A Secure Base for Entrepreneurship: Attachment Orientations and Entrepreneurial Tendencies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Entrepreneurial Personality

1.2. Attachment Theory

1.3. Entrepreneurial Tendencies and Attachment

1.4. Conceptual Framework: Entrepreneurship as the Ultimate Capacity to Be Alone

1.5. The Current Research

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

2.2. Results and Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.2. Results and Discussion

4. Study 3

4.1. Method

4.2. Results and Discussion

5. General Discussion

Conclusions and Implication

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sánchez, J.C. The impact of an entrepreneurship education program on entrepreneurial competencies and intention. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F. Introduction to Entrepreneurship; South-Western: La Jolla, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 2–30. [Google Scholar]

- Maaravi, Y.; Heller, B.; Amar, S.; Stav, H. Training techniques for entrepreneurial value creation. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 3, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.; Rubinstein, Y. Smart and illicit: Who becomes an entrepreneur, and do they earn more? Q. J. Econ. 2017, 132, 963–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E. The big five personality dimensions and entrepreneurial status: A meta-analytical review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, J.M.; Ainuddin, R.A.; Junit, S.O.H. Effects of self-concept traits and entrepreneurial orientation on firm performance. Int. Small Bus. J. 2006, 24, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.J.; Casteleiro, C.M.L.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Guerra, M.D. Entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurship in European countries. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 10, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A metanalysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, C.; Burns, J. The measurement of locus of control: Assessing more than meets the eye? J. Psychol. 2000, 134, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Shook, C.L.; Ireland, R.D. The concept of “opportunity” in entrepreneurship research: Past accomplishments and future challenges. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus, R.H., Sr. Risk-taking propensity of entrepreneurs. Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, Volume 1: Attachment, 2nd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Schoon, I.; Duckworth, K. Who becomes an entrepreneur? Early life experiences as predictors of entrepreneurship. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, L.; Marshall, T. Anxious attachment and relationship processes: An interactionist perspective. J. Personal. 2011, 79, 1219–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, Volume 2: Separation: Anxiety and Anger; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S.N. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Psychology Press: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory; Routledge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley, R.C.; Shaver, P.R. Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2000, 4, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, K.A.; Clark, C.L.; Shaver, P.R. Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships; Simpson, J.A., Rholes, W.S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 25, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, K.; Grossmann, K.E.; Kindler, H. Early care and the roots of attachment and partnership representations: The Bielefeld and Regensburg longitudinal studies. In Attachment from Infancy to Adulthood: The Major Longitudinal Studies; Grossmann, K.E., Grossmann, K., Waters, E., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 98–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2003; Volume 35, pp. 53–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Boosting attachment security to promote mental health, prosocial values, and inter-group tolerance. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillath, O.; Karantzas, G. Attachment security priming: A systematic review. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 25, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.D.; Campbell, W.K. Attachment and exploration in adults: Chronic and contextual accessibility. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnelley, K.B.; Ruscher, J.B. Adult attachment and exploratory behavior in leisure. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2000, 15, 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M. Adult attachment style and information processing: Individual differences in curiosity and cognitive closure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green-Hennessy, S.; Reis, H.T. Openness in processing social information among attachment types. Pers. Relatsh. 1998, 5, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, R. Toward measurement of entrepreneurial tendencies. Manag. Int. Rev. 1980, 20, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zelekha, Y.; Yaakobi, E.; Avnimelech, G. Attachment orientations and entrepreneurship. J. Evol. Econ. 2018, 28, 495–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caird, S. General Measure of Enterprising Tendency Test. 2013. Available online: www.get2test.net (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Neustadt, E.; Chamorro-Premuzic, T.; Furnham, A. The relationship between personality traits, self-esteem, and attachment at work. J. Individ. Differ. 2006, 27, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.S.; Simpson, J.A.; Griskevicius, V.; Huelsnitz, C.O.; Fleck, C. Childhood attachment and adult personality: A life history perspective. Self Identity 2019, 18, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R.; Rom, E. The effects of implicit and explicit security priming on creative problem solving. Cogn. Emot. 2011, 25, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R.; Gal, I. An attachment perspective on solitude and loneliness. In The Handbook of Solitude: Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation, Social Withdrawal, and Being Alone, 2nd ed.; Coplan, R.J., Bowker, J.C., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Maritz, A. Networking, entrepreneurship, and productivity in universities. Innovation 2010, 12, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Stephan, U. Advancing the psychology of entrepreneurship: A review of the psychological literature and an introduction. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 65, 437–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.A. A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual-Opportunity Nexus; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Caird, S.P. A Review of Methods of Measuring Enterprise Attributes; University of Durham Business School: Durham, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, K.; Grossmann, K.E.; Kindler, H.; Zimmermann, P. A wider view of attachment and exploration. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, 2nd ed.; Cassidy, J., Shaver, P.R., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 857–879. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D.W. The capacity to be alone. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1958, 39, 416–420. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, M. On the development of mental functioning. Int. J. Psycho-Anal. 1958, 39, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P.; Honig, B. The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, A.; Peake, W.O.; Stewart, W.; Watson, W.E. Emotional intelligence, interpersonal process effectiveness, and entrepreneurial performance. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2014, 1, 15816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, J.; Muegge, S. Venture capital’s role in innovation: Issues, research, and stakeholder interests. In International Handbook on Innovation; Shavinina, L.V., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 641–663. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Florian, V. The relationship between adult attachment styles and emotional and cognitive reactions to stressful events. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships; Simpson, J.A., Rholes, W.S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R.; Gillath, O.; Nitzberg, R.A. Attachment, caregiving, and altruism: Boosting attachment security increases compassion and helping. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 817–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

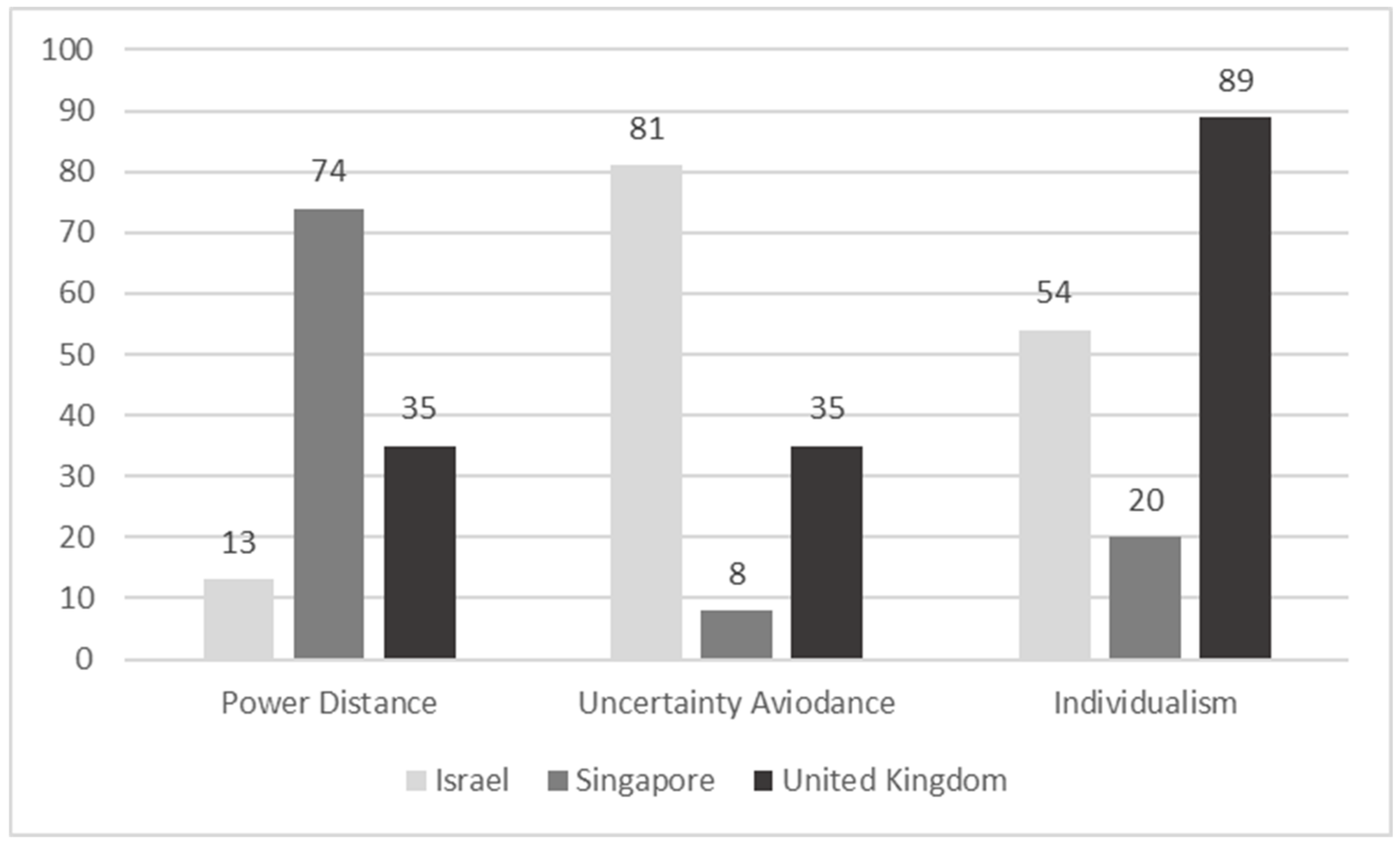

- Antoncic, J.A.; Antoncic, B.; Gantar, M.; Hisrich, R.D.; Marks, L.J.; Bachkirov, A.A.; Li, Z.; Polzin, P.; Borges, J.L.; Coelho, A.; et al. Risk-taking propensity and entrepreneurship: The role of power distance. J. Enterprising Cult. 2018, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swierczek, F.W.; Ha, T.T. Entrepreneurial orientation, uncertainty avoidance, and firm performance: An analysis of Thai and Vietnamese SMEs. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2003, 4, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Sagi-Schwartz, A. Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: Universal and contextual dimensions. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, 2nd ed.; Cassidy, J., Shaver, P.R., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 880–905. [Google Scholar]

- Genome, S. Global Startup Ecosystem Report 2021; Startup Genome: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, C.H.; Villareal, M.J. Individualism-collectivism and psychological needs: Their relationships in two cultures. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1989, 20, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D. So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? In Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 329–356. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M.; Russell, D.W.; Zakalik, R.A. Adult attachment, social self-efficacy, self-disclosure, loneliness, and subsequent depression for freshman college students: A longitudinal study. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboal, D.; Veneri, F. Entrepreneurs in Latin America. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 46, 503–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Israel | Singapore | United Kingdom | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment orientation ⇨ Entrepreneurial tendencies ⇩ | Anxiety | Avoidance | Anxiety | Avoidance | Anxiety | Avoidance |

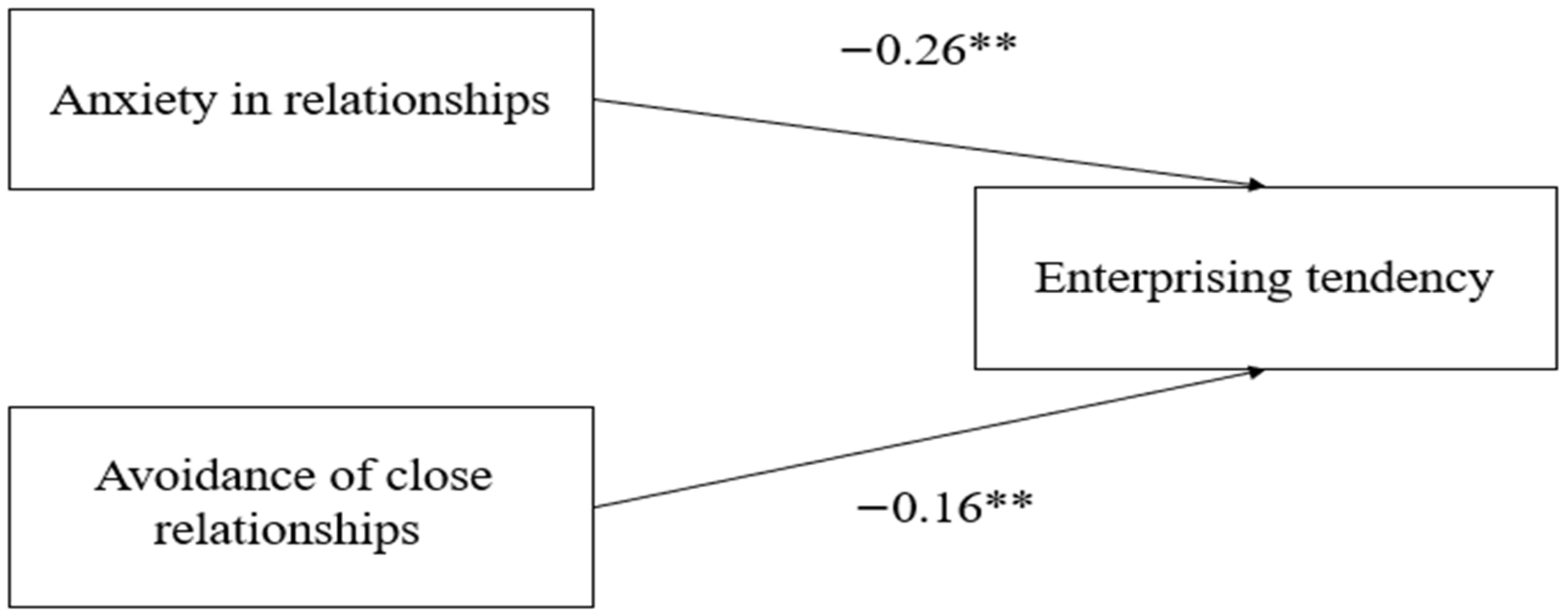

| Enterprising Tendency | β = −0.26 *** | β = −0.16 ** | β = −0.16 *** | β = −0.18 *** | β = −0.14 * | ns |

| Calculated Risk−Taking | β = −0.18 ** | β = −0.19 ** | ns | β = −0.27 *** | β = −0.16 * | ns |

| Locus of Control | β = −0.26 *** | β = −0.2 *** | β = −0.23 *** | β = −0.1 * | β = −0.13 * | β = −0.10 ns |

| Need for achievement | β = −0.2 *** | ns | β = −0.16 ** | ns | ns | ns |

| Creative Tendency | β = −0.11 ns | ns | ns | β = −0.15 ** | ns | ns |

| Need for Autonomy | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Segal, S.; Mikulincer, M.; Hershkovitz, L.; Meir, Y.; Nagar, T.; Maaravi, Y. A Secure Base for Entrepreneurship: Attachment Orientations and Entrepreneurial Tendencies. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010061

Segal S, Mikulincer M, Hershkovitz L, Meir Y, Nagar T, Maaravi Y. A Secure Base for Entrepreneurship: Attachment Orientations and Entrepreneurial Tendencies. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleSegal, Sandra, Mario Mikulincer, Lihi Hershkovitz, Yuval Meir, Tamir Nagar, and Yossi Maaravi. 2023. "A Secure Base for Entrepreneurship: Attachment Orientations and Entrepreneurial Tendencies" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010061

APA StyleSegal, S., Mikulincer, M., Hershkovitz, L., Meir, Y., Nagar, T., & Maaravi, Y. (2023). A Secure Base for Entrepreneurship: Attachment Orientations and Entrepreneurial Tendencies. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010061