Dependent Variable Model (Outcome Variable: Subjective happiness) | |||||

| Constant | 0.433 | 0.788 | 0.55 | −1.1165 | 1.9828 |

| Grateful disposition | 0.137 | 0.038 | 3.64 *** | 0.0629 | 0.2110 |

| Social support | −0.015 | 0.042 | −0.37 | −0.0972 | 0.0666 |

| Positive interpretation | 0.647 | 0.055 | 11.71 *** | 0.5385 | 0.7558 |

| Path | Effect | S.E | BC 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effect | 0.364 | 0.041 | 0.2870~0.4475 |

| Ind 1: A → B → C | −0.009 | 0.031 | −0.0693~0.0508 |

| Ind 2: A → C → D | 0.229 | 0.037 | 0.1616~0.3072 |

| Ind 3: A → B → C → D | 0.144 | 0.020 | 0.1069~0.1838 |

| Ind 1/Ind 2 | −0.239 | 0.055 | −0.3467~−0.1299 |

| Ind 1/Ind 3 | −0.153 | 0.040 | −0.2322~−0.0753 |

| Ind 2/Ind 3 | 0.085 | 0.042 | 0.0089~0.1745 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, J.-S.; Suh, K.-H. Relationship between Grateful Disposition and Subjective Happiness of Korean Young Adults: Focused on Double Mediating Effect of Social Support and Positive Interpretation. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040287

An J-S, Suh K-H. Relationship between Grateful Disposition and Subjective Happiness of Korean Young Adults: Focused on Double Mediating Effect of Social Support and Positive Interpretation. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(4):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040287

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Jae-Sun, and Kyung-Hyun Suh. 2023. "Relationship between Grateful Disposition and Subjective Happiness of Korean Young Adults: Focused on Double Mediating Effect of Social Support and Positive Interpretation" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 4: 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040287

APA StyleAn, J.-S., & Suh, K.-H. (2023). Relationship between Grateful Disposition and Subjective Happiness of Korean Young Adults: Focused on Double Mediating Effect of Social Support and Positive Interpretation. Behavioral Sciences, 13(4), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040287