How Can Restaurant Companies Effectively Deliver CSR Efforts to Consumers on Social Media?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Source Credibility

2.2. Brand Trust and Brand Affect

2.3. Research Hypotheses

3. Experiment 1

3.1. Method

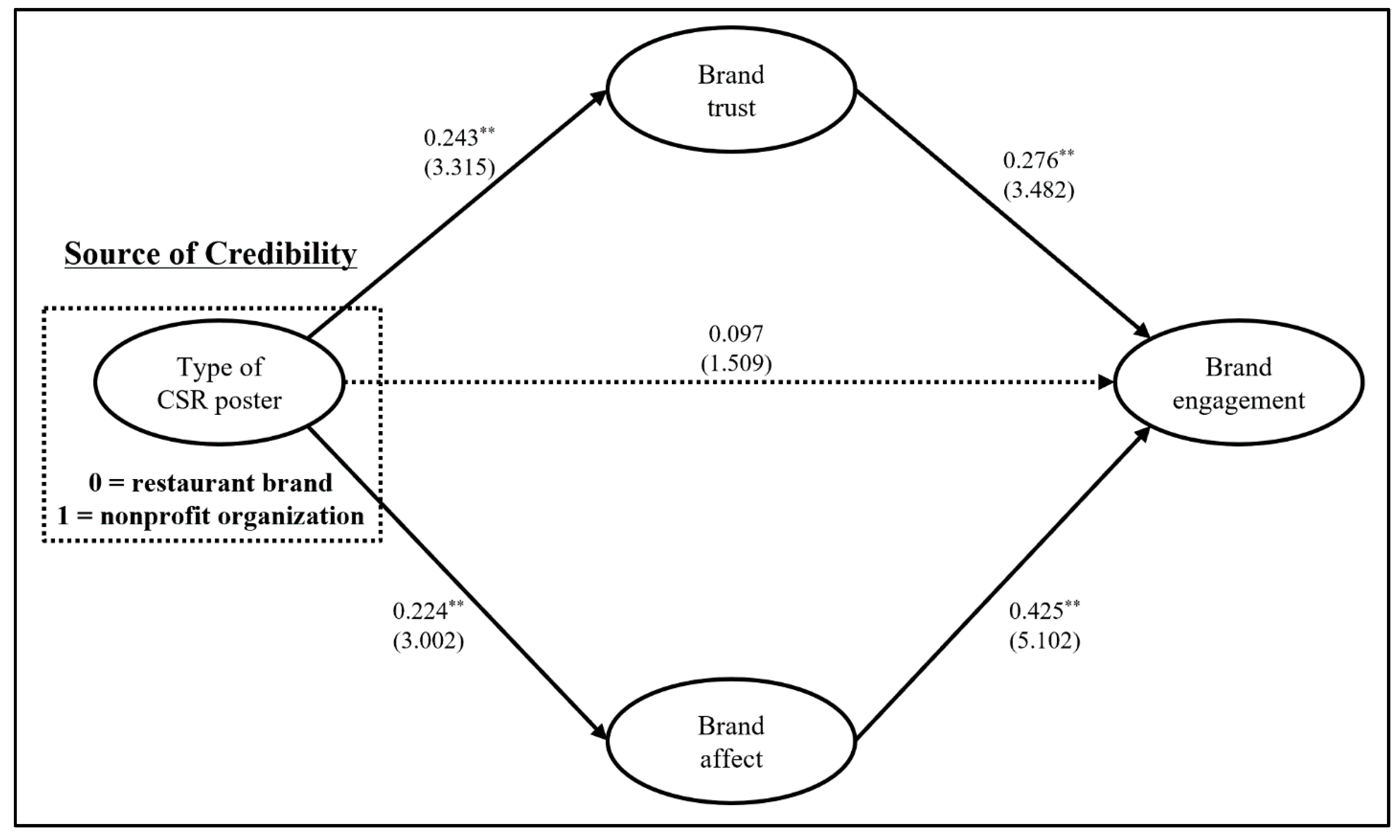

3.2. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holcomb, J.L.; Upchurch, R.S.; Okumus, F. Corporate social responsibility: What are top hotel companies reporting? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Wong, I.A.; Huang, G.I. The coevolutionary process of restaurant CSR in the time of mega disruption. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasruddin, E.; Bustami, R. The Yin and Yang of CSR ethical branding. Asian Acad. Manag. J. Account. Financ. 2007, 12, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Song, B. Corporate ethical branding on YouTube: CSR communication strategies and brand anthro-pomorphism. J. Interact. Advert. 2017, 17, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, D.Z.; Erlandson, J. Corporate social responsibility website representations: A longitudinal study of internal and external self-presentations. J. Mark. Commun. 2008, 14, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.; Tao, C.-W.; Slevitch, L. Restaurant chain’s corporate social responsibility messages on social networking sites: The role of social distance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 85, 102429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, F.; Castelló, I.; Morsing, M. The construction of corporate social responsibility in network societies: A communication view. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhouti, S.; Johnson, C.M.; Holloway, B.B. Corporate social responsibility authenticity: Investigating its antecedents and outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do Consumers Expect Companies to be Socially Responsible? The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Buying Behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarmeas, D.; Leonidou, C.N. When consumers doubt, Watch out! The role of CSR skepticism. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1831–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Maximizing Business Returns to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of CSR Communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J.L.; LaForge, R.W.; Goolsby, J.R. Personal communication in marketing: An examination of self-interest contingency relationships. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gurhan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trust-worthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Lafferty, B.A.; Newell, S.J. The Impact of Corporate Credibility and Celebrity Credibility on Consumer Reaction to Advertisements and Brands. J. Advert. 2000, 29, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Stepchenkova, S. Corporate social responsibility authenticity from the perspective of restaurant consumers. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 1140–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M. Rise of social media influencers as a new marketing channel: Focusing on the roles of psychological well-being and perceived social responsibility among consumers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Weiss, W. The Influence of Source Credibility on Communication Effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 1951, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P.B.; Wilson, D.W.; Haig, W.L. A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words: Source Credibility Theory Applied to Logo and Website Design for Heightened Credibility and Consumer Trust. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2013, 30, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, M.M.; Brubaker, P. Examining how image restoration strategy impacts perceptions of corporate social responsibility, organization-public relationships, and source credibility. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2010, 15, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groza, M.D.; Pronschinske, M.R.; Walker, M. Perceived Organizational Motives and Consumer Responses to Proactive and Reactive CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpan, L.M.; Varner, I.I. When in Rome? The Effects of Spokesperson Ethnicity on Audience Evaluation of Crisis Communication. J. Bus. Commun. 2002, 39, 314–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.; Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza, V. What drives CSR communication effectiveness on social media? A process-based theoretical framework and research agenda. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 41, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Zhang, W.; Abitbol, A. What makes CSR communication lead to CSR participation? Testing the mediating effects of CSR associations, CSR credibility, and organization–public relationships. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.R.; Laroche, M.; Richard, M.-O. The roles of brand community and community engagement in building brand trust on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Zaltman, G.; Deshpande, R. Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J.P.; Bower, G.H. Mood effects on person-perception judgments. Emot. Soc. Psychol. Essent. Read. 2001, 53, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Kim, J. Effects of brand personality on brand trust and brand affect. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, R.B. Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. Am. Psychol. 1980, 35, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I.; Rahman, Z.; Pérez, A. The sharing economy: The influence of perceived corporate social responsibility on brand commitment. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 30, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szykman, L.R.; Bloom, P.N.; Blazing, J. Does Corporate Sponsorship of a Socially-Oriented Message Make a Difference? An Investigation of the Effects of Sponsorship Identity on Responses to an Anti-Drinking and Driving Message. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, C.J.; Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Reimer, T.; Benkenstein, M.; Choi, B.; Kim, M.; Savas, S.; Berné-Manero, C.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M.; Ramo-Sáez, P.; et al. Achieving Marketing Objectives through Social Sponsorships. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Habibi, M.R.; Richard, M.-O.; Sankaranarayanan, R. The effects of social media based brand communities on brand community markers, value creation practices, brand trust and brand loyalty. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1755–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.G. Trust and the appraisal process in close relationships. Adv. Pers. Relatsh. Res. Annu. 1991, 2, 57–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bögel, P.M. Processing of CSR communication: Insights from the ELM. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2015, 20, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, L. Communicating CSR to consumers: An empirical study. In Strategic CSR Communication; Djøf Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006; pp. 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Buhmester, M.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S.D. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.D. Validating a Scale for the Measurement of Credibility: A Covariance Structure Modeling Approach. J. Q. 1994, 71, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Hwang, Y.; Kim, S.; Biocca, F.A. How social media engagement leads to sports channel loyalty: Mediating roles of social presence and channel commitment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 46, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Baek, T.H. I’ll follow the fun: The extended investment model of social media influencers. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 74, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Talwar, S.; Madanaguli, A.; Srivastava, S.; Dhir, A. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and hospitality sector: Charting new frontiers for restaurant businesses. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; De Los Salmones, M.D.M.G. CSR communication and media channel choice in the hospitality and tourism industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 45, 101066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, S.; Ferns, B.H.; Countryman, C.C. Pride or empathy? Exploring effective CSR communication strategies on social media. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2989–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Shamim, A.; Park, J. Impacts of cruise industry corporate social responsibility reputation on customers’ loyalty: Mediating role of trust and identification. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 92, 102706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketron, S.; Naletelich, K. Victim or beggar? Anthropomorphic messengers and the savior effect in consumer sustainability behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 96, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acunto, D.; Tuan, A.; Dalli, D.; Viglia, G.; Okumus, F. Do consumers care about CSR in their online reviews? An empirical analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs and Operationalization | Items | Factor Loading | Critical Ratio | AVE | CCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand trust | I trust this restaurant brand. | 0.759 | Fixed | 0.591 | 0.848 |

| I rely on this restaurant brand. | 0.884 | 12.618 | |||

| This is an honest restaurant brand. | 0.850 | 12.287 | |||

| This restaurant brand is safe. | 0.532 | 7.437 | |||

| Brand affect | This restaurant brand makes me happy. | 0.809 | Fixed | 0.660 | 0.851 |

| This restaurant brand gives me pleasure. | 0.874 | 11.715 | |||

| I feel good when I think about this restaurant brand. | 0.651 | 9.337 | |||

| Brand engagement | I will share this restaurant brand’s CSR-related video or photos on my social media. | 0.800 | Fixed | 0.686 | 0.867 |

| I will use trending words such as hashtags for this restaurant brand’s CSR activities while using social media. | 0.900 | 13.354 | |||

| I will share my opinions about this restaurant brand’s CSR activities with other users of this brand. | 0.779 | 11.913 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.-M.; Kim, M. How Can Restaurant Companies Effectively Deliver CSR Efforts to Consumers on Social Media? Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030211

Lee S-M, Kim M. How Can Restaurant Companies Effectively Deliver CSR Efforts to Consumers on Social Media? Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(3):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030211

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sae-Mi, and Minseong Kim. 2023. "How Can Restaurant Companies Effectively Deliver CSR Efforts to Consumers on Social Media?" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 3: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030211

APA StyleLee, S.-M., & Kim, M. (2023). How Can Restaurant Companies Effectively Deliver CSR Efforts to Consumers on Social Media? Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13030211