The Influence of Victim Self-Disclosure on Bystander Intervention in Cyberbullying

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Impact of Victim Self-Disclosure (Frequency, Valence, and Privacy) on Bystander Intervention

1.2. Victim Blaming as a Mediator

1.3. Interpersonal Distance as a Moderator

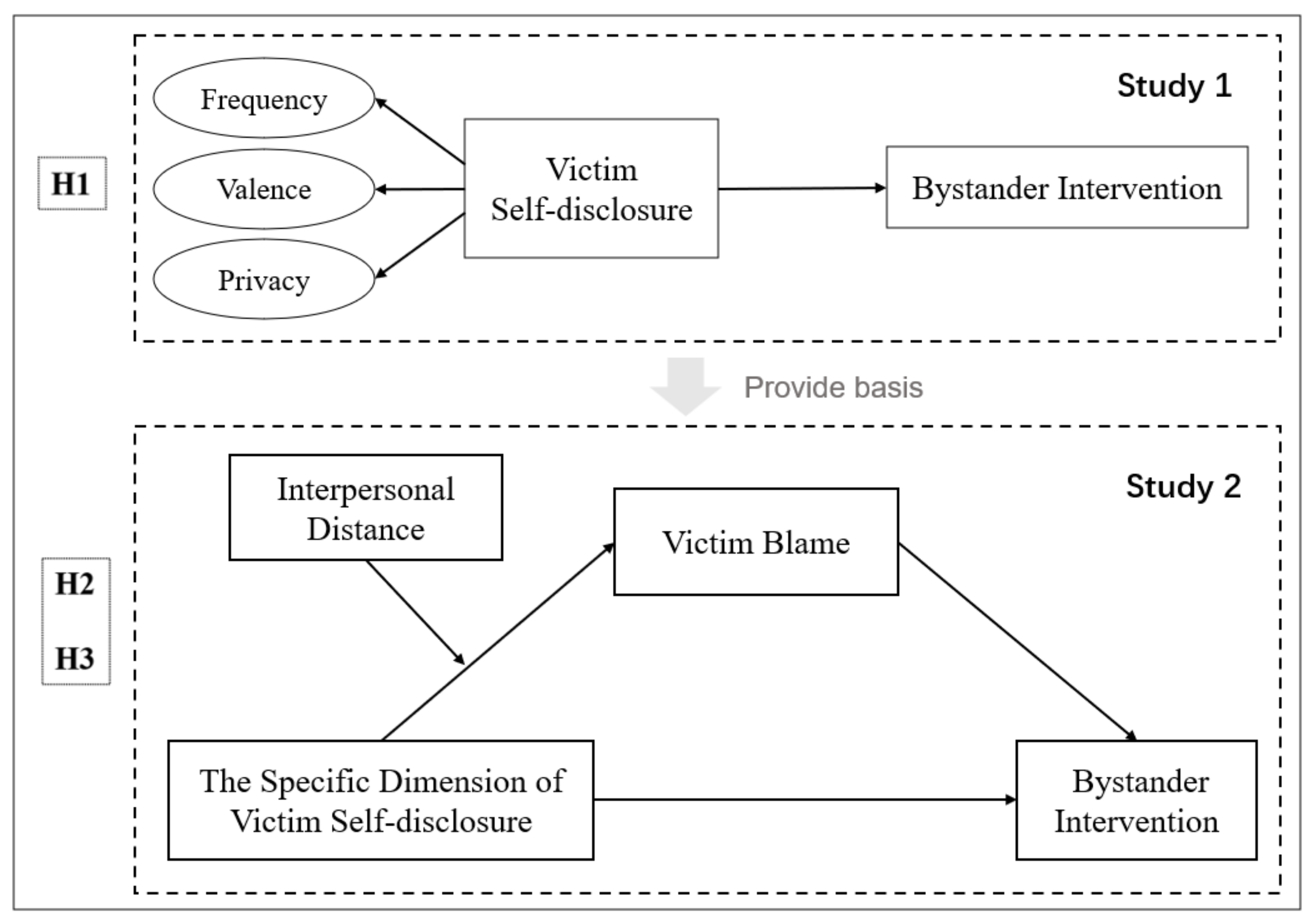

1.4. The Current Study

2. Study 1: The Impact of the Frequency, Valence, and Privacy of Victim Self-Disclosure in Cyberbullying on Bystander Interventions

2.1. Purpose

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Design

2.2.3. Procedure

2.2.4. Materials

Cyberbullying Scenarios

Bystander Intervention

Frequency of Weibo Usage

Agreeableness

Cyberbullying Scenarios Validity Assessment

2.3. Results

2.3.1. Analysis of the Control Variables and Cyberbullying Scenarios

2.3.2. Bystander Intervention

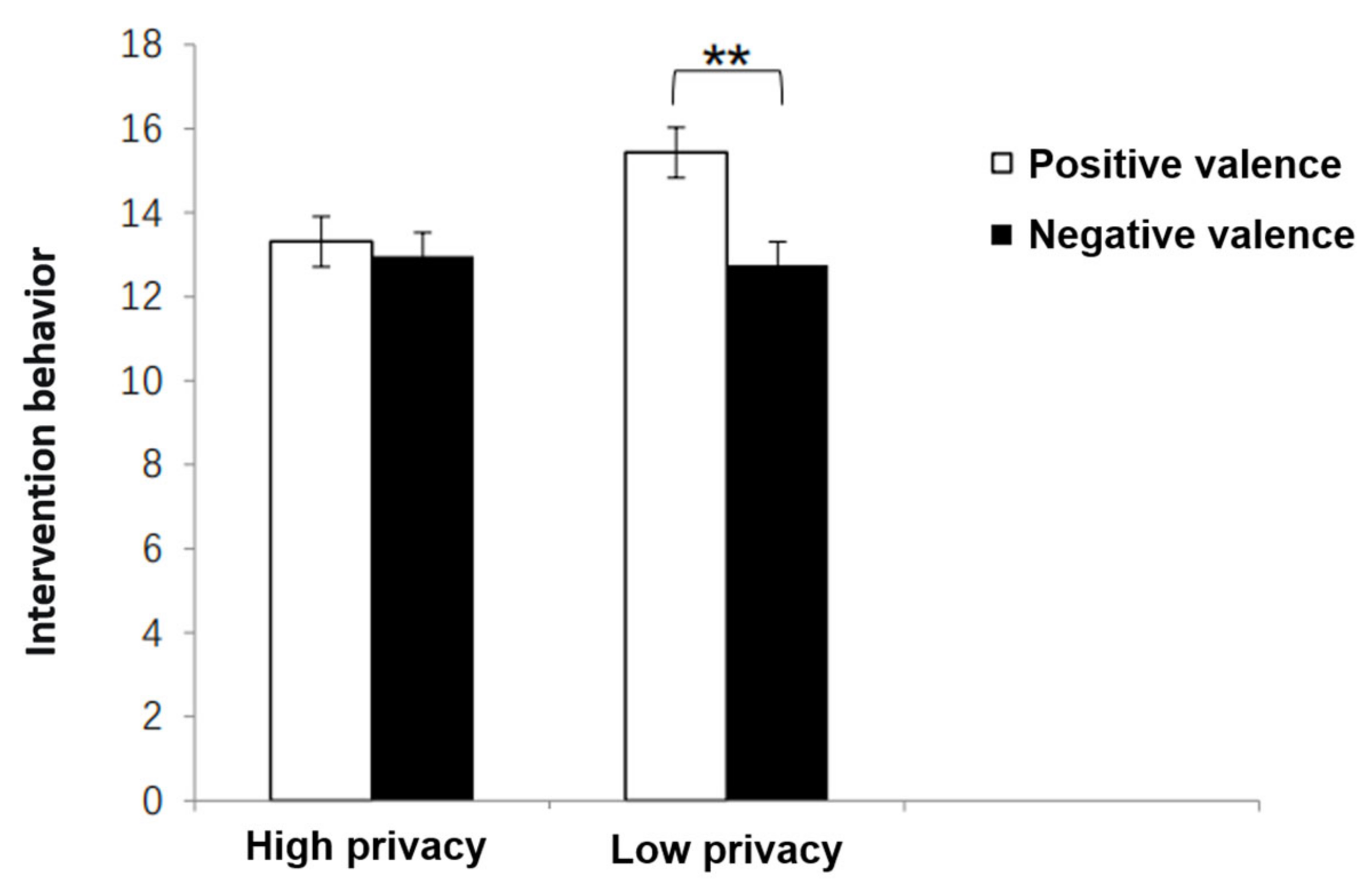

2.4. Discussion

3. Study 2: The Impact of Victim Self-Disclosure Valence on Bystander Intervention and Its Psychological Process

3.1. Purpose

3.2. Method

3.2.1. Participants

3.2.2. Design

3.2.3. Procedure

3.2.4. Materials

Cyberbullying Scenarios

Bystander Intervention

Victim Blaming

Interpersonal Distance

Weibo Usage Frequency and Agreeableness

Self-Efficacy

Cyberbullying Experiences

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

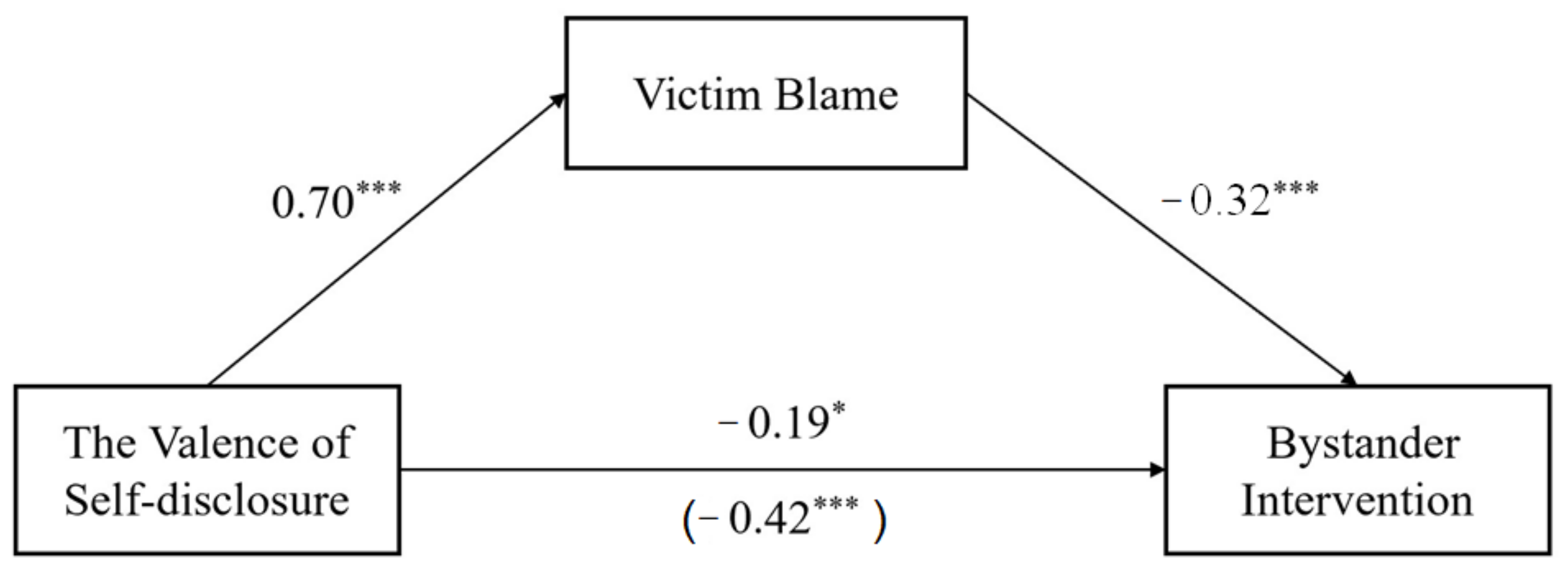

3.3.2. Mediation Effect Analysis

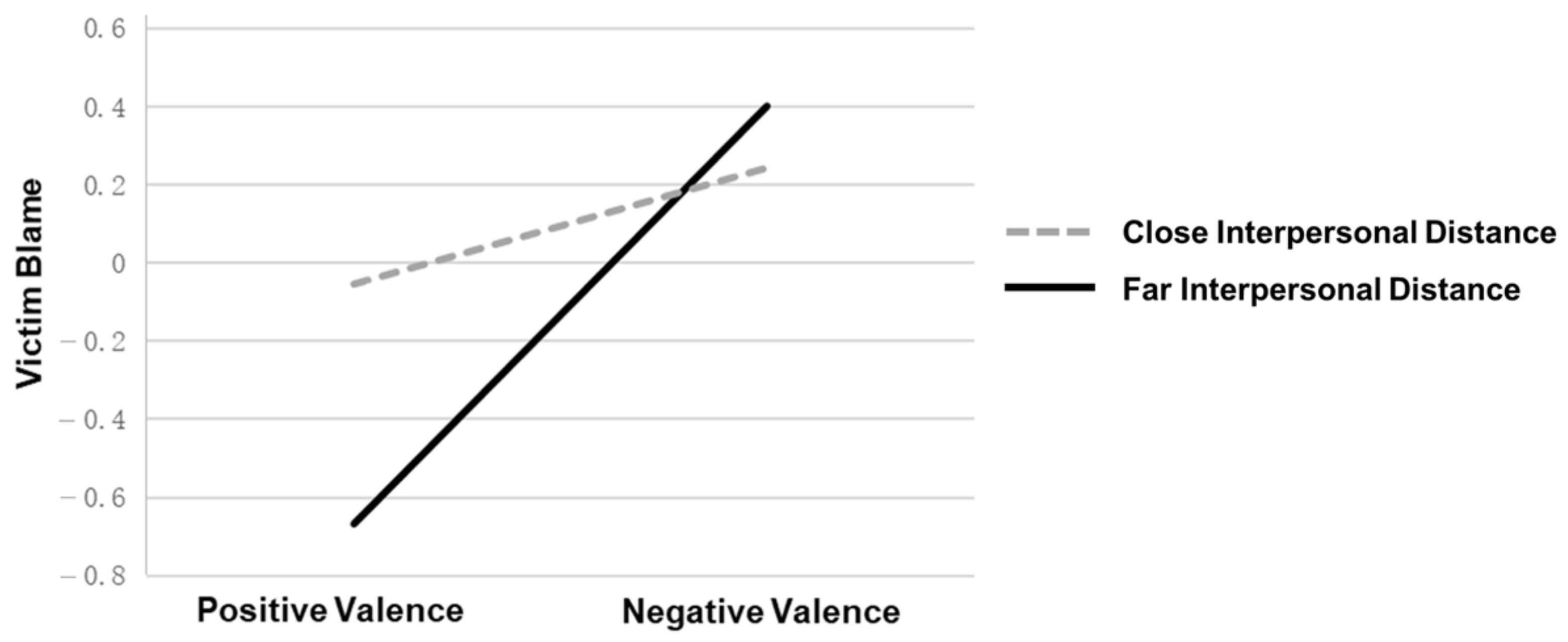

3.3.3. Moderation Effect Analysis

3.4. Discussion

4. General Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Victim’s Self-Disclosure Frequency, Valence, and Privacy on Bystander Intervention

4.2. Psychological Process of Victim Self-Disclosure Valence on Bystander Intervention

4.3. The Application Value of the Study

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P. Electronic bullying among middle school students. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, S22–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Giumetti, G.W.; Schroeder, A.N.; Reese, H.H. Cyberbullying among College Students: Evidence from Multiple Domains of College Life. In Misbehavior Online in Higher Education; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2012; pp. 293–321. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Luo, C.; Lin, Y.; Shadiev, R. Exploring Chinese youth’s Internet usage and cyberbullying behaviors and their relationship. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2018, 27, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, A.; Sulla, F.; Santamato, M.; di Furia, M.; Toto, G.A.; Monacis, L. Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization Prevalence among Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Giumetti, G.W.; Schroeder, A.N.; Lattanner, M.R. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1073–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, L.J.; Allan, A.; Cross, D. Adolescent perceptions of bystanders’ responses to cyberbullying. New Media Soc. 2017, 19, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, R.; Smith, P.K.; Frisén, A. The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. Bystander. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bystander (accessed on 27 September 2018).

- Barlinska, J.; Szuster, A.; Winiewski, M. Cyberbullying among adolescent bystanders: Role of the communication medium, form of violence, and empathy. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 23, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cleemput, K.; Vandebosch, H.; Pabian, S. Personal characteristics and contextual factors that determine “helping,” “joining in,” and “doing nothing” when witnessing cyberbullying. Aggress. Behav. 2014, 40, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahagan, K.; Vaterlaus, J.M.; Frost, L.R. College student cyberbullying on social networking sites: Conceptualization, prevalence, and perceived bystander responsibility. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhao, S.M.; Li, Z. Review and Prospect of the Research on the Impact of Employee Performance on Interpersonal Harmful Behavior. J. Manag. Sci. 2019, 16, 1415–1422. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Holfeld, B. Perceptions and attributions of bystanders to cyber bullying. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Zhang, L.; Kou, Y. The influence of just world belief on the willingness to help among university students: The role of responsibility attribution and helping cost. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2014, 30, 496–503. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Menabò, L.; Skrzypiec, G.; Slee, P.; Guarini, A. What Roles Matter? An Explorative Study on Bullying and Cyberbullying by Using the Eye-Tracker. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, e12604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer, N.C.; Winter, S. Impression management 2.0: The relationship of self-esteem, extraversion, self-efficacy, and self-presentation within social networking sites. J. Media Psychol. 2008, 20, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbaugh, E.E.; Ferris, A.L. Facebook self-disclosure: Examining the role of traits, social cohesion, and motives. Comput. Human Behav. 2014, 30, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z. Types, Functions, and Influencing Factors of Online Self-disclosure. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 21, 272–281. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeless, L.R. A follow-up study of the relationships among trust, disclosure, and interpersonal solidarity. Hum. Commun. Res. 1978, 4, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X. Revision and Impact Mechanism Research of Social Networking Sites Self-Disclosure Questionnaire. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2013. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Schacter, H.L.; Greenberg, S.; Juvonen, J. Who’s to Blame? The Effects of Victim Disclosure on Bystander Reactions to Cyberbullying. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Ziegele, M.; Schnauber, A. Blaming the Victim: The Effects of Extraversion and Information Disclosure on Guilt Attributions in Cyberbullying. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, A.L.; Wood, J.V. When Social Networking Is Not Working: Individuals with Low Self-Esteem Recognize but Do Not Reap the Benefits of Self-Disclosure on Facebook. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chu, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, C. Bystander Behavior in Cyberbullying. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 27, 1248–1257. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, J.B.; Parks, M.R. Cues Filtered Out, Cues Filtered in Computer-Mediated Communication and Relationships. In Handbook of Interpersonal Communication, 3rd ed.; Knapp, M.L., Daly, J.A., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 529–563. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, G.G.; Brodie, Z.P.; Wilson, M.J.; Ivory, L.; Hand, C.J.; Sereno, S.C. Celebrity Abuse on Twitter: The Impact of Tweet Valence, Volume of Abuse, and Dark Triad Personality Factors on Victim Blaming and Perceptions of Severity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 103, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Dang, C. The Impact of Belief in a Just World and Embodied Cognition on Blaming the Victim. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 25, 1377–1383. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Asch, S.E. Forming Impressions of Personality. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1946, 41, 258–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozin, P.; Royzman, E.B. Negativity Bias, Negativity Dominance, and Contagion. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 5, 296–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agger, B. Oversharing: Presentations of Self in the Internet Age; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, A.; Bastiaensens, S.; Cleemput, K.V.; Poels, K.; Vandebosch, H.; Bourdeaudhuij, I.D. Mobilizing Bystanders of Cyberbullying: An Exploratory Study into Behavioural Determinants of Defending the Victim. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2012, 181, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DeSmet, A.; Veldeman, C.; Poels, K.; Bastiaensens, S.; Van Cleemput, K.; Vandebosch, H.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Determinants of Self-Reported Bystander Behavior in Cyberbullying Incidents Among Adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-Level Theory of Psychological Distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, D.; Marques, J.M.; Bown, N.; Henson, M. Pro-Norm and Anti-Norm Deviance within and between Groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U.; Gächter, S. Strong Reciprocity, Human Cooperation, and the Enforcement of Social Norms. Hum. Nat. 2002, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, H.; Spiekermann, S.; Koroleva, K.; Hildebrand, T. Online Social Networks: Why We Disclose. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.M. Tweet This: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective on How Active Twitter Use Gratifies a Need to Connect with Others. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Vitak, J.; Gray, R.; Lampe, C. Cultivating Social Resources on Social Network Sites: Facebook Relationship Maintenance Behaviors and Their Role in Social Capital Processes. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2014, 19, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, A.; Harpaz-Gorodeisky, G.; Ben-David, Y. Defensive Helping: Threat to Group Identity, Ingroup Identification, Status Stability, and Common Group Identity as Determinants of Intergroup Help-Giving. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazerooni, F.; Taylor, S.H.; Bazarova, N.N. Cyberbullying Bystander intervention: The Number of Offenders and Retweeting Predict Likelihood of Helping a Cyberbullying Victim. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2018, 23, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaensens, S.; Vandebosch, H.; Poels, K.; Van Cleemput, K.; DeSmet, A.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Cyberbullying on Social Network Sites. An Experimental Study into Bystanders’ Behavioural Intentions to Help the Victim or Reinforce the Bully. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, P.J.R.; Betts, L.R.; Stiller, J.; Kellezi, B. Bystander responses to cyberbullying: The role of perceived severity, publicity, anonymity, type of cyberbullying, and victim response. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 131, 107238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Schwartz, S.; Capanna, C.; Vecchione, M.; Barbaranelli, C. Personality and politics: Values, traits, and political choice. Polit. Psychol. 2006, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Borgogni, L.; Perugini, M. The “big five questionnaire”: A new questionnaire to assess the five factor model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1993, 15, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wu, D.X.; Zhong, X. Reliability and Validity of Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory among Nurses. China J. Health Psychol. 2013, 21, 1684–1687. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Ding, Q.; Wei, H.; Hong, J. The Impact of Post Subject Characteristics on Knowledge Sharing Behavior in Virtual Communities: The Perspective of the Bystander Effect. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2018, 2, 226–234. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Oh, I. Factors influencing bystanders’ behavioral reactions in cyberbullying situations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zheng, W.; Wei, X.; Lin, W.; Yang, C.; He, Y. The Relationship Between Resilient Personality and Internet Altruistic Behavior: The Mediating Role of Internet Self-Efficacy. J. Hangzhou Norm. Univ. 2016, 15, 461–465. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Bresnahan, M.; Musatics, C. Combating Weight-Based Cyberbullying on Facebook with the Dissenter Effect. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Y. Reliability and Validity Study of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 1, 37–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chu, X.; Fan, C. Revision and Reliability and Validity Test of the Revised Network Bullying Scale in the Group of Chinese Junior High School Students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 25, 1031–1034. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.R.; Kowalski, R.M. Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q. Analysis of the Connotation and Composition of China’s “Positive Energy” Culture. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 233–238. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, K.; Diao, C. The Highest Virtue of a Gentleman, Political Virtue Cultivation and World Peace—An Interpretation of Mencius’s “Benevolence to Others”. Moral. Civiliz. 2020, 3, 54–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, A.D.; Guillory, J.E.; Hancock, J.T. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogut, T. Someone to blame: When identifying a victim decreases helping. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lu, P. Stigmatization and Identity Resistance: A Mechanism Study on the Occurrence of Campus Bullying–Analysis Based on Four Typical Bullying Cases. Chin. Youth Stud. 2021, 1, 46–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, N.; Loughnan, S. Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, E.; McCabe, K.; Smith, V.L. Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 653–660. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L.; Schachter, S.; Back, K. Social Pressures in Informal Groups; A Study of Human Factors in Housing; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Zuo, B.; Wen, F.; Tan, X. The Influence of Group Identity on Inter-Group Sensitivity Effect and Its Behavioral Performance. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2020, 52, 993–1003. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yu, Z. Indigenous Personality Research: The Situation in China. Chin. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 1, 192–222. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. The Game Between “Kin Concealment” and “Righteousness Destroying Kinship”: The Chinese Face of Kin Exemption. Chin. Law. 2014, 6, 89–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Understanding eHealth Literacy from a Privacy Perspective: eHealth Literacy and Digital Privacy Skills in American Disadvantaged Communities. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 1431–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz-Chassidim, H.; Ayalon, O.; Mendel, T.; Hirschprung, R.S.; Toch, E. Selectivity in posting on social networks: The role of privacy concerns, social capital, and technical literacy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.; Seshadri, S. From virtual travelers to real friends: Relationship-building insights from an online travel community. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlińska, J.; Szuster, A.; Winiewski, M. Cyberbullying among adolescent bystanders: Role of affective versus cognitive empathy in increasing prosocial cyberbystander behavior. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, R.S. Following You Home from School: A Critical Review and Synthesis of Research on Cyberbullying Victimization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | M | SD | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Frequency | 23.26 | 3.11 | 0.20 | 0.65 |

| 23.10 | 2.68 | ||||

| Privacy | 23.34 | 2.79 | 0.64 | 0.42 | |

| 23.03 | 3.01 | ||||

| Valence | 23.44 | 2.74 | 2.08 | 0.15 | |

| 22.92 | 3.04 | ||||

| Weibo Usage Frequency | Frequency | 3.25 | 1.26 | 0.59 | 0.45 |

| 3.38 | 1.40 | ||||

| Privacy | 3.25 | 1.33 | 0.56 | 0.46 | |

| 3.37 | 1.34 | ||||

| Valence | 3.28 | 1.41 | 0.14 | 0.71 | |

| 3.35 | 1.25 | ||||

| Agreeableness | Frequency | 36.42 | 15.17 | 0.34 | 0.56 |

| 35.51 | 13.10 | ||||

| Privacy | 36.83 | 14.58 | 0.79 | 0.37 | |

| 35.14 | 13.77 | ||||

| Valence | 35.66 | 14.423 | 0.09 | 0.76 | |

| 36.31 | 13.94 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bystander intervention | 3.13 | 0.83 | — | |||||

| 2. Victim Blaming | 10.92 | 3.68 | −0.37 ** | — | ||||

| 3. Cyberbullying Experience | 18.57 | 6.15 | 0.01 | 0.05 | — | |||

| 4. Frequency of Weibo Usage | 3.94 | 1.34 | 0.14 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.01 | — | ||

| 5. Agreeableness | 34.61 | 13.53 | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.01 | — | |

| 6. Self-efficacy | 34.35 | 5.94 | −0.03 | 0.10 * | −0.10 * | −0.05 | 0.07 | — |

| Effect | Effect Value | Boot SE | LLCI | ULCI | Ratio to Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect | −0.35 | 0.07 | −0.21 | −0.42 | |

| Direct Effect | −0.16 | 0.07 | −0.01 | −0.19 | 45.71% |

| Indirect Effect | −0.19 | 0.03 | −0.26 | −0.13 | 54.29% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, D.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, A.; Qi, K.; Zuo, B.; Liu, X. The Influence of Victim Self-Disclosure on Bystander Intervention in Cyberbullying. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100829

Zeng Y, Xiao J, Li D, Sun J, Zhang Q, Ma A, Qi K, Zuo B, Liu X. The Influence of Victim Self-Disclosure on Bystander Intervention in Cyberbullying. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(10):829. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100829

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Yuze, Junze Xiao, Danfeng Li, Jiaxiu Sun, Qingqi Zhang, Ai Ma, Ke Qi, Bin Zuo, and Xiaoqian Liu. 2023. "The Influence of Victim Self-Disclosure on Bystander Intervention in Cyberbullying" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 10: 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100829

APA StyleZeng, Y., Xiao, J., Li, D., Sun, J., Zhang, Q., Ma, A., Qi, K., Zuo, B., & Liu, X. (2023). The Influence of Victim Self-Disclosure on Bystander Intervention in Cyberbullying. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100829