The Influence of Image Realism of Digital Endorsers on the Purchase Intention of Gift Products for the Elderly

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Endorsers of Products for the Elderly

2.2. The Form Realism of Digital Endorsers

2.3. The Mediating Role of Perceived Social Values

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Advertising Information Framing

3. Materials and Methods

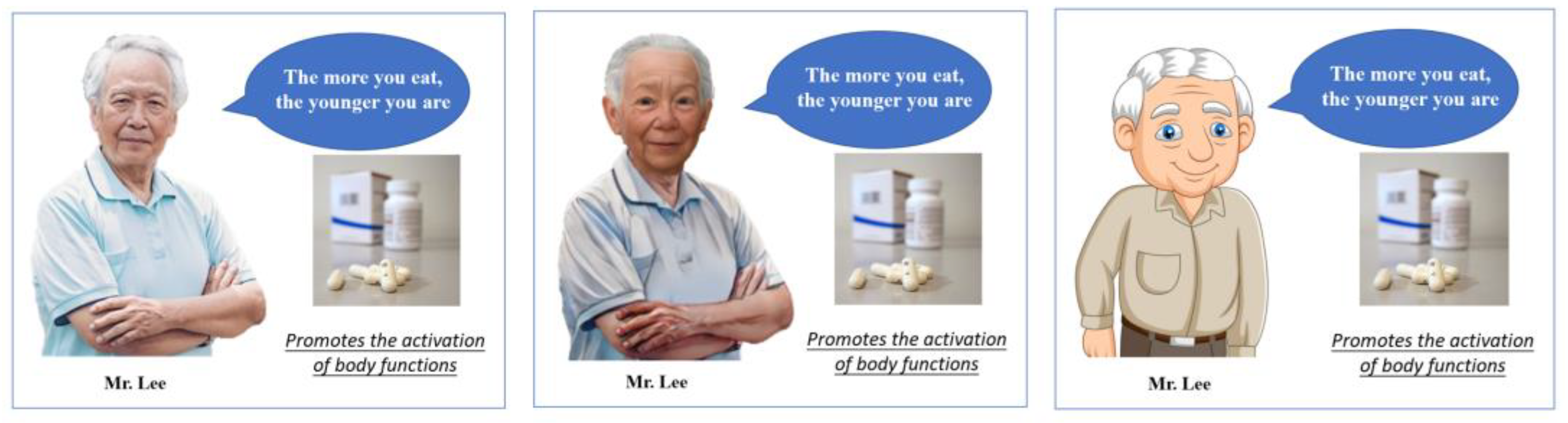

3.1. Design of Stimulus Materials

3.2. Overview of the Studies

4. Study 1

4.1. Participants and Procedures

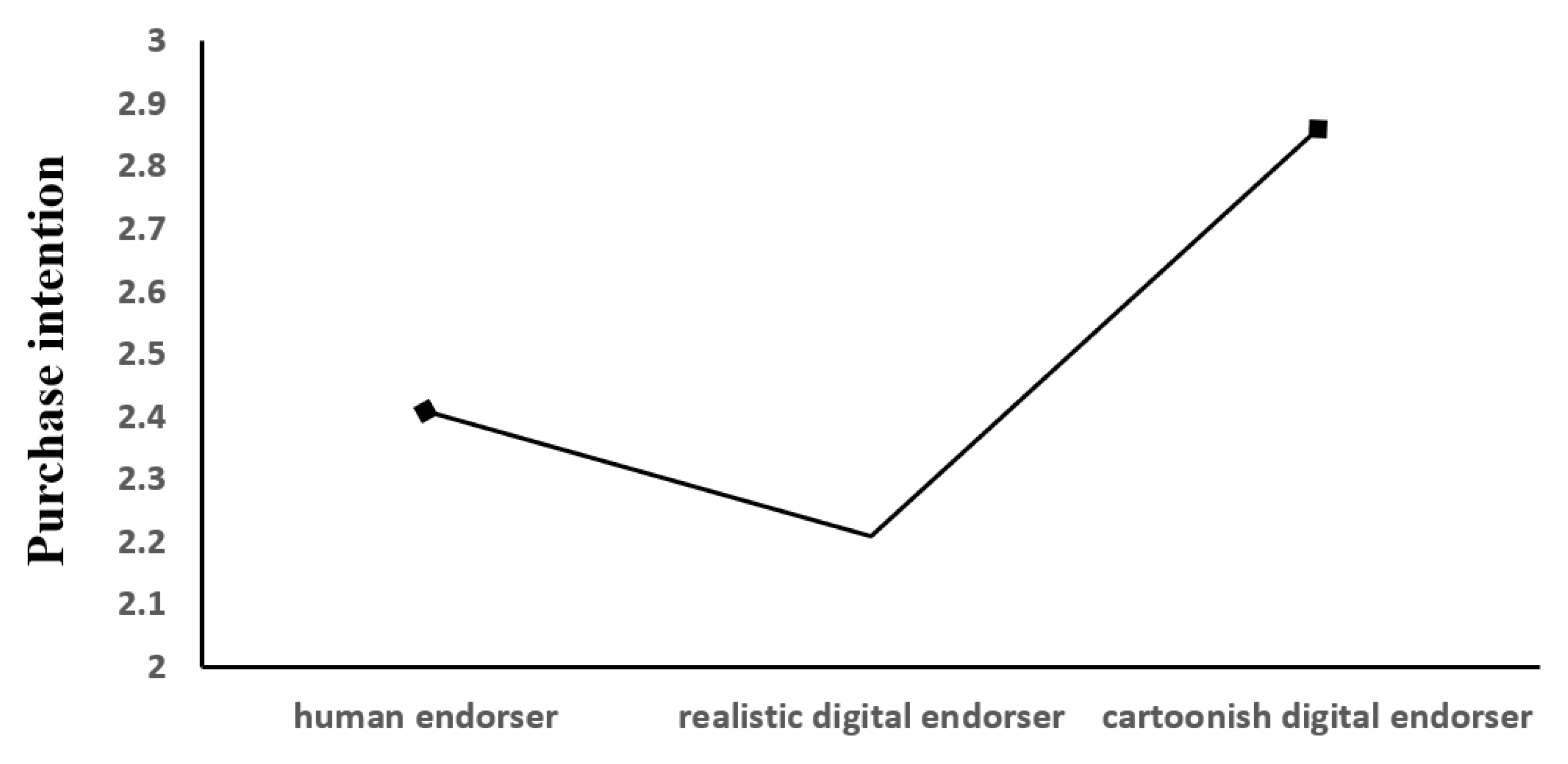

4.2. Results

5. Study 2

5.1. Participants and Procedures

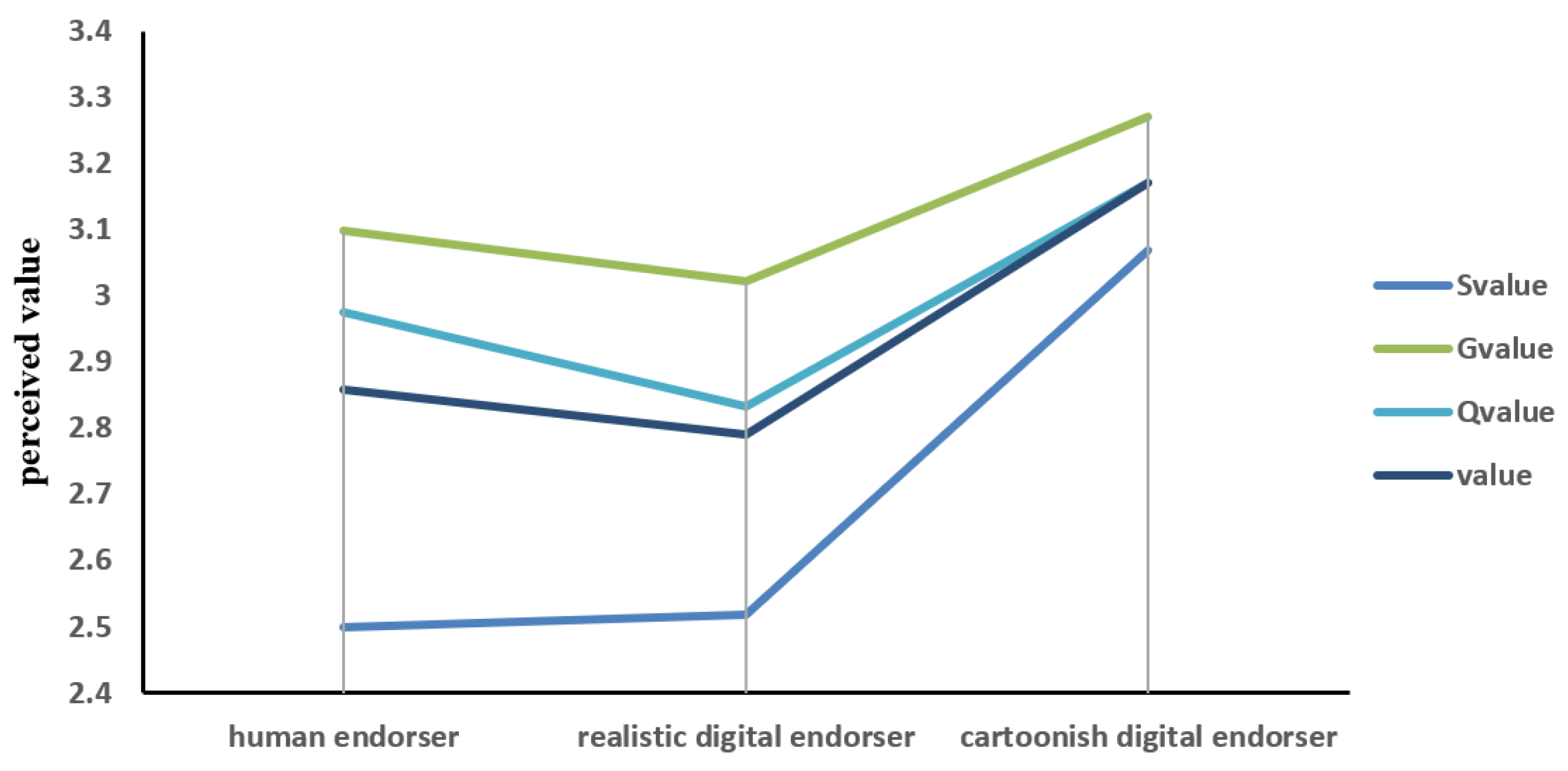

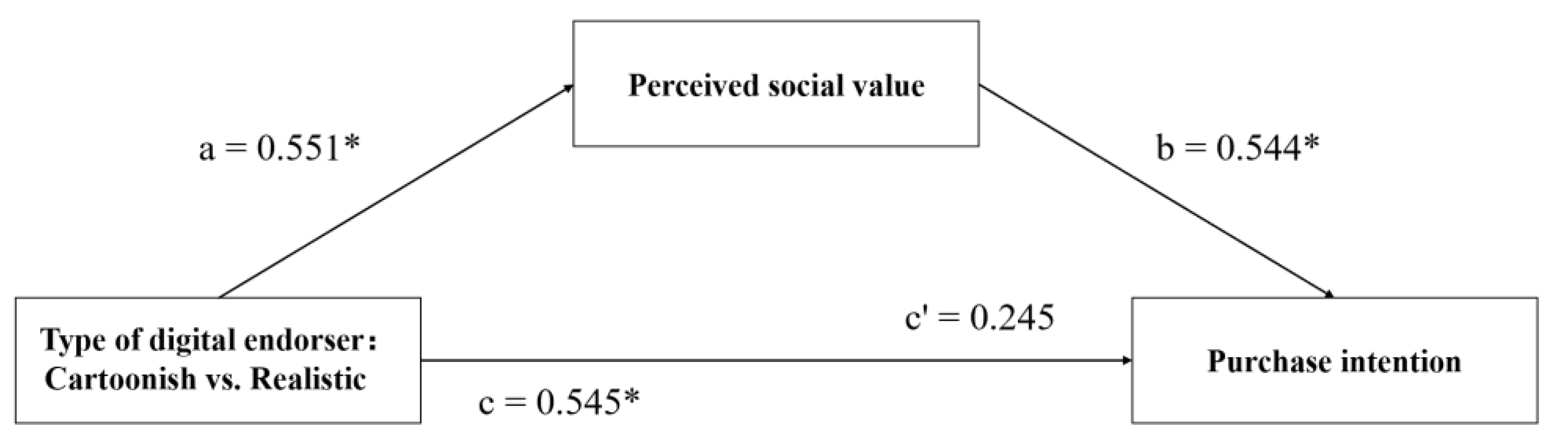

5.2. Results

6. Study 3

6.1. Participants and Procedures

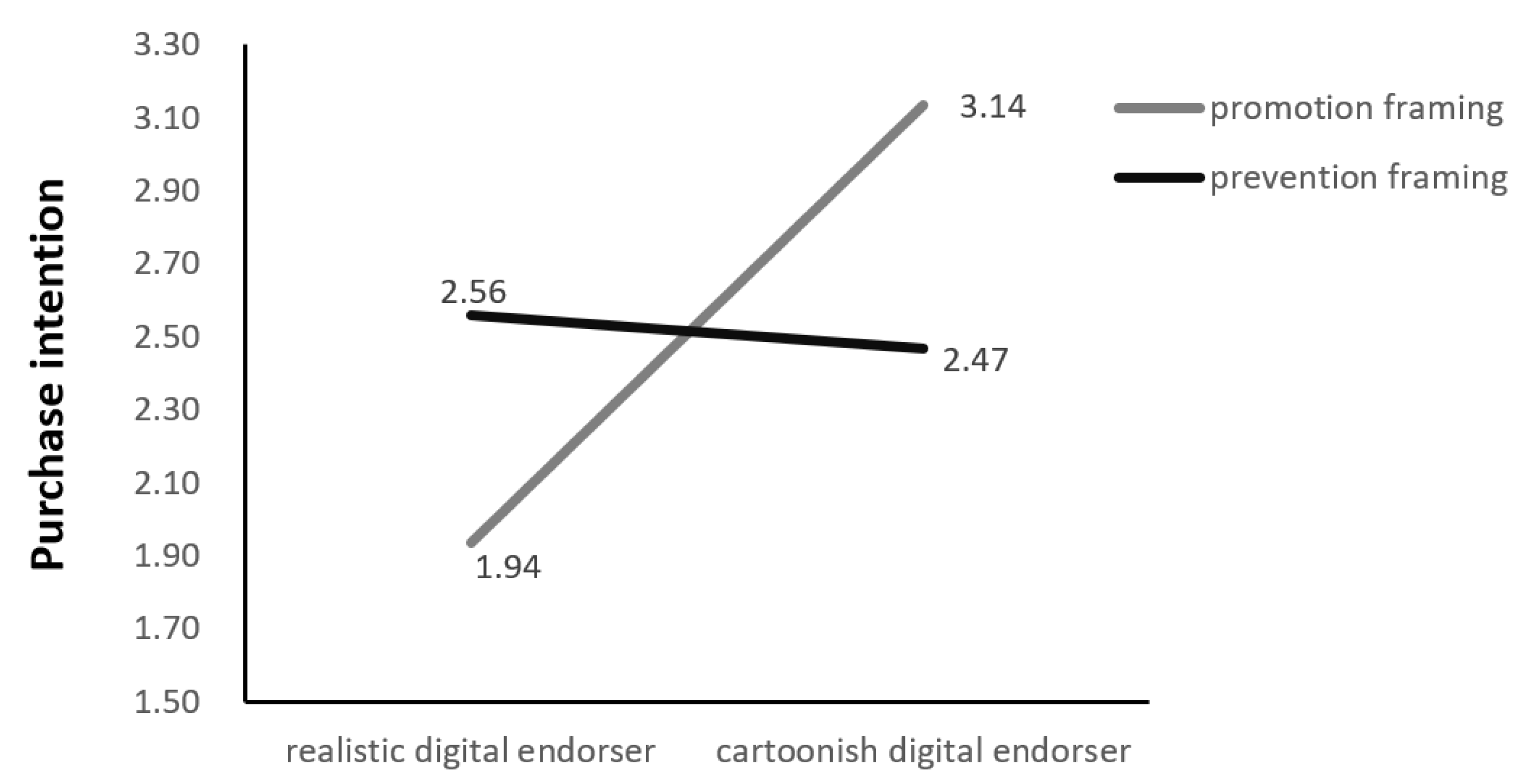

6.2. Results

7. Discussion

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results | Population Division. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/World-Population-Prospects-2022 (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Mazis, M.B.; Ringold, D.J.; Perry, E.S.; Denman, D.W. Perceived Age and Attractiveness of Models in Cigarette Advertisements. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamins, M.A. An Investigation into the “Match-up” Hypothesis in Celebrity Advertising: When Beauty May Be Only Skin Deep. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, F.; Meyer, F.; Vogel, J.; Weihrauch, A.; Hamprecht, J. Endorser Age and Stereotypes: Consequences on Brand Age. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-C.; Peña, J.F.; Drumwright, M.E. Virtual Shopping and Unconscious Persuasion: The Priming Effects of Avatar Age and Consumers’ Age Discrimination on Purchasing and Prosocial Behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.J. Representation of the Elderly in Advertising: Crisis or Inconsequence? J. Serv. Mark. 1988, 2, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D. The Portrayal of Elders in Magazine Cartoons. Gerontol. 1979, 19, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M. Older People in Advertising. J. Advert. 2022, 51, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Banerjee, N. Exploring the Influence of Celebrity Credibility on Brand Attitude, Advertisement Attitude and Purchase Intention. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2018, 19, 1622–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.J.; Chen, J. Nao Bai Jin—The Case Centre. Available online: https://www.thecasecentre.org/products/view?id=64243 (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Black, D. The Virtual Ideal: Virtual Idols, Cute Technology and Unclean Biology. Continuum 2008, 22, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D. The Virtual Idol: Producing and Consuming Digital Femininity. In Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture; Galbraith, P.W., Karlin, J.G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 209–228. ISBN 978-1-349-33445-2. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, J.K.; McLelland, M.A.; Wallace, L.K. Brand Avatars: Impact of Social Interaction on Consumer–Brand Relationships. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 16, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.-A.A.; Bolebruch, J. Avatar-Based Advertising in Second Life. J. Interact. Advert. 2009, 10, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Kim, E.; Choi, S.M.; Sung, Y. Keep the Social in Social Media: The Role of Social Interaction in Avatar-Based Virtual Shopping. J. Interact. Advert. 2013, 13, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ren, J. Virtual Influencers: The Effects of Controlling Entity, Appearance Realism and Product Type on Advertising Effect. In Proceedings of the Design, Operation and Evaluation of Mobile Communications; Salvendy, G., Wei, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 298–305. [Google Scholar]

- Wyer, N.A.; Hollins, T.J.; Pahl, S. The Hows and Whys of Face Processing: Level of Construal Influences the Holistic Processing of Human Faces. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015, 144, 1037–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förster, J.; Liberman, N.; Shapira, O. Preparing for Novel versus Familiar Events: Shifts in Global and Local Processing. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2009, 138, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdim, K.; Belanche, D.; Flavián, M. Attitudes toward Service Robots: Analyses of Explicit and Implicit Attitudes Based on Anthropomorphism and Construal Level Theory. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skågeby, J. Gift-Giving as a Conceptual Framework: Framing Social Behavior in Online Networks. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, I.P.; Schneider, S.L.; Gaeth, G.J. All Frames Are Not Created Equal: A Typology and Critical Analysis of Framing Effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1998, 76, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiken, S. Heuristic versus Systematic Information Processing and the Use of Source versus Message Cues in Persuasion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, B.Z. Celebrity Endorsement: A Literature Review. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. The Impact of Celebrity Spokespersons’ Perceived Image on Consumers’ Intention to Purchase. J. Advert. Res. 1991, 31, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal, B.; Phillips, L.W.; Dholakia, R. The Persuasive Effect of Source Credibility: A Situational Analysis. Public Opin. Q. 1978, 42, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of Brand Personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.M.; La Ferle, C. Does Gender Impact the Perception of Negative Information Related to Celebrity Endorsers? J. Promot. Manag. 2009, 15, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, B.D.; Shimp, T.A. Endorsers in Advertising: The Case of Negative Celebrity Information. J. Advert. 1998, 27, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kim, K.J. Consumer Response to Negative Celebrity Publicity: The Effects of Moral Reasoning Strategies and Fan Identification. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 29, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seno, D.; Lukas, B.A. The Equity Effect of Product Endorsement by Celebrities: A Conceptual Framework from a Co-branding Perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Rifon, N.J. It Is a Match: The Impact of Congruence between Celebrity Image and Consumer Ideal Self on Endorsement Effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. How Does a Celebrity Make Fans Happy? Interaction between Celebrities and Fans in the Social Media Context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Oh, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Choi, S.P.; Wee, J.H. Differences in Youngest-Old, Middle-Old, and Oldest-Old Patients Who Visit the Emergency Department. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2018, 5, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunan, D.; Di Domenico, M. Older Consumers, Digital Marketing, and Public Policy: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Public Policy Mark. 2019, 38, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasi, P.; Vuojärvi, H.; Rivinen, S. Promoting Media Literacy Among Older People: A Systematic Review. Adult Educ. Q. 2021, 71, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouali, W.; Souiden, N. The Role of Cognitive Age in Explaining Mobile Banking Resistance among Elderly People. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursic, A.C.; Ursic, M.L.; Ursic, V.L. A Longitudinal Study of the Use of the Elderly in Magazine Advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Powell, H. Older consumers and celebrity advertising. Ageing Soc. 2012, 32, 1319–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert-Pandraud, R.; Laurent, G.; Lapersonne, E. Repeat Purchasing of New Automobiles by Older Consumers: Empirical Evidence and Interpretations. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, C.; Skufca, L. Media Image Landscape: Age Representation in Online Image. Innov Aging 2020, 4, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, M.; Wernick, A. Images of Aging: Cultural Representations of Later Life; Taylor & Francis US: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-415-11259-8. [Google Scholar]

- Iancu, I.; Iancu, B. Designing Mobile Technology for Elderly. A Theoretical Overview. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 155, 119977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, J.; Marques, S.; Ramos, M.R.; de Vries, H. Internet Use by Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Longitudinal Relationships with Functional Ability, Social Support, and Self-Perceptions of Aging. Psychol. Aging 2021, 36, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Jing, P.; Zhao, Z.; Ding, D. Diet Life Service System and Intelligent Product Design for the Elderly. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Design (ICID), Xi’an, China, 19 October 2021; pp. 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- Prieler, M.; Kohlbacher, F. Advertising in the Aging Society: Setting the Stage. In Advertising in the Aging Society: Understanding Representations, Practitioners, and Consumers in Japan; Prieler, M., Kohlbacher, F., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-1-137-58660-5. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, D.B.; Stevens, E.M.; Noar, S.M.; Widman, L. Public Reactions to and Impact of Celebrity Health Announcements: Understanding the Charlie Sheen Effect. Howard J. Commun. 2019, 30, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nast, C. Despite Push for Age Diversity, Young Models Still Rule the Runway. Available online: https://www.voguebusiness.com/fashion/age-diversity-fashion-weeks-balenciaga (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Benyamini, Y.; Burns, E. Views on Aging: Older Adults’ Self-Perceptions of Age and of Health. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 17, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Gathani, J.; Tricomi, P.P. Virtual Influencers in Online Social Media. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2022, 60, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, M.; Ramadan, Z.; Nasr, L.I. Computer-Generated Influencers: The Rise of Digital Personalities. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2022, 40, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Kozlenkova, I.V.; Wang, H.; Xie, T.; Palmatier, R.W. An Emerging Theory of Avatar Marketing. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.H.; Ahmad, H.; Goraya, M.A.S.; Akram, M.S.; Shafique, M.N. Let’s Play: Me and My AI-Powered Avatar as One Team. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang Barrera, K.; Shah, D. Marketing in the Metaverse: Conceptual Understanding, Framework, and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S.; Giannakis, M.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Dennehy, D.; Metri, B.; Buhalis, D.; Cheung, C.M.K.; et al. Metaverse beyond the Hype: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Emerging Challenges, Opportunities, and Agenda for Research, Practice and Policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, S.J.; Raithel, S. Managing Negative Celebrity Endorser Publicity: How Announcements of Firm (Non)Responses Affect Stock Returns. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 1473–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, H.; Iyer, R.; Sampat, B. Customer Brand Engagement through Chatbots on Bank Websites– Examining the Antecedents and Consequences. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2022, 38, 1212–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Choi, M.; Oh, M.; Kim, S. Service Robots in Hotels: Understanding the Service Quality Perceptions of Human-Robot Interaction. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzwarth, M.; Janiszewski, C.; Neumann, M.M. The Influence of Avatars on Online Consumer Shopping Behavior. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.-A.A. The Roles of Modality Richness and Involvement in Shopping Behavior in 3D Virtual Stores. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 23, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.d.B.; de Farias, S.A.; Grigg, M.K.; Barbosa, M. de L. de A. Online Engagement and the Role of Digital Influencers in Product Endorsement on Instagram. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2020, 19, 133–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, J.; Li, Y. Examining the Effects of Authenticity Fit and Association Fit: A Digital Human Avatar Endorsement Model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito Silva, M.J.; de Oliveira Ramos Delfino, L.; Alves Cerqueira, K.; de Oliveira Campos, P. Avatar Marketing: A Study on the Engagement and Authenticity of Virtual Influencers on Instagram. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2022, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chuenterawong, P.; Lee, H.; Chock, T.M. Anthropomorphism in CSR Endorsement: A Comparative Study on Humanlike vs. Cartoonlike Virtual Influencers’ Climate Change Messaging. J. Promot. Manag. 2022, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.S.; Bonetti, F. Digital Humans in Fashion: Will Consumers Interact? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, P.M. The Role of Baseline Physical Similarity to Humans in Consumer Responses to Anthropomorphic Animal Images. Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, M.; Yuan, L.; Dennis, A.; Riemer, K. Have We Crossed the Uncanny Valley? Understanding Affinity, Trustworthiness, and Preference for Realistic Digital Humans in Immersive Environments. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2021, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Song, S.W.; Chock, T.M. Uncanny Valley Effects on Friendship Decisions in Virtual Social Networking Service. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderberg, C.K.; Callahan, S.P.; Kochersberger, A.O.; Amit, E.; Ledgerwood, A. The Effects of Psychological Distance on Abstraction: Two Meta-Analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, S.; Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Creeping Dispositionism: The Temporal Dynamics of Behavior Prediction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, Y.D.; Carnevale, J.J.; Rosario, M. A Construal Level Approach to Understanding Interpersonal Processes. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass. 2018, 12, e12409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, S.; Uleman, J.S.; Trope, Y. Spontaneous Trait Inference and Construal Level Theory: Psychological Distance Increases Nonconscious Trait Thinking. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, M.; Ambady, N.; Richeson, J.A.; Fujita, K.; Gray, H.M. Stereotype Performance Boosts: The Impact of Self-Relevance and the Manner of Stereotype Activation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, M.; Sen, A. The Tacit Dimension; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Ambady, N.; Bernieri, F.J.; Richeson, J.A. Toward a Histology of Social Behavior: Judgmental Accuracy from Thin Slices of the Behavioral Stream. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 32, 201–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.D.; Dunn, D.S.; Kraft, D.; Lisle, D.J. Introspection, Attitude Change, and Attitude-Behavior Consistency: The Disruptive Effects of Explaining Why We Feel the Way We Do. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 22, 287–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Grand, R.; Mondloch, C.J.; Maurer, D.; Brent, H.P. Early Visual Experience and Face Processing. Nature 2001, 410, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogeeswaran, K.; Dasgupta, N. The Devil Is in the Details: Abstract versus Concrete Construals of Multiculturalism Differentially Impact Intergroup Relations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 106, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.G.; Spreng, R.A. Modelling the Relationship between Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions in a Business-to-business, Services Context: An Empirical Examination. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Measurement and Evaluation of Satisfaction Processes in Retail Settings. J. Retail. 1981, 57, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gounaris, S.P.; Tzempelikos, N.A.; Chatzipanagiotou, K. The Relationships of Customer-Perceived Value, Satisfaction, Loyalty and Behavioral Intentions. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2007, 6, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Monroe, K.B.; Krishnan, R. The Effects of Price-Comparison Advertising on Buyers’ Perceptions of Acquisition Value, Transaction Value, and Behavioral Intentions. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chau, K.Y.; Shen, H.; Duan, X.; Huang, S. The Influence of Tourists’ Perceived Value and Demographic Characteristics on the Homestay Industry: A Study Based on Social Stratification Theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komter, A. Gifts and Social Relations: The Mechanisms of Reciprocity. Int. Sociol. 2007, 22, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, C.P.; Bonney, L.; Herd, K.B. It’s the Thought (and the Effort) That Counts: How Customizing for Others Differs from Customizing for Oneself. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolacci, G.; Straeter, L.M.; de Hooge, I.E. Give Me Your Self: Gifts Are Liked More When They Match the Giver’s Characteristics. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, N.; Keinz, P.; Steger, C.J. Testing the Value of Customization: When Do Customers Really Prefer Products Tailored to Their Preferences? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, R.; Berthon, P. Gift Giving and Social Emotions: Experience as Content: Gift Giving and Social Emotions. J. Public Aff. 2012, 12, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C. Gifts as Economic Signals and Social Symbols. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S180–S214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, J.F.; McGrath, M.A.; Levy, S.J. The Dark Side of the Gift. J. Bus. Res. 1993, 28, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. Soc. Psychol. Intergroup Relat. 1979, 33, 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Joulain, M.; Mullet, E. Estimating the “appropriate” Age for Retirement as a Function of Perceived Occupational Characteristics. Work. Stress 2001, 15, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mimoun, M.S.; Poncin, I.; Garnier, M. Case Study—Embodied Virtual Agents: An Analysis on Reasons for Failure. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2012, 19, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzach, Y.; Karsahi, N. Message Framing and Buying Behavior: A Field Experiment. J. Bus. Res. 1995, 32, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puto, C.P. The Framing of Buying Decisions. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. The Role of Construal Level in Message Effects Research: A Review and Future Directions. Commun. Theory 2019, 29, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimant, E.; van Kleef, G.A.; Shalvi, S. Requiem for a Nudge: Framing Effects in Nudging Honesty. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 172, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-F.; Lin, C.S.; Liu, L.-T. The Effects of Framing Messages and Cause-Related Marketing on Backing Intentions in Reward-Based Crowdfunding. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers-Levy, J.; Maheswaran, D. Exploring Message Framing Outcomes When Systematic, Heuristic, or Both Types of Processing Occur. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyal, T.; Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. Judging near and Distant Virtue and Vice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raue, M.; Streicher, B.; Lermer, E.; Frey, D. How Far Does It Feel? Construal Level and Decisions under Risk. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2015, 4, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Västfjäll, D. Affect, Moral Intuition, and Risk. Psychol. Inq. 2010, 21, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zhang, L.; Xie, G.-X. Message Framing in Green Advertising: The Effect of Construal Level and Consumer Environmental Concern. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.-F.; Wu, C.-S. Debiasing the Framing Effect: The Effect of Warning and Involvement. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 49, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieck, W.; Yates, J.F. Exposition Effects on Decision Making: Choice and Confidence in Choice. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1997, 70, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, P.; Dunford, R. The Influence of Regulatory Focus on Risky Decision-Making. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.K.; Choi, J.; Wakslak, C.J. The Image Realism Effect: The Effect of Unrealistic Product Images in Advertising. J. Advert. 2019, 48, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Li, C.; Filieri, R. The Role of Humor in Management Response to Positive Consumer Reviews. J. Interact. Mark. 2022, 57, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulard, J.G.; Garrity, C.P.; Rice, D.H. What Makes a Human Brand Authentic? Identifying the Antecedents of Celebrity Authenticity. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.L.; Schonger, M.; Wickens, C. OTree—An Open-Source Platform for Laboratory, Online, and Field Experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2016, 9, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambady, N. The Perils of Pondering: Intuition and Thin Slice Judgments. Psychol. Inq. 2010, 21, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engell, A.D.; Haxby, J.V.; Todorov, A. Implicit Trustworthiness Decisions: Automatic Coding of Face Properties in the Human Amygdala. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 1508–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.C.; Maitland, R.A.; Gallagher, C.E. A Case of the “Heeby Jeebies”: An Examination of Intuitive Judgements of “Creepiness". Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Des Sci. Comport. 2017, 49, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.R.; Kukar-Kinney, M. Investigating Discounting of Discounts in an Online Context: The Mediating Effect of Discount Credibility and Moderating Effect of Online Daily Deal Promotions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Barasz, K.; John, L.K. Why Am I Seeing This Ad? The Effect of Ad Transparency on Ad Effectiveness. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 45, 906–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, C.; Bonezzi, A.; Morewedge, C.K. Resistance to Medical Artificial Intelligence. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 629–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, Second Edition: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4625-3466-1. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, A.B.; Cornwell, T.B. Authenticity in Horizontal Marketing Partnerships: A Better Measure of Brand Compatibility. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Fowler, K. Close Encounters of the AI Kind: Use of AI Influencers As Brand Endorsers. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Kim, S.J.; Biocca, F. The Uncanny Valley: No Need for Any Further Judgments When an Avatar Looks Eerie. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 94, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad-Sajadi, R. The Impact of Online Real-Time Interactivity on Patronage Intention: The Use of Avatars. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Effect (X → Svalue → PI) | B | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect of X on Y | 0.25 | 0.19 | −0.14 | 0.63 |

| Indirect effect of X on Y | 0.29 * | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.59 |

| Total effect of X on Y | 0.54 * | 0.23 | 0.08 | 1.01 |

| Perceived Social Value | Purchase Intention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | |

| X (cartoonish vs. realistic) | −1.277 * | −1.681 | −1.661 * | −3.124 |

| Perceived social value | 0.466 ** | 7.390 | ||

| information framing (promotion vs. prevention) | −1.326 | −1.082 | −2.302 * | −2.957 |

| X×information framing | 0.456 | 0.953 | 0.982 * | 2.957 |

| Age | −0.021 | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.112 |

| Gender | −0.487 * | −1.945 | −0.540 * | −3.082 |

| R2 | 0.108 | 0.684 | ||

| F | 2.892 * | 17.453 ** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Qiu, X. The Influence of Image Realism of Digital Endorsers on the Purchase Intention of Gift Products for the Elderly. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010074

Wang X, Qiu X. The Influence of Image Realism of Digital Endorsers on the Purchase Intention of Gift Products for the Elderly. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaoyi, and Xingyi Qiu. 2023. "The Influence of Image Realism of Digital Endorsers on the Purchase Intention of Gift Products for the Elderly" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010074

APA StyleWang, X., & Qiu, X. (2023). The Influence of Image Realism of Digital Endorsers on the Purchase Intention of Gift Products for the Elderly. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010074