Psychological Factors Explaining the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Mental Health: The Role of Meaning, Beliefs, and Perceptions of Vulnerability and Mortality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Measures

- Core Belief Inventory (CBI) [39]. A brief measure of the effect of stressful experiences on an individual’s assumptive world or, in other words, a measure of violation of core beliefs. The CBI consists of nine items focusing on religious and spiritual beliefs, human nature, relationships with other people, meaning of life, and personal strengths and weaknesses. The respondents indicate the extent to which the stressful experience (in our case, the pandemic) led them to seriously examine their core beliefs. Responses are given on a six-point scale ranging from “not at all” (0) to “to a very great degree” (5). The total score is computed as the mean of individual item scores, and higher values indicate a greater degree of core beliefs violation. In this study, CBI showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.90);

- Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale—Short Form (ISLES-SF) [54]. A brief measure of an individual’s ability to make sense of stressful events. It assesses the degree of disrupted meaning making following a specific event, in the present case, the pandemic. The ISLES-SF consists of six items, and participants express their degree of agreement on a five-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (5). The total score is computed as the sum of item scores, and lower values indicate a greater disruption in meaning making ability. In this study, ISLES-SF showed good internal consistency (α = 0.88);

- Vulnerability. Participants reported their agreement with the statement “This pandemic made me feel vulnerable and fragile” using a 6-point scale (from 0 = “not at all” to 5 = “to a very high degree”);

- Mortality. Participants reported their agreement with the statement, “This pandemic made me think more about my own death” (from 0 = “not at all” to 5 = “to a very high degree”).

- Four-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4) [55]. An ultra-brief measure (four items) of anxiety and depression problems experienced over the last two weeks. Respondents indicate the frequency of the proposed feelings on a 4-point scale ranging from “not at all” (0) to “nearly every day” (3). The total score is determined as the sum of item scores and indicates the severity of reported symptoms. In this study, PHQ-4 showed good internal consistency (α = 0.86);

- Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS) [20]. A brief mental health screener (five items) designed to quickly and accurately identify individuals functionally impaired by their fear and anxiety over the coronavirus. Respondents reported the frequency of given situations on a 4-point scale ranging from “not at all” (0) to “nearly every day over the last two weeks” (3). The total score is computed as the sum of item scores and indicates the degree of coronavirus dysfunctional anxiety experienced over the last two weeks. In this study, CAS showed suitable internal consistency (α = 0.86);

- General Population—Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (GP-CORE) [56]. A non-clinical 14-item self-report measure of wellbeing, psychological problems, and functioning for the general population (GP), derived from the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (CORE-OM). For each item, the respondents rate themselves with reference to the last week on a 5-point scale ranging from “not at all” (0) to “most or all of the time” (4). A single overall score is created by calculating the mean score over the 14 items, where higher values indicate lower degrees of wellbeing. In this study, GP-CORE showed good internal consistency (α = 0.83);

- Profile Of Mood States (POMS) [57]. A self-report mood adjective checklist in which each adjective is scored from 0 (absent) to 4 (very much) based on how well each item describes the respondent’s mood during the previous week. The 58 items are grouped into six subscales: tension, anger, fatigue, depression, confusion, and vigor. An overall measure of respondents’ mood can be calculated by subtracting the vigor score from the sum of the other scales’ scores. In this study, POMS showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.98).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Multiple Regressions

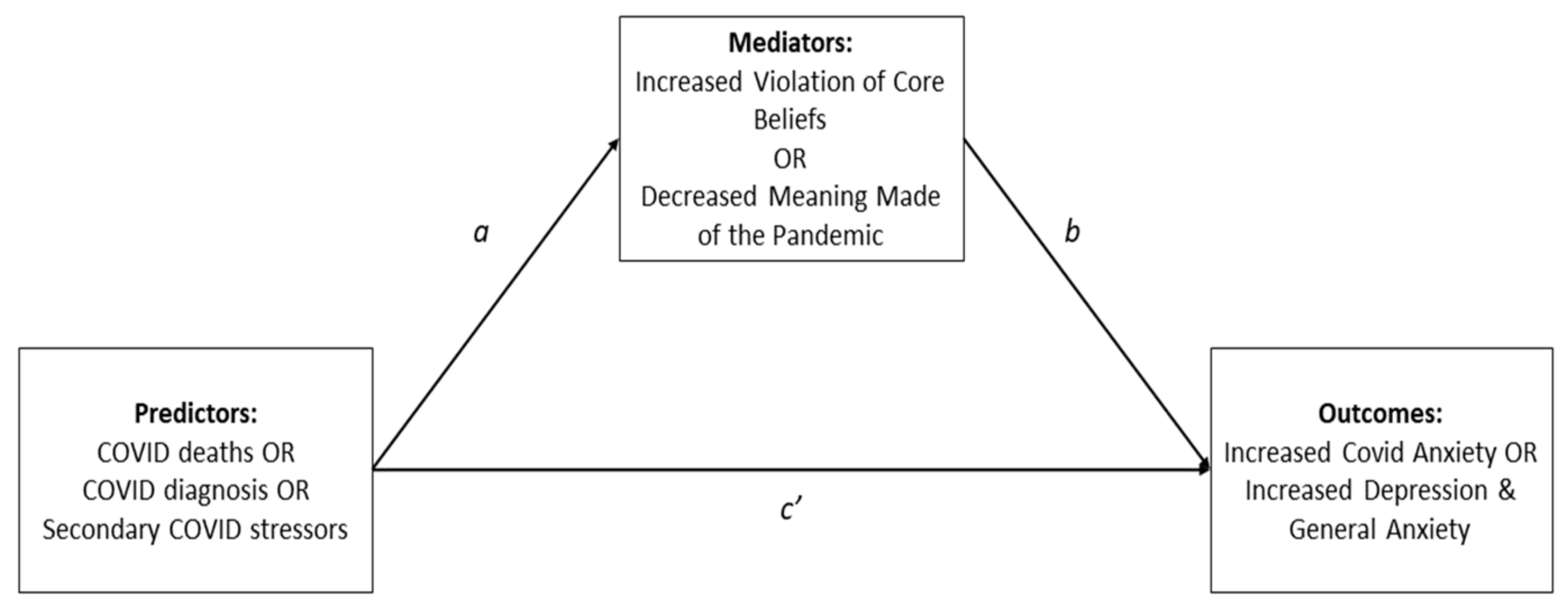

3.3. Multiple Mediation

- Violation of core beliefs (CBI) mediated the effects of several indirect COVID-19 stressors on post-pandemic mental health levels. It mediated the effects of unemployment and childcare loss on CAS and POMS, the effects of leaving home for work on POMS, the effects of exposure to COVID-related deaths on CAS, and the effects of economic difficulties on all four outcomes;

- Perceived vulnerability mediated the effects of economic difficulties on PHQ-4, GP-CORE, and POMS but not on CAS;

- Perception of mortality mediated the effects of one direct COVID-19 stressor (exposure to COVID-related deaths) on coronavirus anxiety level (CAS);

- Disrupted meaning making (ISLES-SF) about the pandemic did not significantly mediate the effects of any predictor on the outcomes;

- Exposure to COVID-related deaths was the only predictor to have a significant direct effect on one of the post-pandemic mental health measures, the coronavirus anxiety level (CAS).

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Age | Gender | MS Single | MS Relationship | MS Cohabiting | MS Divorced or Widowed | Children | Caretaker Role | Physical Illness | Mental Illness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||||

| Gender | 0.16 *** | |||||||||

| MS single | −0.29 *** | −0.02 | ||||||||

| MS relationship | −0.27 *** | 0.01 | −0.11 ** | |||||||

| MS cohabiting | 0.24 *** | 0.03 | −0.62 *** | −0.42 *** | ||||||

| MS divorced/widowed | 0.21 *** | −0.04 | −0.13 *** | −0.09 * | −0.48 *** | |||||

| Children | −0.11 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.25 *** | −0.15 *** | 0.30 *** | −0.05 | ||||

| Caretaker role | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.17 *** | −0.01 | −0.11 ** | −0.01 | −0.05 | |||

| Physical illness | 0.47 *** | 0.09 * | −0.06 | −0.10 * | 0.05 | 0.08 * | −0.19 *** | −0.02 | ||

| Mental illness | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.13 ** | |

| COVID diagnosis | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.08 * | −0.05 | 0.08 * | 0.02 | 0.12 ** | −0.04 | −0.09 * | 0.08 * |

| COVID death | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Job loss or reduction | −0.17 *** | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.11 ** | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 * | −0.01 | −0.08 * | 0.10 * |

| Economic difficulties | −0.12 ** | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.11 ** | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.09 * |

| Childcare loss | −0.17 *** | −0.08 * | −0.13 *** | 0.00 | 0.11 ** | −0.02 | 0.44 *** | −0.02 | −0.14 *** | 0.08 * |

| Working from home | −0.29 *** | −0.09 * | 0.07 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.15 *** | 0.06 | −0.17 *** | 0.09 * |

| Leaving home to work | −0.22 *** | −0.06+ | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.17 *** | −0.02 | −0.16 *** | 0.09 * |

| Working w/COVID patients | −0.08 * | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.08 * | −0.03 |

| Confinement | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| CBI | −0.22 *** | −0.24 *** | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.08 * | 0.11 ** |

| ISLES | −0.08 * | −0.09 * | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Vulnerability | −0.16 *** | −0.21 *** | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.12 ** |

| Mortality | 0.03 | −0.15 *** | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.10 ** | 0.08 * | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| CAS | 0.00 | −0.17 *** | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.08 * | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.33 *** |

| PHQ4 | −0.26 *** | −0.20 *** | 0.09 * | 0.07 | −0.10 * | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.24 *** |

| GP-CORE | −0.19 *** | −0.11 ** | 0.13 *** | 0.03 | −0.12 ** | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.25 *** |

| POMS | −0.24 *** | −0.14 *** | 0.12 ** | 0.05 | −0.11 ** | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.27 *** |

| COVID Diagnosis | COVID Death | Job Loss Or Reduction | Economic Difficulties | Childcare Loss | Working from Home | Leaving Home to Work | Working with COVID Patients | Confinement | ||

| COVID diagnosis | ||||||||||

| COVID death | 0.00 | |||||||||

| Job loss or reduction | 0.08 * | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Economic difficulties | 0.11 ** | 0.01 | 0.84 *** | |||||||

| Childcare loss | 0.12 ** | −0.02 | 0.60 *** | 0.58 *** | ||||||

| Working from home | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.44 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.46 *** | |||||

| Leaving home to work | 0.09 * | 0.00 | 0.54 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.55 *** | 0.51 *** | ||||

| Working with COVID patients | 0.01 | 0.08 * | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.10 ** | |||

| Confinement | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.10 ** | 0.24 *** | 0.07 | −0.06 | ||

| CBI | 0.11 ** | 0.09 * | 0.23 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.11 ** | 0.20 *** | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| ISLES | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.19 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.04 | 0.11 ** | 0.00 | −0.05 | |

| Vulnerability | 0.09 * | 0.11 ** | 0.10 * | 0.11 ** | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 ** | −0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Mortality | 0.09 * | 0.14 *** | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| CAS | 0.06 | 0.13 *** | 0.11 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.05 | |

| PHQ4 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.10 ** | 0.07 | 0.09 * | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |

| GP-CORE | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.10 * | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.02 | |

| POMS | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.09 * | 0.14 *** | 0.09 * | 0.09 * | 0.10 * | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| CBI | ISLES | Vulnerability | Mortality | CAS | PHQ-4 | GP-CORE | ||||

| CBI | ||||||||||

| ISLES | 0.29 *** | |||||||||

| Vulnerability | 0.64 *** | 0.24 *** | ||||||||

| Mortality | 0.51 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.60 *** | |||||||

| CAS | 0.40 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.37 *** | ||||||

| PHQ4 | 0.45 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.46 *** | |||||

| GP-CORE | 0.43 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.77 *** | ||||

| POMS | 0.46 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.80 *** | 0.84 *** | |||

References

- Milman, E.; Lee, S.A.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Mathis, A.A.; Jobe, M.C. Modeling pandemic depression and anxiety: The mediational role of core beliefs and meaning making. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2020, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altig, D.; Baker, S.; Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Bunn, P.; Chen, S.; Davis, S.J.; Leather, J.; Meyer, B.; Mihaylov, E.; et al. Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I.; Leung, G.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Matsoso, M.P.; Ihekweazu, C.; Abbasi, K. COVID-19: How a virus is turning the world upside down. BMJ 2020, 369, m1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Nayar, K.R. COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, F.; Oshvandi, K.; Shamsaei, F.; Cheraghi, F.; Khodaveisi, M.; Bijani, M. The mental health crises of the families of COVID-19 victims: A qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venuleo, C.; Marinaci, T.; Gennaro, A.; Castiglioni, M.; Caldiroli, C.L. The institutional management of the COVID-19 crisis in Italy: A qualitative study on the socio-cultural context underpinning the citizens’ evaluation. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, H.X.; Li, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cheung, T.; Wu, X.; Xiang, Y.T. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitude toward crisis mental health services among clinically stable patients with COVID-19 in China. Psychol. Med. 2020, 51, 1052–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.K.T.; Carvalho, P.M.M.; Lima, I.A.A.S.; Nunes, J.V.A.O.; Saraiva, J.S.; De Souza, R.I.; Da Silva, C.G.L.; Neto, M.L.R. The emotional impact of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new Coronavirus disease). Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prime, H.; Wade, M.; Browne, D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmits, E.; Glowacz, F. Changes in Alcohol Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact of the Lockdown Conditions and Mental Health Factors. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, H.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, S.; Du, Q.; Jiang, T.; Du, B. The differential psychological distress of populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallonardo, V.; Sampogna, G.; Del Vecchio, V.; Luciano, M.; Albert, U.; Carmassi, C.; Carrà, G.; Cirulli, F.; Dell’Osso, B.; Nanni, M.G.; et al. The Impact of Quarantine and Physical Distancing Following COVID-19 on Mental Health: Study Protocol of a Multicentric Italian Population Trial. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, C.; Yang, B.X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Lai, J.; Ma, X.; et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.C.; Park, Y.C. Mental Health Care Measures in Response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2020, 17, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigemura, J.; Ursano, R.J.; Morganstein, J.C.; Kurosawa, M.; Benedek, D.M. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, E.; Levine, L.; Kay, A. Mental health stressors in Israel during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuleo, C.; Gelo, O.C.G.; Salvatore, S. Fear, Affective Semiosis, and Management of the Pandemic Crisis: COVID-19 as Semiotic Vaccine? Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 17, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenburg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic. N. Eng. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; Overall, N.C. Implications of social isolation, separation, and loss during the COVID-19 pandemic for couples’ relationships. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 43, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallesen, P. Decline in Rate of Divorce and Separation Filings in Denmark in 2020 Compared with Previous Years. Socius 2021, 7, 23780231211009991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.E.; Allen, K.R.; Smith, J.Z. Divorced and separated parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam. Process 2021, 60, 866–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.; Thakar, R. Domestic violence: An invisible pandemic. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 24, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourti, A.; Stavridou, A.; Panagouli, E.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Spiliopoulou, C.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A. Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 15248380211038690, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, J.K.; Peña, L.D.; Anurudran, A.; Pai, A. “Are you safe to talk?”: Perspectives of Service Providers on Experiences of Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Fam. Violence 2022, 38, 215–225, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquero, A.R.; Jennings, W.G.; Jemison, E.; Kaukinen, C.; Knaul, F.M. Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic—Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crim. Justice 2021, 74, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.M.; Doom, J.R.; Lechuga-Peña, S.; Watamura, S.E.; Koppels, T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 110 Pt 2, 104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciciurkaite, G.; Marquez-Velarde, G.; Brown, R.L. Stressors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, disability, and mental health: Considerations from the Intermountain West. Stress Health 2022, 38, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorillo, A.; Gorwood, P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, E.; Lee, S.A.; Neimeyer, R.A. Social isolation as a means of reducing dysfunctional coronavirus anxiety and increasing psychoneuroimmunity. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyah, Y.; Benjelloun, M.; Lairini, S.; Lahrichi, A. COVID-19 Impact on Public Health, Environment, Human Psychology, Global Socioeconomy, and Education. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 5578284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, M.; Zimmerman, L.; Azevedo, K.J.; Ruzek, J.I.; Gala, S.; Abdel Magid, H.S.; Cohen, N.; Walser, R.; Mahtani, N.D.; Hoggatt, K.J.; et al. Addressing the mental health impact of COVID-19 through population health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 85, 102006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Toscano, M.; Vaqué-Alcázar, L.; Cattaneo, G.; Solana-Sánchez, J.; Bayes-Marin, I.; Abellaneda-Pérez, K.; Macià-Bros, D.; Mulet-Pons, L.; Portellano-Ortiz, C.; Fullana, M.A.; et al. Functional Brain Connectivity Prior to the COVID-19 Outbreak Moderates the Effects of Coping and Perceived Stress on Mental Health Changes: A First Year of COVID-19 Pandemic Follow-up Study. Biol. Psychiatry Cog. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2022. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, J.A.D.B.; Campos, L.A.; Martins, B.G.; Valadão Dias, F.; Ruano, R.; Maroco, J. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Individuals With and Without Mental Health Disorders. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 2435–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.C.; Cohodes, E.M.; Brieant, A.E.; McCauley, S.; Odriozola, P.; Zacharek, S.J.; Pierre, J.C.; Hodges, H.R.; Kribakaran, S.; Haberman, J.T.; et al. Associations between early-life stress exposure and internalizing symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Assessing the role of neurobehavioral mediators. Biol. Psychiatry Glob. Open Sci. 2022. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzebiński, J.; Cabański, M.; Czarnecka, J.Z. Reaction to the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Influence of Meaning in Life, Life Satisfaction, and Assumptions on World Orderliness and Positivity. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Kilmer, R.P.; Gil-Rivas, V.; Vishnevsky, T.; Danhauer, S.C. The Core Beliefs Inventory: A brief measure of disruption in the assumptive world. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currier, J.M.; Holland, J.M.; Coleman, R.A.; Neimeyer, R.A. Bereavement following violent death: An assault on life and meaning. In Perspectives on Violence and Violent Death; Stevenson, R.G., Cox, G.R., Eds.; Death, Value and Meaning Series; Baywood Publishing Co.: Amityville, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Currier, J.M.; Holland, J.M.; Neimeyer, R.A. Assumptive worldviews and problematic reactions to bereavement. J. Loss Trauma 2009, 14, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.M.; Currier, J.M.; Neimeyer, R.A. Meaning reconstruction in the first two years of bereavement: The role of sense-making and benefit-finding. Omega J. Death Dying 2006, 53, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoff-Bulman, R. Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: Applications of the schema construct. Soc. Cogn. 1989, 7, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, E.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Fitzpatrick, M.; MacKinnon, C.J.; Muis, K.R.; Cohen, S.R. Prolonged grief symptomatology following violent loss: The mediating role of meaning. Eur. Psychotraumatol. 2018, 8, 1503522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, E.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Fitzpatrick, M.; MacKinnon, C.J.; Muis, K.R.; Cohen, S.R. Prolonged grief and the disruption of meaning: Establishing a mediation model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: Development of a research program. Death Stud. 2019, 43, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Riley, K.E.; George, L.S.; Gutierrez, I.A.; Hale, A.E.; Cho, D.; Braun, T.D. Assessing disruptions in meaning: Development of the Global Meaning Violation Scale. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2016, 40, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Kennedy, M.C. Meaning violation and restoration following trauma: Conceptual overview and clinical implications. In Reconstructing Meaning after Trauma: Theory, Research, and Practice; Altmaier, E.M., Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzberg, S.S.; Janoff-Bulman, R. Grief and the search for meaning: Exploring the assumptive worlds of bereaved college students. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 10, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.A. The Psychology of Personal Constructs; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni, M.; Gaj, N. Fostering the Reconstruction of Meaning Among the General Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuleo, C.; Marinaci, T.; Gennaro, A.; Palmieri, A. The meaning of living in the time of COVID-19. A large sample narrative inquiry. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 577077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyszczynski, T.; Solomon, S.; Greenberg, J. Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 52, pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.M.; Currier, J.M.; Neimeyer, R.A. Validation of the Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale-short form in a bereaved sample. Death Stud. 2014, 38, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Connell, J.; Audin, K.; Sinclair, A.; Barkham, M. Rationale and development of a general population well-being measure: Psychometric status of the GP-CORE in a student sample. Br. J. Guid. Couns 2005, 33, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, D.M.; Lorr, M.; Droppleman, L.F. Manual for the Profile of Mood States; Educational and Industrial Testing Services: San Diego, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Benros, M.E.; Klein, R.S.; Vinkers, C.H. How COVID-19 shaped mental health: From infection to pandemic effects. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2027–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauhanen, L.; Wan Mohd Yunus, W.M.; Lempinen, L.; Peltonen, K.; Gyllenberg, D.; Mishina, K.; Gilbert, S.; Bastola, K.; Brown, J.S.; Sourander, A. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negri, A.; Andreoli, G.; Barazzetti, A.; Zamin, C.; Christian, C. Linguistic Markers of the Emotion Elaboration Surrounding the Confinement Period in the Italian Epicenter of COVID-19 Outbreak. Front. Psychology 2020, 11, 568281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.L. Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 257–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelen, P.A.; De Keijser, J.; Smid, G. Cognitive-behavioral variables mediate the impact of violent loss on post-loss psychopathology. Psychol. Trauma 2015, 7, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S. Narrative Therapy; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R.; Yalom, I.D. Existential psychotherapy. In Current Psychotherapies; Corsini, R.J., Wedding, D., Eds.; F E Peacock Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1989; pp. 363–402. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Constructivist Psychotherapy: Distinctive Features; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Correspondence with the deceased. In Techniques of Grief Therapy: Creative Practices for Counseling the Bereaved; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 259–261. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.K. Maps of Narrative Practice; Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Variables | |

|---|---|

| Education | Primary school = 33 (4.8%) Secondary school = 260 (38.2%) Post-secondary school = 387 (57.0%) |

| Marital status | Single = 97 (14.3%) In a relationship (not living together) = 48 (7.0%) In a relationship (living together) = 473 (69.6%) Divorced/widowed = 62 (9.1%) |

| Children in the house | None = 414 (60.9%) One = 109 (16.0%) Two = 127 (18.7%) Three = 26 (3.8%) Four = 4 (0.6%) |

| Caregiver role | 51 (7.5%) |

| Physical illness | 303 (44.6%) |

| Mental illness | 13 (1.9%) |

| Indirect COVID-19 Stressors | |

| Job loss or reduction | 336 (49.4%) |

| Economic difficulties | 361 (53.1%) |

| Childcare loss | 335 (49.3%) |

| Confinement | 637 (93.7%) |

| Working from home | 467 (68.7%) |

| Leaving home to work | 406 (59.7%) |

| Work with COVID patients | 30 (4.4%) |

| Direct COVID-19 Stressors | |

| COVID diagnosis | 85 (12.5%) |

| COVID death | None = 134 (19.7%) Acquaintances = 411 (60.4%) Significant others = 135 (19.8%) |

| Range | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pandemic-related psychological factors | ||

| CBI | 0; 5 | 2.26 (1.27) |

| ISLES-SF | 6; 30 | 19.08 (6.85) |

| Vulnerability | 0; 5 | 2.74 (1.67) |

| Mortality | 0; 5 | 2.36 (1.77) |

| Post-pandemic mental health measures | ||

| PHQ | 0; 12 | 3.97 (3.09) |

| CAS | 0; 19 | 1.38 (2.71) |

| GP-CORE | 0; 3.57 | 1.51 (0.6) |

| POMS | −29; 187 | 33.1 (41.35) |

| Outcome | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Demographics + Indirect stressors | Demographics + Indirect stressors + Direct stressors | Demographics + Indirect stressors + Direct stressors + Psychol. factors | |

| CAS | R2 = 0.139 | R2 = 0.144 | R2 = 0.156 ** | R2 = 0.288 *** |

| PHQ-4 | R2 = 0.144 | R2 = 0.145 | R2 = 0.147 | R2 = 0.327 *** |

| GP-CORE | R2 = 0.115 | R2 = 0.119 | R2 = 0.122 a | R2 = 0.298 *** |

| POMS | R2 = 0.132 | R2 = 0.140 * | R2 = 0.141 | R2 = 0.334 *** |

| Mean | R2 = 0.133 | R2 = 0.137 | R2 = 0.142 | R2 = 0.312 |

| Predictors | CAS | PHQ-4 | GP-CORE | POMS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (b) | p | Estimate (b) | p | Estimate (b) | p | Estimate (b) | p | |

| (Intercept) | −0.33 | 0.685 | 3.31 | <0.001 | 1.35 | <0.001 | 13.90 | 0.245 |

| Gender | −0.40 | 0.036 | −0.31 | 0.139 | 0.03 | 0.449 | 0.95 | 0.737 |

| Education | −0.26 | 0.100 | 0.16 | 0.360 | 0.02 | 0.562 | 3.53 | 0.138 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.355 | −0.04 | <0.001 | −0.01 | <0.001 | −0.40 | <0.001 |

| MS single a | 0.05 | 0.816 | 0.05 | 0.849 | 0.08 | 0.098 | 4.52 | 0.171 |

| MS relationship a | −0.15 | 0.587 | 0.07 | 0.814 | −0.06 | 0.379 | −0.88 | 0.834 |

| MS cohabiting a | −0.10 | 0.554 | −0.13 | 0.469 | −0.04 | 0.217 | −2.37 | 0.330 |

| Children | −0.06 | 0.625 | 0.11 | 0.373 | −0.01 | 0.819 | 1.03 | 0.545 |

| Caretaker role | 0.22 | 0.517 | 0.74 | 0.051 | 0.10 | 0.199 | 8.69 | 0.086 |

| Physical illness | 0.18 | 0.389 | 0.58 | 0.011 | 0.16 | 0.001 | 6.15 | 0.044 |

| Mental illness | 5.29 | <0.001 | 4.34 | <0.001 | 0.91 | <0.001 | 66.32 | <0.001 |

| Job loss or reduction | 0.02 | 0.944 | −0.79 | 0.044 | −0.20 | 0.011 | −12.09 | 0.021 |

| Economic difficulties | 0.10 | 0.764 | 0.67 | 0.074 | 0.15 | 0.044 | 12.38 | 0.013 |

| Childcare loss | 0.46 | 0.094 | 0.02 | 0.950 | 0.03 | 0.629 | 1.38 | 0.732 |

| Working from home | −0.14 | 0.579 | 0.02 | 0.956 | −0.02 | 0.778 | −1.52 | 0.678 |

| Leaving home to work | −0.54 | 0.027 | −0.32 | 0.232 | −0.03 | 0.523 | −1.48 | 0.677 |

| Confinement | 0.40 | 0.287 | −0.28 | 0.500 | −0.02 | 0.803 | −5.10 | 0.361 |

| Working with COVID patients | −0.05 | 0.915 | −0.21 | 0.668 | −0.10 | 0.284 | −0.61 | 0.926 |

| COVID diagnosis | −0.03 | 0.912 | 0.02 | 0.950 | 0.01 | 0.875 | −1.81 | 0.654 |

| COVID death | 0.32 | 0.025 | 0.04 | 0.815 | 0.01 | 0.816 | 0.51 | 0.810 |

| CBI | 0.50 | <0.001 | 0.47 | <0.001 | 0.10 | <0.001 | 7.26 | <0.001 |

| ISLES | −0.02 | 0.117 | −0.01 | 0.530 | −0.01 | 0.108 | −0.22 | 0.272 |

| Vulnerability | 0.05 | 0.529 | 0.58 | <0.001 | 0.08 | <0.001 | 7.43 | <0.001 |

| Mortality | 0.26 | <0.001 | −0.02 | 0.819 | 0.02 | 0.094 | −0.22 | 0.822 |

| Stressor | Outcome | Mediator | Controlled Direct Effect b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBI a | ISLES a | Vulnerability a | Mortality a | |||

| Job loss or reduction | CAS | 0.24 [0.11, 0.4] | 0.05 [0.00, 0.12] | 0.01 [−0.02, 0.04] | 0.05 [−0.02, 0.13] | 0.07 0.700 |

| Job loss or reduction | POMS | 3.22 [1.44, 5.5] | 0.55 [−0.35, 1.62] | 1.28 [−0.59, 3.25] | −0.02 [−0.56, 0.48] | −3.02 0.268 |

| Childcare loss | CAS | 0.16 [0.04, 0.31] | 0.06 [0.00, 0.14] | 0.01 [−0.02, 0.05] | 0.04 [−0.04, 0.13] | 0.19 0.341 |

| Childcare loss | POMS | 2.10 [0.55, 4.18] | 0.58 [−0.43, 1.70] | 1.35 [−0.80, 3.61] | −0.01 [−0.46, 0.43] | −0.65 0.828 |

| Economic difficulties | CAS | 0.28 [0.14, 0.45] | 0.05 [0.00, 0.11] | 0.01 [−0.02, 0.06] | 0.06 [−0.01, 0.14] | 0.11 0.544 |

| Economic difficulties | PHQ-4 | 0.24 [0.11, 0.39] | 0.02 [−0.05, 0.08] | 0.17 [0.02, 0.33] | 0.00 [−0.05, 0.04] | −0.11 0.579 |

| Economic difficulties | GP-CORE | 0.05 [0.02, 0.08] | 0.01 [0.00, 0.03] | 0.02 [0.00, 0.05] | 0.01 [0.00, 0.02] | −0.02 0.670 |

| Economic difficulties | POMS | 3.61 [1.67, 5.94] | 0.45 [−0.37, 1.43] | 2.16 [0.28, 4.34] | 0.00 [−0.54, 0.52] | 1.38 0.615 |

| Working from home | PHQ-4 | 0.03 [−0.05, 0.13] | 0.00 [−0.02, 0.02] | 0.07 [−0.09, 0.25] | 0.00 [−0.03, 0.03] | −0.20 0.367 |

| Working from home | POMS | 0.55 [−0.88, 2.18] | 0.04 [−0.30, 0.46] | 0.89 [−1.19, 3.13] | 0.01 [−0.34, 0.38] | −2.09 0.480 |

| Leaving home to work | POMS | 2.59 [1.00, 4.67] | 0.20 [−0.22, 0.97] | 1.38 [−0.53, 3.51] | −0.03 [−0.61, 0.47] | −2.28 0.415 |

| COVID-19 deaths | CAS | 0.08 [0.00, 0.17] | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.02] | 0.01 [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.10 [0.04, 0.19] | 0.31 0.029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Negri, A.; Conte, F.; Caldiroli, C.L.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Castiglioni, M. Psychological Factors Explaining the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Mental Health: The Role of Meaning, Beliefs, and Perceptions of Vulnerability and Mortality. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020162

Negri A, Conte F, Caldiroli CL, Neimeyer RA, Castiglioni M. Psychological Factors Explaining the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Mental Health: The Role of Meaning, Beliefs, and Perceptions of Vulnerability and Mortality. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(2):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020162

Chicago/Turabian StyleNegri, Attà, Federica Conte, Cristina L. Caldiroli, Robert A. Neimeyer, and Marco Castiglioni. 2023. "Psychological Factors Explaining the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Mental Health: The Role of Meaning, Beliefs, and Perceptions of Vulnerability and Mortality" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 2: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020162

APA StyleNegri, A., Conte, F., Caldiroli, C. L., Neimeyer, R. A., & Castiglioni, M. (2023). Psychological Factors Explaining the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Mental Health: The Role of Meaning, Beliefs, and Perceptions of Vulnerability and Mortality. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020162